In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

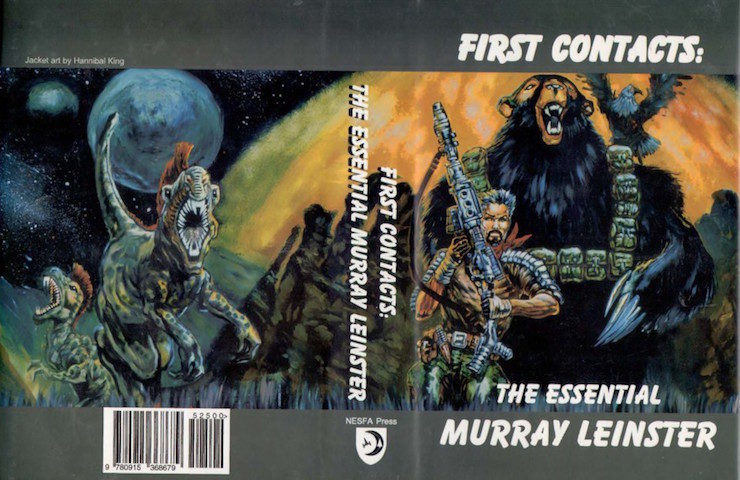

When I was a youngster reading my dad’s Analog back issues in the mid-1960s, there were many authors I enjoyed, including H. Beam Piper, Mack Reynolds, and Poul Anderson. Among them was an author named Murray Leinster, whose stories always felt fresh, always had an aspect that made you think, and often had a rather ironic or humorous view of the human condition. What I didn’t know was that this author had begun his writing career just after the First World War, back in the days before the genre was even popularly known as “science fiction.” It was a pleasure for me to take a trip down memory lane through the pages of one of those lovingly assembled anthologies from NESFA Press, First Contacts: The Essential Murray Leinster.

When you ask people today about famous science fiction authors, Murray Leinster probably wouldn’t be one of the first names you would hear mentioned. Even during his lifetime, while Leinster was always well respected by his peers, he was often overshadowed by more widely read authors. But this is also the author who coined the term “first contact,” wrote one of the first and most influential alternate history stories, and who in 1946 wrote a story that did an uncanny job of predicting how the Internet would work. When you look at the length of his career, the fact that it included good stories during every phase, and at the breadth and novelty of his ideas, you can easily come to the conclusion that Leinster deserves wider recognition. So, let’s take a look at this remarkable man, and just a sampling from a remarkable career…

About the Author

Murray Leinster was the most commonly used pen name of William Fitzgerald Jenkins (1896-1975), an early pioneer in the new genre of science fiction, and a prolific writer of all varieties of pulp and mainstream fiction—including adventure, westerns, mysteries, horror, and even romance—in addition to non-fiction. He also wrote movie, TV, and radio scripts. During the course of his prolific career, he wrote well over a thousand shorter works, and dozens of novels and collections.

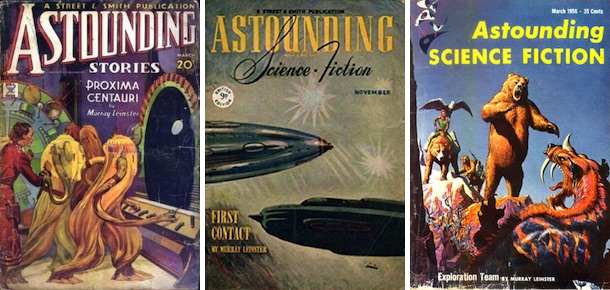

Leinster’s first published fiction appeared in 1916, and his first science fiction tale, “Runaway Skyscraper,” a story of a building moving backwards in time, appeared in Argosy magazine in 1919. He was a longtime contributor to Astounding/Analog, with his work appearing steadily from the very first issue onward; other science fiction magazines he contributed to included Amazing Stories, Galaxy Science Fiction, and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. His stories in other genres appeared in host of pulps: Argosy, Black Mask, Breezy Stories, Cowboy Stories, Danger Trails, Detective Fiction Weekly, Love Story Magazine, Mystery Stories, Snappy Stories, Smashing Western, Weird Tales and West. His work was also published in more prestigious magazines like The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s Weekly, and Esquire. Later in his career, Leinster found work in another new genre, the media tie-in novel, and wrote two novels set in the universe of the Time Tunnel TV show, and three novels in the world of another series, Land of the Giants. Interestingly, film rights to his own novel Time Tunnel had been purchased by 20th Century Fox, and the TV series was inspired by that work.

