In Which the Firstborn Come To, Melkor Gets His Comeuppance (For Now), and Elves Play Follow the Leader

“Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor” finally puts the Firstborn of the Children of Ilúvatar on the board. And there is, of course, much fuss and bother about these Elves, but there’s also some real trouble as Orcs are conceived in their image. We will also see the last of the land-smashing, Valar-based battles for thousands of years and the start of the great Elven trek. You know all that talk of sailing into the West in The Lord of the Rings? This is where that all begins.

Dramatis personæ of note:

- Melkor – Ex-Vala, maker of misery

- Yavanna – Vala, militant flower child

- Varda – Vala, stargazer, starmaker

- Tulkas – Vala, bruiser

- Mandos – Vala, total doomster

- Oromë – Vala, Elf-searching hunter

- Ingwë, Finwë, and Elwë – the first-named Elves!

Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor

Previously on The Silmarillion…

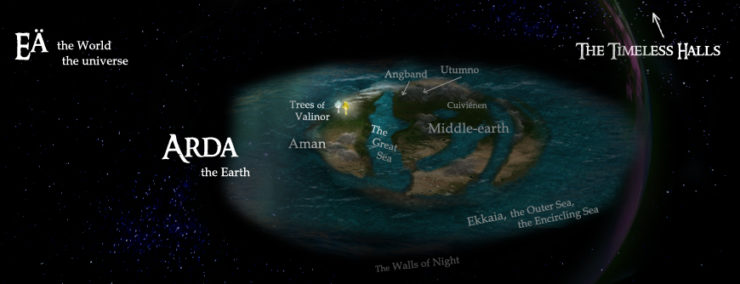

The Valar had established Valinor as the one place they could truly secure (*cough*—for now—*cough*) against the douchebaggery of Melkor. Yavanna, the Queen of the Earth, has every reason to just hang out there under the light of the Two Trees, into which she had put so much of herself. And throughout the fenced-in-by-mountains continent of Aman, she can nurture whatever she pleases. Surely she could just sit and be content, looking forward to the arrival of her Ents in peace.

But that’s not Yavanna. She’s a riled-up mama bear who’s already lost a cub to poachers and still has more to protect. She still grieves for the Spring of Arda that Melkor had ended so prematurely, and goes back often to the darkened lands of Middle-earth. When she does this, she even puts some of her favorite things—things that had already begun to grow while the Lamps were still around—into a kind of stasis simply to preserve them for better days.

And of course, Melkor himself has not exactly been idle. He’s cooking up terrible new things in his northern fortress of Utumno, monsters and “shapes of dread” that go out and trouble Middle-earth. Note that these are not altogether new creations. The narrative “camera eye” won’t be zooming in on any such beasts until much later, but this is likely when, for example, wargs and werewolves come about, warped and bred from natural wolves. See, Melkor can create nothing from whole cloth—he can only pervert things already made, or bind spirits into bestial bodies. Sort of like those Eagles from the last chapter, but far less savory. Less noble.

So Melkor’s keeping busy. One thing we’re explicitly told is that he keeps close around him his posse of Balrogs, those fiery, whip-wielding demons who are the oldest and most loyal of his subjects. He even has a second stronghold built, this one more to the west and closer to the shores of the sea. The new stronghold is called Angband, and Sauron is installed there to keep an . . . eye on things.

Meanwhile, Oromë and Yavanna continue to bring back reports to the other Valar on how things are looking on Middle-earth…

Not great, is how they’re looking. The Valar hold council over it. Yavanna votes for military action, reminding everyone that the Firstborn are bound to come soon…and c’mon, do they really want the Children of Ilúvatar to show up inside a dark, monster-haunted continent where Melkor is calling the shots? With a bold dig at her boss, she says:

Shall they walk in darkness while we have light? Shall they call Melkor lord while Manwë sits upon Taniquetil?

Yavanna is a firebrand! And why not? She’s pissed at Melkor; she wants his ass kicked. And at this point it sure doesn’t take much to win Tulkas to her side; he’s already fixing a knuckle sandwich with Melkor’s name on it. I’m thinking she probably had Tulkas at “Let’s kick some ass!” I mean, that’s got to be his favorite thing to think about.

