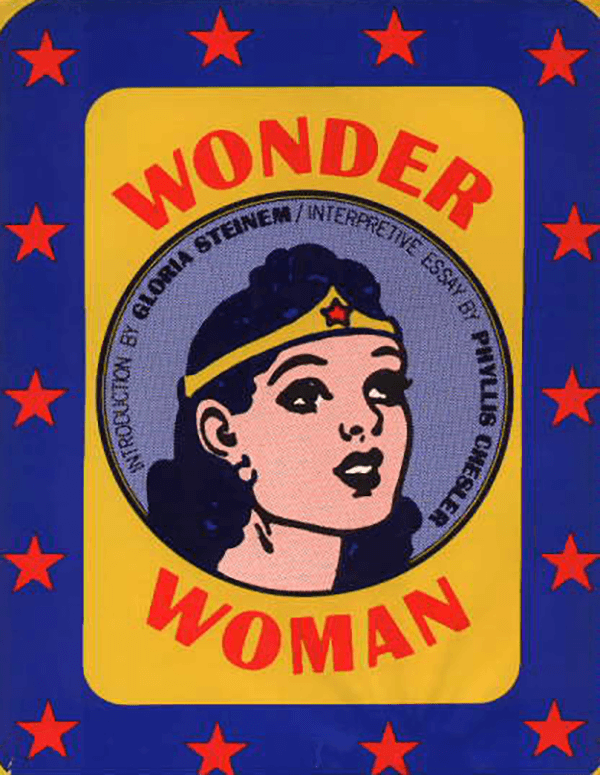

When I was a little kid, we bought a hardcover collection of classic Wonder Woman comics at a yard sale for a couple bucks. It was the fancy Ms. Magazine edition, with an introduction by Gloria Steinem, and it was full of these bonkers 1940s storylines about Nazis, Dr. Psycho, and Atomia, queen of the Atomic Kingdom.

I read that book until the covers fell apart, and then read it some more. I have a super vivid memory of being in bed sick, with a sore throat, and reading a scene where Wonder Woman gets captured. I thought to myself, “How is Wonder Woman going to escape from these bad guys when she has a sore throat?” And then I remembered that I was the one with the sore throat, not Wonder Woman.

I loved Doctor Who, growing up. I obsessed over Star Trek and Star Wars, and Tintin and Asterix. But the hero I identified with, deep down, was Wonder Woman.

Looking at those comics nowadays, I’m struck by things that went over my head when I read them as a kid. Like the the horrifying racism towards Japanese people and others. And the celebration of bondage pin-up art, which is a somewhat… let’s say, odd choice, for an empowering kids’ comic. These BDSM elements were mandated by Wonder Woman’s kink-loving creator, William Moulton Marston (and his uncredited co-creators, his wife Betty Holloway Marston, and their live-in spouse, Olive Byrne, who was Margaret Sanger’s niece).

What I saw, back then, was a hero who always laughed in the face of danger, in a good-hearted way rather than with a smirk. And a powerful woman who spent a lot of her time encouraging other women and girls to be heroes, to fight at her side. She came from a people who remembered being in chains, and she refused to be chained again. For all their kinky eroticism, the original Wonder Woman comics are also a story about slavery, and what comes after you win your freedom.

But most of all, the thing that made Wonder Woman irresistible to me, back then, was the way she felt like a fairytale hero and a conventional action hero, rolled into one brightly colored package.

In fact, there are a lot of fairytale elements in the early Wonder Woman comics, says Jess Nevins, author of The Evolution of the Costumed Avenger: The 4,000-Year History of the Superhero. (I was lucky enough to hang out with Nevins at Wiscon, while I was working on this article.) Wonder Woman frequently meets talking animals, rides around on a kangaroo, and runs along the rings of Saturn. Many Golden Age or Silver Age comics are gleefully weird or silly, but Golden Age Wonder Woman really embraces its fabulist roots.