Because of family financial problems, Leinster had to leave school far earlier than he wanted to, and he never had a chance to attend high school or college. He had wanted to study chemistry, and possessed a keen, logical mind—something quite evident in his stories. He was also a life-long inventor, and under his own name, Will Jenkins, he developed a front projection system that was used in movie special effects shots to make characters appear before a pre-filmed background. He served his country during wartime; in WWI, he worked for the Committee on Public Information and served in the U.S. Army, and during WWII he worked for the United States Office of War Information (OWI).

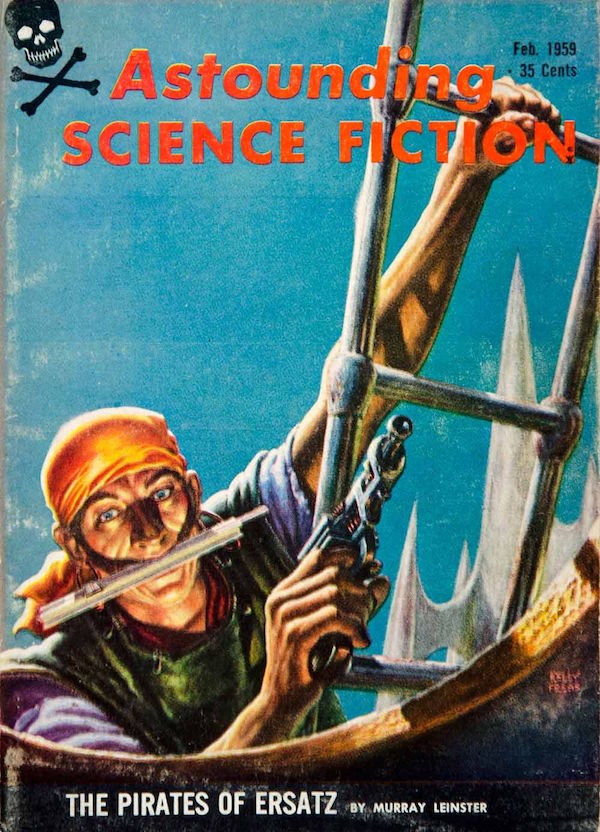

Leinster won a Best Novelette Hugo in 1956 for “Exploration Team,” and was a nominee for the Best Novel Hugo in 1960 for The Pirates of Zan, aka The Pirates of Ersatz. And in recognition of his pioneering efforts in writing alternate history and parallel world stories, The Sidewise Award for Alternate History takes its name from his story “Sidewise in Time.”

By all accounts I could find, Leinster had a reputation as a gentleman, and was kind and generous to his peers, fans and younger writers. As with many authors who were writing in the early 20th Century, the copyrights for a number of works by Leinster have expired, and they can be found online at Project Gutenberg.

First Contacts: The Essential Murray Leinster

This book, a collection from NESFA Press edited by Joe Rico, opens with an appreciation from fellow author Harry Stubbs (aka Hal Clement), who approaches the task from a fan’s perspective. Because there are so many stories included in the volume, I will give most only a short mention here, in order to give readers a sense of the scope and versatility of Leinster’s imagination. I will focus more attention on those tales that I enjoyed the most, or those with particular significance to the science fiction genre.

The first story, “A Logic Named Joe,” written in 1946, does an impressive job of predicting aspects of what we now call the Internet. Leinster calls what we now know as personal computers “logics,” and what we call servers are referred to as “tanks.” When a logic in someone’s home gains sentience and starts overriding censorship measures on the network, all manner of chaos ensues until a technician tracks down the offending unit, and removes it from the net. The fact that our current internet operates without any such censorship will not be lost on the reader. Like many of Leinster’s stories, this one employs an “ordinary guy” vernacular which has not aged well, unfortunately.

