Twenty-five years ago Tony Kushner’s Angels in America came to Broadway. It was an audacious work of theater, somehow meshing a realistic depiction of the havoc AIDS wreaks on a body, complex discussions of American political history, pissed-off angels, and Mormonism. The ghost of Ethel Rosenberg was a character, as was Roy Cohn. Gay and straight sex happened onstage. Audiences were confronted with both Kaposi’s Sarcoma lesions and emotional abuse.

And somehow, miraculously, the show was hilarious.

Now Isaac Butler and Dan Kois have undertaken the herculean labor of creating an oral history of the play, made up of interviews with hundreds of people, from Kushner himself all the way to college students studying the play. The result is an exhaustive look at creativity and theater that is nearly as exhilarating and fun to read as the play itself.

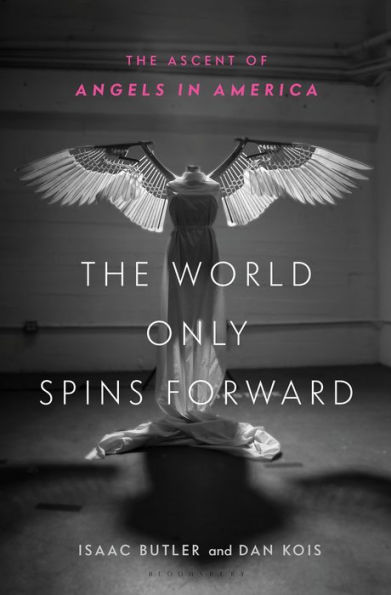

Buy the Book

The World Only Spins Forward: The Ascent of Angels in America

Let’s begin with a tiny bit of backstory. Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes is an epic play in two parts. Tony Kushner began writing it in the late 1980s, and it came to Broadway in 1993 (Part I: Millennium Approaches) and 1994 (Part II: Perestroika), winning Tony Awards in both years. It follows Prior and Louis, a gay couple whose relationship falls apart when Prior is diagnosed with AIDS; Joe and Harper, a straight couple whose relationship falls apart when Joe finally deals with the fact that he’s gay; Roy Cohn, a real-life lawyer and political fixer who mentored a young up-and-comer named Donald Trump; Belize, a Black drag queen who is Prior and Roy’s nurse; and a group of Angels who want to stop human progress. You can read some of my many thoughts about the play here.

I always worry about falling into hyperbole when I’m talking about Angels in America. It’s complicated. This play made me a person. It formed me, along with Stephen King and Monty Python and a few other choice cultural moments. Kushner made me what I am: socialist, mouthy, long-winded, overwrought, (hopefully, sometimes) funny, and deeply, deeply neurotic. (It’s also why my posts tend to run long—this play taught me the glories of maximalism even before I read David Foster Wallace.) Kushner still stands as my best-ever celebrity sighting: during my first months in New York, I went to work in the Reading Room of the New York Public Library, and there he was. I couldn’t get any more work done that day—the idea that I was attempting to write in the same room as this person was too huge. I am still so, so happy that this happened at the Reading Room, where I wasn’t able to embarrass myself by talking to him.

All of this is to say that The World Only Spins Forward made me happy.

The best oral histories make you feel like you were there, or at least make you desperately wish you had been there. I think there’s no better way to tell the story of Angels in America than an oral history. The cacophony of voices coming together, sometimes arguing, sometimes agreeing, sometimes teasing or revealing heartbreak is such a perfect fractured mirror for the multi-faceted play. Butler and Kois have done stellar work here, including interviews with people from Kushner’s original New York theater troupe, people at the Eureka Theater and the Mark Taper Forum, and then-students who worked on college theater productions, in addition to spending time on the Broadway production. And they show how the play has evolved over the decades by talking to people from Mike Nichols’ 2003 HBO adaptation, productions from Europe and New York throughout the ’00s, and come all the way up to this year to talk to director Marianne Elliot and actors Andrew Garfield and Nathan Lane as they work on the current production that’s hitting Broadway next month. Each voice is given space and attention, from Tony-winners to high school teachers who are introducing the play to their students.

Butler and Kois set the life of the play against the larger history of the gay rights movement. This is a brilliant move that helps show the conversations going on around the play, some of what it was responding to, and some of what it helped to change—more on that below.

