In Which Arda’s Greatest Overachiever Steps Up and Melkor Is Released On Good Behavior

In the Chapter 6 of The Silmarillion, “Of Fëanor and the Unchaining of Melkor,” we’re given a short but impressive intro on the guy whose actions will upset the geopolitical foundations of Elvendom in the near future. We met him in the previous chapter and even got as far as the names of his kids, but now we’re taking a step back to look at his early life: the intensity of his birth, the tragedy of his mother, and the dilemmas of his father. Fëanor has so much to offer, and some of it will be to the betterment of all, and some…not so much. There is a bit of a call-back in his nature to the Ainulindalë, to the secret fire and to another who went often alone seeking greater power.

Speaking of whom, at the end of the chapter, Melkor will be released from his three-age prison sentence, which doesn’t bode well for anyone. So what does the most powerful of the Ilúvatar’s offspring brood about in prison? Certainly not rainbows and puppies.

Dramatis personæ of note:

- Míriel – Noldorin Elf, weaver, tragic mother

- Finwë – Noldorin Elf, king, husband to (it’s complicated)

- Fëanor – Noldor Elf extraordinaire, jack/master of all trades

- Melkor – Ex-Vala, ex-convict out on parole

- Manwë – King of the Valar, judge

Of Fëanor and the Unchaining of Melkor

This chapter is one part origin story, two parts character profile. It sets the stage for the deeds of (1) the most influential member of the Children of Ilúvatar, and (2) his (and their) bitterest foe. At first it seems odd to reintroduce these two in the same chapter, but they are as easy to compare as to contrast. It’s like a silvery coin flipped into the air. One side bears Melkor’s face, blackened but strangely still fair; the other, shinier side shows Fëanor’s face only slightly tarnished. How’s it going to land?

Fëanor is a complex character and he’s hard to sum up in few words, but if I had to describe him with just one, it would be rousing—for nothing about him is lazy, inactive, or complacent. He is a Roman candle blazing fiercely amidst every other Elf’s long, slow burn. An Elf of action and purpose, even when those things go wrong. Some readers respect him, some hate him. I think it’s okay to do both. He’s like that smart and politically outspoken person in your life who you usually disagree with but can’t help admire for their intelligence and conviction. Yet bullheadedness steers them toward trouble—and maybe the wrong side of history.

As with many nuanced characters, the story begins with a mother. Which is interesting, as maternal figures are markedly lacking, or conspicuously dead, throughout the legendarium. Tolkien himself lost his mother early in life, and it’s hard not to think this played a part in the lives of some of his more memorable characters.

Fëanor’s mother is Míriel, a weaver whose hands are more “skilled to fineness” than any among the Noldor. And up until the birth of her (in)famous son, the love between her and her husband, Finwë, King of the Noldor, is a deep and untroubled one, whatever may come.

We’re reminded that this is the Noontide of Valinor’s blissful days, and the same could be said for the Firstborn of the Children of Ilúvatar. If the long existence of the Elves was a single day, we’re already at midday—yes, this early in the book. As a race, they’ve still got a long time before Nightfall, but the point is they’ve already been around for a hell of a long time. How long? More than three unquantified “ages”—since Melkor’s three-age sentence was laid on him well after the Elves showed up. And an age isn’t exactly a blink-and-you-miss it span of time.

From The Lord of the Rings alone, we’re accustomed to talk about the “twilight” of the Elves. A fading, a diminishing. And the truth is, we’re going to start hearing about the start of that fading only a few chapters from now. But my point is, the Elves have already had a good and long run. We just don’t read about it all because it was, by comparison to everything coming, less eventful. The Silmarillion covers only the really big news.

So it’s in this Noontide that Finwë and Míriel have lived in joy and in prosperous times. The Noldor quarry, craft, and devise. And it is in the midst of such productivity that their baby is born. Now Finwë names him Curufinwë (which literally means something like “skillful son of Finwë”) but that’s not the name that sticks. His mother calls him Fëanor, and through the very process of bearing him, Míriel is “consumed in spirit and body,” and afterwards asks to be released “from the labour of living.”

