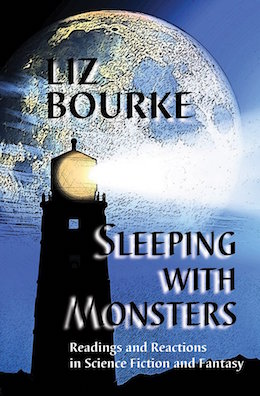

We’re pleased to share Kate Elliott’s introduction to Liz Bourke’s essay collection, Sleeping With Monsters—some of which are taken from her column here at Tor.com. Bourke’s subjects range from the nature of epic fantasy—is it a naturally conservative sort of literature?— to Mass Effect’s decision to allow players to play as a female hero, and from discussions of little-known writers to some of the most popular works in the field.

Bourke herself writes that the collection’s purpose is ”to be a little loud and angry. To celebrate the work of women in the science fiction and fantasy (SFF) field. To offer a snapshot, a limited glimpse, of what I think is best, most fun, most interesting.” A provocative, immensely readable collection of essays about the science fiction and fantasy field, from the perspective of a feminist and a historian, Sleeping With Monsters is an entertaining addition to any reader’s shelves, available July 1st from Aqueduct Press.

Sleeping With Monsters

Introduction

Back in the Neolithic before the rise of the World Wide Web and the later explosion of social media, science fiction and fantasy review venues were few and far between. Seen from the perspective of an outsider, they were curated as objective stations where a few well-chosen and perspicacious reviewers might wisely or perhaps in a more curmudgeonly fashion guide the tastes and reading habits of the many. There is a kind of review style that parades itself as objective, seen through the understood-to-be-clear lens of earned authority, judging on the merits and never bogged down by subjectivity. Often (although not always) these reviews and review sites took (or implied) that stance: We are objective, whereas you are subjective. Even if not directly framed as objective, such reviews had an outsize authoritativeness simply because they stood atop a pedestal that few could climb. Controlling access to whose voice is seen as authoritative and objective is part of the way a narrow range of stories become defined as “universal” or “worthy” or “canon,” when a few opinion-makers get to define for the many.

The rise of the world wide web and the explosion of social media changed all that. As voices formerly ignored or marginalized within the Halls of Authority created and found platforms from which to speak, to be heard, and to discuss, the boundaries of reviewing expanded. Anyone could weigh in, and often did, to the consternation of those who wished to keep the reins of reviewing in their more capable and superior hands. Influenced in part by the phrase “the personal is political,” many of these new reviewers did not frame their views as rising atop a lofty objective spire but rather wallowed in the lively mud of their subjectivity, examining how their own perspective shaped their view of any given narrative whether book, film and tv, or game.

It was in this context (in the webzine Strange Horizons, to be exact) that I discovered the reviews of Liz Bourke. Gosh, was she mouthy and opinionated!

I am sure Liz is never as blunt as she might be tempted to be; at times the reader can almost taste her restraint. Nevertheless, some of her reviews may make for uncomfortable reading. She jabs at issues of craft and spares no one from criticism of clumsy verbiage, awkward plotting, clichéd characterization, and lazy worldbuilding. She consistently raises questions about the sort of content in books that for a long time was invisible to many reviewers or considered not worth examining. Uncovering the complex morass of sexism, racism, classism, ableism, religious bigotry, and homo- and transphobia that often underlies many of our received assumptions about narrative is right in her wheelhouse. She says herself that this collection “represents one small slice of one single person’s engagement with issues surrounding women in the science fiction and fantasy genre,” and she uses this starting point to examine aspects embedded deep within the stories we tell, often aiming a light onto places long ignored, or framing text and visuals within a different perspective. In her twinned essays discussing how conservative, or liberal, epic and urban fantasy may respectively be, she both questions the claim that epic fantasy is always conservative while suggesting that urban fantasy may not be the hotbed of liberalism that some believe it to be: “popular fiction is seldom successful in revolutionary dialectic.”

Strikingly, she is always careful to reveal her subjectivities up front by making it clear she has specific filters and lenses through which she reads and chooses to discuss speculative fiction and media. For example, she introduced her Tor.com Sleeps With Monsters column by stating up front her intention to “keep women front and center” as subjects for review in the column. She writes (only somewhat tongue-in-cheek) that “Cranky young feminists (such as your not-so-humble correspondent) aren’t renowned for our impartial objectivity.” When she writes about the game Dishonored, noting its gender limitations, she concludes: “And if you do shove a society where gender-based discrimination is the norm in front of me in the name of entertainment, then I bloody well want more range: noblewomen scheming to control their children’s fortunes, courtesans getting in and out of the trade, struggling merchants’ widows on the edge of collapse and still getting by; more women-as-active-participants, less women-as-passive-sufferers. I would say this sort of thing annoys me, but really that’s the wrong word: it both infuriates and wearies me at the same time. I’m tired of needing to be angry.”

By refusing to claim objectivity, her reviews explode the idea that reviews can ever be written from a foundation of objectivity. People bring their assumptions, preferences, and prejudices into their reading, whether they recognize and admit it or not. The problem with reviews and criticism that claim or imply objectivity is that they leave no room for the situational but rather demand a sort of subservience to authority. They hammer down declarations. By acknowledging there are views that may not agree with hers, Liz creates a space where the readers of her reviews can situate their own position in relationship to hers, as when she enters into the debate over canon and declares that “canon is a construct, an illusion that is revealed as such upon close examination.” She goes farther, as in her essay on queer female narrative, to specifically discuss the question within the frame of “the personal narrative and me” and how “the politics of representation” and the presence of queer women in stories changed her own view of herself.

As a reviewer Bourke talks to us as if we’re in conversation. What a pleasure it is to read pithy reviews of often-overlooked work I already admire, as well as to discover books I need to read. She enthuses about writers whose work is “arrestingly unafraid of the tensions at its heart” as she writes about Mary Gentle’s The Black Opera, and devotes a series of reviews to the ground-breaking 1980s fantasy works of the incomparable Barbara Hambly. She can be angry, as when discussing the use of tragic queer narratives in fiction as “a kick in the teeth,” and express disappointment in writers who trot out the tired old argument that “historical norms may limit a writer’s ability to include diverse characters.” But there’s also room for a lighter-hearted examination of, for example, C. J. Cherryh’s Foreigner series in an essay that analyzes how the hero of the series, Bren Cameron, “rather reminds me of a Regency romance heroine—not for any romantic escapades, but for the tools with which he navigates his world.” Her argument invites us to consider our own reading habits—the Regency romance as descended through Jane Austen and Georgette Heyer has become a sub-genre read and loved by many within the sff community—and thereby to see how cross-genre reading casts its influences.

This aspect of dialogue creates immediacy and intimacy as well as disagreement and even indignation. But think about what it means in the larger sense: situationally-oriented reviews create interaction. Just as every reader interacts with the text or media they are engaged in, so can reviews expand on that interaction. And if that makes Liz Bourke a rabble-rouser who pokes a stick into people’s cherished assumptions and encourages us to examine and analyze and to talk with each other, then we are the more fortunate for it.

Excerpted from Sleeping With Monsters © 2017 by Liz Bourke