In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

The paths to science fiction fandom are numerous. Some people are hooked by a movie, a paperback picked up at an airport, a TV show, a book loaned by a friend, or a musty-smelling stack of magazines in the corner of a basement, and the joys of reading open up to them. For many years, a major source of books for young readers has been the Scholastic Corporation. They distribute books and educational materials by mail order, through book fairs, and more recently via the internet, and among these offerings have been many science fiction and fantasy tales. Today, I’m looking at two I read in elementary school, The Runaway Robot and Revolt on Alpha C.

My son and granddaughter joined us for lunch the other day, and my granddaughter proudly showed me the book she was currently reading, Wings of Fire: Talons of Power by Tui T. Sutherland. She was showing me the map in the front (is there anyone who doesn’t love a book with a map in it?), and the pictures of the various races of intelligent dragons that occupy this imaginary world. And I noticed it was published by Scholastic Press. That name was enough to open the floodgates of memories to me. I remembered Scholastic as a major source of books in my youth, poring over the brochures and ordering lists sent home with me from school, the book fairs with tables full of treasures, and many discussions with my mother regarding the financing of my desired purchases.

A few days later, I went into my basement den, and on one of the top shelves, behind a row of Star Wars characters, I found a collection of some of the first books I ever owned—and sure enough, there were a few that came from Scholastic. Because these juvenile books generally clock in at the novelette/novella length, I decided to review two, The Runaway Robot and Revolt on Alpha C. They both stood out in my memory as good reads, and were written by top-notch SF authors. While Robert Heinlein’s juveniles are among the best-known SF books written for youngsters, he was far from the only one of his contemporaries who wrote for a young audience.

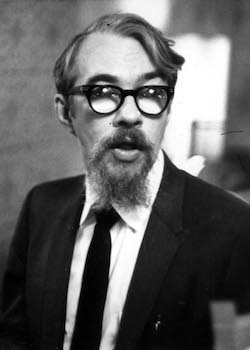

Lester Del Rey

There is some difference of opinion on Mr. Del Rey’s birth name, but Lester Del Rey is the name he was known by during his career in science fiction. He was born in 1915 and died in 1993. During the 1930s, he was a prolific author of short stories, which appeared in magazines including Astounding, Unknown and Weird Tales. Starting in the 1950s, he edited a number of science fiction magazines and anthologies, and wrote several works for young readers. In 1977, with his then-wife Judy-Lynn del Rey, he started the Del Rey Books imprint for Ballantine Books, which published both science fiction and fantasy. Later in his life, in recognition of his writing, editing, and impact on science fiction, he was selected by Science Fiction Writers of America as a SFWA Grand Master. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction mentions that Paul W. Fairman was an uncredited co-author of The Runaway Robot. I remember seeing Del Rey and his wife at one of the first conventions I attended—the distinctive difference in his and Judy-Lynn’s height, and their wit at panels, made them a memorable couple.

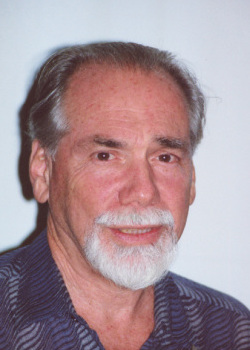

Robert Silverberg

Born in 1935, Mr. Silverberg is among the most prolific authors in the science fiction field—there have been several years in which he reportedly wrote over a million words per year. He sometimes authored multiple stories in a single magazine issue, using a variety of pseudonyms. He also partnered with author Randall Garrett, creator of the classic detective Lord Darcy, with some of their work appearing under the pseudonym Robert Randall. He has won four Hugo Awards in his career, including one for Most Promising New Author, two for novellas, and one for a novelette. He’s won the Nebula Award for two short stories, two novellas, one novel, and was selected as a SFWA Grand Master in 2005. Silverberg’s work often focuses on social issues more than the hard sciences, and as his career progressed, he was noted for paying more attention to characterization and stylistic issues than many of his peers. I don’t recall seeing him at the few WorldCons I have attended, which is no doubt the result of my own inattentiveness, as he has attended over sixty of them. In addition to science fiction, he has also written non-fiction, with much of it targeted at young readers. Revolt on Alpha C was his first novel.

