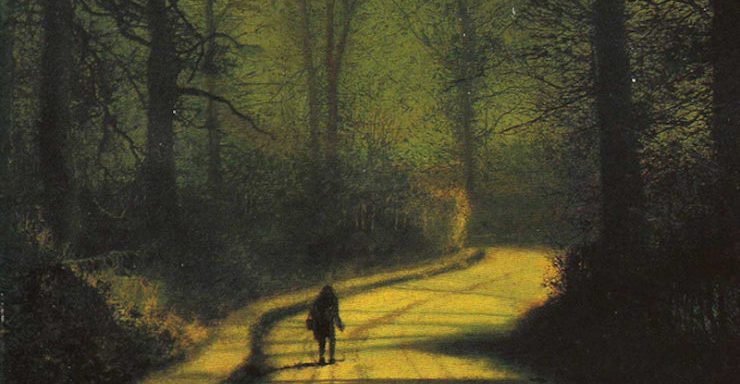

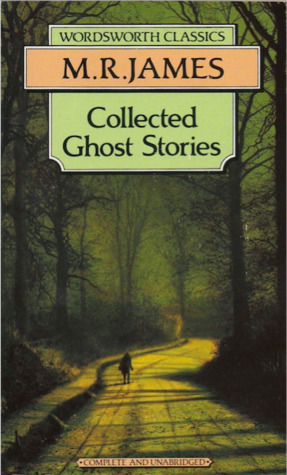

How have I missed M.R. James? I love ghost stories, I grew up reading horror, but somehow I’d never even read James’ most famous story, “Whistle and I’ll Come To You, My Lad”. But part of my original plan for TBR Stack was to work my way through the teetering towers of tomes that have made my apartment increasingly unlivable awesome, and I finally got to James! I’m not going in any particular order for this column (that way lies madness) but since I’d just read Colin Winnette’s brand new ghost book, The Job of the Wasp, I figured I’d keep the trend going. Luckily among my many stacks of books is the the 1992 Wordsworth Classics edition of James’ Collected Ghost Stories—a collection I greatly enjoyed.

Buy the Book

Collected Ghost Stories

We all agree that telling ghost stories at Christmas is one of the greatest holiday traditions of all time, right? Imagine my delight when I learned that M. R. James wrote many of his stories explicitly for that tradition, and that he and his circle at Cambridge gathered together to read the stories aloud to each other each Christmas Eve. Fittingly, it was his stories that brought that tradition back, when the BBC began airing A Ghost Story for Christmas in the 1970s, and then again when BBC Four brought the tradition back again in the mid-2000s. James is considered one of the preeminent English ghost story authors, publishing five books of ghost stories between the 1890s and the 1920s. His writing style, especially in the early stories, is a startling mixture of droll Britishness and violent description. For instance, this is the opening to 1904’s “Number 13”:

Among the towns of Jutland, Viborg justly holds a high place. It is the seat of a bishopric; it has a handsome but almost entirely new cathedral, a charming garden, a lake of great beauty, and many storks. Near it is Hald, accounted one of the prettiest things in Denmark; and hard by it is Finderup, where Marsk Stig murdered King Erik Glipping on St. Cecilia’s Day, in the year 1286. Fifty-six blows of square-headed iron maces were traced on Erik’s skull when his tomb was opened in the seventeenth century. But I am not writing a guide book.

I mean, what is that?

James’ tactic is deceptively simple. He begins with a fusty scholar or Lord, and uses his elevated language and droll humor (many, many golf jokes) to establish a sense of mundane if high class British life. Once his reader is settled and comfortable, James introduces an artifact that jolts the nature of reality. In this way his character’s lives are thrown into disorder by a single small object, rather than a more standard ghost story in which an unsuspecting person ends up trapped in a haunted place. James’ hauntings become micro-specific, centered in a flute or a slip of paper rather than infused into a house of a piece of land.

This is where I get tripped up on M.R. James.

What is a ghost story? Most of the ghost stories we grow up with are oral tradition, tales passed down around campfires and during slumber parties. “Ghost stories” are often so rooted in place: spirits lingering in houses where terrible things happened; stretches of road haunted by phantom hitchhikers; hotels with spectral guests; cemeteries that house a town’s dead.

And—to me at least—this is what makes a ghost story a ghost story.

Elizabeth Gaskell’s “The Old Nurse’s Tale,” Amelia B. Edward’s “The Phantom Coach,” and Charles Dickens’ “The Signal-man” (1852, 1864, and 1866 respectively) are all proper ghost stories. And Oscar Wilde had already lovingly satirized the ghost story trappings in his first published story, 1887’s “The Canterville Ghost.” Wilde trots out rattling chains, sudden moaning winds, bloodstains that won’t wash away, and clocks mournfully chiming 1:00 am, all in the service of a story about the spirit of Sir Simon, who soon realizes he’s no match for the brash Americans who’ve moved into his ancestral home.

