“Novels are not slogans,” Margaret Atwood said in a 1986 New York Times feature in response to assertions that The Handmaid’s Tale was a feminist tract. “If I wanted to say just one thing I would hire a billboard. If I wanted to say just one thing to one person, I would write a letter. Novels are something else. They aren’t just political messages. I’m sure we all know this, but when it’s a book like this you have to keep on saying it.”

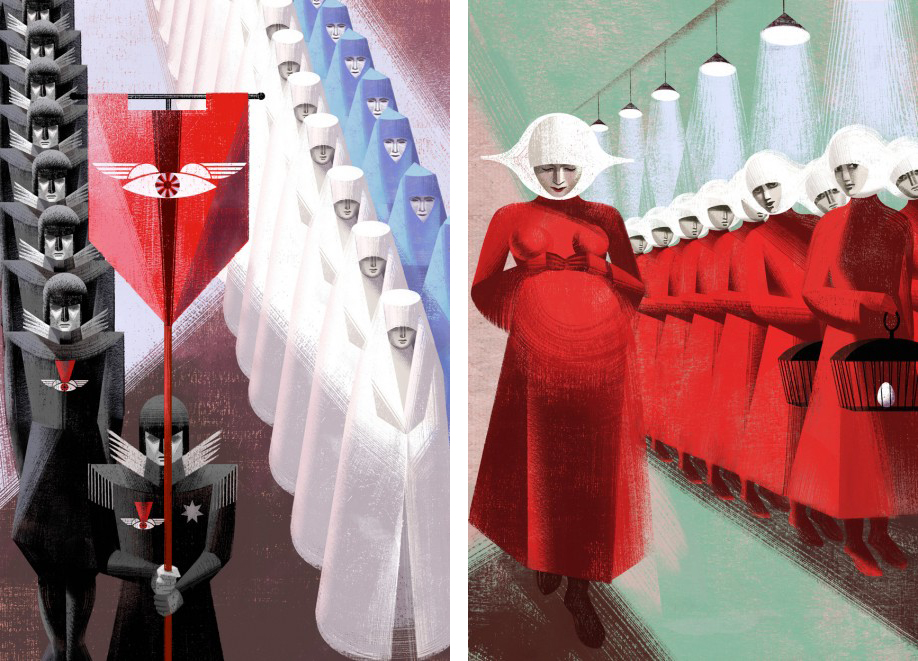

What’s fascinating about the legacy of The Handmaid’s Tale is how it’s spread to almost every medium: reimagined on stage and screen, buzzing on the airwaves and between your ears, inked earnestly onto skin and snarkily onto protest signs, embodied in real bodies through viral marketing and political action. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list; rather, it’s a look at the breadth of Atwood’s influence, and how you can see Offred’s story from tech conferences to the Senate floor.

For most books, there’ll be a movie or TV adaptation; not only does Handmaid have both, but they are far from the only interpretations. In the early 2000s, both BBC Radio 4 and CBC Radio released dramatic radio plays. The former, adapted by John Dryden, takes a documentary-style approach and was lauded for its “faultless acting and imaginative, varied, and multi-layered sound effects.” Playwright Michael O’Brien adapted the Canadian take, with a robust cast and a more streamlined narrative that focuses on the most dramatic moments of the book.

Secrets, Crimes & Audiotapes’ podcast adaptation is perhaps the biggest departure from the source material (at least in the audio sphere): It presents Offred’s story chronologically, beginning with her, Luke, and her daughter trying to cross the border; then her capture and training at the Red Center; and only then does she become Offred. We don’t even meet the rest of the household until a few episodes in (there are six installments total). While this was initially jarring, having just reread the book with its jumping back and forth between present and past, I appreciate the commitment to a more linear narrative, carrying us along with Offred so that we experience her emotions in the moment (instead of in retrospect) and change along with her.

On the stage, we have seen Offred’s story in the form of a both a traditional play adaptation (in 2002) and a one-woman show (in 2015). The latter is set entirely in Offred’s room—a bed, a lamp, a chair—from which the Handmaid relates her tale; the lead’s ability to “frequently and skillfully [quote] dialogue from other characters” communicates the scope of Gilead outside of her small prison. A 2003 opera, commissioned by the Royal Danish Opera, fell short of its ambitions, despite its inventive use of staging (including video) and “wonderfully committed” performances. A decade later, the Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s “dance-drama” take on Atwood’s dystopia was praised as “edgy” and “gripping.”

