I have talked on this site before about my love of Samuel Delany. I came to Delany a bit late, which I regret—I think he would have been a force for good in my own writing style if I’d read him in high school. But once I fell for him I started collecting his books, and as a result, a large amount of my TBR Stack is older books of his that I ration out carefully so I don’t burn through his whole backlist too quickly. This week I finally read his short story collection, Driftglass.

Buy the Book

Driftglass

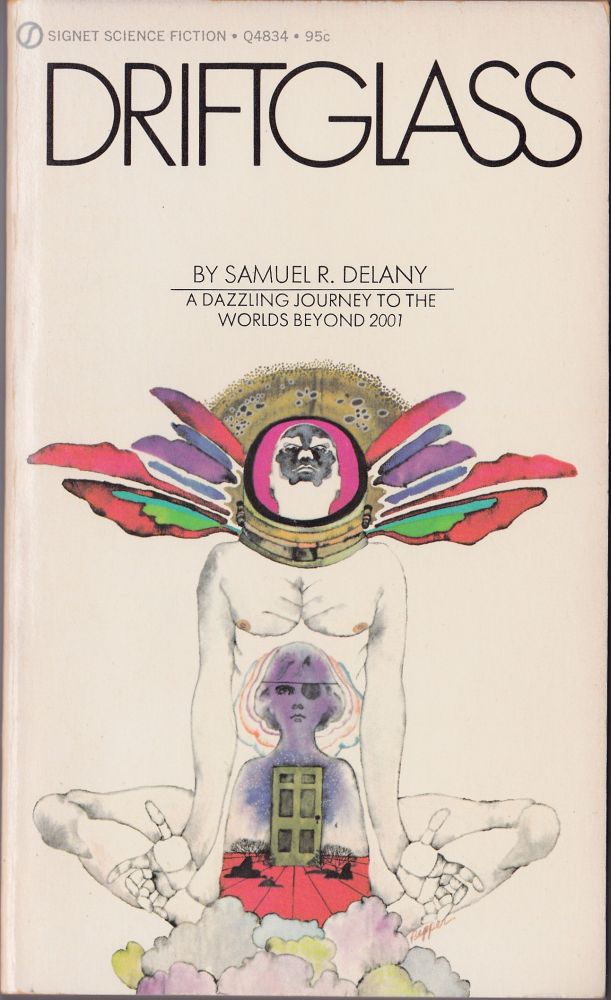

Driftglass was published in 1971—Delany’s first short story collection. It included his first published short story “Aye, and Gomorrah,” which closed out Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions, and was the title story for his later, larger collection. It won the Nebula for Best Short Story in 1968; “Driftglass” was nominated the same year. The penultimate story in Driftglass, “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones” won a Nebula for best novelette, and a Hugo for Best Short Story in 1970. The book’s cover art is pretty salacious as you can see, and the tagline, “A dazzling journey to the worlds beyond 2001” promised the potential reader sci-fi thrills! Futurism! Maybe an angry sentient robot!

Obviously that is not what these stories are about.

Like all of Delany’s work they’re fundamentally about how human minds and lives are shaped by environments, and how people can push against unfriendly environments to create new worlds. In this collection, as in all of his writing, Delany acknowledges class differences, and probes how those differences affect human interaction. He centers conversations on race. He makes a point of exploring his characters’ sexualities. He celebrates workers, and even when his science gets a little hand-wavy, you still know, reading him, that these people he’s writing about have jobs.

