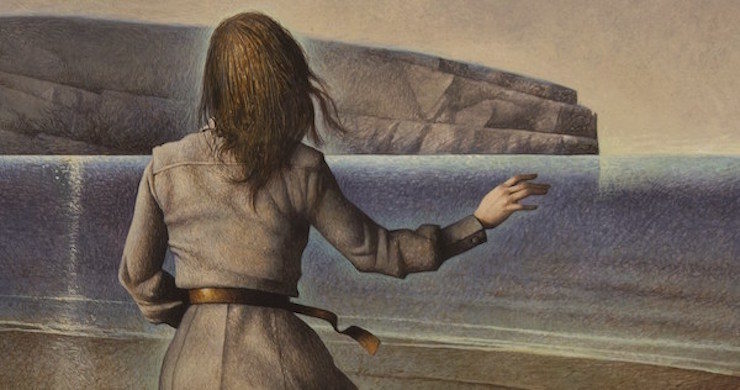

Ruthanna Emrys’s debut novel Winter Tide kicks off a new historical fantasy series, the Innsmouth Legacy. It follows Aphra Marsh, last survivor of the Innsmouth internment camps, working with the U.S. government that had imprisoned her people to prevent a magical war with the USSR. It’s about the found family she wraps around herself in a world she no longer recognizes. It’s about survival in the face of annihilation, kindness under the shadow of cruelty, and love as an antidote to hatred.

Aphra Marsh was first introduced in Ruthanna’s novelette “The Litany of Earth“, and we’re excited to share the first five chapters of her next journey with all of you!

Chapter 1

September 1948

Buy the Book

Winter Tide (The Innsmouth Legacy)

I shut the door of the old Victorian behind me, and the stuffy atmosphere closed in: overheated, dry, and redolent of mothballs. Remnants of cool mist clung to my skin, already transmuting to sweat. A whiff of old paper cut through the miasma. I focused on that familiar, beloved scent, and steadied myself.

Charlie, clearly untroubled by the warmth, took off his fedora and looked around the estate sale with a practiced eye. Choice artifacts adorned a table in the foyer—an antique globe and a few Egyptian-looking statues of uncertain vintage. The newly dead patriarch had been not only well off, but a professor emeritus of ancient history at the university. That combination was sufficient to draw us both away from the bookstore on a busy Saturday morning.

A woman approached us, frowning. She wore a floral dress and pearl necklace, but the black veil pinned over her curls marked her as part of the family hosting the sale. A daughter, perhaps? I was never good at estimating ages. Her eyebrows drew together as her gaze lingered on me. I smoothed my plain gray skirt—the color of storms and of mourning—then forced my hands still. She might not like the shape of my face or the pallor of my skin, but I wouldn’t give her any reason to complain about my composure. In the privacy of my chest, my heart beat faster. I tried to reason with it: beyond my chosen family, almost no one in San Francisco could know how to interpret my bulging eyes, thick neck, and receding hairline. She’d see an ugly woman, nothing more—the disquieted frown would likely be her worst reaction.

Charlie frowned fiercely back at her. Silence lingered while she twisted her strand of pearls between ringed fingers. At last he said: “I’m Charlie Day, and this is my assistant, Miss Aphra Marsh. We’re here to look at the books.”

“Oh!” She startled back to some semblance of her script. “Yes. Father was quite a collector. It’s mostly old academic junk. I don’t know that you’ll find anything interesting, but you’re certainly welcome to look. All the books and magazines are downstairs.” She jerked her head at the hall beyond the foyer.

Charlie led the way. The wooden stairs, hollow under our feet, shook with our steps. I held out an arm to help Charlie down, but he waved it off.

“Cheer up,” I murmured. “If she’s dismissing them as junk, she’ll likely sell cheap.”

“If she’s kept them in a damp basement, they will be junk.” He gripped the rail and descended, leaning a little to favor his right knee. I stared at his back, wondering how he could expect any part of this house to be damp.

The basement was not only dry, but hotter than the entry hall. A few books had been laid out on shelves; others remained piled in boxes and crates.

Charlie huffed. “Go ahead, Miss Marsh.”

Embarrassed, I picked up the nearest book—a thirty-year-old encyclopedia, Cartography to Curie, Pierre—and inhaled deeply. My pulse slowed. Over two years now since I’d gained my freedom, and above all else it was the scent and touch of printed paper that assured me of safety.

He laughed. “Let’s get to work. And hope she’s too busy sucking lemons to bother us before we’re ready to haggle.”

I immersed myself happily in the crates, laying aside promising volumes for Charlie’s approval while he started on the shelf. His store had no particular specialty, serving discerning antiquarians alongside anyone willing to pay three cents for a dime novel. The dead professor, I discovered, had maintained an unacademic taste for gothic bodice-rippers, and I amassed a stack of the most promising before moving on to the second box.

Here I found more predictable material. Most were histories and travelogues mere decades old. There were a few fraying works dating back to the 1600s—in languages I couldn’t read, but I set them aside anyway. Then, beneath a reprinted colonial cookbook, I found some. thing unexpected, but very much desired.

I probed the clothbound cover with long fingers, confirming that the volume would stand up to handling. I trailed them over the angular letters embossed on the spine, laid the book—perhaps two hundred years old, and clearly a copy of something much older—on the floor, and opened it. My Latin was far from fluent, but I could make out enough.

“Mr. Day, take a look at this.” I set the book on the table where he could examine it without squatting.

“Something for the back room?” he asked hopefully.

“I think so. But your Latin is better than mine.”

“De Anima Pluvia. The soul of the rain.” He turned the pages slowly, touching only the edges. “It looks like the author, at least, thought it belonged in our back room. We’ve had no luck trying…” He glanced at the stairs, confirmed them empty, lowered his voice anyway: “…to affect the weather, with every thing we already have. Do you think this’ll be any better?”

“I’ve seen it before. That was an older copy, and translated, but from what I can make out this is the real text, not a fake with the same title. It’s supposed to be one of the best works on the subject.”

He nodded, accepting my judgment. And didn’t ask where I’d seen it.

For two years now, Charlie had granted me access to his private collection in exchange for my tutelage in its use. And for two years, he’d never asked where I got my first training in the occult, how it had ended, or why a pale, ugly woman with bulging eyes lived in Japan-town with a family clearly not her own. I’d never offered to tell him.

After two years, I willingly called Charlie a friend. But I told him nothing of my life before I walked into his store, and he told me nothing of his. We shared the secrets we’d created together, and respected each other’s privacy for the rest. I didn’t even know whether he kept his own counsel out of pain or shame—or both, as I did.

But I did know that I couldn’t keep my own secrets forever—not if he kept studying magic at my side.

De Anima Pluvia, if we were able to make use of it, would allow a ritual that I’d long missed—and that, done right, would surely require me to reveal my nature. I tried to imagine his reaction. I didn’t think he would flee; he valued what I had to offer too much. But I feared his disgust. I would still trade my knowledge for his books, even without the camaraderie. I valued them too much to stop. But it would be a harder bargain, and I could taste the sting of it already.

The people of the water have always hidden, or tried—and suffered when we failed.

Spring 1942, or possibly 1943: My brother Caleb sits on the edge of Silas Bowen’s cot, while I keep watch by the cabin door. The older man thrashes and moans, but stills as Caleb tilts a bowl of water between his thin, protuberant lips. The water is alkaline and without salt, but seems to help. It’s been years since the camp guards allowed salt at our tables—with only the three of us left it’s a wonder Caleb was able to sneak water out of the cafeteria at all. It’s a wonder, in fact, that no one has checked Silas’s cabin since he stopped coming to meals over a week ago. The guards are distracted. We speculate, knowing the reason can’t be good.

Motors growl through the still desert air. Truck engines, unmuffled, and many of them—more than I’ve heard since they brought the last of Innsmouth’s straggling refugees to the camp fourteen years ago. Or perhaps thirteen years; denied a scrap of paper or coal to mark the walls, Caleb and I disagree on how long it’s been. My breath catches when I think of what this new incursion might bring. The sharp inhalation turns into a sharper cough, hacking that tears at my lungs until I double over in pain. Caleb stares, and his free hand clenches the ragged mattress.

Silas pats the bowl clumsily. “Aphra, child, drink.” Membranes spread between his fingers, but even this new growth is chapped and flaking.