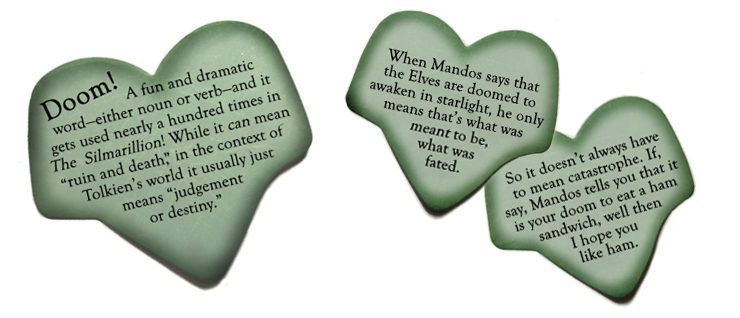

But über-calm Manwë, sitting up on his throne, simply turns to Mandos, the Doomsman of the Valar, and prompts him to speak up. Mandos, not one for small talk, doesn’t speak often, but when he does it’s meaningful. And so he states that yes, though the Children of Ilúvatar will indeed come soon,

it is doom that the Firstborn shall come in darkness, and shall look first upon the stars. Great light shall be for their waning. To Varda ever shall they call at need.

See that reference to “great light”? It’s important, but we can table that for now. That’s Mandos being coy, vaguebooking about something he’s not allowed to talk about yet. That’ll mean something later.

So it is while darkness reigns on Middle-earth that the Firstborn are supposed to come. And now that she’s been singled out, Varda—you know, the Vala who Melkor “feared…more than all others”—goes up and looks out upon Arda from the top of her tower on Taniquetil. She looks at the amount of starlight shining down from the dark of space, knowing that the Elves must awaken beneath it, and then decides, essentially, to increase the wattage. To turn the dial up to 11.

Varda makes more stars. Yeah, more. Like, a bunch. And how does she do it? Well, by gathering up some of that silver-glowing liquid she’d accumulated from the first and eldest of the Two Trees of Valinor. And with that potent substance she fashions new stars and even whole constellations. We’re told straight-up by our lofty-eyed narrator that this act is the “greatest of all the works of the Valar since their coming into Arda.”

Which—holy mackerel!—means it’s an even bigger deal than the Lamps or the Trees or all the shaping of the lands and seas to date. You just can’t say something like this lightly, and of course Tolkien seldom does.

Varda even caps off her project with the creation of the Valacirca, the Sickle of the Valar, a constellation of seven stars that a certain Ring-bearing hobbit will observe “swinging above the shoulders of Bree-hill” in the far distant future. This array of stars Varda places there as a direct “eff you” to Melkor, who she knows both desires and hates light. Varda is hardcore. If you’ve earned her scorn—for example, by eating her lunch in the office fridge—she’s not going to respond with some passive aggressive note. No, she’ll write out her wrath in the goddamned stars for all eternity. Varda doesn’t throw shade. She throws freakin’ starlight.

Varda is hardcore. If you’ve earned her scorn—for example, by eating her lunch in the office fridge—she’s not going to respond with some passive aggressive note. No, she’ll write out her wrath in the goddamned stars for all eternity. Varda doesn’t throw shade. She throws freakin’ starlight.

Now…whether Varda’s brightening of the starry sky actually serves as a catalyst for the “birth” of the Elves, or if it’s merely a complementary artistic expression on her part, we’re not explicitly told. But all the same, just as she’s finishing the last of her new stars, the Elves do awaken.

Sadly, the Valar are not there to witness it—they’re powerful but not omniscient—nor do they even known about the Elves until some years pass. Maybe it’s the fact that Melkor has made Middle-earth a gloomier place, but to me it has always seemed like Manwë—who commands the best vantage point in all of Arda up on his mountain—ought to have noticed the Elves first. We know from the Valaquenta that he could see into the seas and even into the caverns beneath the world, and that his winged spirit-servants brought him news from across Arda. But we’re also told:

yet some things were hidden even from the eyes of Manwë and the servants of Manwë, for where Melkor sat in his dark thought impenetrable shadows lay.