They create a perfect balance between the politicians working for gay rights and the struggles of the artists coming together to bring the play to life. Much time is spent on Kushner’s deadline-blowing ways—but it’s not that he’s ever lazy, simply that the play grew as he wrote it. Butler and Kois also give the sense of how scrappy young artists need to be, as Kushner borrows money, applies for grants, and works on side hustles to keep a roof over his head while also devoting himself to this massive project, as his actors and collaborators are working jobs in catering, temping, and dealing with health issues the entire time. It’s an amazing thing to read this book, to be a person whose life was changed by this work of art, and then to see just how precarious AiA’s creation was.

The core group who collaborated with Kushner, including dramaturges Kimberly Flynn and Oskar Eustis, and actor Stephen Spinella, came together in New York while most of them were grad students of one type or another. They worked on a few projects before Kushner started writing AiA:

Stephen Spinella: “A poem for the end of the apocalypse.” There was a whale ballet in which a choreographer danced en pointe with a sousaphone.

And sometimes they had to make do with the spaces available in New York:

Tony Kushner: We rented a theater on 22nd Street, one floor below a Korean S&M bordello, “At the King’s Pleasure.”

before moving out West to mount the first productions with San Francisco’s Eureka Theater and Los Angeles’ Mark Taper Forum. You can see as the accounts go on that the theater company was outgrowing itself—as was the play. As with the best oral histories, the accounts don’t always agree, but you get the sense that the play was expanding, until what was originally supposed to be a single, two-hour-long work became two plays that added up to a seven-hour running time.

Kushner: I really had gotten into trouble, I knew because my outline said that the Angel was gonna come through the ceiling before intermission, and I had written 120 pages, which is the length of—that’s two hours at a minute per page. And I wasn’t—she hadn’t come through the ceiling yet.

But this book is not simply a biography of Tony Kushner, or a look at his writing process. As much as it interviews him, and gives you wonderful glimpses into his giant brain, it also highlights the fact that theater is a socialistic art. It is teams of people all working together in their own expertise to create a unified experience. A communal experience. Going to a movie tends to be more passive: you sit in the theater, watch the show, and maybe you note the audience reactions, where other people are laughing or crying. Maybe you notice that someone’s talking or texting (go straight to hell, btw) or that someone’s an excessively loud popcorn chewer (…that one’s probably me) but watching a movie is like looking up at the stars—all of these actions and emotions were committed to film months or even years ago. But in theater all of the emotions are happening right now, and the actors are feeding off of the audience’s energy in the same way that the audience is immersing themselves in the drama. If there’s an intermission you’re milling around with people who are currently in the middle of a shared experience.

We dip in and out of hundreds of different consciousnesses here. We hear from Justin Kirk and Ben Schenkman (Prior and Louis in the HBO adaptation) about the experience of working with Meryl Streep and Al Pacino (Hannah and Roy Cohn). We hear about the attempted film adaptation with Robert Altman that never got off the ground. We get adorable anecdotes from people like Zoe Kazan (Harper in the 2010 Signature Theater production) who says, “I’m not a religious person, but I get nervous flying, and I say Harper’s entire speech whenever a plane takes off and whenever it lands.” And former Spider-Man Andrew Garfield, playing Prior in the current Broadway production, talks about experiencing the play as a movie first:

I had seen Mike Nichols’ HBO two-parter, when I was studying in drama school. It was one of those things that was just on a loop, on repeat in our shared actor house. There were a few DVDs we would watch over and over and that was one. Uta Hagen’s acting class was another, Eddie Murphy: Delirious was the third, Labyrinth was the fourth.

But we also hear about a student production at Catholic University and a regional theater production in Charleston that each caused controversy among conservative groups, and several different European productions. The thing to note in all of these is that the play is an ever-evolving document. The HBO film, if anything, played up the fantasy element, riffing on Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête and highlighting Ethel Rosenberg as a very real, albeit dead, character. The Toneelgroep Amsterdam production, on the other hand, stripped most of the fantasy out, defining Prior’s angelic visitations as hallucinations caused by AIDS meds, and cutting out his final, optimistic benediction, in order to underline the ravages of the disease.