“You need it,” I manage between coughs.

“What?” he rasps. “So I can die slowly enough for them to notice and kill me more painfully? Drink.”

Caleb brings me the bowl, and I haven’t the strength to refuse it.

Usually at estate sales, we were lucky to find even one book for the back room. So when Charlie called me over a few minutes later, it was a shock to hear him sounding out Enochian with his finger hovering above brittle, yellowed paper.

He broke off as I came near. “Good—maybe you can make this out better than I can. Damn thing’s too faded to read all the words, not that I know most of them.”

Dread warred with yearning as I approached the journal. In the years since the 1928 raid, a stolen diary could have made it from Innsmouth to San Francisco. If so, this would be the first trace of our old libraries that we’d managed to retrieve.

But as I examined it, I realized that we’d found something far stranger—if anything at all. I blinked with difficulty and swallowed, surprise making it easier to ignore the dry air.

“What is it?”

“I’m… not sure,” I said. “Or rather, I’m not sure it’s real. If it is what it appears… it purports to be the notes of a visiting Yith.”

“Borrowing a human body?” Charlie sounded doubtful, and I didn’t blame him.

“That’s usually the kind they wear, during humanity’s span on Earth. But when they end the exchange of bodies and cast their minds back to their own time, they try to destroy this kind of record.”

I’d told Charlie about the Yith, as I’d told him about all Earth’s species whose civilizations and extinctions they traversed aeons to document. For me it was vital knowledge—at my lowest, I found comfort remembering that humanity’s follies marked only a brief epoch in our world’s history. But for Charlie I suspected that those species, and the preservation of their memories in the Great Archive, might still be a half-mythical abstraction: something he tried to believe because I did and because it served as foundation to the magic that he so deeply desired. He’d never said otherwise, and I’d never been certain how to handle his unstated doubt.

“And one of them just happened to leave this journal behind?” He pursed his lips against the unsatisfying explanation.

“It seems unlikely,” I agreed, still trying to make out more of the text. If nothing else, the manuscript was the oldest thing we’d found that day. “I suspect it’s a hoax, albeit well-informed. Or the author could have fallen into delusion, or intended it as fiction from the start. It’s hard to tell.” The fact that I recognized most of the vocabulary, alone, suggested an entirely human origin.

“Should we buy it?” His eyes drifted back to the page. I suspected that he, like me, was reluctant to abandon anything in one of the old tongues.

“It’s beautiful. As long as we don’t expect to gain any great use from it…” Further examination confirmed my guess—the all-too-human author had dropped hints of cosmic secrets, but nothing that couldn’t be found in the Book of Eibon or some other common text. I suspected a real member of the great race would have been more discreet and less boastful—and made far more interesting errors of discretion. “If it were real, it would be priceless. Even the fake is old enough to be worth something. But our host doesn’t seem the sort to know its value either way.”

The door creaked, and Charlie jerked his hand from the journal. I flinched, imagining what my mother would have said if she’d heard me judge someone so in their own home. At least it was a young man in army uniform, and not the woman in the floral dress, who came down the stairs. He nodded briefly, then ignored us in favor of the vinyl albums boxed at the far end of the room. He muttered and exclaimed over their contents while I tried to regain my equilibrium. His uniform kept drawing my eye—making me brace, irrationally, against some punishment for my proximity to the books.

“I hope her father did,” said Charlie more quietly. It took me a moment to recapture the conversation: our host’s father must have seen some connection between the journal and his studies, or he wouldn’t have owned it. “I hope he got the best use he could out of the whole collection.”

“You wouldn’t want to waste it,” I agreed.

“No.” He bent, wincing, to rub his knee. “It makes you think. I’d hate to have someone go through my store, after I’m gone, and say, ‘He had no idea what he had.’ Especially if the Aeonists are right—no heaven where we can read every thing we missed and ask the authors what they meant.”

I shrugged uncomfortably. “I can offer you magic, but only in the universe we’ve got. Except perhaps for the Yith, immortality isn’t a part of it.”

Though he might not see it that way, when he learned more about who I was. I really couldn’t put it off much longer.

My brother was very young when they forbade us paper and ink. “The scollars,” Caleb wrote,

refuse my evry effort to beg or bargin entre. I have not yet resorted to steeling my way in, and in truth don’t beleev I have the stelth to do so nor the skill to pass unseen throu Miskatonic’s alarms. Sister deer, I am at a loss. I do not kno wether they forbid me do to knoing my natur or in ignorranse of it, and wether it is malis or uncaring dismissel. Pleaz rigt. Yors in deepest fondness.

“He should come home,” said Anna. “He should be with his family.” Mama Rei nodded in firm agreement.

“He is home. As close as he feels he can get, anyway.” I put down my fork, half-grateful for the distraction from the hot dog and egg mixture that clung vertiginously to my rice. The Kotos had somehow developed a taste for hot dogs in the camps, where we ate the same surplus rations for days at a time. To me they tasted of sand and fever-dry air.

Mama Rei shook her head. “Home is family, not a place. It does not help him to wander through his memories, begging books from people who do not care about him.”

I loved the Kotos, but sometimes there were things they didn’t understand. That brief moment of hope and fear at the estate sale, when I’d thought the journal might have been written in Innsmouth, had made Caleb’s quixotic quest seem even more urgent. “The books are family too. The only family we still have a chance to rescue.”

“Even if the books are at Miskatonic—” began Neko. Kevin tugged at her arm urgently before sinking back in his chair, quelled by a look from Mama Rei. It was an argument we’d gone through before.

“They didn’t take them in the raid. Not in front of us, and so far as Mr. Spector can determine from his records, they never went back for them. Anyone who’d have known enough to… scavenge… our libraries would have passed through Miskatonic, to sell the duplicates if nothing else.” Even books with the same title and text weren’t duplicates, truly, but few outsiders would care about the marginalia: family names, records of oaths, commentary from generations long since passed into the deep.

“Caleb’s a good man,” said Neko. She was perhaps the closest to him of us all, save myself. He had been just enough older to fascinate her, and her friendship had been a drop of water to cool his bitterness, the last few years before we gained our freedom together. “But a group of old professors like that—I’m sorry, but what they’ll see is a rude young man who can’t spell.”

“Nancy,” said Mama Rei. Neko ducked her head, subsiding under the rebuke of the given name she so disliked.

“They will, though,” put in Anna defiantly. “She’s not saying it to be mean. He should come back to us, and learn how ordinary people make friends, and take classes at the community center. Aphra is always talking about centuries and aeons—if Caleb takes a little time to learn how to spell, how to talk nicely to people who don’t trust him, the books will still be there.”

That much was true. And it was foolishness to imagine our books locked in Miskatonic’s vaults, impatient for freedom.

May 1942: It’s been years since the camp held more prisoners than guards, months since I’ve heard the shouts of young children or the chatter of real conversation. Over the past three days, it seems as if thousands of people have passed through the gates, shouting and crying and claiming rooms in long-empty cabins, and all I can think is: not again. I’ve done all my mourning, save for Silas and my brother. I can only dread getting to know these people, and then spending another decade watching children burn up in fever, adults killed for fighting back, or dying of the myriad things that drive them to fight.

When they switch from English, their language is unfamiliar: a rattle of vowels and hard consonants rather than the slow sibilants and gutturals of Enochian and its cousins.

Caleb and I retreat to Silas’s bedside, coming out only long enough to claim the cabin for our own. Most of the newcomers look at us strangely, but leave us alone.

The woman appears at the door holding a cup. Her people have been permitted packed bags, and this stoneware cup is the most beautiful made object that I’ve seen since 1928. I stare, forgetting to send her away. She, too, is a different thing—comfortably plump where we’ve worn away to bone, olive-skinned and narrow-eyed, confident in a way that reminds me achingly of our mother.

“I am Rei Koto,” she says. “I heard you coughing in the next room. It is not good to be sick, with so many crowded together and far from home. You should have tea.”

She hands the cup first to Caleb, who takes it automatically, expression stricken. I catch a whiff of the scent: warm and astringent and wet. It hints of places that are not desert. She starts to say something else, then glimpses the man in the bed. She stifles a gasp; her hand flies halfway to her mouth, then pulls back to her breastbone.