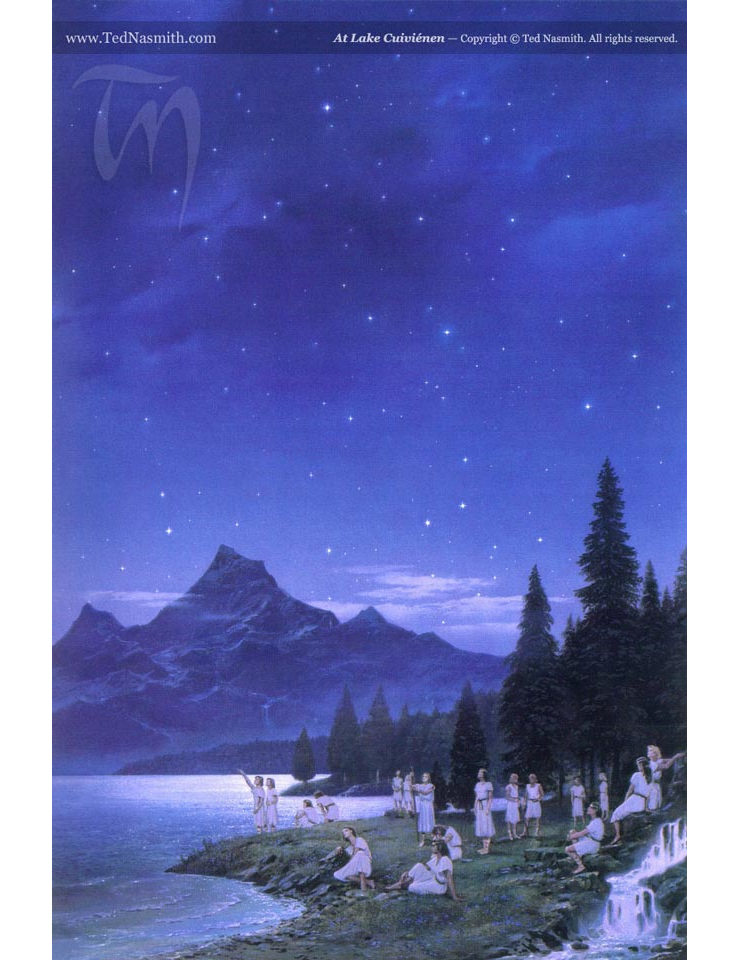

In any case, on the shores of a bay named Cuiviénen, a “starlit mere,” the first Elves awaken as if out of sleep. We’re not privy to knowing how they appeared—whether from thin air or from some divinely-hastened evolutionary process, or what. They are created beings, after all, placed there by Ilúvatar, right there in the world he’d charged the Valar with shaping. Cuiviénen is somewhere far in the east of Middle-earth, a gulf in one corner of an inland sea located near the mountains where one of the Lamps of the Valar had once been raised. But of course the Lamp itself is long gone now, and these Elves know nothing about it (until later).

This, then, is the long-awaited birth of the Firstborn of the Children of Ilúvatar! IT’S ABOUT TIME, RIGHT?!

As expected, the very first thing they see are Varda’s stars. And they love them, as they will one day love her, and the first sound they hear is water trickling down stones. That’s totally Ulmo’s music and the Elves will, in due time, come to hero worship him, too.

Now, I do have questions about this part of the story, too—questions Tolkien doesn’t answer for us, at least not in The Silmarillion. A deeper delving into extended Middle-earth lore, in the book The War of Jewels, shows that Tolkien toyed with the idea that the first Elves were “beneath the green sward, and awoke when they were full-grown.” Which makes me wonder: were they incubated in the earth as embryos and babies. Do the first-born of the Firstborn have belly buttons? Well, it doesn’t really matter—but it’s sure fun to think about.

Oh, and listen: we’re not explicitly told so, but because of the events of the previous chapter—wherein Manwë assured Yavanna that her thoughts from the Music would also awaken when the Firstborn did—presumably deep in the woods somewhere…a baby Treebeard is born. You’re welcome for that image. And maybe other Entings sprouted up, too? And Entwives! All things are still new.

And if he’s to be believed, Tom Bombadil is likely also around at this time, probably working on his first haiku about his blue jacket or his yellow boots. After all, he claimed to remember both “the first raindrop and the first acorn.” If he’s one of the Maiar, as many theorize, or simply some heretofore unknown variant of Ainu, then he’s probably been around since before the Lamps, too.

But, enough digression. Back to the Elves. For a very long time, they encounter no other creatures who talk—just animals and plants and maybe even those first Ents. And because of this the Elves call themselves the Quendi, “those who speak with voices.” Even in The Two Towers, Treebeard verifies just how chatty these first Elves were. He says:

Elves began it, of course, waking trees up and teaching them to speak and learning their tree-talk. They always wished to talk to everything, the old Elves did. But then the Great Darkness came, and they passed away over the Sea, or fled into far valleys, and hid themselves, and made songs about days that would never come again.

Yes, about that Darkness…

However long the Elves dwell in peace and wonder in these earliest of years, it is, to the woe of many, Melkor who finds them first. Sure, Yavanna has been coming and going, and Oromë especially has been roving about all the lands with his eyes peeled, but Melkor is the one with minions and spirits wandering throughout Middle-earth at this time. He’s the one with lookouts and spies. And so he finally discovers them, and Melkor is nothing if not the world’s greatest opportunist.

He doesn’t simply approach and introduce himself. No, that would be something an upstanding and dignified Vala would do. And maybe, as malevolent as he is, Melkor isn’t up to making nice with them, either. He despises the Elves for the favor they’re given, but he’ll despise them even more for the trouble they bring him.