Scholastic Books

The Scholastic Publishing Company (now called the Scholastic Corporation) was established in 1920. Their current mission is “[t]o encourage the intellectual and personal growth of all children, beginning with literacy.” In recent years, their output has expanded beyond books to include other media. They have also made some successful business decisions over the last several decades, becoming the American publisher for the Harry Potter books and publishing the Hunger Games series. There has been some criticism of the organization from religious groups for publishing books that deal with subjects that some find objectionable, such as the portrayal of magic and the inclusion of LGBTQ characters. Throughout their existence there has also been criticism that some of their output is more entertainment than educational, although from my perspective, anything that teaches young people to enjoy reading is a good thing.

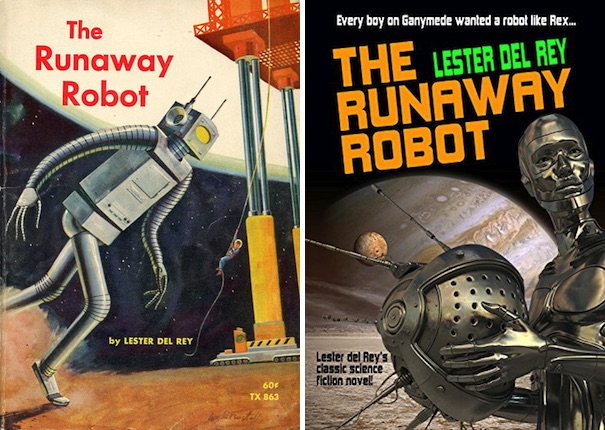

The Runaway Robot

The novel is written from the first-person viewpoint of Rex, the robot of the title. This allows the reader to quickly see that Rex is no ordinary robot—while he claims to lack human emotions, he clearly has some sort of electronic equivalents. Rex is a domestic companion robot, purchased to look over, entertain, and educate young Paul Simpson, something he has done faithfully since the boy was a toddler. The family lives on Ganymede, so the robot, among other things, makes sure Paul always wears his pressure suit outside.

Paul’s father announces the family will be going back to Earth, traveling on a luxury liner, and Paul is initially delighted at the news, but his delight turns to horror when he finds it will be too expensive to ship Rex back to Earth. Paul accuses his father of “selling [Rex] down the river,” a clear reference to slavery, and far from the only time that analogy will appear in the book. Mr. Simpson sells Rex to a farmer, who wants him simply to perform labor (there are some sort of valuable crops raised on Ganymede, referred to at one point as fungus and at another point as herbs). Rex is unsuited to these duties, but when he asks his new owner if he can instead perform tasks he is more familiar with, he is rebuffed. Out of the cognitive dissonance he’s experiencing, Rex formulates an idea: he will run away so he can see Paul one more time before he leaves.

When Rex makes his way to the spaceport, he sees Paul leaving the space liner, and concludes that the boy will head toward one of the hideouts where they used to play. The two are reunited, and formulate a plan to travel to Earth together. Paul has his life savings along with him in cash, something that seems a bit improbable to a modern reader, and people in this future simply buy tickets and walk aboard spaceships, with no security, passports, or customs to deal with. The book also improbably describes “mad robots” as going on murderous rampages and being able to hypnotize and kidnap humans (of course, we now know from dealing with semi-intelligent devices ourselves that the most likely outcome of malfunctions is for the device to simply cease functioning and sit around like a lump). Paul and Rex travel to a spaceport, dodging the authorities, and Rex finds work loading cargo onto a tramp freighter, using this as a pretext while Paul stows away on the ship.

The captain of the ship proves to be an unreliable man, who doesn’t know whether he wants to help Paul and Rex or turn them over to the authorities. The freighter is stopping at Mars, so the two companions will have challenges to overcome before they reach their goal of getting to Earth. The remainder of the book follows them as they face these challenges, and shows that Rex—because of his unique programming, and the difficulties posed by the forced separation from his boy companion—has become something more than an unfeeling machine.

For its time, and despite the simplicity imposed by its juvenile format, The Runaway Robot is a pretty good meditation on what it means to be sentient, and what the implications of machine sentience might be. The book also makes the reader think about freedom and slavery, and is a warm tale of the improbable bond between a human boy and an intelligent machine.

