I’m seventeen years old and all the oxygen in my body has abandoned me, fleeing through every accessible membrane like rats mindlessly abandoning a Spanish galleon on fire. Someone has melted a dollar’s worth of dirty pennies over my tongue and I know when I spit the viscous copper taste from my mouth I’ll see my blood make a modern art masterpiece of the canvas-covered mat below. I’m praying I didn’t just shit myself, or if I did let it be a brief, momentary loss of bowel control, and for the first time I contemplate the correlation between rubber underwear worn by state-executed inmates and spandex-clad professional wrestlers.

Hazily I watch him waddle away, the four-hundred-pound Puerto Rican wrestler (who bills himself from Samoa) who just hurled every ounce of his frame through the air and squashed me between his bulk and the corner of the wrestling ring. I forgot to put space between my back and the turnbuckles at the last moment before impact. As a result, what should’ve felt like a rougher version of a metronome bobbing on its axis in fact felt much more like being in the middle of a brick wall threesome.

Somewhere outside the ring I hear a drill instructor’s timbre filling the rafters of the converted warehouse in Jamaica, Queens. It’s Laython, nearly seven feet of the Doghouse’s head instructor. There’s no heat in the bare bones school where I’m training to become a professional wrestler, and November in New York City bites and gnashes with every subtle shift in the air.

At seventeen I love the cold. When you’re young the cold makes everything hurt less. Ten years and a thousand bone breaks later I’ll come to know even the slightest cold as some ethereal incarnation of Hanns Scharff, stone-facedly torturing my every joint and old injury for information they don’t have.

“Tell the story!” Laython’s unforgiving, merciless voice outside the ring commands. “Remember to tell the story!”

Tell the story.

* * *

I’m ten years old. The carpet is prickly under my right thigh where I spilled soda and declined to inform anyone until it petrified. I’m sitting, cross-legged and utterly rapt, in front of what I know now must’ve been the last floor model television operating in a residential home.

I’m watching the greatest story I’ve ever experienced unfold on its screen.

My uncles, my cousins, they’re all gathered around the living room to attend the live pay-per-view broadcast of the World Wrestling Federation’s biggest event of the year, Wrestlemania VIII, originating from the Hoosier Dome in Indianapolis, Indiana. Over sixty thousand people in attendance, a mass of humanity so overwhelming I can only process the images as being of a single organism sighing and swaying for half-a-mile in every direction.

The match: “Rowdy” Roddy Piper versus Bret “Hitman” Hart for the WWF Intercontinental Champion. Piper is the defending champion, the first and only title he’s ever held in the WWF despite a decade-long career with the company. Hart is the former champion who was wrongly cheated out of the title, whom he lost to another man months earlier. Both men are babyfaces, heroes, fan favorites. Read: Good guys. In 1992 such a match in the WWF is virtually unheard of. It is the era of good guys vs. bad guys—simple, proven, palpable narratives for a product more and more targeting children and young adults.

The dynamic on the screen in front of my ten-year-old self is anything but. At one time Piper was the biggest heel (read: bad guy) in the company. Working against ultimate good guy Hulk Hogan at the absolute height of the crossover media sensation known as Hulkamania, they filled arenas and stadiums around the world and drew satellite-jamming ratings. No one was dastardlier or more famous for it than Hot Rod. In the intervening years, and after a horrendous and legitimate sidelining injury, he’d used all that 1980’s infamy and post-80’s fan sympathy to cultivate himself into a beloved figure in the WWF. He’s a master of in-ring psychology and one of the best promo men in the business, and his Piper’s Pit interview segments helped build the company during the 80’s wrestling boom.

Bret Hart, meanwhile, is steadily emerging as one of the biggest stars of the new generation of WWF talent. He’s younger, cooler, more explosive and innovative as a wrestler. He’s a brand for the 90’s with his reflective wraparound sunglasses, singular pink and black attire, and Apollo Creed-esque litany of nicknames (“The Excellence of Execution,” “The Best There Is, the Best There Was, and the Best There Ever Will Be,” etc.). He’s the prodigal son of a famous and much loved Canadian wrestling dynasty. He’s fan friendly (he always gives away those signature sunglasses to a kid at ringside before every match), and his popularity is reaching critical mass.

Who do I root for? Who do I want to win, and why? Who deserves it more? Who needs it more? How can this possibly end well when one of them has to lose?

Ten-year-old me was nothing but a pot of heated questions ready to boil over at any moment.

The match starts out gentlemanly enough. They lock-up, collar and elbow, like two wrestlers having a wrestling match. There’s only one problem: Hart is a vastly superior technical wrestler. Piper is a brawler. It isn’t moments before Hart is riding Piper like a demon monkey in jockey’s garb. He clamps both hands around Piper’s wrist and Piper can’t shake him or break the hold. He charges around the ring like a wild man until he’s pulled down to the mat by a 245-pound pink and black anchor. Hart locks both arms around his waist and no amount of bucking or yelling or thrashing can dismount him. Piper is being out-wrestled on every front.