The Shining is a ghost story. The Amityville Horror? Ghost story. Hell House? The Family Plot? Ringu? The Woman in Black? All ghost stories. “21st Century Ghost” and Poltergeist? Ghost story. “The Specialist’s Hat”? Ghost story. These are all stories in which a violent or traumatic thing happen in a contained site, and the soul or spirit or ectoplasmic impression remained in that site, repeating the actions that led to its death, or wreaking vengeance on any newcomer. Is The Babadook a ghost story? It Follows? No, since both of those are more a manifestation of a particular guilt or societal more: the titular Babadook isn’t the dead husband and father coming back, it’s a monster (and LGBTQIA icon) that seems to spring from the mother’s complex feelings about her child; It Follows features a shambling manifestation of sexual repression/STDs/AIDs. The Exorcist is not a ghost story—nor is The Exorcism of Emily Rose or The Exorcism of Molly Hartley or End of Days or Stigmata, for that matter, because those are all stories about vulnerable young people being possessed by demons who explicitly fit into a Christian framework.

I would argue that many of James’ stories aren’t actually ghost stories. More often, James used his career as a medieval scholar (he was a Don and Provost of Eton College and King’s College, Cambridge—Mark Gatiss made a documentary about James which you can watch here) to add historical details and religious facts that bring the stories to life, but which also render them more ‘tales of the occult’ than ‘ghost stories.’ His first book, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, played on his day job. Many of his stories are about specters that seem more like avenging demons/angels. “An Uncommon Prayer Book” and “A Warning to the Curious” are both about artifacts that are linked closely to British history, and in each case, disturbing those artifacts seems to call forth an avenging spirit of Britain. In “A Warning to the Curious” the spirit is specifically demanding that the artifact be replaced in its exact resting spot, with the implication being that England’s safety depends on it.

Then there are stories about occultists of various stripes—some living, some revenant—attacking more prosaic folks with spellworks and curses. In “The Ash Tree,” a woman who’s accused of witchcraft curses her accuser, and given how the story unfolds it seems that she did actually traffic in the dark arts. “The Casting of the Runes” follows a hapless academic who runs afoul of a cranky occultist, who then stalks the man, plants a written curse on him, and tracks his movements waiting for it to take effect. And “Lost Hearts” follows the treacherous life of a young orphan who is taken in by a distant cousin… a cousin who has previously cared for two other abandoned children, who each went mysteriously missing.

Meanwhile “The Mezzotint” and “A Haunted Doll’s House” are both about specific items that replay horrifying events for captive audiences—one a print that shifts and changes to depict a crime, the other literally a haunted doll’s house that serves as the setting for a murder.

James’ most famous story, “Whistle and I’ll Come For You My Lad”, hinges on a skeptic finding an antique brass whistle. TL;DR: he whistles, and something does, indeed, come for him. But here again—it isn’t the place that’s haunted. Sure, he finds the whistle in the ruins of an abbey, but he’s staying at a resort that is bounded on one side by the beach and on the other by a golf course. If the young man hadn’t found the whistle, and instead just explored the ruins, he would have been fine. Hell, he might have been okay if he just looked at the whistle and left it where he found it. It’s the act of disturbing the whistle from its place that seems to trigger the horror, because the whistle itself carries the haunting with it.

James seems to see life as trundling along down a narrow track, when a crack in reality allows other, darker elements to creep in. The idea of being “haunted” in James’ stories seems to be that even if you think there’s nothing wrong at first, this other, horrifying reality slides down around you and creates a wall between you and your fellow-men.

It’s interesting to me just how visceral and corporeal his specters are—hands that reach out of books or half-open doors, slithering, ill-defined shapes of either black (“A Warning to the Curious”) or an unsettling white (“Whistle and I’ll Come to You,” “The Uncommon Prayer-Book”), and hairy spider-like creatures that swarm over people’s faces and necks. Nobody gets away with just speaking to a ghost who then politely disappears, or feeling a general sense of unease, oh no: these specters will follow you home, sleep in the room with you, move your stuff around when you aren’t there, and then just jump on you. In multiple stories people are being followed by shadowy creatures—and other people can see them. Train conductors hold doors open for them, maids make up their beds, only for the living protagonists to turn and see nothing.

The other thing that got to me the more I read was that these ghosts don’t seem to follow any rules. They can cross water with no problem. They can inflict physical damage. They also sometimes ignore traditional Western ghost rules about making amends. More like Ringu or Ju-On, the mortal people can replace artifacts and apologize, but that doesn’t always mean that they’re absolved of their supernatural crime.

It’s possible I’ve been overthinking the fine lines of ghost stories. M.R. James’ stories rattled me in the best way, and I’ll definitely think twice before I remove ancient artifacts or dusty tomes the next time I’m exploring an archaic ruin.

Leah Schnelbach knows that as soon as this TBR Stack is defeated, another will rise in its place. Come give her reading suggestions on Twitter!