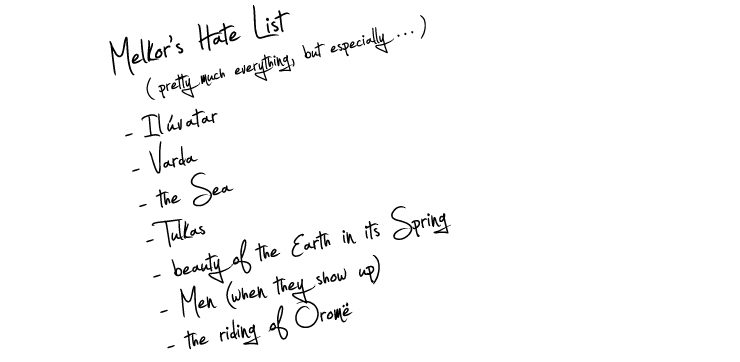

So instead of going among them personally, he stalks them and launches a smear campaign against the Valar. With his spies and “lying whispers” he starts a rumor among the Elves that a “dark Rider upon his wild horse” menaces their land from the darkness beyond. See, Melkor knows that Oromë is the Vala most likely to discover the Elves. Melkor hates and fears it. So much that… you know what? Oromë needs to go on that list.

So much does he hate Oromë that we’re told that at some point, probably long before now, Melkor actually raised up the Hithaeglir, the Towers of Mist (aka the famous Misty Mountains!) “to hinder the riding of Oromë.” I don’t know how a mountain range could really fence out a Vala, much less a sure-footed tracker like Oromë, but then again the Valar have done the same thing on their continent specifically to keep out Melkor. I think it’s mostly a testament to Melkor’s might; and for all we know, this is indeed what keeps Oromë from being the first to discover the Elves!

So much does he hate Oromë that we’re told that at some point, probably long before now, Melkor actually raised up the Hithaeglir, the Towers of Mist (aka the famous Misty Mountains!) “to hinder the riding of Oromë.” I don’t know how a mountain range could really fence out a Vala, much less a sure-footed tracker like Oromë, but then again the Valar have done the same thing on their continent specifically to keep out Melkor. I think it’s mostly a testament to Melkor’s might; and for all we know, this is indeed what keeps Oromë from being the first to discover the Elves!

Oromë could totally ruin Melkor’s opportunity. The dude is an epic-level ranger, pathfinder, and woodsman. He’s going to find the Elves eventually, and even though Melkor finds them first, that self-righteous monster-slaying do-gooder can still wreck his plans. So, using his spies, Melkor resorts to character assassination. He makes Oromë out to be a bogeyman, a monster to be feared so that the Elves will shun him when he comes. There’s a dreaded horseman—a black rider, if you will—who catches Elves alone in the wild and gobbles them up! Beware! When of course it’s Melkor who is doing this very thing. Elves that stray from their community in small numbers or alone are waylaid by his “shadows and evil spirits” and are never seen again. Worse, they are stolen away to his fortress of Utumno and thrown into his dungeons, where…

by slow arts of cruelty were corrupted and enslaved; and thus did Melkor breed the hideous race of the Orcs in envy and mockery of the Elves, of whom they were aftewards the bitterest foes.

Enter the Orcs, a perversion of Ilúvatar’s Children. The very act of their making is an expression of hate. Of utter contempt. There is so much to say about this part of the story, but franky most of it would also be mere speculation. Tolkien doesn’t go into detail on how the Orcs are made (and I, for one, am actually glad); we know only that they are rendered, at least initially, from Elven stock—and elsewhere in his writings it’s implied that in later years, Men, too, may have been subject to the same “slow arts of cruelty” and twisted into Orcs. We know from The Lord of the Rings that Saruman later breeds the foul Uruk-hai, possibly using Men in the process. In all such cases, the Orcs do propagate by the same manner as the Children, so there are males and females among them.

This Orc-spawning begins years before the Elves are discovered by the Valar. I feel like that’s an under-reported tragedy all its own. It’s implied that it’s not until much later that they learn that Orcs are linked to those Elves who went missing in the early days. Which makes some sense; the Orcs resemble nothing so much as bipedal monsters.

It’s even surmised by Tolkien himself—to be clear, outside of this book, in Morgoth’s Ring—that Orcs are more like “beasts of humanized shape (to mock Men and Elves) deliberately perverted/converted into a more close resemblance to Men.” They may be cunning enough that they can be taught to speak, or to parrot speech, but lack the souls of the Children of Ilúvatar. Though again, this level of detail does not exist in the published Silmarillion. One thing is made clear here, though. Orcs, from the moment of their incarnation as Orcs, loathe their master. They serve and fear Melkor first, as they one day will Sauron, with their wills bound to these Dark Lords, but they also most hate him, “the maker only of their misery.”

But back to the Elves. At last Oromë does discover them on the shores of Cuiviénen. There “in the quiet of the land under the stars” he first hears their singing, then rides closer and looks upon them for the first time. Oromë is thus the second of the mighty Ainur who now gets to see them in the flesh. And despite knowing about them for so long, he is still astonished. Here he is, a transcendent spirit of the Timeless Halls who can take any form of “majesty and dread” at will, yet he finds the Elves beautiful.