“Perhaps he should have tea also?” she asks doubtfully. Silas laughs, a bubbling gasp that sends her hand back to her mouth. Then she takes a breath and retrieves the confidence she entered with, and asks, not what he is, or what we are, but: “ You’ve been hiding in here. What do you need?”

Later I’ll learn about the war that triggered her family’s exile here, and crowded the camp once more with prisoners. I’ll learn that she brought us the tea five days after they separated her from her husband, and I’ll learn to call her my second mother though she’s a mere ten years older than me. I’ll be with her when she learns of her husband’s death.

Chapter 2

December 1948

Charlie, shivering beside me on the San Francisco beach, looked doubtfully at the clouds. “Do you think we can do this?”

“I’ve ignored Winter Tide for too many years.” Not precisely an answer. We’d done our best with De Anima Pluvia, but our biggest challenge had been finding a place to practice. The Tide itself was worth the risk of discovery, but any pattern of larger workings would draw notice. We’d managed a few small pushes to mist and rain, but couldn’t be certain we were capable of more.

“Ah, well. If it doesn’t work, I suppose it just means we’re not ready yet.” He wrapped his arms around his chest, and glanced at me. He wore a sweater to bulk out his slender frame and a hat pulled tightly over his sandy hair, but still shivered in what to me seemed a mild night. When I left the house, Mama Rei had insisted on a jacket, and I still wore it in deference to her sensibilities. California was having an unusually cold winter—but I’d last celebrated, many years ago, in the bitter chill of an Innsmouth December. I would have been happy, happier, with my skin naked to the salt spray and the wind.

“I suppose.” But with the stars hidden, there would be no glimpse of the infinite on this singularly long night. No chance to glean their wisdom. No chance to meditate on my future. No chance to confess my truths. I was desperate for this to work, and afraid that it would.

We walked down to the boundary of the waves, where the cool and giving sand turned hard and damp. Charlie’s night vision was poor, but he followed readily and crouched beside me, careful not to put too much weight on his knee. He winced only a little when a rivulet washed over his bare feet.

I glanced up and down the beach and satisfied myself that we were alone. At this time of night, at this time of year, it was a safe gamble that no one would join us.

I began tracing symbols in the sand with my finger. Charlie helped. I rarely had to correct him; by this point even he knew the basic sigils by touch. You must understand them as part of yourself, no more needing sight to make them do your bidding than you would to move your own legs.

Outward-facing spells had been harder for me, of late. To look at my own body and blood was easy enough, but the world did not invite close examination. Still, I forced my mind into the sand, into the salt and the water, into the clouds that sped above them. I felt Charlie’s strength flowing into my own, but the wind tore at my mind as it had not at my body, pressing me into my skull. I pushed back, gasping as I struggled to hold my course and my intentions for the night.

And it wasn’t working. The clouds were a distant shiver in my thoughts, nothing I could grasp or change. The wind was an indifferent opponent, fierce and strong. I fell back into my body with cheeks stung by salt.

Charlie still sat beside me, eyes closed in concentration. I touched him, and they flew open.

“It’s no good,” I said.

“Giving up so soon?”

I shivered, not with cold but with shame. As a child we had the arch-priests for this. Not a half-trained man of the air and me, dependent on distant memories and a few scavenged books. “I can’t get through the wind.”

He tilted his head back. “I know De Anima likes to talk about ‘the great war of the elements,’ but I’ve been wondering—should it really be through? When we practice other spells, at the store… I know these arts aren’t always terribly intuitive, but ‘through’ doesn’t seem right. When we’re working on the Inner Sea, or practicing healing, you always tell me that you can’t fight your own blood.”

I blinked, stared at him a long moment—at once proud of my student, and embarrassed at my own lapse. My eyes felt heavy, full of things I needed to see. “Right. Let’s find out where the wind takes us.”

I closed my eyes again, and rather than focusing on De Anima’s medieval metaphors, cast myself through the symbols and into the wind. This time I didn’t try to direct it, didn’t force on it my desires and expectations and memories. And I felt my mind lifted, tossed and twisted—whirled up into the misty tendrils of the clouds, and I could taste them and breathe them and wrap them around me, and I remembered that I had something to tell them.

I knelt on the strand, waves soaking my skirt, and gazed with pleasure and fear as the clouds spiraled, streaming away from the sky above us, and through that eye the starlight poured in.

“Oh,” said Charlie. And then, “What now?”

“Now,” I murmured, “we watch the universe. And tell stories, and seek signs, and share what has been hidden in our own lives.”

My last such holiday, as a child, had been a natural Tide: the sky clear without need for our intervention. They were supposed to be lucky, but my dreams, when at last I curled reluctantly to sleep beside the bonfire, had been of danger and dry air. Others, too, had seemed pensive and disturbed in the days following. Poor omens on the Tide might mean anything—a bad catch, or a boat-wrecking storm beyond the archpriests’ ability to gentle. No one had expected the soldiers, and the end of Tides for so many years to come.

That past, those losses, were the hardest things I must confess to night.

We lay back on the sand. Cold and firm, yielding slightly as I squirmed to make an indent for my head, it cradled my body and told me my shape. Wet grains clung together beneath my fingers. The stars filled my eyes with light of the same make: cold and firm. And past my feet, just out of reach, I heard the plash of waves and knew the ocean there, endlessly cold and strong and yielding, waiting for me.

I said it plainly, but quietly. “I am not a man of the air.”

Charlie jerked upright. “Truly.”

“Yes.”

I was about to say more when he spoke instead. I had not expected the admiration in his voice. “I suspected, but I hadn’t felt right to ask. You really are then—one of the great race of Yith.”

“What? No.” Now I pushed myself up on my elbows so I could see him more clearly. He looked confused, doubtful. “How could you believe I… no. You would know them if you met them; they have far more wisdom than me.”

“I thought…” He seemed to find some courage. “You appeared out of nowhere, living with a people obviously not your own. You found your way to my store, and my collection of books, and acted both singularly interested in and desperate for them. And you know so much, and you drop hints, occasionally, of greater familiarity in the distant past. And sometimes… forgive my saying so, but sometimes you seem entirely unfamiliar with this country, this world. I’d suppose shell shock, but that wouldn’t explain your knowledge. I didn’t want to pry, but after you told me about the Yith—how they exchange bodies with people through time—it seemed obvious that you must have somehow become trapped here, unable to use your art to return home. And that you hoped to regain that ability through our studies.”

I lay back on the wet sand and laughed. It was all so logical: a completely different self, a different life, a different desperation, so close and obvious that I could almost feel what I would have been as that other creature. My laughter turned to tears without my fully noticing the transition.

Charlie lifted his hand, but hesitated. I struggled to regain self-control. Finally I sat, avoiding his touch, and scooted myself closer to the waves. I dipped my palms and dashed salt water across my eyes, returning my tears to the sea.

“Not a Yith,” I said, somewhat more dignified. “Can’t you guess? Remember your Litany.”

“You sound like a Yith. All right.” His voice slowed, matching the chanting rhythm that I’d used to teach it, and that I’d taken in turn from my father. “This is the litany of the peoples of Earth. Before the first, there was blackness, and there was fire. The Earth cooled and life arose, struggling against the unremembering emptiness. First were the five-winged eldermost of Earth, faces of the Yith—”

“You can skip a few hundred million years in there.”

His breath huffed. “I’m only going to play guessing games if you are a Yith, damn it.”

I bowed my head. I liked his idea so well. I briefly entertained the thought of telling him he was right, and placing that beautiful untruth between us. But ultimately, the lie would serve no purpose beyond its sweetness. “Sixth are humans, the wildest of races, who share the world in three parts. The people of the rock, the K’n-yan, build first and most beautifully, but grow cruel and frightened and become the Mad Ones Under the Earth. The people of the air spread far and breed freely, and build the foundation for those who will supplant them. The people of the water are born in shadow on land, but what they build beneath the waves will live in glory till the dying sun burns away their last shelter.”

And after humans, the beetle-like ck’chk’ck, who like the eldermost would give over their bodies to the Yith and the endless task of preserving the Archives. And after them the Sareeav with their sculptures of glacier and magma. I could take this risk; even the worst consequences would matter little in the long run.

I raised my head. “I am of the water. I am ugly by your standards—no need to argue it—but the strangeness of my face is a sign of the metamorphosis I will one day undertake. I will live in glory beneath the waves, and die with the sun.”