One of my personal favorite demonstrations of the book’s legacy was the Handmaid’s Tale tattoo chain collaboration among Book Riot Live, Litographs, and Random House in 2015: They took the text of the first two chapters of Atwood’s classic dystopian novel, broke it into 350 lines or phrases, then distributed the temporary tattoos to volunteers at Book Riot Live. Each person photographed their arms or necks or other body parts, with the end result being a photo series of the text as written across 350 bodies. Atwood herself kicked off the tattoo chain with the first line.

Margaret Atwood admiring the Handmaid's Tale tattoo chain! #brlive pic.twitter.com/lDPli8g108

— Book Riot (@BookRiot) November 8, 2015

A 1986 NYT feature on Atwood and the novel emphasizes the hope in there being a post-Gilead era:

“You’ll notice,” she says, “and not many people have, that the section on Newspeak at the end of Nineteen Eighty-Four talks about Newspeak in the past tense. It’s written in ordinary language, not Newspeak. The obvious implication from that is that the regime has fallen, that someone in the future, we don’t know who, has lived to tell the tale and to write this analysis of Newspeak in the past tense.

“And my book isn’t totally bleak and pessimistic either, for several reasons. The central character—the Handmaid Offred—gets out. The possibility of escape exists. A society exists in the future which is not the society of Gilead and is capable of reflecting about the society of Gilead in the same way that we reflect about the 17th century. Her little message in a bottle has gotten through to someone—which is about all we can hope, isn’t it?”

A new edition of the audiobook (narrated by Claire Danes) plays to this optimism, with Atwood contributing new material that builds on the final line of Are there any questions? Professor Pieixoto answers 10 of them: How was the footlocker of cassette tapes discovered? Was Offred ever reunited with her daughter? Have there been attempts to recover DNA samples from that time period? When asked about the Mayday resistance, Pieixoto mentions that they might have uncovered some new material, which could be Atwood’s sly way of hinting at new work:

“I and my team have made some fresh discoveries, but I am not yet at liberty to share them. We do not wish to rush to publication before we have double and triple checked our material from the standpoint of authenticity. People have been taken in by clever forgeries before. Long ago there were the spurious Hitler diaries and more recently, I have to say, the very well done Aunt Lydia’s Log Book. We wish to be sure of our ground, but give us a year or two, and I hope you will be pleasantly surprised.”

For all that The Handmaid’s Tale is enjoying a resurgence of attention decades after its publication, Atwood knows that the dystopian genre is ever-shifting. When NPR asked her what she thinks the next big dystopian novel is, she was thinking outside of pages and spines:

Well, it won’t be a book, according to Atwood. “The question to be asked is, if somebody does write such a novel where will it be published?” she says. “I think we might go back to newspaper serials … Because events are evolving so fast it would almost take a serial form to keep up with them.”

One installment a week, Atwood says, and “I would make my narrator somebody from within one of the alt-Twitter handles that are popping up all over—as alternative Department of Justice, alternative Parks Department, alternative Education.” Someone inside the government, who’s risking their job to leak information to the public.

A profile in the New Yorker crowning Atwood the “prophet of dystopia” makes mention of how at least one participant in the Women’s March held up a sign reading “MAKE MARGARET ATWOOD FICTION AGAIN.” Two months later, activists dressed as Handmaids walked into the Texas Senate to protest two anti-abortion bills.

That’s free marketing for the Hulu series, which has been utilizing its richly visual source material for viral marketing opportunities. I spotted the above graffiti painted (though made to look as if it had been scratched) in the bathrooms at last year’s New York Comic-Con. But then Hulu upped the ante at SXSW last month by hiring women to walk through Austin, TX, dressed as handmaids, with the official Twitter account inviting onlookers to ask the women if they would like to walk to the river. While that particular publicity stunt might have been a bit creepier than Hulu intended, it was certainly memorable.

.@Hulu is doing a great job creeping everyone out at #sxsw with all these handmaids walking around in complete silence. pic.twitter.com/fGxKaPJyz2

— Adweek (@Adweek) March 10, 2017

“Why do I do such a painful task?” Atwood asked during her acceptance speech for the National Book Critics Circle award ceremony in early 2017. “For the same reason I give blood. We must all do our part, because if nobody contributes to this worthy enterprise then there won’t be any, just when it’s most needed.”

Next week, we’re watching the 1990 film adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale! I’ve never seen it (though the trailer looks delightfully dramatic), and I figured it would make for a good visual comparison to the TV series, which premieres the following week.

Natalie Zutter is seriously considering a Nolite te bastardes carborondorum tattoo, among many others inspired by this job. Find her on Twitter and Tumblr.