Is there anyone more earnest than a punk? In all the universe the only people who feel things more than punks are, maybe, kids in love for the first time. John Cameron Mitchell’s adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s short story “How to Talk to Girls at Parties” understands this, and squeezes every drop of heartfelt, un-ironic, anguished emotion by combining these two forces into a movie about a young punk’s first love. In Mitchell’s hands, this eerie short story is transformed into a weird, day-glo, feminist, queer-as-hell movie that only he could have made.

This film is not for everyone, but if you love it, you’ll really love it.

John Cameron Mitchell’s three previous films cover a ton of ground: Hedwig and the Angry Inch is America’s greatest cult musical, Shortbus is an incredibly raw and moving exploration of sex and love, and Rabbit Hole is a bleak chronicle of grief. How to Talk to Girls at Parties is Mitchell’s first time adapting someone else’s story, and it’s interesting to see where he takes the basic concept.

Very small plot synopsis: Enn (short for Henry) spends his time running around Croydon hitting punk shows with his two friends John and Vic. They write and illustrate a zine together, and he’s created a character called Vyris Boy, who stands up to fascists and infects people with Enn’s own anti-capitalist ethos. One night they go to their usual punk club, a very small basement space run by Queen Boadicea, a manager who mentored Johnny Rotten and Vivienne Westwood, and other punk greats, only to watch them sell out and head to London. (She’s a little bit bitter.) After that night’s show they go to what they think is an afterparty with the sole, mind-destroying plan of finally getting laid. (Hence the title, and this is almost where the similarity to Gaiman’s short story ends. They end up at the wrong party, accidentally infiltrating a gathering of aliens, one of whom welcomes them in. Here is where we take leave of Gaiman completely.

Where, in the story, the aliens are an unknowable threat, here they are six groups of different types of aliens. Each group is communal, wear themed and color-coded outfits, and seem to share experience in a sort of hivemind. They’ve come to Earth as tourists, to observe life here, and maybe experience a little bit of life as a human. They have 48 hours before they have to leave, and very strict rules about how much life they’re allowed to try out.

These rules get broken. A lot.

One group of aliens just wants to have a variety of different types of sex with as many different genders as they can find. One group participates in a constant free-floating dance party. One group seems to hate all the other groups for having too much fun. And one group chants their devotion to individuality in unison. It’s a member of this group, Zan, who meets Enn, instantly likes him, and says, “take me to the punk.”

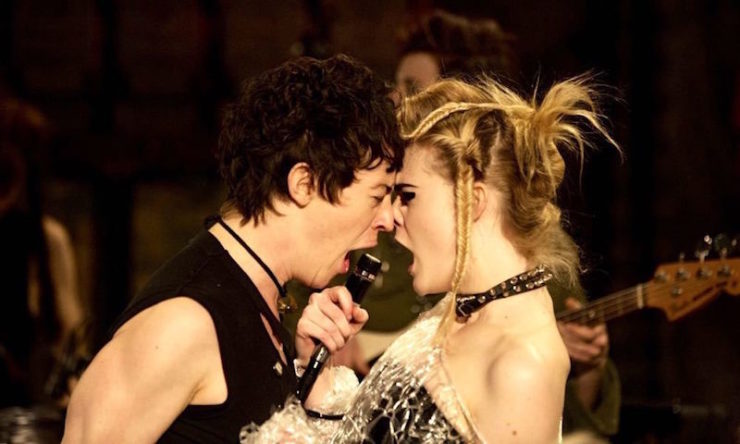

I don’t want to say too much more about the plot, but that 48-hour time limit is ticking away, the prissy aliens are not happy that Zan ran off, and, Enn is falling deeper in love every second, so I’m sure you can imagine how it goes? And the plot stuff isn’t even that important. The performances are all great. Nicole Kidman’s accent is hilarious, Elle Fanning is winning as Zan, Alex Sharp makes you see why an alien would fall in love at first sight with a human, and all the background punks and limber aliens help create a kaleidoscopic, authentic world.