But best of all is how these stories are just human stories, about relationships and emotional epiphanies. (They could almost be litfic if Delany wasn’t so fond of writing about telepathic children.) Probably my favorite in the collection is “Corona,” about a telepathic Black girl, Lee, who forms an improbable friendship with a white ex-con, a janitor named Buddy. The story unfolds in the future—Kennedy Airport is now Kennedy Spaceport, and there are colonies on Mars, Venus, Uranus—but Delany carefully deploys mid-20th Century references to ground his readers. Lee and Buddy bond over the music of Bobby Faust, from the Ganymede Colony. The mania that greets Faust’s every concert is an echo of Elvis-and-Beatlemanias before it. The prison that Buddy did his time in sounds every bit as cruel and inhumane as current Angola. When Buddy needs to refer to his friend the telepath, he uses phrases like ‘colored’ and that one that starts with an ‘n’ that I won’t type—not from cruelty or racism but simply because those are common terms, and he sees nothing wrong with them. We get the sense that Lee is middle class, and Buddy is a hick from the South, but they’re both tortured and trapped by the circumstances of their lives. They both find momentary relief in music, but once the song ends Buddy has to go back to his crappy job and dead-end life, and Lee has to go back to tests in the lab.

The relationship between them is pure platonic love. There’s no sexuality here. But in this collection “Corona” flows into “Aye and Gomorrah” which is explicitly about the tangle of adolescence, sexuality, asexuality, and something that sits uncomfortably close to pedophilia. We’re introduced to “Spacers,” adults who were neutered at puberty to make them fit for space travel, and “frelks,” people who are sexually attracted precisely to the Spacers’ inability to reciprocate attraction. The Spacers seek out places like dockside dive bars and gay cruising spots, seemingly searching for a sexual connection knowing they can’t have it, and then they seek out the frelks even though they resent them. Delany makes a point of showing the reader that queerness is, if not completely accepted by society, mostly ignored to an extent that it was not at the time the story was written. He’s explicitly not creating a parallel between the frelks’ nearly pedophiliac desire and the relationships between gay and bisexual adults. Instead he’s complicating desire itself, and again pulling class issues and questions about consent and oppression into that conversation. The Spacers are not children now. They’re consenting adults who often choose to hook up with the frelks to make some extra money. But their choices were taken away from them at puberty, before they could consent, and their adult lives exist in the echo of that violation. Meanwhile the frelks are not condemned—their desire for desire itself is treated compassionately.

You don’t choose your perversions. You have no perversions at all. You’re free of the whole business. I love you for that, Spacer. My love starts with the fear of love. Isn’t that beautiful? A pervert substitutes something unattainable for ‘normal’ love: the homosexual, a mirror, the fetishist, a shoe or a watch or a girdle.

…and they’re not preying on children…but they are benefiting from the spacers’ trauma.

“Aye and Gomorrah” is a response to Cordwainer Smith’s “Scanners Live in Vain.” Smith’s story looks at two groups of people, ‘Habermans’ and ‘Scanners,’ who go through hellish medical procedures to cut themselves off from physical sensations, making them fit for space travel. Habermans are prisoners sentenced to the death penalty, who are instead, essentially, zombified. Scanners are ordinary citizens who choose the procedure, joining an elite group of people. The story plays with imagery from The Island of Dr. Moreau, and is, to some extent, about free will and what makes a human a human. It’s a study in forced liminality, and very much a commentary, like “Scanners” and “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” about what we’re willing to stand as a society. But since “Gomorrah” was written by a Black man who [as far as I know] refers to himself as gay, but who also had a longstanding romantic and sexual relationship with a white woman (who was also dating women on the side throughout their marriage) that “we” is complicated.

Having a story like this written by someone who is at the exact nexus point of oppression, lack of power, lack of what Roy Cohn would call clout—Delany is coming at this conversation from a place of enforced vulnerability. He knows, writing these stories that many of his readers will think him sub-human, if not for one reason then another. The ones who think they’re not racist still might bristle at his white wife and mixed-race child. The ones who are all for civil rights might be disgusted by the gay stuff. The ones who consider themselves queer-friendly might balk at the open marriage. The ones who are cool with all of it might be horrified at the idea that he chose to breed. A lot of people on this earth love boxes more than they want to admit, and they want to fit people into those boxes so they can feel comfortable. (I think most people’s minds are basically The Container Store—you want to close the plastic lid and slap a neatly-Sharpied label on everything around you, because that’s a strategy for sanity in a chaotic and terrifying world.) So Delany’s idea of society and what is owed to it is significantly different than that of a white straight writer.