Which…damn. Elves are immortal; they’re meant to live as long as Arda itself. There’s nothing about this in the handbook!

So, grieved over this heavy and very unprecedented request, Finwë turns to Manwë himself for help. But even the mighty King of the Valar cannot simply “magic” a person back to full hit points and mental health. Having no easy answer for his Noldor friend, Manwë recommends them to the Gardens of Lórien for care. Lórien is totally Valinor’s rehab center. And it’s where Estë, the Vala of healing and rest, also dwells. Perfect! There’s no better healthcare in Arda than Lórien. (It’s also the only game in town.)

For whatever reason, Finwë can’t remain there with her. Very limited visiting hours, one may suppose. And the whole situation sucks. On top of being separated from his wife, he knows Míriel will miss the first years of Fëanor’s young life—which any parent knows is an especially wonderful (if challenging) time. And of this, she says to him:

It is indeed unhappy, and I would weep, if I were not so weary. But hold me blameless in this, and in all that may come after.

It’s an especially sad and ominous moment. Míriel clearly senses or even knows something, about the power, possibility, and maybe precariousness of her son’s life. It is no throwaway name she gives him, for Fëanor means “spirit of fire.” And fire, as we’ve seen from the literal beginning, in both physical and metaphorical ways, can be a force of creative energy (the Flame Imperishable) or destructive evil (the Balrogs). Fëanor will show us more than a little of both.

But neither Estë nor Lórien can mend Míriel’s weary spirit. She has put too much of herself into Fëanor and has nothing left, not even basic nurturing. Her spirit departs, leaving her body “unwithered” but lifeless, and she drifts at last into the Halls of Mandos. This is the closest thing to true death an Elf can experience. If slain, they relinquish their bodies and go to Mandos and can even be rehoused in body after a great length of time. But Míriel’s not interested even in that. She’s not coming back. Does she fear what’s coming, fear association with it? “But hold me blameless…in all that may come after.” It is understandable, if abstract, to be physically spent—but why so sorrowful?

Breaking my own rule for just a moment, I’d like to draw in a quote from one of the History of Middle-earth books, The Peoples of Middle-earth, concerning this moment. Tolkien wrote:

The death of Míriel Þerindë—death of an ‘immortal’ Elda in the deathless land of Aman—was a matter of grave anxiety to the Valar, the first presage of the Shadow that was to fall on Valinor.

I mention this as a reminder that the Valar, for all their power, are not omnipotent gods. What has befallen this one Elf disturbs them. Interfering with Míriel’s choice to remain a disembodied spirit indefinitely was not something they were allowed to, or even could, do. Ilúvatar’s bylaws are quite clear. Moreover, her fate is a true symptom of the fact that even here in the bliss of Valinor…things are not quite normal. This is Arda Marred, remember…not, for example, Arda As Intended.

Of course, Finwë is especially grieved now. Not only is his wife gone—and his love for her was as real as it comes—but he had hoped for more children. In the great span of his life—or at least what his life could be—he is still quite young. Day after day Finwë sits with Míriel’s body beneath the silver willows of Lórien instead of with her spirit in the Halls of Mandos. We’re not told if this is because he would not be permitted to visit her actual spirit; he himself is both living and still incarnate. Visiting the Halls of Mandos doesn’t seem to be an option.

Plus wouldn’t it be awkward visiting your departed loved one with Mandos, the Doomsman of the Valar, watching over your shoulder? I’m just saying. That guys knows things. You don’t want him staring at you.

Finwë sits with her, not wanting to be separate from her. Moreover—and this is huge—we are told that “alone in all the Blessed Realm he was deprived of joy.” That means everyone else has been well and truly happy at this point, traipsing for untold years through this veritable heaven on Earth. But not Finwë, who for all intents and purposes is a single dad now. So he finally walks away from Míriel and throws himself into being the best father he can be. He showers all his love on little Fëanor. And he’s good at the new dad thing, at least at the start.