Neither he nor any of the Valar had any part in their making. They are such a mystery! As the long-awaited Children of Ilúvatar, they are still “something new and unforetold.” I like to imagine Oromë suddenly altering his physical appearance at this point, revising it now that he can see what the Firstborn actually look like. I mean, we know that up until this point that the Vala clothed themselves “like to the shapes of the kings and queens of the Children of Ilúvatar, as near as they could tell from that vision. “Ohh, their ears aren’t that pointy, are they? Yikes, these muttonchops need to go. And two eyes? Whoa, I was waaay off!”

So Oromë does approach them, and his horse spooks them: the Great Rider is come! Some Elves run and hide, believing the lies Melkor had sown. But the courageous among them hold their ground and quickly realize that he’s not some fiendish “shape out of darkness.” In fact, his horse glows silver in the starlight and it’s got golden hooves. Cool! This guy’s all right! Moreover, Oromë himself is a radiant being, though they can scarcely imagine what a Vala even is, at this point. The light of Aman, of Valinor, they see right there in his face. This is no evil being, and friendship is established. They had named themselves the Quendi, but Oromë calls them the Eldar, “the people of the stars.”

Oromë chills with for them for a while, delights in their company, then races back across the vast lands of Middle-earth, hops the sea (possibly high-fiving Ulmo as he does so), and returns to Valinor to tell the others. And though he might not know of the Orcs, Oromë knows about the rumors that scared the Elves, the “shadows that troubled Cuiviénen.” Understanding that Melkor is more of a problem now than ever, Oromë then returns to the Elves while the other Vala hold council and decide what to do.

After much contemplation and debate, Manwë declares at last that the Valar will gather and “deliver the Quendi from the shadow of Melkor.” And that means removing Melkor from the equation altogether! Tulkas presumably pumps his fist at this, while Yavanna might be rolling her eyes and sighing, “Finally.” Aulë is less excited at the prospect of another great battle, not because he doesn’t want to see Melkor’s ass handed to him (who among the Valar doesn’t?), but because he knows the Earth will again be badly damaged in the doing. And he’s not wrong. The Valar will go forth to war, unified, determined, assertive—and that means great upheaval. After the debacle of the Lamps they’d gone on the defensive. This time, with Valinor already fortified, they go full-on offense.

By the way, there’s nothing in the text that suggests any of the Valar stay behind for this. Tolkien has the tendency to pan back and speak only briefly of some of the most interesting of Arda’s conflicts, especially when it involves the Valar. But because he doesn’t say otherwise, the likes of Nessa, Nienna, Lórien, or even Mandos himself may well be participants in these huge battles! Which is awesome. I can’t help but wonder if fleet-footed Nessa’s got some ninja moves or if Mandos whispers “You’re doomed!” (or “Tonight you dine in my Halls…”) whenever he strikes down a foe. I bet Ulmo drowns his enemies with living waves and Yavanna goes all she-bear on hers. Or maybe she sprays poisonous thorns—

Sorry, this brings out the D&D fan in me.

Melkor meets the Valar with his own forces, probably with all his twisted beasts and evil Maiar and not so much with his new Orcs. He knows he can’t hide from this united front gathering against him. There are many times later in chapters to come where you may wonder, as I have, why the Valar simply let certain things happen, instead of rising up? Why don’t they just step in and throw down with the Dark Lord again, like they used to do, with great force? And the answer is: because every time Vala battles Vala, the world gets messed up. And in those later chapters Middle-earth will be full of squishable peoples all spread out—a conflict on this scale would decimate them, at the very least. If you remember, this was one reason the Valar retreated to Aman after the Lamps came down, and why they hadn’t searched too long for Melkor at that time. The Elves had not yet come, but they could have, and might have been buried in the resultant cataclysms of the battle with Melkor: the risk was simply too great.

But here, this one last time before the Elves start to wander beyond the place of their awakening, the Valar know precisely where they are. They can keep an eye on the Eldar, even as they stomp about and throw down mountains on each other or whatever it is they’re doing that wrecks the place. So they “set a guard over Cuiviénen,” sheltering the Elves not only from the conflict itself but from their awareness of it. Yes, the Elves can see mysterious pyrotechnics in the sky far to the north, and feel tremors in the earth, and even notice waters moving strangely like echoes of some far-off conflict, but they’re kept ignorant of what’s really going on.

The Great Sea that separates Middle-earth and Aman is widened as shorelines crumble, and the lands of the far north are scoured and broken, becoming desolate. It takes some doing, but the Valar do overcome Melkor’s forces and smash through the gates of both Utumno and Angband. They “unroof” his fortress, and down in Utumno’s “uttermost pit” Tulkas finally gets the fight he was craving. He takes on Melkor mano a mano, wrestling with him, almost certainly full-belly laughing the whole time.