Then we see the first shades of the Piper of old: He spits at Bret Hart.

The crowd, that endless sea of humanity, roars their disapproval and Piper feels it crash over him like a wave sent by Poseidon. You see the regret on his face, the hesitance. It’s the first volley of a beautiful psychological ping-pong. It begins with the more benign question, “Can Piper keep his famous temper in-check?” and escalates to the malign and more dangerous question, “How far will Piper go to keep the only gold he’s ever worn around his waist?” Finally, the deadly existential question, “Will Piper turn heel?”

Piper becomes a violent Willy Wonka, a black hole of motivations, false personas, and hidden agendas and menace. In one moment, after forcing them both spectacularly out of the ring, he’s holding the ropes open for Hart in a show of respect and repentance. In the next moment he’s throwing a cheap shot uppercut as Hart bends to retie his bootlaces.

It’s that cheap shot which busts Hart wide open, and within moments his face is covered in blood. This was a sight unseen in the family-friendly WWF, who’d banned blood during their matches at the time, but it heightened the tension and danger and distress and suspense in a way my ten-year-old mind could barely contain.

The climax they create is a single, perfect moment of moral drama. The referee has been inadvertently felled (this is known classically as “bumping the ref”). For the moment, anything goes in the match as long as the ref isn’t conscious to see it. Bret Hart is down, bloodied, and Piper is a man possessed. He storms out of the ring, violently shoves aside the timekeeper, and snatches the steel ring bell to use as a weapon.

That moment, Bret Hart prostrate and helpless and covered in his own blood on the mat, Piper towering over him holding that steel ring bell with all the malice of an angry demigod, hesitant but determined, is everything. No one in attendance is queued at the concession stands. The bathrooms are empty. The lives of sixty thousand people in that moment hinge entirely on the next decision Piper makes. They’re there, we all are, tuned in and this is as real as anything that’s ever happened in our own lives.

I could almost see the miniature avatars of Piper astride his own shoulders, one horned and fork-tongued and fire-skinned and the other haloed and harp-strumming. The Devil of his nature is hissing, “Do it! Drill him with the bell! Damn these people and their judgments! It’s all about the gold!” while his better angel pleads, “We’ve come so far. We’ve traveled such a long road to redemption. We won this belt fairly. If we don’t keep it the same way, what’s the point?”

And Piper plays that moment and us like a master conductor. He soaks up every cheer and jeer and reprimand from the crowd, registering it as anguish and conflict on a face that seems to play to all of us individually, like a silent conversation between my ten-year-old self and Roddy Piper, warring with his very nature for the fate of his soul. I didn’t know what he was going to do, right up until the very second he dropped that bell and chose to wrestle the match straight.

That decision cost him the match and the title, but both he and Bret Hart left that ring and that stadium as heroes.

Twenty-four years have passed since that day, and I’ve never been more invested in or rewarded by a story told to me in any medium, any format, be it novel, television, film, comics, or song.

It was a masterpiece.

* * *

There are a million stories to tell in a pro-wrestling ring, all of them without speaking a single word. Fans today may not be able to appreciate that; you’ve grown up in an era of fifteen-minute promos and workers spending more time with microphones in their hands than their boots on the canvas. And if you’re not nor have you ever been a fan, you obviously don’t know what the hell I’m talking about. Odds are fair you see and have always seen pro-wrestling as a low-class, frustratingly and obviously fake celebration of violence, nothing more.

You’re wrong.

I’m a professional writer now. But I was a professional wrestler for ten years of my life. I began training when I was scarcely fifteen and retired in my mid-twenties. I wrestled all over the United States and Mexico, more matches than I can count, sometimes three shows in a single weekend. I know what pro-wrestling is, what it isn’t, what it was, and what it will never be again.

I want to tell you a couple of things that are true.

Wrestling was my first professional job as a storyteller.

More than that, pro-wrestling is what taught me how to be a good storyteller.

The truth is pro-wrestling is not unlike fiction writing; it’s a medium composed of many forms. Like prose, you can use the medium to tell an epic saga, a story that plays out over months or even years and culminates with an epic “blow-off” main event pay-per-view match which resolves all arcs and storylines of that story (we call them “angles,” but they’re stories, pure and simple), or you can use it to create micro-fiction, a single, short, simple story created in one match between two wrestlers you’ve never heard of or seen before and for which no other context is required to understand the narrative.

Learning those forms, and learning how to execute them on command, is (or was) the essence of true and truly good professional wrestling. Piper vs. Hart was and is, for me, the definitive text on the subject because it is universal storytelling. No extra context is required to understand the narrative of that match. If you’ve never watched wrestling, never heard of these two guys in spandex, you can watch that match from the beginning bell and fully understand the story of what they’re doing. More than that, you’ll still be deeply compelled by it. It speaks to everyone, and no frills or explanation or complex worldbuilding or monologue or exposition is necessary. I can’t think of a more cross-applicable storytelling lesson than that.

That concept of universal storytelling is simple to grasp and agonizingly difficult to execute in any medium, and it’s what drives my prose fiction to this day.