His son grows swiftly, “as if a secret fire were kindled within him, ” into a tall, raven-dark, and handsome Elf prince. Fëanor seems to inherit the raw talent of his mother, the stature and charisma of his father, and the cumulative skill of the entire Noldor people. He is arrogant and stubborn, listening very little to the wisdom of others, but his mind is keen. Not only are his hands possessed of greater proficiency than any other among the Children of Ilúvatar, but he is also the most “subtle in mind.”

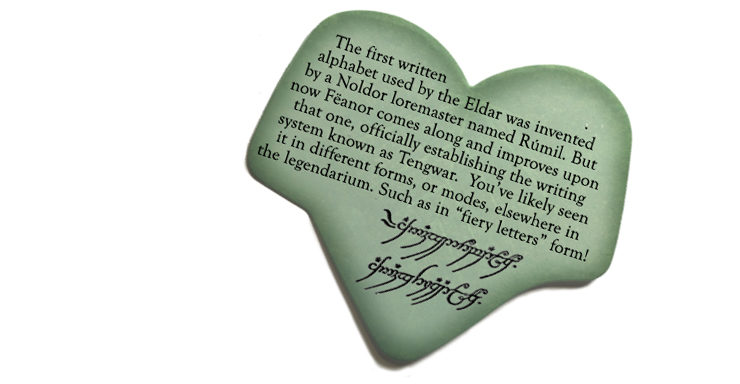

He’s even the inventor of the runic alphabet that the Eldar use from this point on. See, for all their love of speech, it’s only in only relative recency that an Elf came up with a written form of their language(s).

And as if it’s not enough to be the best at everything, Fëanor improves upon that, too. He’s like the Benjamin Franklin of the Elves; he seems to have discovered and/or invented everything of consequence. Only replace that whole key and kite thing with, say, a variety of light-emitting gemstones and a bunch of palantíri (yeah, the Seeing Stones were just a fun side project for him). “Seldom were the hands and mind of Fëanor at rest” is the point. The guy is a machine. But—and this is worrisome—he does his best work alone. As we’ve seen in the Ainulindalë, an uber-talented character going off alone isn’t always a good thing.

Anyway, from Fëanor’s hand come wonders the world has never seen. Gems that can capture and retain light are his speciality, and will lead us to those really important ones that show up in the next chapter. But given how productive he is even in his youth, there’s no way he didn’t at some point construct a diorama of the Gardens of Lórien or win every science fair. I bet on some bored afternoon as a small boy he threw together a silver-painted rocking horse model of Nahar, Oromë’s legendary steed, or made a clockwork Nessa doll that really dances.

At some point, Finwë finally gets out of the house and presumably stops smothering his son with attention. Remember, he’s the King of the Noldor and he still wants much more from life—and more children—and expects to have millennia to look forward to. So it’s just a matter of time, one supposed, before he meets and marries another Elf. This one is Indis, and is quite unlike Míriel. For one, she’s of the poetry-loving, Valar-devoted Vanyar, not a fellow Noldor. She also brings golden hair into a house of dark-haired men, and will pass those genes down to her granddaughter, Galadriel.

This remarrying thing is an absolutely unprecedented thing—Elves do not do this—and it “was not pleasing to Fëanor.” To say the least! And really, the whole situation is a metaphysical snafu. The death of Míriel—made of her own volition—and then the question of whether Finwë even can remarry vexes the Valar. Finwë and his family sure do make things complicated.

There is some fascinating behind-the-scenes discussion of this in Morgoth’s Ring, wherein all the Valar actually hold a council just to debate the matter. Legislation is proposed and made, Mandos gets involved, the late Míriel’s own spirit is consulted, and her explicit silence is deemed an approval, if nothing else. See, no Elf can have two spouses. If one is alive, the other can never be again. All Elves will be together in the end, whatever end, and if in death you reunite with more than one spouse, things are only going to be awkward. It’s all very crazy and fascinating and I recommend anyone check that book out (so much good stuff in there). But it’s beyond the scope of this Primer, so…moving on.