Then “cast upon his face,” Melkor is bound head and foot, wrapped in a chain so hardcore that it gets its own name: Angainor. (But of course, this is Tolkien; he’ll name anything and make it sound awesome.) In fact, Aulë had made this chain exactly for this purpose. I assume it’s a +5 Chain of Binding and Spiritual Anchoring, because wrapped in this, Melkor isn’t going anywhere, nor can he assume some spirit form and slip away.

You can be sure that he is none too pleased about any of this, and we are made very aware who or what he blames fully for this outcome. No, not his inferior forces, nor his ever-growing list of transgressions against Arda and Ilúvatar. Not even the Valar:

Never did Melkor forget that this war was made for the sake of the Elves, and that they were the cause of his downfall.

Yeah, that’s fair. They scarcely know he even exists at this point, but apparently they’ve earned his wrath.

Melkor’s mightiest servants manage to flee and hide from the Valar—likely all the Balrogs and, most notably, Sauron. They peer under every rock and look under every bed, as it were, but simply cannot find him. Melkor himself is dragged over to Valinor and laid before the feet of Manwë in the Ring of Doom—which totally sounds like a quick name-grab from The Lord of the Rings. But it’s actually a circle of thrones, situated between the gates of the city of Valmar and the mound where the Two Tress are, and it’s where the Valar meet to discuss important things. It’s the conference room of the Valar!

Amazingly, after all that he’s done, Melkor seeks a pardon, but Manwë denies him and sentences him to three ages (no, we don’t know how long that is, but that’s no little stint in juvie)…

in the fastness of Mandos, whence none can escape, neither Vala, nor Elf, nor mortal Man. Vast and strong are those halls, and they were built in the west of the land of Aman.

At the end of this sentence, Melkor will be “tried anew.” But in the meantime, Arda will not be troubled by him any longer—yay! Only his many pernicious, albeit scattered minions will haunt Middle-earth. And no, that’s no small thing. The Valar are still worried about them, not for their sake but for the Children.

Their council meets again. What to do about the Elves, dwelling there “amid the deceits of the starlit dusk”? The Valar could leave them where they are, free to go where they will—and this is what Ulmo, himself a nomad who doesn’t settle down, votes for—or else gather them together in Valinor in order to protect them from the dangerous world Melkor had made of Middle-earth. They could come and live in the light of the Two Trees! How great would that be?

The Valar really do love these newfound Elves, the first of the Children, and they desperately wish to keep them safe. But for all their wisdom, they’re also clouded by their own affection. They wish to be near them, to teach them, to be as big brothers and sisters to these other smaller but more numerous offspring of Ilúvatar. Ulmo is outvoted.

It is decreed that the Valar will summon the Elves to come live with them in Valinor. And Mandos declares it in his ominous voice.

‘So it is doomed.’ From this summons came many woes that afterwards befell.

“Spoiler” alert: When you think about it, Mandos kind of is a walking spoiler alert. He knows things, and sometimes he even reveals them. But really, Tolkien is telling us right up front that this wasn’t the best decision the Valar could have made. Woe will come of it. The Valar are the great powers of good in this world, but they’re far from perfect. In this, at least, they’re like new parents making rookie mistakes, favoring fellowship and protection instead of observing the long view (which you’d think they’d be good at, being ageless and infinite).

When the Valar issue their summons, the Elves themselves are not quickly sold on the idea. They can’t conceive of the need to go to Valinor, or of the wonders to be found there. The world around them is already so dazzling. I mean, look at all those stars! Listen to that water! Moreover, what little they’d actually seen and heard of the Valar thus far had been “only in wrath as they went to war.” So forgive them if they’re a bit nervous about the prospect of traveling to some far-off magical fairyland. The solution, then, is that Oromë—the one Vala they’ve actually met and whose company they enjoy—will pick some Elves to be ambassadors, and ask them to come see Valinor with their own eyes. Then they can bring back word to the rest of their people, to let them make an informed decision.

It may just be a coincidence, but Oromë chooses three Elves whose names also have diaereses over the e. (I’m just sayin’.) These three amigos are Ingwë, Finwë, and Elwë, and they represent the first classifications that Tolkien uses for the Elves. It’s mostly just these three groupings in this chapter, which is merciful, because later Tolkien’s going to go nuts with divisions and subdivisions.

So who are these three again?

- Ingwë represents a small-ish kindred of blond-haired Elves called the Vanyar, aka the Fair Elves.

- Finwë represents a larger kindred called the Noldor, the Deep Elves, and they’re going to be the most storied (and uppity) of them all.

- Elwë represents the largest kindred called the Teleri (TELL-er-ee), who in time will be known as the Sea-elves.