Pro-wrestling did teach me how to use words. The pro-wrestling promo (whether it’s a backstage interview, or an “in-ring” in which you stand alone with a microphone in the ring addressing the crowd) is an art form unto itself. The wrestlers who truly mastered it could make you feel and believe whatever they wanted you to feel and believe. Ric Flair could thrill you and sell you. Dusty Rhodes could rally you. Jake Roberts could spellbind and terrify you even as you rooted for him to succeed.

But the promo, again in its purest form, was always prologue. The promo sold the angle, it didn’t replace or become the angle.

The story always unfolded in the ring.

Words, in my opinion, are what ruined professional wrestling in America. They corrupted the art form (just as trying to replace prose with live-action in a novel would transform the novel into something else entirely). Pro-wrestling was once “booked,” meaning a single individual (the “booker”) or a group (the “booking committee”) conceived the angles, their direction, and their outcome. Contrary to popular belief, there was no script in pro-wrestling. Improvisation and organic growth were key.

Words, in my opinion, are what ruined professional wrestling in America. They corrupted the art form (just as trying to replace prose with live-action in a novel would transform the novel into something else entirely). Pro-wrestling was once “booked,” meaning a single individual (the “booker”) or a group (the “booking committee”) conceived the angles, their direction, and their outcome. Contrary to popular belief, there was no script in pro-wrestling. Improvisation and organic growth were key.

That’s all changed. Television writers who script wrestling as if it were a dramatic series like any other has largely replaced booking. And as “reality” television has taught us, when you heavily script these shows, you end up with a reality no one believes, which pretty much leaves you with a shitty version of a scripted drama.

Now, many of you will watch the professional wrestling of any era and never see anything more than a bunch of sweaty dudes pretend fighting. That’s fine. I don’t take umbrage and I’m not here to change your mind. But the fact remains you don’t know what it is. I know what it is because I watched it for a third of my life and spent another third living it. Your cursory opinion, almost universally formed second or third or even forth-hand, means nothing to me, as do all uninformed opinions.

No, I’m not here to sell you or alter your uninformed opinion of pro-wrestling or even just to extol the virtues of my former craft and profession. It’s not even about pro-wrestling specifically. I’m here because I imagine most, if not all of you are storytellers, either practicing or aspiring (because everybody wants to be a writer or thinks they already are, right?). And that’s grand. That’s a fine thing to be. I still believe in prose as a storytelling form. I still seek and even sometimes find a singular grace in the medium. I reject the notion of obsolescence either impending or having already arrived.

Being a good writer demands an ability to use words and command a written language. Being a good storyteller has nothing to do with words. They are separate skills that you merge together to (hopefully) elevate both. Learning to craft with words was a separate journey for me, but I wouldn’t be any kind of storyteller if I hadn’t inadvertently looked beyond words in that early part of my life and career. It took me places words couldn’t, and everything I brought back I can and do apply to my writing. Those places taught me what to write about, and how to show rather than tell.

I advise you to do the same. Look beyond words, in whatever form strikes your fancy. There are multitudes out there. The novel is still a relatively new invention, believe it or not. It’s worth knowing how stories were told and why they moved people and lived on far past the longevity of the storyteller before the written word came along.

You might reject this entire hypothesis entirely. That’s fair. The fact remains, I have over a decade of experience telling stories without using a single word, written or spoken. It helped me to first understand storytelling on the most visceral human level. I understand what moves people, what drives their adoration and ire and every base and even more complex emotion in-between. I know how to evoke those emotions silently and solely with the language of movement.

After ten years of that, if you let me actually use words to tell a story I’m unstoppable.

The article was originally published in November 2016 as past of our Related Subjects series.

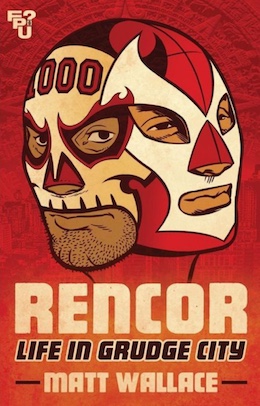

Matt Wallace is the author of The Next Fix, The Failed Cities, and the novella series Slingers. He’s also penned over one hundred short stories, some of which have won awards and been nominated for others, in addition to writing for film and television. Greedy Pigs, book 5 in the Sin du Jour novella series, is available now from Tor.com Publishing, with book 6, Gluttony Bay, forthcoming in November. Matt now resides in Los Angeles with the love of his life and inspiration for Sin du Jour’s resident pastry chef.

Matt Wallace is the author of The Next Fix, The Failed Cities, and the novella series Slingers. He’s also penned over one hundred short stories, some of which have won awards and been nominated for others, in addition to writing for film and television. Greedy Pigs, book 5 in the Sin du Jour novella series, is available now from Tor.com Publishing, with book 6, Gluttony Bay, forthcoming in November. Matt now resides in Los Angeles with the love of his life and inspiration for Sin du Jour’s resident pastry chef.