His head was cocked now—listening, waiting, and holding his judgment checked. As good a reaction as I might expect.

“I will live in glory—but I will do so without my mother or my father, or any of the people who lived with me on land as a child. Someone lied about us, about what we did in our temples and on beaches such as this. The government believed them: when I was twelve they sent soldiers, and carried us away to the desert, and held us imprisoned there. So we stayed, and so we died, until they brought the Nikkei—the Japanese immigrants and their families—to the camps at the start of the war. I do not know, when the state released them, whether they had forgotten that my brother and I remained among their number, or whether they simply no longer cared.

“You thought that I hoped, through our studies, to return home. I have no such hope. Our studies, and my brother, are all that remain of my home, and all of it I can ever hope to have.”

“Ah.” The unclouded stars still burned overhead, but his gaze was on the water. At last he fell back on: “I am sorry for your loss.”

“It was a long time ago.”

He turned toward me. “How long were you imprisoned?”

That figure was not hard to call up. “Almost eighteen years.”

“Ah.” He sat silent again for a time. One can talk about things at the Tide that are otherwise kept obscure, but one cannot suddenly impart the knowledge of how to discuss great cruelty. It was hardly a piece of etiquette that I had learned myself, as a child.

“Aeonist teachings say that no race is clean of such ignorance or violence. When faced with the threat of such things, we should strive as the gods do to prevent them or put them off. But when faced with such things already past, we should recall the vastness of time, and know that even our worst pains are trivial at such a scale.”

His mouth twisted. “Does that help?”

I shrugged. “Sometimes. Sometimes I can’t help seeing our resistance and kindness, even the gods’ own efforts to hold back entropy, as trivial too. No one denies it, but we need the gods, and the kindness, to matter more anyway.”

We talked long that night, memory shading into philosophy and back into memory. I told him of the years in the camp, of the sessions with my parents where I first learned magic, of my brother’s quest, far away on the East Coast, to find what remained of our libraries. I told him, even, of my mother’s death, and the favor I had done for Ron Spector, the man who gave me its details.

I knew nothing of Charlie’s childhood or private life, and he told me nothing that night. Still, as much as I had learned of him in our months of study, I learned more through his responses now. Charlie was a brusque man, even uncivil sometimes. He was also an honest one, and more given to acting on his genuine affections than mouthing fine. sounding words. And he had been entirely patient with his curiosity until the moment I made my confession.

Now that I had shown my willingness to speak, his questions were thoughtful but not gentle. He would pull back if I refused, but otherwise ask things that drew out more truth—a deftness and appropriateness to the season that I might have expected from one of our priests, but not from even a promising neophyte.

At last, worn with honesty, we sat silent beneath the stars: a more comfortable silence than those we had started with, even if full of painful recollection.

After some time had passed, he asked quietly, “Are they out there?” He indicated the Pacific with a nod.

“Not in this ocean, save a few explorers. There are reasons that the spawning grounds were founded in Innsmouth—and in England before they moved. I am given to understand that the Pacific sea floor is not so hospitable as the Atlantic.”

This led to more academic questions, and tales of life in the water beyond the Litany’s gloss of dwelling in glory. Few details were granted to those of us on land, as children miss so many adult cares and plans despite living intimately alongside them. Still, I could speak of cities drawn upward from rock and silt, rich with warmth and texture and luminescence in lands beyond the reach of the sun. Of grimoires etched in stone or preserved by magic, of richly woven music, of jewelry wrought by expert metalworkers who had practiced their arts for millennia.

“Is that what you’ll do down there?” he asked. “Read books and shape gold for a million years?”

“Almost a billion. I might do those things. Or consider philosophy, or watch over any children who remain on land, or practice the magics that can only be done under the pressures of the deep. Charlie, I don’t even know what I’ll do in ten years, if I’m still alive. How can I guess what I’ll do when I’m grown?”

“Are we all children, on the land? I suppose we must seem like it—I can’t even think easily about such numbers.” He glanced back toward the mountains. “And such badly behaved children, too, with our wars and weapons.”

I grinned mirthlessly. “Be assured that the atomic bomb is not the worst thing this universe has produced. Though no one knows the precise timing of the people of the air’s passing, so it may be the worst thing that you produce, as a race.”

“I suppose it’s a comfort, to know that some part of humanity will keep going.”

“For a while,” I said.

“A billion years is a long while.”

I shrugged. “It depends on your perspective, I suppose.”

Chapter 3

December 1948–January 1949

Christmas followed close on Winter Tide. The Christian holiday first filled Charlie’s store with customers, then drew them all back into the seas of their families. Even he closed shop for the day and went to church services—awkwardly, I gathered, given his current beliefs. The Kotos, being Shinto, celebrated neither holiday, though Mama Rei and Neko surprised me after my post-Tide rest with a fish stew, studded with dried cranberries and salted almost to the traditional level for Innsmouth feast days.

To my relief, Charlie’s treatment of me didn’t change. The days between Christmas and New Year’s were quiet, and we spent most of our time studying in the back room. When we returned to the public area, we found that the gift-seeking customers had left it much in need of straightening. The pervasiveness of the foreign holiday had left me jittery: I fell to with a will, and spent happy hours sorting genre from genre and author from author.

Even the most ill-formed words, set to paper, are a great blessing. Still, I was not indiscriminate, and when I found a truly execrable passage in Flash Gordon and the Monsters of Mongo, I decided I’d enjoy hearing Charlie’s opinion. I drifted forward with one long finger marking my place, stopping occasionally to retrieve a book from the floor or straighten a row of spines. As I neared the counter, I heard Charlie’s raised voice:

“I don’t need you in here bothering my employee. Take whatever folders and files you’ve brought this time and get out.”

I toyed with the idea of letting Charlie drive him away. But as always, I could not feel safe turning my back.

I stepped out from my haven among the shelves. “It’s all right, Mr. Day. I’ll speak with him. Hello, Mr. Spector.”

He ducked his head. “Miss Marsh.” His eye caught on the book, and his lips quirked. I clutched it tighter, then forced my hands to relax. I let my finger slip from the page I’d meant to share.

A year and a half earlier, Ron Spector had walked into Charlie’s bookstore and asked for my help. The FBI had heard rumors of a local Aeonist congregation, doubted the group’s intentions—and wished to consult someone who wouldn’t condemn them merely for the names of their gods. For all his talk of better relations between the state and my people, and for all my acknowledgment that some people might use any faith to justify evil deeds, I refused to work for him. But I could not turn my back on the dangers of the state’s renewed interest in me—or resist the lure of meeting others who shared my religion.

It ended badly.

Afterwards Spector had sent sporadic notes from Washington, checking on my well-being. Perhaps it was some misguided sense of responsibility. I wrote back briefly, in minimal detail, not daring to ignore his missives entirely. He had not suggested any further tasks. There were, I feared, no other Aeonists in San Francisco, suspicious or otherwise. The rarity of my faith was the precise reason why he had approached me in the first place.

Over the past few months, these letters had dwindled, and I’d thought that he—or his masters—had given up the idea that I might be useful. I hadn’t been sure whether to welcome their apathy, or see it as an indication that my fellows were well and truly vanished from the land.

“You have something you wish to ask me. Ask it.” I braced myself, praying quietly for anything other than another ‘cult.’ I didn’t think I could bear another room of my fellow worshippers chanting familiar words and phrases that would turn out to be another mask for suicidal delusion. Or worse, for something more malicious than that self-proclaimed high priest’s desperate and contagious yearning for immortality.

And yet, if Spector told me of such a group, I didn’t think I could stay away.

He shuffled, glanced at Charlie. Charlie glared back.

“He stays,” I said. Then added: “He knows.”

Spector looked away, his skin reddening. I was not sorry to see his shame. He shook it off quickly enough. He took out a cigarette, tapped it on the counter, but didn’t light it. “I suppose you’ve heard about what’s happening with the Russians.”

One could hardly miss the papers—and I shared with the Kotos a fervent desire to see coming, early, the storms that might rile people against us. “Yes, the blockade in Berlin. Your allies are fickle.”

He shrugged. “They don’t see the world as we do. They expect every. one to think alike, act alike—and they’ll fight for it, if we let things get that far.”