These three ë-lords are led by Oromë back to Valinor—a long journey for non-Valar—and Holy Varda Lady of the Stars are they impressed! They’re “filled with awe by the glory and majesty” of Oromë’s peers, and they are positively gobsmacked by the light of the Trees, never mind the gardens and splendiferous estates where all these Maiar are living with their lieges.

So when Oromë returns the Big Three to the dim-by-comparison shores of Cuiviénen, they’re like, “Oh man, you all totally need to see these Trees. Heed the freakin’ summons! Let’s go West, young Elves!” Or probably something more dignified. And this, here, is the first and biggest schism of the Elves. Those who choose to head to Valinor—whether they succeed or not—are called the Eldar from here on out. If you remember, this was Oromë’s original name for all Elves, but now it’s just going to refer to those who heed the summons.

Those who choose to stay on Middle-earth, who refuse the summons, are now called the Avari, the Unwilling, and for the most part we’re not told what becomes of them. They don’t get involved in the First Age shenanigans to come, though in time, even as some wander westward, they do end up mingling with those Elves who did start the journey West but quit halfway there.

Of course, it’s no big deal for a Vala like Oromë to journey on his über-horse across the obstacle-ridden lands of Middle-earth by himself, but this time he’s leading three great hosts of Eldar. That takes some serious time, and there’s plenty of room for error, and danger, and everything is still new to them. The Elves may be in mint condition—stronger and “greater” than they’ll ever be, we’re told explicitly—but they have none of that aged wisdom we tend to associate with their race in later days. And their lore about the world is just getting started.

Oromë rides at the head of the exodus, so all these different groups lag behind. In fact, it’s the lagging, the “tarrying,” that really defines the Elven classifications to come. There is a lot of stop and go on this journey, and the Eldar themselves are in no hurry. Why should they be? They’re so delighted by the unfolding world around them—the Valar really have outdone themselves, despite Melkor’s marring.

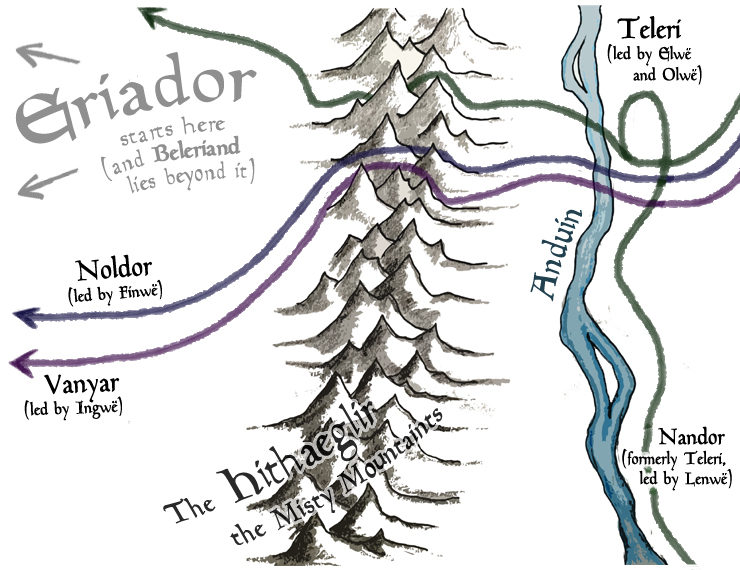

At some point they reach a mighty river running south, the widest they’ve ever seen. Later this river will be named Anduin the Great, and you may remember it from more familiar moments such as the death of Isildur, a pair of giant “talk to the hand” statues, or even a certain Fellowship’s own southward cruise. And just beyond this river is a tall and brooding mountain range, the aforementioned Misty Mountains (which, again, Melkor himself had “reared”).

And this is where we’re going to see “the first sundering of the Elves.” Let this serve as a basic and very not-to-scale, zoomed-in map of this point in time.

For the first two kindreds, the Vanyar and the Noldor, this is no biggie. They follow Oromë across the river and through the mountain passes. But the Teleri—again, the largest host of the Eldar—hang back for a while. Like, a long while, right there on the east side of the Anduin. And this means they’re left behind. Most of them are simply enamored of the river and wish to enjoy it. Others are actually afraid of the dark mountains looming in the distance—to be fair, they are “taller and more terrible” in these days. And now, without Oromë’s assuring presence, they have second thoughts about that whole going West thing.

A sizeable group of the Teleri actually call it quits right here. Becoming the Nandor, aka the Wood-elves, they turn south and follow the river without crossing it. Then they drift, by and large, out of the story for a long time. But not only will some of them later reunite with their Teleri friends, a lot of their descendants will become the Mirkwood Elves or the Galadhrim we know from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

The Teleri leader Elwë remains, though, and he’s eager to get a move on. He was really good friends with the Noldor leader, Finwë, and would like to catch up to him—and gosh darn it if he wouldn’t like to see those Two Trees in Valinor again. But his people are water-abiding by nature and it takes time to convince them to keep going, to make the crossing. Together with his brother, Olwë (we’ll hear more of him later), Elwë finally leads this massive host of procrastinating Elves across the river and the mountains. At this point, though, the Teleri have lost Oromë’s trail, and are falling waaaaaay behind the Vanya and the Noldor.