“Driftglass” gives us a different type of dangerous-ass job that involves physical modification at puberty. Here we meet amphimen—people who are outfitted with gills and webbing so they can be fit for deep-sea exploring. This is necessary because people need cables laid beneath the sea, they need to know where to fish, they need, always, more power. So young people are sent off to the frontlines to work underwater, and sometimes underwater volcanoes kills them in horrifying ways. We meet our protagonist, Cal, about twenty years after the accident that left him with a false leg and deformed face. He’s made a life for himself on the beach, gets a pension, has lots of friends. But of course another generation of young amphimen are planning to lay a cable in the same trench where he had his accident, and of course he’s going to feel a lot of different ways about that.

Here again—the powerless have to provide conduits for power for people who will never know or appreciate the danger. And yet. A job well done is celebrated; working-class people are every bit as smart and poetic as any academic; the act of being liminal is both a sacrifice and a source of joy; there are many ways to love; there are many ways to be human.

“We in Some Stranger Power’s Employ, Move in a Rigorous Line” continues Delany’s exploration of power. The story sounds funny—a roving IT department who trundles along the world’s power lines, fixing cable and making sure everyone is hooked up to the grid. This sounds like it could be some sort of silly Office-style story, maybe something like The Space Merchants…but, Delany. The stakes are laid out by Mabel, the leader of the team, when she describes the society that is being protected by the power grid:

Men and women work together; our navigator, Faltaux, is one of the finest poets working in French today, with an international reputation, and is still the best navigator I’ve ever ad. And Julia, who keeps us so well fed and can pilot us quite as competently as I can, and is such a lousy painter, works with you and me and Faltaux and Scot on the same Maintenance Station. Or just the fact that you can move out of Scott’s room one day and little Miss Suyaki can move in the next with an ease that would have amazed your great-great ancestors in Africa as much as mine in Finland. That’s what this steel egg-crate means.

The IT team are called demons or devils, depending on their rank within the company. Of course they run afoul of some angels—in this case a group of neo-Hell’s Angels, bikers from around the year 2000 who drew on the imagery of the original, mid-20th-century Hell’s Angels. But this being the future, these angels can literally fly, on black winged bikes called pteracycles, which are more colloquially known as broomsticks. (So rather than symbolically-charged red wings we get black wings.) The angels live in an aerie – an abandoned mansion in Canada, and soar among the clouds while the devils work underground on the cable. The angels are smiths, laborers, and thieves, but the demons represent real power…but the angels also live according to a fairly barbaric code of gender, their seemingly gentle smithy is also an attempted rapist, domestic violence seems pretty normal, and problems are sorted out through ‘rumbles’ which are exactly what they sound like. The whole thing was written as a tribute to Roger Zelazny, it was written in his ironic, rollicking style, and he appears as a character – the leader of the Angels.

The story is marked with a timestamp of 1967, thus putting it the year after Delany’s novel Babel-17, and it feels a lot like Babel-17 to me, with a large crew of polymaths, an unchallenged female commander, an easy sensuality among the crew, and, especially, immediate respect for people who in some stories would be the Other. Think about other ways this story could go: enlightened people descend upon be-nighted rubes and give them the gift of internet; enlightened people are torn to shred by the be-nighted; tentative love sparks between an enlightened and a be-nighted, only for tragedy to strike, driving the pair apart forever; the enlightened could look into the savage heart of life; one of the enlightened could sexually exploit on of the be-nighted; one of the enlightened could find themselves in over their head, sexually speaking. I could spin variations on this all day—and some of these things do, kind of, happen. But they’re all filtered through Delany’s extraordinary empathy. There is nearly a rape, but it’s pretty clear that the near-rapist has no idea that what he’s done was wrong. There is some tar-crossed love, sort of, but that love unfolds in such a clashing set of coded gender norms that neither party really has the chance to hurt or be hurt. There is a violent tragedy, but it’s clinical, necessary, and absolutely intentional. There is no correct answer. There is no right way to live.