In spite of myself, I shivered. The idea of another war… The World War—the first one—had taken so many of Innsmouth’s young men into the Army, returned many of them to sit blank-eyed and frightened on their porches—and perhaps triggered the paranoia of those whose libel brought the final raid on our town. The next war had stolen the Kotos from their lives and forced them to rebuild a community almost from scratch.

He continued. “ We’re working to stop them as best we can. There’s the new defense department, and the new agency for collecting foreign intelligence. I’m not involved with that directly”—he patted his suit pocket, as if I might forget the badge secreted there—“but we all work together, when we have to.”

“Of course,” I sighed.

“And the Russians have what, exactly, to do with Miss Marsh?” demanded Charlie.

“Nothing at all,” said Spector. “Except that someone’s gotten it into their heads that the Russians might use magic against us. And they’ve consulted with the FBI’s experts on—er—our domestic arts, to learn what they ought to do about it.”

I set the book down on the counter. “Mr. Spector, you don’t need me to tell you that magic makes a poor weapon. It’s not a tool for power, but for knowledge. And a limited tool, at that, unless you appreciate knowledge for its own sake. If your Russians are such scholars, you have little to fear from them.”

“We have little to fear from the magical arts that were legal in Inns-mouth.”

Charlie’s glare faltered. He knew the stories about what spells were forbidden, and why.

Spector pulled out a lighter and lit the cigarette. I stepped back discreetly. Charlie normally took his pipe outside in deference to my lungs, but I could hardly expect the same from others. Spector took a drag, and seemed fortified. “In short, they’re afraid that the Russians will learn how to force themselves into other people’s bodies—and use it not for personal immortality, but to take the place of our best scientists, our most influential politicians. The potential damage is staggering.”

“It is,” I said faintly. I thought about the bombs that had been dropped on Japan, and the potential for sabotage or theft in the secret places where they were kept. And I thought, too, about subtler things—words that could turn neighbor against neighbor, or government against citizen. “But I’m afraid I don’t have anything that can help you. To the best of my knowledge, there are no Deep settlements in the Pacific. If the Russians learned these arts, they didn’t learn them from us.” And while I could imagine one of our criminals deciding that switching with a Russian would put them sufficiently far from home to avoid capture, we would certainly have noticed if a bitter old man started speaking in a foreign tongue. Not to mention that most human versions of the art required direct contact, and Russian tourists didn’t generally visit Innsmouth.

“The Yith?” asked Charlie quietly.

“They don’t share their methods,” I said. “That’s why humanity’s versions of the spell are less powerful. But they all stem from imitations of visiting Yith. Russians could have learned that way as easily as any. one else; magic is no harder for men of the air than for us, merely less well known. And no, Mr. Spector, I know of no defense against body theft, nor any reliable way to detect it.”

He shook his head. “That’s not what I’m asking for—though I wouldn’t turn down a defense if you surprised me with one. The analysts believe they didn’t re-create the art on their own—but they may have sent someone to study at Miskatonic, some years back.”

While I stared, he went on, “I know you don’t like working for us directly. But I also know you have your own reasons for wanting to study that school’s records. We’ve persuaded them to accept a research delegation from the federal government. I would hope—that is, we wish to sponsor you to come along as a research assistant and language specialist. You’re more fluent in Enochian, and I suspect many of the other relevant languages, than anyone we can provide.”

I put a hand on the counter to steady myself. “Answer one question for me. Are you responsible for my brother’s inability to access the Miskatonic libraries, these past months?”

“No, of course not.” He shook his head vehemently. “Though we were aware of it. You must know that the, ah, activities of everyone released by Public Proclamation number 24 have been—kept abreast of—” Seeing my look, he hurried on. “But we’ve left him alone.” His lip quirked. “It might be better not to ask how we persuaded Miskatonic to offer our chosen scholars access, names unseen.”

“It might be better to tell me.” I crossed my arms. “Mr. Spector, I do want to see that library, very badly. But I will have no blood on my hands.”

He stepped back and held up his palms, a warding gesture echoed in a trail of smoke. “No blood, I promise.” He paused. “Miss Marsh, I wish you would give us some benefit of the doubt, however small.”

“I am willing to speak with you. To listen. It will take a long time for your masters to earn more.”

“The lady asked you a question,” Charlie said.

Spector sighed. “If you must know, there’s a partic ular dean with a penchant for carrying on with the maids. Not always entirely to their taste. His most recent girl works for us, and is a bit less easily cowed than the previous ones. He does us favors, sometimes, in exchange for keeping it all from his wife. And from the papers; Miskatonic prides itself on being a respectable school, after all.”

It was certainly as distasteful as he’d implied. I could hardly blame the woman for what she’d done—not given some of the favors Anna had won for us, when she was new to the camp and the soldiers grateful to suddenly find pretty, untainted girls under their charge. “Did you order her into that?”

“The girls get a certain amount of discretion in these things. You have to understand, she was already…” He trailed off, seeing something in my face, or Charlie’s. “She likes it better than her previous job.”

Not blood, then, on my hands. I swallowed and thought of the books. Spector was still good at making offers that I couldn’t find a way to ignore. And this time, I couldn’t refuse his offer and inquire on my own: without the state’s support, we’d remain as we were, with my brother hopelessly rattling Miskatonic’s gates.

If he needed us, I could at least set terms. “I won’t go alone. I’ll need my brother. And Mr. Day as well.” When Mr. Spector looked doubtful, I added, “His Enochian is coming along nicely,” though I suspected that was not where his questions lay.

April 1947: Much as I’d prefer to speak with Spector in my own territory, I meet him at the FBI’s local office. This conversation shames me, and I’d rather Charlie didn’t hear it.

The office is just outside Japantown, and shows signs of having lost staff in recent years. Spector, on loan from the East Coast, pulls chairs over to one of the empty desks with an apologetic shrug. Behind him, I see dusty file cabinets labeled in tiny, faded print.

“I visited the congregation,” I begin.

“I wondered if you might. If you’re willing to tell us about it, we could—” He stops himself. “Never mind. You found something you thought was important. Please go on.”

I try to guess what he didn’t say—was he thinking of offering payment? Should I be angry that he thought of it, or grateful that he thought better?

“They’re no threat to anyone else,” I start. “I want to make that clear. If you don’t believe me there’s no point in going on.”

“I believe you.” He sounds sincere enough. I wish I didn’t have to second-guess every word.

“They believe that they’re beloved of the gods, and that if one of them walks deep into the Pacific, unafraid and unflinching, Shub-Nigaroth will grant them immortality. Two of them went through the ritual before I got there. The others are convinced that their old friends are ‘living in glory under the waves,’ but I can assure you these people are entirely mortal—and the gods are not so attentive to human demands as they insist. Mildred Bergman, their priestess, is next. And—soon.”

“I’ll set something up,” he assures me. “ We’ll keep them safe. And Miss Marsh—I’ll do my damnedest to make sure no one treats them like the enemy.”

Neko came to me after the washing up, while I was working on a letter to Caleb.

“I want to go with you,” she said.

“Neko-chan, what for?” It took a moment for me to realize the source of my startlement: I still thought of her as the thirteen-year-old new come to the camp, and all too much like myself at the same age. But in fact she was nineteen, through with her schooling, more than ready to seek a husband or help support the household. She had been slower about both than Mama Rei would have wished, but that did not make her less an adult.

She twisted her hands together and stared at the floor. “I could go along as a secretary. You’ll need someone to take notes, and keep track of what you find.”

“I think the FBI already has secretaries.” I thought of the woman who’d paid for our entry with her own flesh, and shivered. I owed that woman something, though I doubted she would accept it even if I could figure out what it was.

“Your G-man would bring me along if you asked.”

“G-man?”

She shrugged it away. “Like in the movies. Please, Kappa-sama.”

I chose my words carefully, trying to explain something that had barely needed saying in Innsmouth. “Miskatonic University is not a nice place. The professors—they are old men, proud of their power, frightened of anyone who might threaten it. They care nothing for responsibilities or obligations outside the school. They are not evil, but nor are they good to be around unless one has a truly important reason.”

Her eyes slid toward the kitchen, where Mama Rei still remained sweeping. “You go out in the rain, without an umbrella or a coat. And you come home wet and happy.”

I smiled in spite of myself. “The water is good for me.”