The main point is that all of this is really the result of Arda Marred. Melkor’s early meddling has poisoned the world in these less obvious ways. That the Valar brought the Eldar to Valinor and the light of the Two Trees is all well and good, but it’s also kind of just sweeping dirt under the rug. The dirt is still there, even if it’s beneath the surface. This is some of it.

And so a rift begins in the house of Finwë, with Fëanor spending more time away from his step-family, alone with his good looks and his mad skills. His much younger half-siblings, Fingolfin and Finarfin, eventually come onto the scene, and Fëanor isn’t the sort of big brother to show them the ropes. He’s got no time for anyone who isn’t Fëanor. With the exception of his father, whom he loves greatly. But when they hang out, there’s no way they talk about Indis and her sons.

When Fëanor himself comes of age, he is clearly Valinor’s most eligible bachelor. He’s the eldest son of the king, handsome and seething with raw talent and ambition. But Elves aren’t flighty about love, and though we know that Fëanor is proud, there is no reason to think he differs from his people in this. In fact, while he’s still quite young, he meets the daughter of a renowned Noldor smith from whom he’d learned “much of the making of things in metal and in stone.” I suppose, as a mentor. Which means that he falls for the boss’s daughter. Huh!

Her name is Nerdanel the Wise. Right away she sounds like the perfect foil for Fëanor. She becomes the cool head of their marriage, strong-willed like him, but far more patient. When his temper threatens to overtake him, Nerdanel alone can calm him. We are told that, unlike him, she desires to “understand minds rather than to master them.” When you have a heart-to-heart with Nerdanel, she wants to know your point of view first. If you try to have a heart-to-heart with Fëanor, he’ll Elfsplain to you how you’re wrong and how you should do what he says. The desire to influence or control others is not exactly an endearing trait, is it? Gosh, and where have we seen that before?

Still, let’s be clear. Aside from being a stubborn ass sometimes, Fëanor is no villain. Not yet. And certainly there’s nothing to suggest he’s a bad husband to Nerdanel. They are fire and ice; together they’re steamy. He’s passionate and headstrong, but he loves her, and I doubt he talks down to her as he does to others. Elves in Tolkien’s legendarium seem untroubled in familial relationships by the vices and petty desires that Men are plagued with. There’s no infidelity, no impropriety, no reality TV drama. With literally only the one exception we’ve just seen, they mate for life and are true to one another. They’re hardwired this way.

And so it is only Fëanor’s later deeds that will estrange these two. To the detriment of everyone. Once she’s not around him regularly, the dude is a loose cannon.

In any case, Fëanor and Nerdanel go on to have seven kids together—seven!—and throughout the long history of the Children of Ilúvatar, no other Elf parents will have this many. Did I mention he was an overachiever? Well, their kids are going to be movers and shakers in years to come, though they won’t quite make as indelible a mark as good ol’ dad. We learned in the previous chapter what their names are: Maedhros, Maglor, Celegorm, Caranthir, Curufin, Amrod, and Amros. Some of them inherit a measure of Nerdanel’s temperament, but most will possess Fëanor’s pride and tenacity. We’ll be able to see which ones take after him the most.

Speaking of pride, we come at last to Melkor. By the time his three-age sentence has finished, the three kindreds of the Eldar have long been ensconced in their posh homes in and around Valinor. The sons of Finwë and Indis are also already grown.

So the shackles come off, the doors of his prison are opened, and out into the Tree-lit realm Melkor is led to stand trial again—as was agreed. Before Manwë and all the Valar in their circle of thrones, he looks around and sees the Eldar gathered “at the feet of the Mighty.” These are the pesky Elves on whose account Melkor was laid low and locked up for so long? The ones who have benefited the most from his absence? Noted.

For their part, one has to assume that the Elves have been briefed on who Melkor is and what part he played before their coming. Some of them will remember the days at Cuiviénen, when rumors of a dark rider plagued them—and some of their kind were stolen away and never seen again. But they’ve never seen his evils with their own eyes. (The fate of those missing Elves and the existence of Orcs is known to no one yet, not the Valar, not Manwë. Project Orc is still on the downlow somewhere back on Middle-earth.) So to the first of the Elves, the world was beautiful even back then, but not entirely safe. Oromë had eventually come, and it all had worked out in the end. But plenty of Elves now exist who had never been to Middle-earth or seen its darkness. Fingolfin, Finarfin, Fëanor, and however many hundreds or thousands had been born since Ulmo ferried the Eldar across. Twice.