So, so much is going to come of that lag time, you don’t even know. (Unless you do.)

The Vanyar and the Noldor, meanwhile, have stayed close to Oromë. They journey across the topographical expanse of Eriador with its many rivers, mountains, vales, and forests. This is the region that will one day contain the Shire, Bree-land, the Trollshaws, Rivendell, and the Grey Havens. At its westernmost edge lies the Blue Mountains, Ered Luin. Then it’s on to Beleriand, which is that whole northwestern corner of Middle-earth between the Blue Mountains and the Great Sea, and it’s also the principal stage for the rest of The Silmarillion. At this point the map in the back of the book begins to mean something. (But not completely; we’ll first spend a few chapters in and around Valinor, for which is there no official map.)

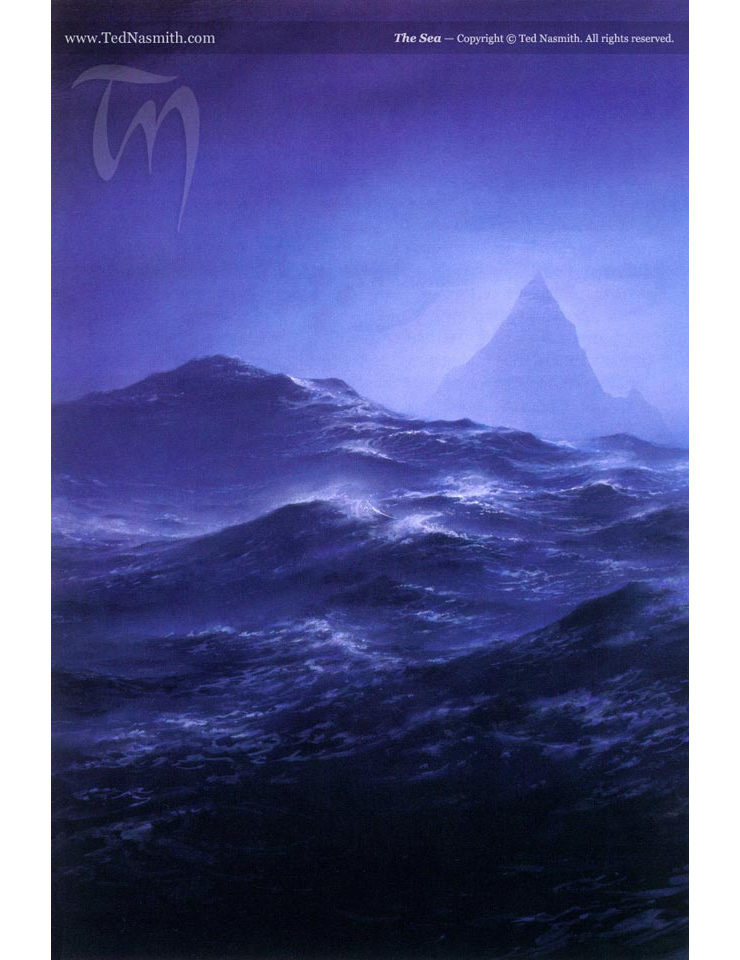

In any case, this is no quick jaunt across the miles, and immortal Elves are not known for hurrying. But eventually the Vanyar and the Noldor reach the west-facing coastline and follow it south a ways. They stop and stare out at the ocean, and just don’t know what to make of its hugeness. Some withdraw right back into the nearest woods, more than a little afraid of the sea.

But for the most part they just camp out, awaiting instructions from Oromë on how the heck they’re supposed to cross the Great Sea. To which Oromë seems to say, “Umm, riiiight.” After all, when the three ambassadors Ingwë, Finwë, and Elwë first came this way, Oromë probably just tucked them all into one little skiff, no big deal. But this time he’s got two greats hosts of Elves standing by, and it’s not like the Firstborn have learned how to make ships yet. So Oromë is all, “Brb.” And off he goes to find a solution. He hadn’t thought this far ahead.

In the next installment, we’ll see what it looks like when an Elf strays from the flock and gets snatched up by someone other than Melkor (“Of Thingol and Melian”), and we’ll meet more Elf royals than you can shake a scepter at (“Of Eldamar and the Princes of the Edalië”).

Top image from “Oromë discovers the Lords of the Elves” by Kip Rasmussen

Jeff LaSala can’t leave Middle-earth well enough alone. Tolkien fandom aside, he’s written a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, some cyberpunk stories, and some RPG books. And now works for Tor Books.