“But it’s not just that.” She glanced at me, suddenly shy in a way that reminded me more reasonably of her younger self. “It’s a thing you couldn’t do, and now you can. Mama doesn’t understand, but—please forgive me, but when you were my age, you were still there, but I’m here and I don’t want to waste my freedom just taking dictation from old men—and there are plenty in San Francisco, too!”

“Old men who love power are everywhere, I’m afraid,” I admitted.

“I know. But I think that travel could be the rain, for me. And Mama will never let me try it, not if we had to pay, even if we could afford it.

But if I’m going along with you, if you asked, she wouldn’t argue. And then I would know. If it’s what I should be doing.”

Few enough of us get to do what we should be doing—assuming that such a thing even exists. I would not be the one to forbid her the rain.

We live in a world full of wonders and terrors, and so I cannot entirely fathom why my first aeroplane flight struck me so. Or perhaps I can: it was the first time I had left San Francisco since following the Kotos there. I felt vulnerable amid the cloying smoke and the crowd of well-to-do strangers at the airport. The women especially, with their makeup and store-bought dresses, watched us with unsympathetic eyes.

I dared not forget how we looked: a herd of odd and lame animals passing cautiously among predatory apes. Neko pressed close to me, and Charlie and Spector walked ahead to either side. I was grateful for their protection. Spector had a better gait for it, and a sturdier gaze. Still, I caught snickering whispers from a few who had picked out some Jewish aspect of his features, and I was grateful when at last we settled into our seats, away from the eyes and opinions of the susurrating crowd.

And then to go from that to the great machine gathering speed, leaping into the air and slipping through the clouds and into unexpected sun. Normally I prefer rain and fog, but somehow I felt safe, knowing that those things still caressed the city below—and behind, as we traveled swiftly onward. It was a perspective akin to meditating on the space between the stars, or the rise and fall of species over aeons. I saw more truly than ever that even a single day, on a single world, can contain both atrocity and kindness, storm-tossed seas and burning deserts. On such a world, lives may never touch and yet still give solace by the reminder that one’s own troubles are not universal.

I yearned to share my thoughts with Charlie, but he sat farthest from me, across the aisle. I considered trying to explain it to Neko, but even that would attract Spector’s attention. So I stared out the window as we soared over snow-brushed cyclopean mountain ranges, lifeless desert, and endless stretches of cleanly pressed farmland shadowed by dusk, before I fell asleep dreaming of the unfathomable lives of strangers.

The landing in Chicago was rough. The little plane shuddered down through a wild wind, bumping at last onto the tarmac while I considered whether it was worth drawing a diagram on the seat-back in front of me to try and calm the gale. Once we landed, I could see the softly pattering rain around us, barely blowing at an angle, and realized that the apparent storm had been an illusion of our speed, or of the plane’s own fragility.

As we milled in the terminal, waiting for our connection, I found myself oddly at ease: the predators all looked as tired as we were, and paid us little attention. I slumped on a chair, glanced over, and found Spector settled next to me. The skin below his eyes darkened with fatigue, but the eyes themselves flicked constantly. I realized that he, too, noticed every person who came within a few feet.

Of course, he caught me watching him as well, and smiled ruefully. “My apologies, Miss Marsh. Whenever I’m up late, my instincts start telling me I’m on watch. It doesn’t seem to do any harm, and it keeps me awake.”

“Ah.” Of course, he’d fought in the war. Most men had.

“European theater,” he added, giving me a considering look.

I nodded, quietly relieved that he’d never been in a position to kill any of the Kotos’ relatives. Or more likely, given his specialties, provide intelligence to those who did.

He leaned back and rubbed his eyes. “Miss Marsh—when we get there…” He hesitated.

I waited for him to go on. “Yes?”

“Just bear in mind that this kind of mission can accomplish more than one thing.”

Fatigued, I could just resist giving him an extremely impolitic look. “Mr. Spector, I can be discreet. But my talent is not in working ciphers.”

His eyes returned to their watchful rounds, then focused on me once more. “It can wait, I think.”

He looked uncomfortable enough that I was tempted to let it go. But I found myself equally uncomfortable allowing him to decide what I’d think urgent. ”I’m not fond of answerless riddles, either. I don’t want to walk into Miskatonic with my eyes closed, if there’s any alternative.” I added, lowering my voice, “I have good ears. Speak as softly as you like, but please tell me what I need to know.”

He hesitated another moment, and I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to push him further. But at last he relaxed and tensed at once, in the way of someone who’s made an unpleasant decision. “You know I was out of touch for a few months, before I contacted you.”

I nodded. “I assumed you realized there wasn’t much more I could do for your masters. They didn’t want you speaking with me?”

“We usually refer to them as Bureau leadership, but no, they didn’t. It wasn’t anything to do with you, though. I don’t know how much attention you pay to the news, but when Israel declared independence last May, our higher-ups started worrying about the Jews in service. I got a whole interrogation about whether I was planning to leave the country, whether I considered myself an Israeli citizen. A couple people quit over that, and one did emigrate. Said he might as well fight for someone who appreciated him… anyway, they took me off anything active for a while. Not officially, but they obviously wanted to keep an eye on me.”

“Oh.” I vaguely remembered reading about the new country, but I hadn’t made the connection somehow. His own people, half slaughtered in the war, had gone without a home for a significant chunk of the recent millennia. “So now they’ve decided to trust you again?” I almost asked why, but realized that it would be both rude and unnecessary.

He shrugged, gave a rueful smile. “ They’re giving me a chance, let’s say. Because I’m the one with a reputation for talking to the people they need.”

I frowned. “So you… need us to find something. For your career.”

He shook his head. “They aren’t stupid enough to encourage false alarms like that—and frankly, I’d rather go back to New York and work in my father’s deli than betray them that way. I’ve seen enough of the files to think there’s a real chance that something’s going on, but even if this turns out to be a false lead I don’t think they’ll hold it against me. Whatever we find, the work needs to look good—and it needs to be good. I need to show that what I do still matters, even when the threats they care about change.”

I considered, pushing through fatigue to see what he was driving at. “What you do—is talk to me. To us. To Aeonists and people of the water. You need to prove that we’re still useful.” And therefore, from the state’s perspective, that we still had a right to exist. I wrapped my arms against a chill that had little to do with the winter draft creeping through the plate windows.

He nodded. “I’m sorry, but yes. There are people higher up in the Bureau who’ve argued that Aeonists, as threat or resource, are no longer relevant. Like Nazis”—he didn’t quite keep the bitter irony from his voice—“a sociopolitical relic of the first half of the century, when we need to worry about the threats of the fifties.”

“Until 1928,” I said, “we thought we could survive by being ignored. We were wrong.”

“I don’t intend for you to be ignored,” he said firmly. “And I don’t believe that whole peoples and religions become irrelevant. It still matters that we can work together, and I plan to prove it.” He ducked his head, suddenly diffident. “And yes, I know it isn’t right for that to be necessary. For what it’s worth, I’m sorry.”

On the next flight, I slept particularly badly.

Chapter 4

Even as my mind hadn’t quite compassed Neko’s growth from nervous adolescent into restless young woman, so had my image of Caleb regressed, in his absence, to a child eager for adventure in the bogs, anxious lest I should receive the larger share of honeyed saltcake after dinner.

What met me at Logan Airport, after a long night of fitful sleep and exhausted transfers, was instead a gangling man in a suit that hung loosely over his long legs and arms. Like me, he still dressed in mourning grays. We embraced, then he held me at arms’ length.

“Aphra, you look wonderful. It’s good to see you.”

“And you.” He did not look entirely well. His hair remained ragged at the ends. I was minded that he’d been eating boardinghouse food of doubtful quality and stingy quantity, while Mama Rei tried her best to make up all our lost meals at once. (Except for the hot dogs, our mother would have entirely approved her table.) And where I had spent these past months in a set routine, with work for both mind and body, he had been shifting through Morecambe County, seeking in vain some way to influence Arkham’s academic elite.

His appearance could not have helped his quest. He shared with me the bulging eyes, the flat nose, the broad chin, and long fingers that marked our origin. We both fell on the paler end of our people’s range—unhealthily pallid to outsiders’ eyes. What he could not hide, he had made a shield of; when well-dressed passengers came too close, he loomed taller and thinner and they shied away from his gaze. I had always sought my mother’s dignity when I needed to appear sure or powerful. I wondered how much he remembered of our childhood, and of our parents’ strength.