The story “If You Was a Moklin” examines humanity’s encounter with a race of mimics, with disturbing results. In “The Ethical Equations,” a junior officer finds a novel solution to the dilemmas posed during a first contact situation. The story “Keyhole” follows researchers as they try to communicate with a being living on the moon, and find it has learned more from them than they’ve learned from it. “Doomsday Deferred” describes a creepy encounter in South America with ants who have developed sentience.

The story “First Contact,” which appeared in Astounding in 1945, has had a profound impact on many science fiction stories that followed, not least in coining the term “first contact.” It thoughtfully describes how ships from two races encounter each other while examining the Crab Nebula, learning each other’s languages with a device we would now call a “universal translator.” Neither race wants to trust the other with the location of their homeworld, as they both think the weaker race’s civilization will inevitably be destroyed. This pessimistic viewpoint is unfortunately firmly rooted in the various encounters between cultures throughout human history. The ways in which the crews learn to respect each other, develop friendships, and find a solution to their problem makes for an interesting and thought-provoking tale.

The story “Nobody Saw the Ship” has a malevolent alien landing on Earth, finding its inhabitants to be an ideal food for his race, only to be defeated by the forces of nature itself. “Pipeline to Pluto” follows unscrupulous criminals putting stowaways on supply ships to Pluto, who end up being hoisted by their own petard. “The Lonely Planet” is somewhat expository in nature, but gives us the unique concept of a planet that is a single gigantic, living organism, and shows how poorly mankind might treat such a marvel. “De Profundis” describes explorers encountering a race of intelligent deep-sea monsters from the monster’s alien perspective. In “The Power,” a medieval alchemist comes across an alien visitor with mysterious powers, and through his ignorance ends up “killing the goose that laid the golden eggs.” In another tale with a pessimistic view of alien encounters, the main characters of “The Castaway” find an alien visitor stranded on Earth, and decide that they must kill the visitor to save the planet from alien domination. “The Strange Case of John Kingman” gives us the story of a mysteriously long-lived man in an asylum whose doctors may be his worst enemy.

“Proxima Centauri” is a longer work, an early story about a generation ship that will take centuries to reach its destination, but encounters malevolent aliens during the journey—aliens desperate for new food sources, who would strip Earth of every living thing. Two men who love the same woman clash as they battle the aliens, and only one will survive the conflict. The story is pulpy and old-fashioned, but also brimming with interesting ideas.

The hero of “The Fourth-Dimensional Demonstrator” finds that he has inherited a machine from his uncle that can use a form of time travel to duplicate any item. He uses it to make some quick cash, only to realize that using bills with duplicate serial numbers is not a good idea. And when his greedy girlfriend accidently duplicates herself, he finds his problems multiplying wildly out of control. In another time travel tale, “Sam, This Is You,” the eponymous Sam, a telephone lineman, receives a call from his future self. Chaos again ensues, but in the midst of the mayhem, Leinster neatly deals with the paradoxes and loops time travel would create.

Both of these time travel tales are simply a warmup for the masterful “Sidewise in Time,” which appeared in Astounding in 1934 and is one of the earliest parallel world stories ever written. The brilliant but creepy Professor Minott finds indications that regions from parallel worlds, where history took a different course, will begin to appear around the world. He decides to find a less advanced timeline and establish himself as a king, using his advanced scientific knowledge. Without explaining his aims, he assembles some of his most capable students—including a female student who he intends to make his queen. They encounter areas in which the Confederacy survived the Civil War, and where the Americas were colonized by Asians. The professor soon finds that his leadership abilities are not as impressive to others as they are to himself, that his intended queen has no intention of reciprocating his affections, and that a Roman-colonized America is not nearly as malleable to his influence as he’d expected. The story is a gripping one, and well told; it is easy to see how it inspired an entire science fiction sub-genre.

“Scrimshaw” is the tale of an old hermit living on the moon’s dark side who finds a creative way to get revenge on a criminal. “Symbiosis” is a clever tale where a small nation finds an unusual medical solution that helps to foil an invasion by an aggressive neighbor—it’s a fun and well-written example of short fiction at its best. In “Cure for a Ylith,” the protagonist uses a mind-reading device and a knowledge of psychology to overthrow a tyrant.

