Hans Christian Andersen is primarily known for his original fairy tales, which borrowed images from the stories told to him by his grandmother and other elderly people in childhood, but used their own plots and characters. But from time to time, he also worked with existing fairy tales, adding his own touches to both obscure and better known tales, as in his story, “The Tinder Box,” one of his very first published fairy tales, based on a tale so well known that the Brothers Grimm also collected a version, “The Blue Light,” making this one of the few fairy tales to be both a Grimm and Andersen tale.

The Grimms told their version first, publishing it in the second volume of their first edition of Children’s and Household Tales in 1815 and then, in typical Grimm fashion, rewriting and expanding the tale in later editions. (Most online English translations tend to use either the 1815 or 1857 versions.) A few other scholars also collected at least one Swedish and several different German versions. Andersen may have known one or many of these, or worked from another oral version — but they are all similar enough to be very obviously the same tale.

The majority of the stories start with a familiar figure from fairy tales: the now out-of-work soldier. The Grimms made a point of noting that the soldier was loyal to the king. Most of the other versions remain rather ambivalent about that part. Fired by the king, and lacking other skills (in an echo of the start of another Grimm story, “Bearskin”) the soldier fears starvation. Fortunately, he sees a light off in the forest. Heading towards it, he encounters a witch.

Well, fortunately for him. A little less fortunate for the witch.

After a bit of discussion, the witch agrees to let him do some chores around the house in return for food, drink, and a roof over his head—an echo, perhaps, of similar arrangements entered into by retired and disabled soldiers after the Napoleonic Wars. On the third day of this, she asks him to head into a dry well to fetch her little blue light—a light that never goes out. I immediately had some nasty thoughts of heading into cold, dark, underground places, immediately followed by the more practical thought of telling the witch to get her own light. I mean, sure, if the light is still burning, presumably there’s still enough air to breathe down there—but then again, the witch just said that this is a light that never goes out, thus, presumably magical, and not perhaps the best guide to the available oxygen in the well. And also THE GROUND COULD FALL ON HIM AND BURY HIM ALIVE NEVER EVER EVER LETTING HIM GET OUT WHICH IS WHY NOBODY SHOULD GO UNDERGROUND AT ALL OR AT LEAST NOT FOR LONG but I digress.

The soldier, less worried about dark underground spaces than I am, does go down the well and finds the light—but refuses to hand it over to the witch until she lets him up to the solid ground. Infuriated, she knocks him back down into the well, which seems a slight overreaction. Then again, maybe she figured that another desperate soldier would be along shortly. I mean, it seems kinda unlikely that the king only fired the one soldier. This soldier, meanwhile, decides that the best thing to do when you’ve been knocked down to the bottom of a well is have a smoke, which NO, DID WE NOT MENTION THE ALREADY QUESTIONABLE OXYGEN SUPPLY HERE BEFORE YOU STARTED TO SMOKE? Fortunately for the soldier, the smoke summons, not lung cancer, nicotine poisoning or shortness of breath, but a magical dwarf capable of bringing him unlimited wealth—and revenge.

You might be beginning to see just why Disney has not chosen “The Blue Light” for their next animated fairy tale, and why it’s not necessarily one of the better known fairy tales out there. References to smoking appear in other fairy tales, of course, but rarely in anything close to this: “Smoke, and maybe you too can summon a magical creature and never have to work again!” I won’t say that parents, librarians, and those who hate cigarette smoke have exactly repressed the tale. I’ll just say that they haven’t gone out of their way to celebrate it, either.

I should also note that some English translations simply use “dwarf.” Others specify a “black dwarf”—a perhaps uncomfortable reference given that, as the dwarf clarifies, he has to come whenever he is summoned by the soldier.

In the original Grimm version, the soldier apparently figures that gaining a magical dwarf and taking the light away from the witch more than makes up for her decision to push him into the well. In the later version, the Grimms cleaned this up by having the dwarf take the witch to the local judge, who executes her. Harsh. Come on, soldier dude. You’ve got a magical dwarf and unlimited wealth and you can do anything and you’re getting this woman killed because she pushed you into a well after you refused to give her back her own property? Uh huh. Moving on.