I introduced him to Charlie and Spector. He shook hands with Neko, shyly. Then she laughed, tugged at his sleeve, and informed him that if he needed a suit he should have sent her his measurements. They bickered comfortably as we sought out the car and driver provided by Spector’s masters, more easy with each other than I yet felt with him.

It was over an hour’s drive to Miskatonic, and we passed it in fits of conversation that fell swiftly into silences. I could think of few topics that would not exclude either Charlie, Neko, or Caleb. All three were precious to me, but I knew them in different spheres. Nor did I wish to tell them of my worries where Spector might intrude with unwanted intimacy.

It was a small problem, and distracted me from what we were soon to encounter.

The Massachusetts winter was wet and cold, a shock of familiarity as we stepped out onto the great arching drive in front of the house of the mathematics dean. Snow deliquesced into slush beneath our feet, with a peculiar splash that I had not heard since I was twelve. Neko drew her jacket closer and shivered. I thought of cracked ice in the bog, and snowball fights. My eyes darted to Caleb, but I saw no humor in his stance, and decided against recalling our old pastimes in any active fashion. Besides, there was Spector.

A young negro woman met us at the door, took coats, showed us to a sitting room, offered tea. A clip pulled her hair tight at the nape of her neck, where it puffed out beneath her hat. Fire crackled in the hearth, exuding the smell of birch sap. I sat up straighter, and folded my hands in my lap. Caleb prowled the edges of the room, shuffling his hands from pocket to chest to the small of his back. The maid nodded at Spector and gave a half-smile, nothing like her otherwise deferential demeanor, before withdrawing.

A tentative throat- clearing in the doorway marked Dean Skinner’s belated entrance. Spector rose smoothly to meet him. Skinner hesitated before darting in to shake his hand.

“Well—welcome—that is, I didn’t entirely realize you were bringing such a—crowd.” He surveyed us with an air of grave doubt. “Are these your—scholars?”

“They are.” Spector took on the confident, knowing air with which he had first attempted to persuade me to his cause. “ These are our linguistic specialists, Miss Aphra Marsh and Mr. Caleb Marsh, and Miss Marsh’s student, Mr. Charles Day. And Miss Nancy Koto, our note- taker.”

“Ah. Yes. Marsh, you say.” He adjusted his glasses and peered at Caleb more closely. “Well, that does take one back. Not a name one hears much, these days. You are originally from Innsmouth, then?”

The question was directed to Caleb, but he only frowned in response. I drew myself up in my chair. “I am still from Innsmouth. However, I currently make my home in San Francisco.”

“Ah—yes—well. I’m sure some of the anthropology students will wish to inquire of you regarding Innsmouth’s famous—or infamous—folklore. It is still a topic of interest among those, ah, interested in esoterica.” He waved the matter aside before I could respond, and turned back to Spector. “I suppose you must know what you’re doing, hiring people with such a—distinct—background. But where on earth are we to put them all? You know that we’re always happy to support federal research, though of course we’d do better with more details about what you’re looking for. But you made no mention of, ah, students of the female persuasion. It certainly wouldn’t be proper to—that is—or—perhaps we could board them at the Hall School?”

“It’s almost an hour away,” said Caleb quietly. His hands were clenched at his side.

“Yes,” I said. “We’re here for the library, not the roads.”

Miskatonic’s ostensible sister school was not a well-kept partner like Radcliffe or Pembroke. My mother, never one to gossip, had spoken witheringly of the Miskatonic professors’ beliefs about female intellect. They held Hall at a well-chaperoned distance on the far side of King-sport, and it lived off the dregs of the more famous school’s materials and collections.

Dean Skinner glanced between us, blinking rapidly. “Well. Then I suppose we must—hmm.”

I considered suggesting that he and his wife might host us without impropriety. But it would have been cruel, and perilously close to a threat. When he was not so off-balance, the dean must be a formidable predator. And he would not be pleased at having been seen so vulnerable.

At last, his face lit. “Ah. Just the thing. Professor Trumbull has room in her house, I’m sure. She’s Miskatonic’s first lady professor, you know. Multidimensional geometry. Stunningly brilliant of course—although she—well—they do say that study interferes with the development of feminine faculties—and she is certainly—” He glanced at me and trailed off. “I’m sure you’ll get along splendidly. Yes, just the thing.”

“That sounds promising,” said Spector. A touch of exasperation crept into his voice. “Now, perhaps we might begin our explorations of the library?”

“Let’s get you settled in, first,” said Skinner, and this time I caught a glimpse of the predator behind the civilized words.

Spector caught it too, and raised an eyebrow. “Briefly,” he conceded. “We’re eager to get to work.”

After wandering the slushy maze of the grounds, I suspected that Skinner had sent us to Trumbull, in part, due to her inaccessibility. Eventually, however, we rounded a corner and came to the Mathematics Building. It was one of the smaller buildings on campus, but rather than being dwarfed by its neighbors it suggested a sanctum for the elite. Columns rose to either side of carven mahogany doors. All were covered in complex, abstract designs—not symmetrical, but constrained by some formula or ratio that made them by turns either pleasing or disturbing to the eye. Gargoyles on the cornice pieces draped stone tentacles around the rainspouts. I saw no recognizable gods. Still, they reminded me of the statues in Innsmouth’s central temple, or the cemetery that memorialized those lost in the cradle or at war.

The short lifespans engraved on the churchyard stones—and the paucity of those stones—loomed often in the rumors against us. I shivered as we walked between the doorposts.

Trumbull’s office door stood ajar, and through it drifted a woman’s voice, low, even, and calm, and a man’s tenor rising and falling in distress. I caught mention of ten-dimensional equations and void matrices—the jargon by which Miskatonic’s academics girded themselves against entropy. A moment later, the young man in question stormed out. His hair was shaved close, and he walked with a military stamp made ir. regular by a missing arm.

“Gi. Bill,” commented Spector approvingly. I gazed after the soldier, wondering which front he’d fought on and what he would have thought of Neko, had he noticed her. Then I wondered what he’d seen, to make the university’s coldest mathematical studies seem appealing.

Trumbull did not look up as we entered, already engrossed in a clothbound textbook. She was thin and without curves in either body or face, and she wore her hair clipped back severely. Her dark gray dress was well-tailored but extremely plain. She appeared no older than me—she might even be younger, if she’d moved quickly through her schooling.

Skinner ahemmed. “Miss Trumbull.”

She looked up, and her eyes were not young. Miskatonic’s studies are said to leave scars—but I was unaccountably reminded of my paternal grand mother, who had gone into the water before I was born. Here, though, was neither recognition nor fondness.

Skinner did not quite flinch under her gaze, but he did correct his address: “Professor Trumbull. We have a party of visiting scholars from the government. The gentlemen can stay in the visitors’ quarters in the dorms, of course, but we need some place to put the girls. You should be able to fit a couple more into your household easily enough.” He smirked.

Trumbull swept him with cold eyes, then deliberately turned back to a passage in her book. “Dr. Skinner, if you wish to hire a hostess, then by all means hire a hostess. It is not one of my native talents, nor is it one I care to develop.”

“Miss—Professor Trumbull. Hosting visitors is one of the burdens we must all take on from time to time. We can hardly send Miss Marsh and Miss Koto to the Hall School if they are to concentrate on their work at the library.”

She marked her place in the book, and this time I was the one who winced under her focused attention. With effort, I avoided checking the tidiness of my skirts. After a moment her gaze turned to Caleb, then flicked back to me.

“Innsmouth?”

I sighed inwardly—I could expect to repeat this conversation many times during our stay, but had hoped to avoid it with the younger professors. “Yes.”

“Was it not… 1928, yes? I have not misremembered.”

“Yes,” I said stiffly. “The town was destroyed in 1928. I’m here to find artifacts that might have survived.”

“Ah.” She seemed struck by this. “Yes. You and your colleague may stay in my house. As Dean Skinner has implied, however, you should not expect much from it. The college sends someone to clean once a week; I do not employ servants, nor guarantee regular meals.”

“That’s fine,” said Skinner, tension leaving his shoulders. “They can eat at the faculty spa. That’s settled, then; I’ll leave you to it.”

Trumbull raised her eyebrows after his passage. “He’s not pleased by your presence. I hope he doesn’t expect me to show you gentlemen around the dorms.”

Spector shrugged. “Now that we’re here, I imagine we can find

our way.”