During Delany’s brief and efficient description of the IT team’s tank (called a Gila Monster) he low-key invents the internet:

Three quarters of a mile of corridors (much less than some luxury ocean liners); two engine rooms that power the adjustable treads that carry us over land and sea; a kitchen, cafeteria, electrical room, navigation offices, office offices, tool repair shop, and cetera. With such in its belly, the Gila Monster crawls through the night (at about a hundred and fifty k’s cruising speed) sniffing along the great cables (courtesy the Global Power Commission) that net the world, web evening to night, dawn to day, and yesterday to morrow.

Again, this is 1967, and a worldwide cable is referred to as both a net and a web in the same sentence. The cable has many uses, some of which give people access to a worldwide computer system if they want it (the way this is written makes me think that this is a lesser desire) as well as local TV and radio. The cable is civilization, and naturally some people don’t want it. Some people don’t even want access to it, because they know that given access, people will gradually forsake their old ways and use it, no matter how hard they might resist at first. Once again people are doing a difficult, even dangerous job, for the good of the world. Once again class divisions of white and blue collar are disregarded.

Which leads me to the thing I like the very very best: the fact that Delany writes with sheer exhilaration about people from every strata of society. In the collection’s opening story, “The Star-Pit,” Delany creates ‘golden,’ people who can, for complex physiological reasons, survive the vasts of space. And there isn’t just a telepathic child—there’s a telepathic child who can project visions she sees in peoples’ minds. But having shown us these weird sci-fi constructs, we instead spend most of our time hanging out with Vymes, a grieving mechanic. Delany showers him with language like this:

I was standing at the railing of the East River—runs past this New York I was telling you about—at midnight, looking at the illuminated dragon of the Manhattan Bridge that spanned the water, then at the industrial fires flickering in bright, smoky Brooklyn, and then at the template of mercury street lamps behind me bleaching out the playground and most of Houston Street; then, at the reflections in the water, here like crinkled foil, there like glistening rubber; at last, looked up at the midnight sky itself. It wasn’t black but dead pink, without a star. This glittering world made the sky a roof that pressed down on me so I almost screamed…That time the next night I was twenty-seven light years away from Sol on my first star-run.”

Just spend a second here with me. You’re hopping from the rarefied, world-tilting description of the Manhattan Bridge as an “illuminated dragon” and then you swoop all the way down to the water looking like “crinkled foil.” We’ve all seen crinkled foil. The sky isn’t black it’s pink, a terrifying, jarring color for a midnight sky to be, and then the whole world spins completely as Manhattan, Brooklyn, and this creepy pink sky all become a roof trapping the narrator. And then Delany in the space of a couple words takes us from New York, which we’ve seen a thousand times on everything from Taxi Driver to The Avengers to Friends, and hurls us twenty-seven light years away. And again, we’re not in the company of a physicist or a Chosen Hero or an astronaut—this guy’s a mechanic. But his life deserves to be describes with just as much poetry as a ballet dancer’s or a neuroscientists. In “Driftglass,” a girl comes up and taps on the protagonist’s window, but since we’re in Delany’s world we get: “At midnight Ariel came out of the sea, climbed the rocks, and clicked her nails against my glass wall so the droplets ran, pearled by the gibbous moon.” Hey, maybe you want to tell your readers it’s blustery outside, and also nighttime? I mean, I guess you could just say, “it was a blustery night,” but if you’re Delany you might want to say: “Evening shuffled leaves outside my window and slid gold poker chips across the pane.” Everyone’s lives, no matter how screwed up or prosaic, get the same gorgeous elevated language. Beauty is not only for those who can afford it in Delany’s worlds.

Leah Schnelbach knows that as soon as this TBR Stack is defeated, another will rise in its place. Project your telepathic powers at her on Twitter!