There’s an entire chapter on the evolution of Belize, told mainly by the people who have played him. Belize is the heart of the play, and easily the most important character, so by giving him his own chapter Butler and Kois allow the actors and critics to think through the development of the character, the knotty issues he brings up, both in the play and in the metatext around the writing of the play. Belize began life as a Black drag queen, who is Prior’s best friend and nurse to Roy Cohn. He was loving to Prior and angry with Louis, Prior’s shitty boyfriend, but his job required him to be at least professionally kind to Roy Cohn. He gets one incredible monologue in Millennium Approaches, in which he takes Louis to task for his guilt-ridden, neo-liberal beliefs—but he doesn’t have an interior life, apart from “friend of Prior’s.” Some of the actors and Kushner’s friends began questioning the fact that the play’s only black character is in service to white characters—often literally—so as he wrote Perestroika Kushner not only made it clear that Belize has a long-term boyfriend “uptown” (implying that he’s part of a social circle that his white friends aren’t in) but he also, crucially, redefines his relationship to Roy Cohn. Belize gets a second monologue, a great, towering description of heaven which he unleashes on Cohn when the man is weak and vulnerable. The vision disturbs Cohn, and, depending on how it’s played, the scene can read as an assault. This is important because Belize, as several of the actors point out in the book, hates Roy Cohn. This isn’t an academic thing, this isn’t based in socio-political theory—Cohn doesn’t even see Belize as a person. The monologue allows the audience to see just how hard it is for Belize to keep his true feelings in check as he cleans the man, feeds him medicine, literally keeps him alive, all while he’d rather see him dead. Belize stands in for all the people who had to care for their friends when the government and the medical industry wouldn’t, and he also stands in for all those people who were paid (badly) to care for racists and homophobes who despised them. But, crucially, he’s also a real, three-dimensional person in the second half of the play, not just a progressive prop.

And this is what makes the ultimate scene of Belize attempting to forgive Cohn so important. It’s this that gives the play its power, beyond all the wit and the visions of a Jean Cocteau afterworld. Belize’s heart, that can find room in it even for Roy Cohn, is the thing that will make this play as immortal as humanity ends up being.

But for me the most resonant aspect of The World Only Spins Forward was charting the cultural shifts over the course of the play’s history. Rather than just being a triumphant, neo-Hegelian rise into an inclusive future, Butler and Kois are not afraid to interrogate how the play changes in a more conservative time. Tony Kushner mentioned seeing the production in London in summer 2017:

It was weird: When I went to London, they were doing Act 2 of Perestroika, and it absolutely hadn’t occurred to me how different something called the “anti-migratory epistle” was going to sound—I mean, I just have not thought, with all the endless talk of travel bans and stuff, that suddenly there’s gonna be huge impact when those words are spoken. “Stop moving,” specifically about not migrating.

And it’s this idea, that the play’s meaning shifts as the culture does, that takes us into the larger conversation this book invites. Butler and Kois give a few pages to the two Tony Awards shows where Angels in America was nominated and Ron Leibman (Roy Cohn) and Stephen Spinella (Prior) won. They reference the speeches. But rather than dwelling on that as a glamorous “Now Angels has arrived!” type moment, they scatter the excitement of the Tonys around anecdotes from the first national touring cast.

These were the people who took Angels across America, into smaller cities and smaller towns. They were the ones who faced down Fred Phelps and any other picketers who showed up to the theater each day. They were the ones who held young queer people as they wept, having seen their lives reflected honestly on stage for the first time. They were the ones who acted as witnesses to young person after young person coming out to their parents during the intermission of the play. They were the ones who brought Angels to America.

It’s a great balance between showing the towering critical achievement of the play, honoring that original (extraordinary) Broadway cast, and also showing the importance of the work the touring cast was doing by bringing the show into smaller communities. It also creates an amazing sense of zeitgeist. This was 1993. When people came out, the language around it was “he confessed to being gay; she admitted to being a lesbian” as though they were crimes, and that shame was the only natural response to same-sex desire. But over the course of two years this country went through a seismic shift. Angels in America and Kiss of the Spider Woman swept the Tonys in June 1993, and Stephen Spinella accepted his award and thanked “my lover, Peter Elliott, the husband of my heart” onstage, and was immediately beset by questions of how much “bravery” it took for him to thank his partner. (The New York Times, reporting on the awards show, said that Spinella “was conspicuous in not wearing a red AIDS ribbon, but rather a button for Act Up, the AIDS protest group.”) Philadelphia came out six months later, starring America’s Sweetheart, Tom Hanks, as a man dying of AIDS. And yes, the filmmakers had to cast Antonio Banderas as his boyfriend to try to push American cinema-goers into accepting a gay couple into their hearts and movie screens—but at least they were portrayed as a loving couple. Six months after that, Hanks won his first Oscar, and delivered a speech that referred to victims of the AIDS epidemic as “too many angels walking the streets of Heaven” which managed to be a play on Bruce Springsteen’s theme song, a riff on Angels in America, and, obviously, a really good way to get Middle America (wherever that is) to start sniffling in front of their TVs and decide that maybe gay people are people.