Heck, even their kids and Fëanor’s seven sons might be on the scene by the time Melkor is unshackled. Tolkien’s chronology is less clear before the start of solar years; the exposition in these early chapters isn’t presented in a perfectly linear fashion, either. My point is, the Eldar who were born into the bliss of Valinor are all the young “millennials”; they never knew the fears of the twilight days but also began their lives with greater education than their parents. The Eldar now have the Valar to learn from—often face to face!

So Melkor now sees the Elves standing there, buddy-buddy with the Valar. Which sickens him. The Valar are his own social and spiritual caste. Yet here, the Children freely dwell as willing subjects and friends and students, not as slaves and workers. That’s how things should have gone down in his mind. And he would have gotten away with it, too, if it weren’t for those meddling Valar! Especially Tulkas, that musclebound oaf… Oh yes, Melkor’s had three ages to daydream about vengeance against him and everyone else who’s wronged him. But now that he’s out, it’s the Eldar he hates most. They’re the ones who ratted him out and got him thrown in the slammer.

So yes, these Elves. He sees the shining gems that they’re all decked out with. Which is totally the Noldor’s doing. One wonders if Fëanor himself is present at this trial. His bling would be the brightest.

And what happened then…?

Well…in Valinor they say

That Melkor’s dark heart

Shrank three sizes that day!

All right, so that’s not how Tolkien put it. Even so, envy takes hold inside Melkor. He hides his loathing, for he “postponed his vengeance,” and he throws himself at the mercy of the court. He even requests of his brother, Manwë, that he might go forward now as “the least of the free people of Valinor,” and work now to help mend all troubles he’s caused. He makes no mention of the Orcs, that’s for damned sure. If they knew about those experiments, this trial wouldn’t end well for him.

So he sues for pardon. Interestingly, Nienna “aided his prayer,” meaning she actually speaks up on his behalf. She’s the only one who does. Seriously, Nienna! The Vala of grief, the Vala who has mourned and will forever mourn the marring of Arda by the defendant. She backs him up here, wanting Manwë to be merciful and grant Melkor pardon. And what about Mandos, who knows some things about the future? Mum’s the word.

At last, Manwë relents and pardons Melkor.

All right, so…why? To be fair, we readers know how long this book is, and that this is still just Chapter 6 of the Quenta Silmarillion. We can read the chapter titles from the Contents page and get the gist of things (and presumably Mandos gets to rifle and skim through the pages a bit). But the Valar? No. They don’t know, they can only hope. They might suspect that Melkor isn’t going to keep his word, they might worry and watch and wonder if this was the wisest choice.

Corey Olsen, the Tolkien Professor, has an excellent comparison to make about this choice. In one of his SilmFilm episodes, he likens Manwë’s choice to Aragorn’s at the end of The Fellowship of the Ring when the dying Boromir tells him the Halflings have been taken by the Orcs:

The decision to turn away, not pursue Frodo, but instead chase down Merry and Pippin’s captors—from a purely objective ends-oriented decision-making process—was a stupid decision…. I mean, yeah, Merry and Pippin are friends and stuff, but look, if Frodo fails because he doesn’t have guidance, the entire world is going to be destroyed. I like Merry and Pippin, too, but come on! The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few, right? Wisdom would suggest following Frodo is obviously the most shrewd thing for him to do if he wants to maximize the chances that the good guys win. Leaving Merry and Pippin to die in the hands of the orcs would clearly be a wrong thing to do. He has the power to help them…. Morally, he can’t leave them them to die. And Aragorn takes this as an indication that it’s therefore the right thing to do. This is his sign that he’s not supposed to follow Frodo now…. I’m not going to think about what is the wisest, shrewdest thing. Instead I’m going to follow what is right even when it looks like it’s the wrong thing….