“We’d really rather get started in the library,” added Caleb.

She snorted. “You wouldn’t be the only scholars sleeping there.” She set aside her book. “I don’t suppose any of you are experts in the most recent theories of algebraic topology? Or have access to obscure texts on the subject?”

We all shook our heads. Charlie said, “I have a nice edition of the Book of Eibon with R’lyehn and Latin opposing pages. But I imagine Miskatonic has one as well.”

“Nine. They assign it in graduate level anthropology classes. In any case, you might as well come and see what else they have. I would certainly be intrigued to learn what survives of fabled Innsmouth. One never does know what one will find in the collections.”

“I see their temples are still standing,” murmured Caleb.

The Crowther Library was a temple indeed—and not Innsmouth’s, where flickering lamplight glinted off statues and icons, making them seem at once intimate and unknowable. This was more like the Christian cathedrals I’d heard of, where the priests face away from the congregation, murmuring in tongues unknown to their listeners.

On entering, we found ourselves in the grand foyer. Light filtered through stained glass windows depicting obscure allegorical figures. A young man fainted against a pile of books, with abstract shapes floating above him. A woman knelt by a pool of water, dangling a pendant from a chain above the moon’s reflection. Beneath the windows ran, in Latin: The world offers its secrets to the willing mind.

No bookshelves marred the expanse of stone and marble. Around the walls, arched doorways opened into shadow, promising the world’s secrets to whoever could negotiate the mazes and barriers placed in their way.

Trumbull frowned at the windows, and led us through the far archway and into the central reading room. This chamber was somewhat more welcoming in furnishing if not scale, and both the central desk and the tables with their padded chairs were peopled by students and staff. Relatively few, since classes hadn’t yet started for the spring semester, but enough to mitigate the forbidding impression of the entrance. Caleb drifted closer, and I put my hand on his arm.

“Should we… ?” I started to ask. But Trumbull was already striding toward the desk, and the rest of us perforce followed. Once again I was aware of our motley appearance, as students peered above their texts and ashtrays to track the strangers passing through their midst.

I tried to imagine the books we sought, somewhere in this very building, that might lie beneath our hands if only we could ask the right questions. They seemed as vast and wondrous as the Yith’s own archives—and I feared that they might be near as inaccessible.

The reference librarian, a middle- aged man with thinning hair, took a deep breath and squared his shoulders. Trumbull started in before he could speak: “We’re looking for a collection of rare books, esoterica, accessioned about 1928 or ’29. Probably including duplicates of some of the common texts as well as more obscure volumes.”

And annotated throughout in the hands of my family, my neighbors, our ancestors. Some might still contain childhood essays or exercises secreted between pages. But Trumbull did not seem inclined toward such personal details, and the librarian’s face was already clouded with irritation.

“You’ll need the rare books section, and special permission from the collection man ager. Second door on the right as you come in the foyer, go through the 100 and 200 stacks until you get to the Second Supplementary Annex.”

As soon as we were back in the foyer, Caleb swore. “Special permission? Those are our books!”

Neko put a hand on his shoulder. “Keep your voice down, they’ll hear.”

“The void I will. They stole them, and now they want to keep them from us.”

“Perhaps we will try showing our credentials to the collection manager, and being polite.” Spector looked at me wryly. “I hear that works sometimes.”

“Your presence here is an abomination,” Caleb told him.

I winced, but Spector merely ducked his head. “I hope it’s a helpful one. I’m not sure anyone is in a position to apologize for the Innsmouth raid, but I can at least make some small reparation.”

“Because we’re useful to you. Would you still make ‘reparations’ if we refused to track down your Russian?”

“Caleb, please,” I said, but he shook me off and strode forward into the stacks. Charlie looked uncomfortable. Trumbull pursed her lips as if studying a mildly interesting equation. I caught up with my brother. “Like the government or hate them, a Russian who could switch bodies could do terrible things. Drop all the atomic bombs anyone’s built on all the cities they can reach. Start another war. That wouldn’t be good for anyone.”

He shrugged. “As far as I’m concerned, the land can burn. We’ve made as much use of it as we can. Let the ck’chk’ck have their turn.”

I drew back. “Let’s go find out what they’ve done with our books.”

It wasn’t as if I’d never thought such things, in dry moments. But perhaps Caleb had more than one reason to live apart from the Kotos.

The Special Collections librarian was not sympathetic.

“Certainly we have the Innsmouth collection,” he said. “Students must show scholarly necessity. Non-students—there have been incidents. Those are dangerous books.”

Already I retreated into a stiff-held spine and a face that would show only the most necessary anger. “I started reading them when I was six years old.”

“Indeed?” He shuffled back a half-step.

Caleb leaned across the desk. “ Those books belong to us—to our family. Whether or not you can handle them—” I touched his wrist and he subsided. The librarian looked on, implacable, from his chosen safe distance.

Spector stepped forward and flashed his badge. “Sir, if you won’t listen to these fine folk, then perhaps it will change your mind to know that we need the books for national security purposes.”

“Sir, this is a privately held library. If you want to see collections that we judge dangerous, you’ll need specific scholarly justification for specific volumes, like everyone else—or a warrant.”

I closed my eyes, attempting to gain some measure of calm, opened them again. “What, precisely, constitutes scholarly justification?”

“A note from the instructor of a class you are taking, or your thesis advisor.” His lips compressed. “As I said, we’ve had incidents with non-students. And with students, when our rules were more lax.”

Trumbull glided forward from her post by the door. “I am an associate professor in the Mathematics Department. I wish to explore the collection.”

He braced himself—without awareness or intention, I suspected. “Are they—are some of the volumes—relevant to a class you’re teaching?”

“I am planning my syllabus. I wish to see all of them. These people will assist me.” She put her elbows down on the desk, bringing herself closer to him. I would not have expected her to be the sort to take advantage of manly weaknesses, especially given her insistence on dignity in front of the dean. Or to be willing to play such a card for our sakes—and now it occurred to me that she, too, might have some use in mind for us. Anger rose within me, overpowering as hunger, so that for a moment I could not focus on what was happening.

The librarian blinked rapidly, and licked his lips. “I can’t—that is—” Trumbull straightened, and he recovered somewhat. “We have a policy. I must have the names of specific volumes.” He held out a sheet of paper, and pushed pen and ink across the desk. Trumbull stepped aside and flicked a finger at me. Dumbly, I took her place, and began writing such titles as I could recall. Caleb, and occasionally Charlie, murmured additional suggestions.

My hand shook, spattering ink. I trembled with the knowledge that I must inevitably forget titles, leave out obscure pamphlets that had failed to attract my childish interest in the houses of distant cousins.

“All the copies of each that you have, if you please,” I said, amazed that I could get the words out.

The librarian blanched. “If you insist on multiple copies, this is a substantial portion of the collection!”

I flinched, but Trumbull looked at him calmly and he turned away. “Perhaps if I brought out five at a time? They will be easier to track.”

“That will do,” she said, sounding indifferent once more.

We waited while he gathered assistants and retreated into the library’s further caverns. Once he was gone, I sank into a chair and buried my face in my hands. I did not cry, only tried to find my way through the maze of fear and longing that the conversation had raised around clear thought. Behind me I heard Caleb pacing, heard the swish of skirts and muffled click of patent soles as Trumbull and Spector stepped out of his way each in their turn. Air displaced on either side of me, whiffs of dusty paper and peony, and twin chairs scraped against the wooden floor. I let the world back in, cautiously, as Charlie grunted into a seat on one side of me and Neko took the other. Neither spoke, but in their presence the maze faded. I sat in an ordinary mortal building, recently built and soon to crumble, and I could face whatever awaited me here.

Caleb still paced, and I saw that his hands were shaking. At last, he pulled a pack of cigarettes from his pocket, lit one with a match.

“Caleb!” In Innsmouth, men had enjoyed their tobacco as they did elsewhere—though at some point during our incarceration, the outside world had judged it proper to smoke in mixed company. But the desert had left its mark on our lungs, and I could hardly imagine that Caleb found the stuff any more comfortable than I did.

He took the cigarette from his mouth, let it dangle. “What of it? Why should they take this from me, too?”

So it was another defiance, and one I could not entirely begrudge him. “Not near the books, though. We’ve nowhere to get replacements if you let loose a stray spark.”