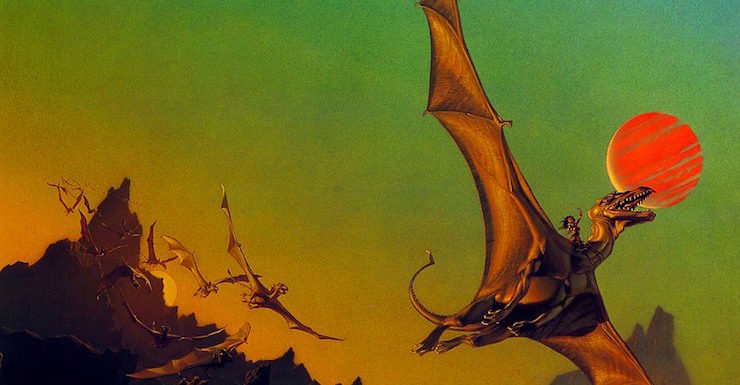

The first sex scene I ever read was between dragons. Too young and naïve to understand exactly what was happening but too smart not to get the gist of it anyway, I sank breathless-body-and-broke-open-soul into bronze Mnementh’s aerial capture of the gold queen Ramoth, and—simultaneously, of course—into Lessa’s acceptance of F’lar.

Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonflight introduced me to adulthood. I read the planetary battle against Thread and the power politics of Pern with the fascinated eagerness of a teen who understood little of Vietnam or Watergate but thirsted for justice in the world. I devoured the intricacies of intrigue in a society under an alien threat in which people nevertheless fought each other for power. I reveled in the noble heroics and in tragedy that turned triumphant.

And Lessa and F’lar’s love affair enthralled me.

The next sex scene I read was between moles. Yes, of course: moles. In Walter Horwood’s Duncton Wood novels religion and politics and violence were bound into emotion, instinct, and primal need so vibrant it left me both horrified and aching for more.

At about the same time I discovered the magic of Camber of Culdi. Dark, rich, mysterious, sacred, powerful and deeply noble, Katherine Kurtz’s Deryni filled a young heart hungry for the magic of the transcendent with passion. Then I read Tolkien. Correction: I consumed Tolkien. And when my history buff sister told me about the parallels between the Lord of the Rings and World War history… Mind. Blown. More than even my Catholic upbringing, Kurtz and Tolkien propelled me—years later—toward a PhD in Medieval Religious History.

What did these series have in common? They were big, with lush, colorful, complex worlds into which I fell gratefully, joyfully. Good and evil, epic battles, worlds hanging in the balance, powerful warriors, dark mysteries, noble sacrifices and earth-shattering finales: epic fantasy was the stuff of my youthful reading, and I imprinted on it.

But the seeds dropped by Pern, Duncton, Gwynedd and Middle-earth did not fall upon a barren field. For already I had, as a child, adored the Black Stallion novels. A hero of unmatched beauty, strength, and power, the Black nevertheless gave his heart wholly to another: a boy he loved so well that only in young Alec’s hands did the proud stallion allow himself to be tamed.

At this moment Jane Austen got inserted into my mental library (may the gods bless every fine English teacher). Austen’s comedies of petty narcissisms and love-making-under-restraint delighted me. Toss in Brontë’s Heathcliff and Catherine, and an even tighter web of social mandate and emotional scandal, and English romance caught a firm hold on my literary psyche.

So what happened when in my impressionable young womanhood Lessa intruded upon the Black? What alchemy occurred when in the eager cauldron of my imagination Camber mixed the sacred and historical with Pemberly and Captain Wentworth?

The answer to that must wait a few years because then—oh, dear reader, then!—along came Francis Crawford of Lymond. As a child of the ’70s and the daughter of a man whose pastime was reading American history, I had already devoured John Jakes’s epic American historical fiction. But Culdi and Catholicism had embedded in me an appreciation for an even earlier and foreign past, a historical tapestry woven by priests and ruled by royalty. So the moment my sister handed me Dorothy Dunnett’s The Game of Kings, my fate was set.