It’s not that [Manwë is] stupid, it’s not that he’s foolish in the sense of he doesn’t think of these things, or acts rashly without thinking. It’s that he thinks and considers and yet chooses to show pity, chooses to show mercy, chooses to give the benefit of the doubt, and to follow hope instead of wisdom.

I think most of the Valar—even Nienna, Melkor’s ad hoc defense attorney—knows this is a big gamble and that they’ll probably regret it. But they are the offspring of the thoughts of Ilúvatar, the one whose mercy has been witnessed before. And so Manwë knows this is the right thing to do: to give Melkor one last pass, on the off-chance that Melkor turns over a new leaf. The only condition is that Melkor must remain in the city of Valmar, and not roam all of Valinor or, worse, all of Arda. He probably has to periodically check in with a probation officer and show that he’s not trying to take over the world again. The Valar want to keep an eye on him.

And Melkor plays the part of a penitent ex-Vala well. Three ages in the fastness of Mandos hasn’t changed the fact that he’s a “liar without shame.” He is good at seeming benevolent with his “words and deeds” and his many helpful pointers actually benefit both the Elves and the Valar. He might be evil, but he’s still a master of many things. He has been, since the Timeless Halls, the most talented at everything. Most talented of his peers…sounds familiar again, right? It’s downright Fëanorian, innit?

Manwë is fooled by his good behavior. He wants to believe that his brother might actually be…well, cured. Part of Manwë’s blindness is his own humility. He lacks the ego that drives Melkor. An he simply doesn’t understand evil. Of course, there are two among the Valar who aren’t fooled: Ulmo—hard to pull a fast one on him! And Tulkas—who just thinks Melkor is cruisin’ for a bruisin’ at all times. Yes, they observe Manwë’s ruling and don’t interfere. But Tulkas clenches his hands every time he passes Melkor on the street and, I’m thinking, makes a show of neck-cracking every chance he gets.

But it’s the Eldar that Melkor has in the crosshairs now. Hey may not be able to overthrow the Valar as he once dreamt, but he can mess up Ilúvatar’s precious Children. They’re vulnerable, and here he is right among them like a werewolf in…weresheep’s clothing? Maybe he can’t go after the Vanyar; those fair-haired, hippy-dippy, poetry-spouting bootlickers that stay too close to the Trees and to the Valar. More importantly, they’re too damned happy. And he won’t even bother with the Teleri. They’re nothing to him, those incurious, swan-loving Sea-elves.

But it’s the Eldar that Melkor has in the crosshairs now. Hey may not be able to overthrow the Valar as he once dreamt, but he can mess up Ilúvatar’s precious Children. They’re vulnerable, and here he is right among them like a werewolf in…weresheep’s clothing? Maybe he can’t go after the Vanyar; those fair-haired, hippy-dippy, poetry-spouting bootlickers that stay too close to the Trees and to the Valar. More importantly, they’re too damned happy. And he won’t even bother with the Teleri. They’re nothing to him, those incurious, swan-loving Sea-elves.

But the Noldor—ah, the Noldor! He can relate to them. They’re intrinsically crafty, they yearn to know what they do not already. And more importantly, they’re restless. Yes, he can work with all this! Best of all, a lot of them come to trust him. Well, except that one cocky gem-crafting Noldo. What’s his name again? Oh yes, Fëanor. He despises Melkor, and never accepts counsel from him, despite all his skill. Whatever, if Fëanor won’t be manipulated directly, perhaps Melkor can pull his strings indirectly.

So there we have it. By chapter’s end, we’ve got one important new character in play, an old one back in play, and this town ain’t big enough for the both of them. Somebody get the popcorn!

In the next installment, we’ll finally get eyes on Fëanor’s titular gems and we’ll try to figure out what sort of bonnet-dwelling bee Melkor is breeding in “Of the Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor.”

Top image: “The Secret Fire” by Deviant Art user noei1984

Jeff LaSala wonders what sort of screwy “secret fire” has kindled his son’s growth, because that kid won’t stop running and yet boycotts all sleep. Anyway, he once wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books.