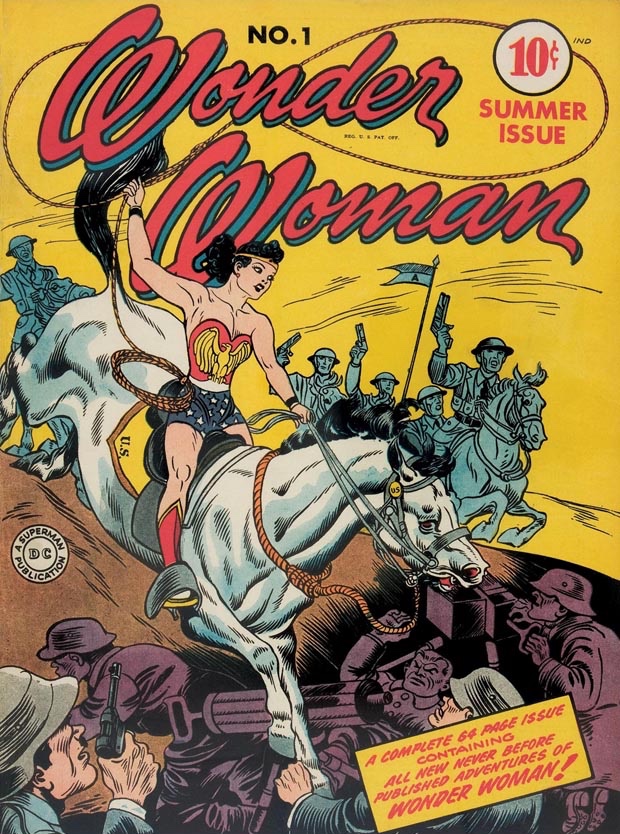

As part of this fairytale essence, Harry Peter’s artwork in the first Wonder Woman stories is a beautiful mixture of bright colors, grotesqueness, and glamour art. It’s strikingly bold, and not quite like any other comics art I’ve seen, either from the same era or later on. Even some of the most bizarre, over-the-top stuff in these comics feels like it’s of a piece with the extremes of classic fables.

Meanwhile, Wonder Woman is unique among superheroes, for a number of other reasons. She’s one of the earliest female comics heroes, and she’s not a distaff version of a male hero (like Batgirl or Supergirl). She’s based on ancient mythology, not science fiction or pulp adventure (in a different way than her contemporary Captain Marvel, aka Shazam). Most of all, while the early Superman and Batman are both angry vigilantes who constantly teach war profiteers and criminal syndicates a lesson, Wonder Woman is a joyful liberator and role model.

According to Nevins, while Batman and Superman come from the pulps, Wonder Woman is an entirely new character. She has her roots in stories from 400 years earlier, like Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, but there’s nothing like her in the pulps of the 1920s and 1930s.

And for all their problems and dated elements, those early Wonder Woman comics have a poetry that sticks in my mind all these years later. In Marston’s telling, the Amazons were tricked by Hercules and his men, who enslaved them until they were saved by the goddess Aphrodite. The bracelets that all the Amazons wear, including Wonder Woman, are a reminder that they have been subjugated before, and that this must never happen again. So when Wonder Woman does her famous trick of deflecting bullets with her bracelets, she’s using the symbol of remembrance of slavery to defend herself. But meanwhile, if any man chains her bracelets together, she loses her superpowers.

Jill Lepore, author of The Secret History of Wonder Woman, says this obsession with chains wasn’t just an excuse for Marston to feature lots of bondage fantasies (though that was a factor). Marston was heavily involved in the women’s suffrage movement of the 1910s, in which chains, and the breaking thereof, were a hugely important symbol.

But it’s also kind of awesome that one of Wonder Woman’s main superpowers comes from remembering her mothers’ legacy of enslavement. And she only gets to keep those powers if she bears the lessons of an enslaved people in mind. I don’t remember if Marston ever makes this clear, but it seems as though Wonder Woman is the only Amazon who doesn’t have firsthand memories of being a slave. She was raised by an army of badasses who had never let go of that memory, and yet she still has this boundless optimism and curiosity about the outside world. Like many fairytale heroes, Diana doesn’t always listen to the warnings of people who’ve already made their own mistakes.

(According to Lepore’s book, Wonder Woman’s bracelets are also based on heavy silver bracelets that Byrne used to wear, one of which was African and the other Mexican.)

Wonder Woman’s power being used against her is a motif in the Golden Age comics in other ways. Her lasso of truth, which has ill-defined mind-control powers in these early stories, works just as well on Diana as it does on anyone else. In one storyline, Dr. Psycho’s ex-wife uses Wonder Woman’s own lasso to force her to switch places and take the other woman’s place. Nobody could steal Superman’s strength or Batman’s skills (Kryptonite didn’t exist until later), but Wonder Woman’s powers are worthless unless she uses the full potency of her cleverness to outsmart her foes.

Speaking of Dr. Psycho, he’s a brilliantly creepy villain: a misogynistic genius who uses “ectoplasm” to create propaganda, in which the ghost of George Washington speaks against equal rights for women. (This all begins when Mars, the God of War, is upset that women are participating in the war effort, and his lackey, the Duke of Deception, recruits Dr. Psycho to stop it.) In one of the fable-inspired twists that fill these comics, Dr. Psycho’s power turns out to come from his wife, a “medium” whose psychic powers he’s harnessed and manipulated. This woman, too, Wonder Woman has to free from slavery, so she in turn can help to stop the enslavement of others.

As Marston’s health failed, his ideas got weirder and weirder. By the end of his run, the Amazons are constantly using mind-controlling “Venus girdles” to convert evil women to “submission to loving authority.” The themes of bondage and matriarchy get taken to an extreme, and the wings are falling off the invisible plane. But these weren’t the stories I read in that Ms. Magazine volume, and they’re not what I think of when I remember the early Wonder Woman comics.

I’ve never quite found another portrayal of the Amazon princess that captures everything I loved about those Golden Age stories. I caught reruns of the Lynda Carter-starring TV show, which consciously pays homage to the early stories (even taking place in World War II at first) but with a campy disco-era twist and that kind of genial blandness that a lot of 1970s TV has. Writer-artist George Perez’s 1980s reinvention of Wonder Woman gave her a decent supporting cast of mostly female characters, along with a stronger mythological focus. I’ve also really loved a lot of the Gail Simone/Aaron Lopresti comics, and Greg Rucka’s collaborations with various artists.