“Plague on Kryder II” is a story from Leinster’s “Med Service” series, which included some of his best work. These stories feature Doctor Calhoun and his alien companion, a “tormal” called Murgatroyd. It turns out that the plague in this story has been created by criminals as a way to extort colony worlds. Calhoun has his hands full figuring this out, and the stakes are raised by the fact this plague can kill even the normally immune tormals. The story is witty and full of twists and turns.

The collection’s finest gem is the story “Exploration Team,” a Hugo winner and one of my all-time favorite tales. Because of a communications error, a Survey officer, Bordman, lands at an illegal exploration outpost. There he finds a single human, Huyghens, aided only by a family of genetically engineered bears and a trained eagle who wears a television camera and functions as a living drone. Huyghens and his team have found a way to survive attacks by the sphexes, vicious lizard-like carnivorous beasts. They find that the authorized colony on the planet, which was using robots to try to establish their outpost, has been overrun by the sphexes. Despite the fact that Huyghens faces prison because of his illegal presence on the planet, he puts his personal interests aside and takes Bordman on an expedition to rescue survivors. The tale does a great job portraying the danger posed by the sphexes, the fascinating abilities of the human/animal team, and the growing respect the men have for each other as they overcome the many challenges they face. Upon re-reading it, however, I couldn’t help but speculate on the level of ecological damage their war on the sphexes would cause.

The collection also contains two previously unpublished stories. The first, “The Great Catastrophe,” was apparently not published due to disagreements with the magazine to which it had been submitted, and is an often expository but well-realized story of a gigantic meteor destroying civilization. A plucky American who has invented a new type of airship finds himself opposing European autocrats whose military might survived in a fleet of submarines—as you can imagine, it will be the plucky American for the win. The second tale, “To All Fat Policemen,” is not science fiction, but looks at the American spirit by comparing two immigrants and how they are treated. Given the political issues we’re currently grappling with in this country and the wider world, the story is as meaningful today as it was when it was written.

Missed Opportunities

One problem with assembling a Best Of anthology covering a long career is that a lot of work will be left out, and you’re bound to miss someone’s favorite. One thing I often wish for in anthologies like this is the inclusion of the original cover art and interior illustrations that appeared with the stories. Even though the tale was not included in this volume, it was a serialized Leinster novel, The Pirates of Ersatz, which inspired one my favorite science fiction cover illustrations: a Kelly Freas cover for Analog that shows a pirate climbing a spaceship’s accommodation ladder with a slide rule clenched in his teeth instead of the usual dagger.

A personal favorite story missing from the collection is Leinster’s “The Other World,” which originally appeared in Startling Stories in 1949 (and I have to thank long-time follower of this column SchuylerH for helping to track this one down). I am pretty sure I first encountered it in one of those Groff Conklin anthologies, 6 Great Short Novels of Science Fiction, found at the local library in the mid-1960s, and it also appears in the collection Robert Adams’ Book of Alternate Worlds. The story follows the adventures of a young archaeologist who finds an ancient Egyptian mirror with strange properties which allows him to see into a parallel world. A scientist friend of the protagonist builds a larger version, and they find they now have a gateway allowing them to travel between the worlds. They discover that the parallel world is inhabited by a parasitic society of slavers descended from ancient Egyptians, aided by intelligent wolf creatures. When our young hero’s girlfriend is kidnapped, all sorts of exciting adventures ensue in a story pitched perfectly to my twelve-year-old heart.

Final Thoughts

If you’ve never heard of Murray Leinster, I strongly suggest you seek out his work. This anthology is a good place to start, and Baen Books has also put out some anthologies of his best stories. And any excuse to visit your local used bookstore is a good one. You don’t even need to leave your couch, though, as some of Leinster’s work that has gone out of copyright is available on the internet at Project Gutenberg.

And now I turn the floor over to you: What are your thoughts on the stories contained in this anthology, and on Leinster’s place in the pantheon of classic science fiction authors? And since I’ve mentioned a favorite tale that wasn’t in the anthology, I encourage you to do the same—what are your favorite Leinster tales that haven’t been mentioned?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.