The soldier then decides that the best thing he can do is get revenge on the king who fired him—by kidnapping his daughter, like, soldier, at this point, I’m thinking that (a) the king who fired you had a point, and (b) on the other hand, maybe this is an anti-smoking tale after all, like, start smoking, kiddies, and you too will end up entering a life of magical crime. Hmm. Maybe that’s a temptation for some children. Let us move on. The dwarf is not particularly in favor of the whole kidnapping thing either, but the soldier insists, forcing the dwarf to kidnap the princess at midnight to work as a maid for the soldier until sunrise.

I suppose there’s a bit of revenge porn or wish fulfillment in the thought of focusing a princess to do housework—and the Grimms certainly frequently played with that theme in several tales—and I suppose that the princess might well have agreed with her father that firing the soldier was a good move. Again, I’m having the same thought.

But I can’t help thinking, soldier, that you’re taking your revenge out on the wrong person.

Not surprisingly, the princess notices all this, and mentions it to her father. The two devise a plan to trap the soldier, which eventually—three nights in—works. We then get this great bit:

The next day the soldier was tried, and although he had done nothing wrong, the judge still sentenced him to death.

Wait. What? DUDE. YOU USED A MAGICAL DWARF TO KIDNAP A PRINCESS FOR THREE NIGHTS RUNNING, and I’m not even getting into the part where your dwarf littered the entire town with peas. Again, I’m not against the idea of making a princess do a bit of cleaning, but let’s not claim that you were a complete innocent here.

This all leads the soldier to light up another pipe, summon the dwarf and order the dwarf to kill pretty much everyone nearby—which the dwarf does. Everyone, that is, except for the king and the princess. The terrified king hands over his kingdom and the hand of the princess in marriage, and, look, sure, this is all very typical for a revolution, even tame by the standards of the most recent one that the Grimms were aware of, and yeah, it’s definitely an argument for setting up a pension plan for displaced soldiers, something the Grimms definitely seem to have been in favor of, but still: quite a lot of PRETTY INNOCENT PEOPLE JUST DIED HERE IN ORDER TO MAKE YOU KING, SOLDIER.

Also, starting a marriage off through kidnapping your bride and making her do housework for three nights, keeping her from sleeping, and following that up by having her watch your near-execution, doesn’t strike me as the best foundation for a happy, contented marriage. I could easily be wrong.

Andersen published his version, “The Tinder Box,” in 1835, alongside three other tales: “Little Claus and Big Claus,” “The Princess and the Pea,” and “Little Ida’s Flowers.” It was later republished in two collections of Andersen’s tales—the 1849 Fairy Tales and the 1862 Fairy Tales and Stories, and translated into English on multiple occasions starting in 1846. This was the version Andrew Lang chose for his 1894 The Yellow Fairy Book, bringing it to a wider English speaking audience.

Andersen’s tale also starts with a soldier—though not, it seems, a former soldier cast out into the world. Andersen clarifies that this is a real soldier, looking the part when he encounters a witch. So much looking the part, indeed, that the witch skips right over the three days of farm chores and asks the soldier to fetch her tinderbox immediately.

Here, the tale begins to blend with that of Aladdin, a tale that had haunted Andersen for some time. The tinderbox in this case is not just at the bottom of a well, but in an underground hall, filled with treasures, guarded by monsters. As in Aladdin’s tale, the witch sends another person to fetch her magical object, offering treasure in return, and as in Aladdin’s tale, the soldier refuses to surrender the magical object when he returns. And very much unlike in Aladdin or in the Grimm’s tale, the soldier kills the witch with a single blow himself, without asking for help from supernatural creatures. And with even less justification: the witch in “The Blue Light” had thrown the soldier down a dry well, after all. The witch in this story simply refuses to tell the soldier what she plans to do with the tinderbox. It might, indeed, be something evil. Or she might just want some cash. Hard to say. Still, I’m starting not to like this soldier all that much either: this witch has just made him very, very rich, and this is how he repays her?

To repeat: Harsh.

In any case, loaded with treasure—and the tinderbox—the soldier heads off to town and a little moral lesson from Andersen about how quickly newfound wealth can disappear and that friends interested in your money will not be interested in you when that money disappears. In what I must say is a nice touch, some of that money disappears because the soldier does donate it to charity—another contrast to the previous soldier as well—but still, like Aladdin, the soldier ends up living in a poor state indeed, until he figures out how to use the tinderbox. And even then, like Aladdin, he’s careful.