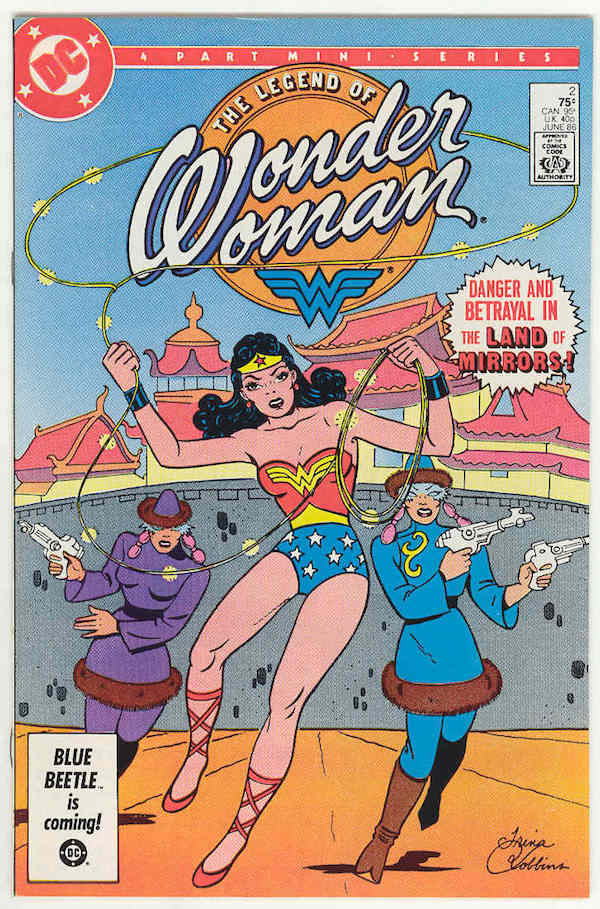

Best of all, though, Trina Robbins and Kurt Busiek collaborated on a four-issue tribute to the Marston-Peter era, called The Legend of Wonder Woman. It’s got Queen Atomia, loopy storylines, and all of the tropes of the Marston-Peter comics. (It’s never been reprinted since its first publication in 1986, but I found all the issues for a quarter each, and it looks like eBay has tons of copies.)

To some extent, Wonder Woman has changed with the times, the same as Batman and Superman. Sometimes, she’s more of a warrior, sometimes more of a diplomat. Her origin has been rewritten and the nature of her powers reshaped, until a lot of the original underpinnings of her character are harder to find. Of all the comics being published today, the one that most captures the innocence and exuberance of the very early Wonder Woman issues is probably Squirrel Girl, by writer Ryan North and artist Erica Henderson.

Last week, when a group of us were buying tickets for the new Wonder Woman movie, we asked my mother if she wanted to come along. She said yes, adding that Wonder Woman had been her “childhood hero”—something that I had never known about her. I asked my mom about this, and she explained that she read Wonder Woman comics constantly in the late 1940s. And, she added, “I used to fantasize a lot about being her.”

Wonder Woman isn’t just another superhero. She’s the woman my mother and I both grew up wanting to be. And I’m glad she’s getting her own movie, 100 years after the suffragette movement that inspired her.

Originally published May 2017.

Before writing fiction full-time, Charlie Jane Anders was for many years an editor of the extraordinarily popular science fiction and fantasy site io9.com. Her debut novel, the mainstream Choir Boy, won the 2006 Lambda Literary Award and was shortlisted for the Edmund White Award. Her Tor.com story “Six Months, Three Days” won the 2013 Hugo Award and was optioned for television. Her debut SFF novel All the Birds in the Sky won the 2016 Nebula Award in the Novel category and earned praise from, among others, Michael Chabon, Lev Grossman, and Karen Joy Fowler. Her new novel, The City in the Middle of the Night, publishes February 12th with Tor Books. She has also had fiction published by McSweeney’s, Lightspeed, and ZYZZYVA. Her journalism has appeared in Salon, the Wall Street Journal, Mother Jones, and many other outlets.

Before writing fiction full-time, Charlie Jane Anders was for many years an editor of the extraordinarily popular science fiction and fantasy site io9.com. Her debut novel, the mainstream Choir Boy, won the 2006 Lambda Literary Award and was shortlisted for the Edmund White Award. Her Tor.com story “Six Months, Three Days” won the 2013 Hugo Award and was optioned for television. Her debut SFF novel All the Birds in the Sky won the 2016 Nebula Award in the Novel category and earned praise from, among others, Michael Chabon, Lev Grossman, and Karen Joy Fowler. Her new novel, The City in the Middle of the Night, publishes February 12th with Tor Books. She has also had fiction published by McSweeney’s, Lightspeed, and ZYZZYVA. Her journalism has appeared in Salon, the Wall Street Journal, Mother Jones, and many other outlets.