Not to be too much of a killjoy, but friendly reminder: Each of us makes the planet a little bit worse.

Every day, we make an uncountable number of decisions. Big decisions, like whether to have kids. Smaller decisions, like deciding to drive to work or get a new iPhone. And decisions so tiny they barely register: Ordering a cheeseburger. Drinking a bottle of water. In the grand scheme of things, each of those choices has an infinitesimal impact. It’s only later, when combined with others’ actions, that we see our choices’ consequences: Overpopulation. Climate change. Human rights abuses. Deforestation. Garbage patches in the Arctic.

Paolo Bacigalupi’s ecologically focused work is shelved as science fiction, but horror might be a better fit. In The Wind-Up Girl, he considered what life could look like when towering walls protect cities from rising seas, and where corporations’ genetically modified crops annihilate the food chain. In The Water Knife, his drought-cracked American Southwest is home to those who control dwindling supplies of fresh water—and thus who lives and dies. Bacigalupi’s visions are intoxicating and terrifying; these futures aren’t so much possible as they are probable.

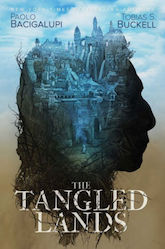

With The Tangled Lands, Bacigalupi and Tobias S. Buckell create a shared fantasy world, with each contributing two novella-length stories. (Two of these stories were released in 2010 as an audiobook, The Alchemist and the Executioness; a year later, they were published as separate novellas.) Buckell and Bacigalupi imagine the melancholy remnants of a once-grand empire, where magic-using citizens once lived in comfort. They used magic to craft, to conquer, to heal. They used magic to keep hearth fires burning, and they used magic to build palaces that floated on clouds.

But each of those magics had a cost.

Buy the Book

The Tangled Lands

The bramble—a writhing, insatiable growth of cruel vines and deadly seeds—was attracted to magic. Even the smallest spell attracted a sprig of lethal, quick-growing bramble, and cities—where magic was most concentrated—lured bramble into streets, into homes, into flesh. By the time The Tangled Lands begins, bramble covers the land, and people are forbidden from using magic.

Few comply. After all, in the grand scheme of things, each of their spells has an infinitesimal impact.

Buckell and Bacigalupi’s tales in The Tangled Lands mostly take place in Khaim, a largely bramble-free city split by the river Sulong. Those in Lesser Khaim—many of them refugees from bramble-stricken lands—scratch out lives of poverty. Above the slums, in comfortable homes and estates, live the dukes and rulers. The poor are killed if caught using magic; the rich pay others to cast spells for them, or devise ways to hide their magic.

Khaim feels alluring and ancient, weighted with the satisfying heft of history. It’s also familiar, as neither author is interested in hiding the book’s environmental allegory. “The bramble would never be banished,” writes Bacigalupi. “They might slash and hack and torch the thorny woods, but in the end, they sought to shove back an ocean.” Likewise, neither author is sneaky about the book’s political echoes. “I saw a human, and a wrinkled old one at that,” remembers one of Buckell’s characters. She stands before a ruler of Khaim who wields power with entitlement, greed, and nepotism, and who seems a whole lot like somebody. “Yet, this flabby-skinned creature could kill us all.”

Bacigalupi’s contributions—the first tale, “The Alchemist,” and the third, “The Children of Khaim”—are the shortest and most effective. “The Alchemist” follows Jeoz, an aging man struggling to invent a device that can drive back the bramble, even as he casts spells to keep his ailing daughter alive. (“And it was only a small magic,” he tells himself. “Really it was such a small magic.”) When his creation shows signs of success, he presents it to Khaim’s mayor and Majister Scacz, the one man in the city allowed to practice magic. While Jeoz hopes to save Khaim from the “the plant that had destroyed an empire and now threatened to destroy us as well,” the mayor and Scacz have… different intentions.

Buckell’s installments alternate with Bacigalupi’s, and The Tangled Lands’ second part, “The Executioness,” has a decidedly different tone: Tana, a mother and wife, is forced to take up her father’s profession, executing those caught practicing magic. But following a raid on Lesser Khaim, she finds herself in a traveling caravan, saddled with a reputation she grudgingly comes to embrace. “The Executioness” reads like an adventure story, but the raiders’ religious fanaticism gives it a sharp edge—they know that the horrors of bramble, while caused by some, are felt by all. “You can’t help yourselves,” one whispers, “and we suffer all together as a result.”

“The Children of Khaim” returns us to the troubled city—and introduces a shadow economy. Those stung by bramble fall into a coma, and often, their still-warm bodies—“dolls”—are kept in candlelit rooms, “stacked upon the floor, piled by age and size,” waiting “for the men of Khaim to do whatever they wanted to the young, unmoving bodies.” In news that will surprise no one, “The Children of Khaim” is the most sinister of The Tangled Lands’ already-sinister tales; it’s also the one that offers the best look at how Khaim’s lower classes fight to survive.

Buckell’s “The Blacksmith’s Daughter” closes out The Tangled Lands, and it’s similar to “The Executioness”—a driven woman finds unexpected strength in a world intent on punishing her for her poverty and gender. If the two stories share the same arc, though, at least it’s a good arc, and in both, Buckell makes the vague magic of The Tangled Lands tangible. When Tana witnesses a bit of state-sanctioned magic, it lingers in the air: “It tasted of ancient inks, herbs, and spices, and it settled deep in the back of my throat.”

In their afterword, Buckell and Bacigalupi write of their “many hours on Skype brainstorming, chatting, and (let’s be honest) drinking, as we created this world and the people who inhabit it.” That shared passion is clear, particularly when their stories cleverly inform and complement each other. But by its final pages, The Tangled Lands occupies an awkward middle ground: It’s not quite significant or unified enough to feel like a novel, yet its parts aren’t independent or far-ranging enough to have the appeal of a story collection.

There’s something else in that afterword, too: A note that the authors “hope to have many more opportunities to revisit Khaim and its many tangled stories.” I hope so, too—given its discomfiting parallels, Khaim is a place I might not be happy to revisit, but I do feel compelled to return, especially if Bacigalupi and Buckell find a way to explore it with more focus and propulsion. As is, The Tangled Lands feels like a well-imagined beginning, like there’s more to see and more to be said—not only about the choices made by those in Khaim, but about the choices made by each of us.

“It’s not as if the people of Jhandpara—of all the old empire—were unaware of magic’s unfortunate effects,” Majister Scacz tells Jeoz. “From the historical manuscripts, they tried mightily to hold back their base urges. But still they thirsted for magic. For the power, some. For the thrill. For the convenience. For the salvation. For the wonderful luxury.” Changing people’s habits, though, is easier said than done. “Even the ones who wished to control themselves lacked the necessary will,” Scacz adds. “And so our empire fell.”

The Tangled Lands is available February 27 from Saga Press.

Read an excerpt here.

A writer, editor, and male model, Erik Henriksen lives in Portland, Oregon. He’s written for the Portland Mercury, The Stranger, i09.com, Wired.com, and Tor.com. (Hey! That’s this site!) Learn all you ever wanted to know and more at henriksenactual.com.