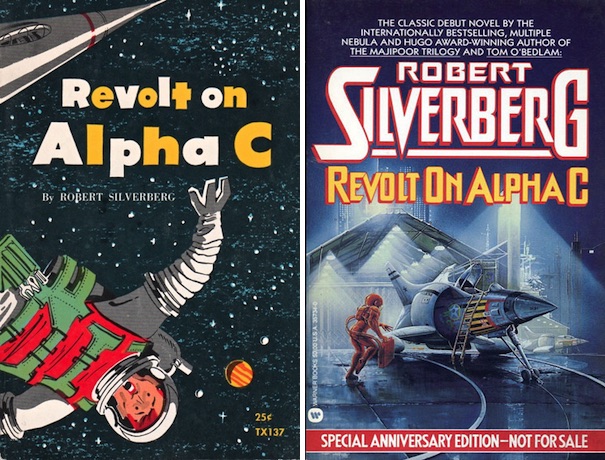

Revolt on Alpha C

Larry Stark is a cadet at the Space Patrol Academy, a second-generation military man on a post-graduation/pre-commissioning cruise aboard the patrol vessel Carden. He is traveling with his friend and classmate Harl Ellison, a burly Martian colonist (I didn’t pick up on the Tuckerization as a youngster, but it sure jumped out at me this time around!). They are on their way to the human colony on Alpha Centauri IV, a trip of only fifteen days thanks to the use of “overdrive.” Alpha C IV is a primitive world, with flora and fauna like that found on Earth in prehistoric times. That means dinosaurs figure into the story, something that definitely grabbed me as a young reader (and it seems to me that while dinosaurs are still quite popular today, they were very popular back in the mid-20th Century).

During the journey, Larry befriends an enlisted “tubemonkey” named Pat O’Hare, an Irishman with a fondness for music, who begins teaching him to play the guitar. This gives him a new perspective on the service, from the bottom of the chain of command rather than the top. When Carden suffers a propulsion casualty in mid-voyage, O’Hare is selected to repair it, and Larry to assist him. When O’Hare becomes untethered from the ship, Larry rescues him, strengthening the bond between the two. (This scene not only ended up on the cover of the book, but as one of the first times I had encountered a description of weightlessness, it stayed with me for years.)

Larry is a communications officer, and thus, upon arrival, is one of the first to hear that the colony is in revolt, and has declared itself the “Free World of Alpha C IV.” They find a city still loyal to Earth where they’re able to land, and Larry finds that his friend Harl—who, it turns out, was born on the rebellious Jupiter colony—has strong sympathies toward the rebels. Upon meeting some of the supporters of the rebellion, Larry discovers that they have some good points to support their position. He finds himself torn, especially when not only Harl, but also O’Hare, go over to the rebel side.

Larry is sent to pretend he is a rebel as well, but upon reporting back to his superiors, learns that they are considering destroying whole cities to bring the rebellion to an end. He has a decision to make: Will he remain loyal to the Space Patrol and Earth, or will he do the right thing, even if it means giving up his dreams of following in his father’s footsteps?

The story moves at a quick pace, and Larry’s ambivalence and indecision are well-depicted. The rebellion bears no small resemblance to the American Revolution, and for me as a young reader, the tale did a good job of illustrating the ambiguous moral issues involved in such a conflict. There are the inevitable anachronisms you encounter in a book over five decades old, but in general, it holds up fairly well. As a former communications officer, though, the loss of a key radio tube at one point shattered my suspension of disbelief. No military vessel would ever lack redundant communications systems, nor operate without spares for something as prone to failure as a vacuum tube (a modern youngster would probably be wondering what exactly a vacuum tube is, at this point in the story).

Final Thoughts

No one would call these two books literary fiction, nor could you argue that they represent the best output their authors produced, but they had a profound effect on me in my youth because they both featured young protagonists, and were written in clean, easy-to-follow prose. They served as bait on the hook that drew me into a lifetime of reading. And they featured interesting themes; the first raising questions about artificial intelligence, and the second exploring issues relating to politics and freedom.

And now I turn the floor over to you. Have you read either of these books, and if so, what did you think? And were there other books, from either the Scholastic Corporation or other sources, which attracted you as a young reader?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.