My point here is that it’s easy to dismiss this as just a niche theater thing, or to wonder if a play—even a very long one—deserves a 417-page oral history. But this isn’t just a history of this play, it’s a history of a time in America, and the absolute sea change that this play was instrumental in causing. The book is dotted throughout with sidebars about high school and college productions of the play. A teacher in Cambridge MA talked about teaching the play to modern teens who have grown up in a much more queer-friendly world:

What can often be a challenge is for modern young people, who are much bolder and willing to speak their truth, is to get them to understand that, in the past, people could not come out. We talk a lot about how times have changed and what it meant for these characters or people in my generation to have to hide their identity.

After I finished the book, and mulled over what to write about in this review, what I kept coming back to was this quote, and how it resonated with my own high school experience. What I thought about most was The Look.

For those of you lucky enough to never get The Look: imagine someone eating in their very favorite restaurant—a fancy, expensive, culinary treat. And halfway through the meal they happen to reach under their chair for a dropped napkin and their hand brushes a desiccated rat corpse that has been under their chair the entire time. The look they give that ex-rat? That’s The Look.

I got it for saying things people didn’t find funny, for flirting with women, for loudly championing gay rights during class. Was I a loudmouthed jerk? Yes. Was I correct to push for acceptance? Hell yeah. And when I look back at my teen years all I can think is how “lucky” I was….that no one kicked my ass for demanding the same respect the straight kids got. (The fact that I’m living in a society where I sigh with relief that no one beat me up for being queer [just threatened to] or raped me [threatened that, too]—that’s fucked up, no?) The consistent throughline of my adolescent experience was The Look, from other kids, from adult strangers, from teachers, reminding me over and over again that I wasn’t acceptable. There are places in this world where The Look is codified into law. There are people in this country who will not rest until it is codified here.

But The Look gave me one great gift: I have never operated under the delusion that anyone is required to consider me human.

I came by this knowledge honestly, as a queer person, but again, I had it easier than many, many people. But here’s the thing. I risked my safety and my body every day, intentionally, to push people’s buttons and force them to reckon with me. I did that so the kids who came up after me wouldn’t have to, and I know that because of those who came before me I was so much safer than I could have been. And now we have kids who find the idea of a closet unthinkable. But there are people in this country who will do anything to take us back to Reagan’s America, or something even harsher and more hateful than Reagan’s America.

My point is this: when people produce Angels in America now, or teach it in class, it’s often seen as a period piece, a look at life in a specific, shittier time. And I would argue that it is not that at all.

“The World Only Spins Forward” is a quote from the play, and the choice to make this the title, and to frame this oral history as a history of gay rights, is very telling to me. The book covers the time period from 1978 until 2018. Each “Act” begins with a timeline of political news, gay rights triumphs and setback, and notable moments in either Angels in America’s history or Kushner’s life. The effect that this has is twofold: first you see how long Angels has been part of the national consciousness, and how much it has interacted with history. But you’ll also notice, with a sinking feeling, just how thin a slice of time it’s been since (most) queer people (more or less) had human rights (at least a few). The world might spin forward, but our culture does not—it’s pushed forward through our own work. And right now there are people, as there have always been, who are throwing their arms round our only world and doing the best they can to spin it the other way.

We have to make a choice each day: how are we going to keep moving? How will we avoid the stasis that our lesser angels so desperately want? How can we enact the compassion of Belize in a world full of Roy Cohns? This is the question the play asks, and the moral imperative it imposes upon its readers and viewers. This is the question this book is asking with its terrifying framing device. We can not become complacent, or think that anything is past, or believe, as Louis does, that simply re-litigating the McCarthy Hearings will save us now, or believe, as Joe does, that keeping a public veneer of placid 1950s values will hold society together. As Cohn points out, what this country truly is is raw meat and churning digestive juices. As Belize points out, it’s a land holding freedom just out of reach of most of its people. As Prior points out, it’s still our best hope at more life. Only by holding all three of those truths in our heads as self-evident, at all times, are we going to keep spinning forward.

The World Only Spins Forward is available from Bloomsbury.

Leah Schnelbach aspires to being very Spielbergian. Come talk angelology with her on Twitter!