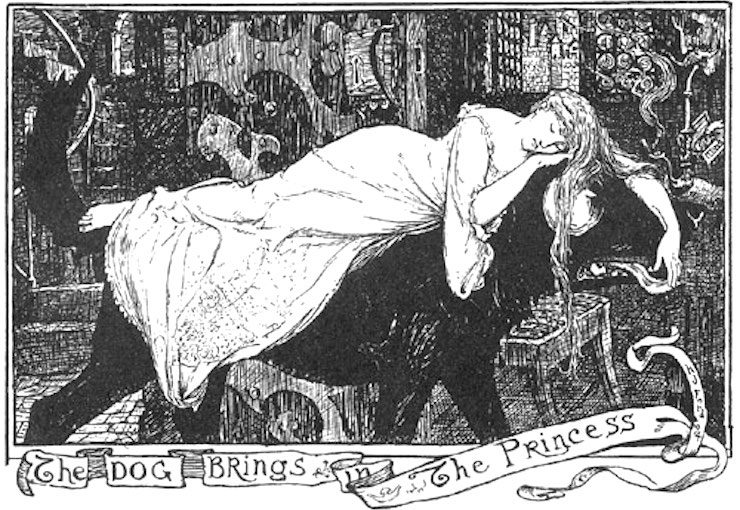

Right up until he hears the tales of a princess locked in a tower. A standard part of fairy tales, though Andersen may also have been thinking of some real life contemporary Danish princesses, locked in prison towers for various reasons. And he was, doubtless, thinking of Aladdin, who also fell in love with a princess locked away from the rest of the world—though Aladdin managed to catch a glimpse of the princess first. Just like his predecessors, the soldier kidnaps the princess by magical means while she’s asleep. Unlike his predecessors, who had the kindness to wake the princess up, the soldier kisses her while she’s still asleep. Also a fairy tale theme. Andersen adds, “as the soldier that he was,” implying that all soldiers pretty much do this sort of thing, which does not make me any fonder of the soldier, but moving on. The princess does not quite wake up, but she does remember something, including the kiss, and so, her mother assigns an old lady from the court to keep an eye on the princess.

Sure enough, the next night the soldier decides that what he really needs for entertainment is another chance to kiss a woman while she’s still asleep—allowing the old lady to witness the kidnapping. Unfortunately, her attempt to mark the kidnapper’s door with a cross is easily defeated by the soldier, who simply puts crosses on other doors in the town.

You’d think that this would clue the soldier into the realization that just maybe kidnapping locked up princesses and kissing them while they’re asleep is not the safest or wisest sort of activity. You would be wrong: the soldier magically kidnaps the princess a third time, and this time he’s caught. Not for long, though. As with the story of the blue light, the soldier strikes the tinderbox, summoning his three magical dogs who kill the king, queen, and several courtiers. After this, he marries the princess—Andersen claims she’s pleased, since this releases her from her imprisonment in the tower—and rules the country.

In some ways, this is even worse than “The Blue Light,” since the king and queen in Andersen’s tale did nothing to deserve their fate—other, of course, than arresting someone for kidnapping their daughter. I am kinda on their side here. This king never fired the soldier, for instance, and easily grants the soldier’s last request. Sure, he rules over a kingdom of people more interested in money and status than true friends, and he’s been apparently been letting a witch live freely in the countryside, but the first is hardly unusual, much less his fault, and the second is just the typical nuisance that virtually everyone in a fairy tale has to deal with.

Then again, these are tales of revolution and overthrow, retold by people still dealing with the aftereffects and shockwaves of the French Revolution. Andersen’s childhood poverty stemmed from many causes, but the Napoleonic Wars certainly didn’t help. the Grimms were direct witnesses of the Napoleonic Wars, events that also impacted their academic careers. They knew of former soldiers and revolutionaries who had made themselves—well, not quite kings, but rulers—and they knew that France had become a monarchy again. They knew that kings could be overthrown.

And so they told these tales, which deal with unemployment, unfairness, and revolution, and assume that for some former soldiers, magic and murder might be their best options.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.