Already on my way to becoming a scholar of medieval history, while reading the Lymond series I saw another possibility unfurl. In my imagination appeared heroes who, like the Black, were good and noble and powerful and who, for love, would do anything. I saw heroines like Lessa who used their wit and courage and strength to conquer their own demons as well as villains determined to destroy their communities. I saw dark intrigue, lands traversed, oceans crossed and diabolical plots foiled, and an epic sort of storytelling that I felt in my deepest core like one feels the most magnificent art or music or religious ritual.

Then, like a fire upon a slow moving glacier, came Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and M.M. Kaye’s The Far Pavilions. Suddenly the tidy English nineteenth-century I had envisioned melted away to be replaced by a vastly deeper, darker, broader and fraught imperium that better resembled the fantasy fiction I had adored in my youth.

That was when I became a novelist of historical romance. Not fantasy. Not historical fiction. But romance.

Growing up I adored love stories. But I didn’t know they came in categories. In my small town bookstore, Kurtz, Dunnett, McCaffrey, Horwood and the Brontës sat side by side on the “Fiction” shelves. Back then I didn’t know a genre from a genie, and it was decades still before I learned about print runs, “also boughts,” and lateral sells. What I knew was a good story. I knew what a noble hero struggling against the forces of evil looked like. I knew what was inside the heart of a truly kickass heroine. I was an addict for complex foreign worlds and soul-spearing emotions. I learned how to be swept up and swept away. And every fantasy or historical fiction series I adored as a young reader revolved around a powerful love story. So when I taught myself how to write romance, I did so with the sensibilities of a reader of epic fantasy and historical fiction.

Genre romance began in the 1970s with the historical romantic epics of Kathleen Woodiwiss, Bertrice Small, and a handful of other authors. Their novels, while each focusing on a single romantic relationship, included scads of adventure and were set in multiple foreign locations. In the 1990s, however, a bright, smart revival of historical romance adopted a different style: stories became more Austen-like in scope, focusing almost exclusively on the interpersonal dynamic between the romantic pair, very sexy, and largely English and Scottish set.

I discovered historical romance through these newer novels, and I ate them up like gourmet candy. Julia Quinn’s “Regency” romances were my Godiva. Mary Jo Putney’s were my Cote d’Or. During graduate school I read so many Regencies as relaxations from the rigors of transcribing fourteenth-century Latin that eventually a plot for one occurred to me.

What I ended up writing didn’t look like those novels. At all. So I joined romance writers’ groups, learned the conventions of the genre, and brought my novels more in line with the books on the Romance shelves in bookstores. Not entirely, though. My mental and emotional story landscape had been shaped elsewhere. That landscape was home, where my heart felt happiest, where I felt like me.

Twenty books ago, when I set out to publish my first historical romance, I didn’t know that plunking my epically emotional, empire-crossing romances down in Austenlandia and trying to sell it to romance publishers wasn’t a super clever move. I knew big casts of characters, complex plots, and the deeds of noble heroes that had world-altering impacts. I knew what I loved in a story. So that’s what I tried to write.

What happens when authors read—and write—outside the genre boxes? Will they never sell a book, never gain a readership, never make a dime on their writing? Fantasy romance stars like Ilona Andrews, C.L. Wilson and Amanda Bouchet certainly prove it can be done successfully. Authors who mingle the conventions of different genres definitely have to search hard for willing publishers and devoted readerships. They contend with displeased readers. They grapple with covers, copyeditors, and contest rules that leave them in perilously liminal places. But all writers face these challenges. Border crossing can be challenging, but no more challenging than anything else about publishing. And it broadens genres, which is to everybody’s benefit. Also, it’s incredibly fun.

I haven’t reread most of the fantasy series or epic historical fiction that made me a reader. They nevertheless remain my first loves and the underpinnings of every novel I write.

Katharine Ashe is the USA Today bestselling author of historical romances that reviewers call “intensely lush” and “sensationally intelligent,” including an Amazon Editors’ Choice for the Ten Best Books of the Year. Her latest, The Duke, is now available. For more of her short pieces on history, feminism and genre writing, visit her at her website.

Katharine Ashe is the USA Today bestselling author of historical romances that reviewers call “intensely lush” and “sensationally intelligent,” including an Amazon Editors’ Choice for the Ten Best Books of the Year. Her latest, The Duke, is now available. For more of her short pieces on history, feminism and genre writing, visit her at her website.