The music is great. Mitchell couldn’t get rights to bigger songs by the Sex Pistols or the New York Dolls so instead he pulled a Velvet Goldmine and created a new group, called the Dyschords, who do original songs and are a home grown Croydon-based punk group. It makes sense that the kids would obsess over a local group, and obviously the road of rock history is paved with the LPs of bands who never “made it,” so it ducks around the rights issues in a realistic way. Same goes for Queen Boadicea—she’s a woman behind the scenes, creating looks, offering advice, and never getting enough credit or the big break that will take her to London. Again, this is realistic—there were plenty of women in punk and New Wave who never got the spotlight the boys did. Much like Velvet Goldmine, the movie uses the aliens as a jolt of innovation on the arts and music scene. Their music, a sort of pulsing Krautrock (created for the film by electronica duo Matmos), attracts the punks and influences a vein of New Wave into their lives.

Mitchell also makes a point of showing pudgy punks, queer punks, sexually fluid punks, and Rastas, who are all part of the larger movement, all treated with respect and love. Is this an act of alt history? Sure. Mitchell is giving us the punk movement as it should have been: anti-fascist, anti-racist, inclusive, queer-friendly, open to girls who want to slam dance and boys who like boys. There were plenty of pockets of the punk movement that were exactly like that, at least for a while, and I think choosing to celebrate them is a great way to point to an arts movement that could be, rather than dwelling on the one that was.

The look of the film is amazing. The candy-colored aliens are like something out of A Clockwork Orange (I have a lot of issues with A Clockwork Orange, but the film’s aesthetic is not among them) or Blow Up, and they contrast beautifully with dingy working-class Croydon… but that isn’t the point. The point is finding the beauty in dingy, working-class Croydon, accepting the town for what it is, rather than wanting it to be London. Seeing beauty in leather and spikes and scuffed-up bikes and smeared make up. The point is rejecting perfection.

This isn’t to say that there are no flaws here—lacking the music of punk’s heaviest hitters, Mitchell instead plasters every bedroom wall with posters, to a degree that made me wonder how Enn was either buying or stealing so many. (Compare with Bev’s room in It, with her two precious posters: one Siouxie Sioux and one Cure, which felt so real and told us so much about her.) The characters also talk about bands maybe a little too knowledgeably? Would a trio of Croydon teens know The New York Dolls, for instance, who were only just getting big on the Lower East Side in 1977? But then again I was so pleased the Dolls got a shout out I kind of didn’t mind…

There is also a musical scene that can either be read as a swipe at Across the Universe, or as an utterly heartfelt ode to love and transcendence that is a little over-the-top even for me… but again, I was happy to accept the movie as it was, even when it got a bit silly. I’ll also say that while the movie captures the tone of Gaiman’s story it doesn’t resemble it beyond that, but I’m honestly glad Mitchell took a horror story and turned it into this yearning scruffy movie.

Now about that fluidity. This movie makes space for two arcs that complicate the essentially hetero tale of first love at its center. One concerns a character gradually realizing their bisexuality, which would be interesting on its own, but is also complicated with questions of consent. There is also a point where a character comes out as asexual, which is a little dodgier, but it also gives us a striking moment of difference in a film that is saturated with different types and expressions of physical affection. And yeah, I’m talking about sex a lot, because this is the director who made freaking Shortbus, and he has never danced around desire.

The film’s other theme, also absent form the story, is the idea of the older generations feeding on the younger. This comes up in the alien groups, as the movements and experiences of the young aliens are controlled by their elders. It’s also present, obviously, in the Earthling’s love of punk. Why should a kid growing up on the edge of poverty, with no job opportunities and no hope for a brighter, happier Britain, care about the Queen’s Jubilee Year? Why should anyone try to create anything new when the world is so grey and dull? How can there be any hope when the economy is flatlining and Thatcher looms on the horizon? Will we, aliens and human alike, evolve, or will we die? As the movie makes beautifully clear, where there’s music, there’s hope. Where a kid spends his time drawing new characters and learning how to think for himself, there’s hope. Where a girl is willing to leave her family on a quest for adventure, there’s hope.

I’ve seen plenty of reviews saying that the movie is messy and unfocused, and to that I say, hell yeah it is. Do you want a clean, precise movie about punk? A thorough-going quantification of love? Fuck that. How to Talk to Girls at Parties is weird and fun and will actually make you feel something, and as far as I’m concerned it’s worth more than all the Solos, Ant-Men, and/or Wasps Hollywood wants to throw at a film screen this summer.

Leah Schnelbach doesn’t need anyone to take her to the punk. She knows that punk is an energy field created by all living things. It surrounds us and penetrates us; it binds the galaxy together. Come slam dance with her on Twitter!