When I worked in eldercare, both in assisted living facilities and in a nursing home, people who found out I was a novelist would often say things like, “Lots of material around here,” or “Do you write about your work?” I would always smile wryly and say no, my writing is pretty much unrelated.

I write epic fantasy. My characters swing swords, cast spells, and alternately wield or try to evade divine intervention. With a single memorable exception, they do not have dementia or even act particularly irrationally. Most of the time, the connection between my writing and my work wasn’t nearly as obvious as people apparently imagined.

But there is a connection. Writing fantasy helped me build a particular set of problem-solving skills that I used in my work day in and day out. To explain how, I’m going to have to tell you a bit about best practices in dementia care.

First off, dementia is an umbrella term. It does not describe a single disease or disorder, but a set of symptoms that could have any number of causes. In that sense, I have always thought of it as similar to pneumonia: pneumonia just means that your lungs are full of something and therefore less effective. Whether that something is fluid resulting from a bacterial infection, a virus, a near-drowning, or the aspiration of food and drink, the symptoms and dangers are similar enough that we use the same term to describe them.

Similarly, dementia-like symptoms can be caused by all sorts of things: dehydration, lack of sleep, chronic stress, interaction with certain medications, traumatic brain injury, stroke, long-term effects from alcoholism or other chemical addictions, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and many lesser-known and less common causes and manifestations. You’ll notice, though, that this list can be separated into reversible causes of delirium, like dehydration or chronic stress, and irreversible ones like Alzheimer’s disease (it’s generally only the irreversible causes that are classified as dementia, for all that the symptoms can be identical). To date, we have no cure for Alzheimer’s, let alone Parkinson’s, Lewy Body, Huntington’s, Korsakoff syndrome (the form often related to alcoholism), or vascular dementia. In eldercare, these are the dementias we work with day to day.

So how do we manage an incurable disease? With humanity. We recognize that these are progressive, degenerative diseases, and that a person whose brain is shrinking and dying will not be able to inhabit our reality for long.

That’s not a metaphor; I’m not talking about mortality. I mean that our shared understanding of how the world works, how space and time function, is a world apart from what a dementia patient can understand and relate to. The idea that winter is cold, or that one does not leave the house naked (especially at that time of year!), or that a person born in 1920 cannot possibly be just four years old in 2018 – none of these are necessarily obvious to a person with middle- or late-stage dementia. As a result, our usual instinct to insist that winter is too cold to go outside naked, that a person born in 1920 must be nearly a hundred years old by now, becomes intensely counterproductive. What we might think of as “pulling them back to reality,” a person with dementia experiences as gaslighting. When we insist on impossible things, all we can accomplish is to piss somebody off.

Or worse. I once worked with a woman whose daughter visited nearly every day, and every time she asked where her husband was, the response was, “Dad died, mom. Two years ago.”

It was the first time she had heard that devastating news.

Every time.

In dementia care, we try to teach people not to do that. Your insistence on a certain reality cannot force people to join you there and be “normal” again. There are no magic words that will cure a degenerative brain disease.

What we do instead is to join people in their realities. If you’re a centenarian and you tell me your mother is coming to pick you up from school soon, I might ask you what you feel like doing when you get home. Play cards? Why, I have a deck right here! We can play while we wait for her!

And that’s where the connection to writing fantasy comes in, because an in-world problem must always have an in-world solution. Just as my characters won’t be treating their prophetic visions with Zyprexa or Seroquel, you can’t soothe a person who’s hallucinating or paranoid by telling them they’re wrong about everything.

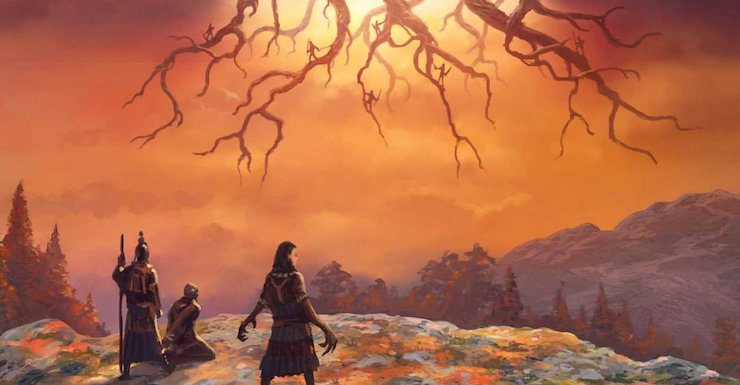

Buy the Book

A Breach in the Heavens

I worked once with a lady whose father had been a minister, whose husband had been a minister, who responded to stress by raining fire and brimstone upon the unbelievers. She told me that one of our nurses, Eric, was trying to steal God but that God would crush him under His foot. Oh sure, he was laughing now, and he’d laugh and laugh and laugh all the way to the Bad Place. She yelled at everybody who wasn’t taking Eric to jail that they would be sorry, and of course when other residents yelled at her to shut up, the trouble only escalated.

Medicines are useless in such a context: nobody could have gotten this lady to take anything when she was having a fire-and-brimstone moment.

But in-world problems have in-world solutions.

I told her I believed her. I told her we should leave Eric to his fate and get away from him, God-thief that he was. I walked her back to her room and listened for half an hour or more while she poured her heart out, telling me, in some combination of English and word salad, about the evil that had befallen her. I just sat there and listened, nodding, validating, letting her feel heard, until she had gotten it—whatever it was—off her chest. Then we walked back together and she sat across from Eric once more, newly calm and magnanimous.

Most of us will deal with dementia at some point in our lives, if we haven’t already. It’s a scary place to be sometimes, and a wondrous place. I’ve seen music transform someone completely. I’ve been told that Jesus was standing right behind me.

When you do find yourself in fantasyland, remember: it’s easier to sell love potions than medicine.

N.S. Dolkart is the author of the Godserfs trilogy: Silent Hall, Among the Fallen, and A Breach in the Heavens, which is out now from Angry Robot Books. He spent eight years working in eldercare, six of them at a skilled nursing facility, directed a memory care unit, and has trained front-line staff in dementia care best practices. He is now a very happy stay-at-home dad.