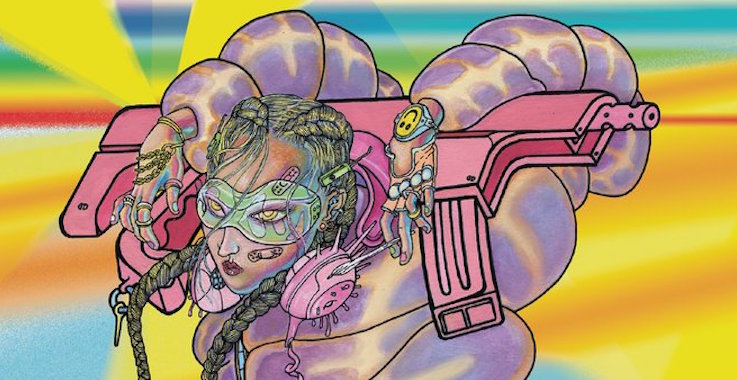

Sometimes a narrative begins in a familiar place: with someone embarking on a journey, for instance. Nikhil Singh’s novel Taty Went West is like that—the first sentence of the second chapter seems to usher the reader into familiar territory. “The piggy bank bought her a bus ticket to nowhere fast,” Singh writes, tapping into a longstanding tradition of young people venturing out into parts unknown. (As if to make this more explicit, Singh includes a nod to the Beat Generation later in the novel.) Taty is a young woman frustrated by suburban life, tuned in to her favorite songs on her Walkman. She’s in search of something bigger, a larger and more compelling world. This is a familiar story, right?

It’s not a familiar story. That bus ticket’s bought in the second chapter. The one before that sets up an altogether stranger milieu, and one that hints at the bizarre scenarios to come.

“There had always been stories of lost cities in the jungle. Descriptions of vast structures hidden behind impenetrable veils of steaming foliage, their once-great plazas and floating pyramids now the haunt of monkeys, shades, and folkloric spiders.”

Buy the Book

Taty Went West

What happens when you take someone familiar and place them in an utterly alien setting? Taty Went West is, in its own way, a series of variations on that theme of contrasts: the known world meeting the impossible world; the transcendental colliding with the sordid; the speculative meeting the delirious. In Taty Went West, a robot can evoke the divine, and a monstrous presence can be the agent of liberation. This is a novel that abounds with contradictions, taking them to absurd ends.

Although the milieu of Singh’s novel could roughly be described as psychedelic science fiction (complete with nods in the direction of William Burroughs and the Grateful Dead), that doesn’t quite get at its fundamental strangeness. Much of the novel finds Taty attempting to deal with some sort of perilous situation, at times facing horrific danger, and grappling with betrayals, violence, and horror around her. After leaving home, she is kidnapped by a mysterious group led by Alphonse Guava, “the imp pimp,” who tells her that she has considerable psychic abilities, able to transmit certain feelings, emotions, and sensations to the people around her.

What transpires from there, more or less, is Taty’s quest for her own freedom. Complicating matters is the presence of bizarre alien symbiotes, whose presence slowly transforms their hosts into something inhuman, a process that can only be staved off by the consumption of an absurdly large number of carrots. If this seems like Cronenbergian body horror by way of Eugene Ionesco, you’re not wrong. It’s par for the course here: that adorable creature you encounter on a given page might be what it seems to be; it also might be something immensely powerful and twice as malicious. That’s the kind of book this is.

The contrasts continue. Most of the characters have names that come off as overly stylized, the stuff of fables or children’s stories: Dr. Dali, Number Nun, Miss Muppet, and Bronski Glass all come to mind. But this is also a novel in which the threat of violence (particularly sexual violence) is present for many of the characters. (In a 2016 conversation with Geoff Ryman, Singh discussed this aspect of the novel.) The cumulative result is jarring—cartoonish one moment, harrowingly visceral the next. But that juxtaposition has been in place from the outset: this may be a novel with ancient cities, mysterious beings, and adventure—but escapism it is not.

Outside of writing, Singh’s body of work includes forays into film, music, and illustration—specifically, a comics adaptation of a novel by the similarly hard-to-define Kojo Laing. That same multifaceted approach can be seen in a distilled form within this novel, both literally (through both illustrations and cues for music in the prose) and metaphorically. Singh has endeavored to combine theoretically incompatible strands of literature: the picaresque blended with New Wave science fiction blended with absurdist comedy blended with realistic looks at trauma and its aftereffects. Does it all neatly flow together? No, but the risks that Singh takes here succeed more often than not, and the result is a deeply singular and highly compelling literary debut.

Taty Went West is available from Rosarium Publishing.

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).