Hubert, Etc was too old to be at that Communist party.

After watching the breakdown of modern society, Hubert Vernon Rudolph Clayton Irving Wilson Alva Anton Jeff Harley Timothy Curtis Cleveland Cecil Ollie Edmund Eli Wiley Marvin Ellis Espinoza—known to his friends as Hubert, Etc—really has no where left to be, except amongst the dregs of disaffected youth who party all night and heap scorn on the sheep they see on the morning commute. After falling in with Natalie, an ultra-rich heiress trying to escape the clutches of her repressive father, the two decide to give up fully on formal society—and walk away.

After all, now that anyone can design and print the basic necessities of life—food, clothing, shelter—from a computer, there seems to be little reason to toil within the system.

It’s still a dangerous world out there, the empty lands wrecked by climate change, dead cities hollowed out by industrial flight, shadows hiding predators animal and human alike. Still, when the initial pioneer walkaways flourish, more people join them. Then the walkaways discover the one thing the ultra-rich have never been able to buy: how to beat death. Now it’s war—a war that will turn the world upside down.

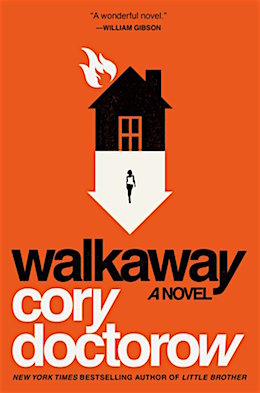

Fascinating, moving, and darkly humorous, Cory Doctorow’s Walkaway is a multi-generation SF thriller about the wrenching changes of the next hundred years, and the very human people who will live their consequences—available April 25th from Tor Books! Read a selection from the second chapter below, or head back to the beginning with chapter one.

2

You All Meet in a Tavern

[i]

Sundays at the Belt and Braces were the busiest, and there was always competition for the best jobs. The first person through the door hit the lights and checked the infographics. These were easy enough to read that anyone could make sense of them, even noobs. But Limpopo was no noob. She had more commits into the Belt and Braces’ firmware than anyone, an order of magnitude lead over the rest. It was technically in poor taste for her to count her commits, let alone keep a tally. In a gift economy, you gave without keeping score, because keeping score implied an expectation of reward. If you’re doing something for reward, it’s an investment, not a gift.

In theory, Limpopo agreed. In practice, it was so easy to keep score, the leaderboard was so satisfying that she couldn’t help herself. She wasn’t proud of this. Mostly. But this Sunday, first through the door of the Belt and Braces, alone in the big common room with its aligned rows of tables and chairs, all the infographics showing nominal, she felt proud. She patted the wall with a perverse, unacceptable proprietary air. She helped build the Belt and Braces, scavenging badlands for the parts its drone outriders had identified for its construction. It was the project she’d found her walkaway with, the thing uppermost in her mind when she’d looked around the badlands, set down her pack, emptied her pockets of anything worth stealing, put extra underwear in a bag, and walked out onto the Niagara escarpment, past the invisible line that separated civilization from no-man’s-land, out of the world as it was and into the world as it could be.

The codebase originated with the UN High Commission on Refugees, had been field-trialled a lot. You told it the kind of building you wanted, gave it a scavenging range, and it directed its drones to inventory anything nearby, scanning multi-band, doing deep database scrapes against urban planning and building-code sources to identify usable blocks for whatever you were making. This turned into a scavenger hunt inventory, and the refugees or aid workers (or, in shameful incidents, the trafficked juvenile slaves) fanned out to retrieve the pieces the building needed to conjure itself into existence.

These flowed into the job site. The building tracked and configured them, a continuously refactored critical path for its build plan that factored in the skill levels of workers or robots on-site at any moment. The effect was something like magic and something like ritual humiliation. If you installed something wrong, the system tried to find a way to work around your stupid mistake. Failing that, the system buzzed your haptics with rising intensity. If you ignored them, it tried optical and even audible. If you squelched that, it started telling the other humans that something was amiss, instructed them to fix it. There’d been a lot of A/B splitting of this—it was there in the codebase and its unit-tests for anyone to review—and the most successful strategy the buildings had found for correcting humans was to pretend they didn’t exist.

If you planted a piece of structural steel in a way that the building really couldn’t work with and ignored the rising chorus of warnings, someone else would be told that there was a piece of “misaligned” material and tasked to it, with high urgency. It was the same error that the buildings generated if something slipped. The error didn’t assume that a human being had fucked up through malice or incompetence. The initial theory had been that an error without a responsible party would be more socially graceful. People doubled down on their mistakes, especially when embarrassed in front of peers. The name-and-shame alternate versions had shown hot-cheeked fierce denial was the biggest impediment to standing up a building.

So if you fucked up, soon someone would turn up with a mecha or a forklift or a screwdriver and a job ticket to unfuck the thing you were percussively maintaining into submission. You could pretend you were doing the same job as the new guy, part of the solution instead of the problem’s cause. This let you save face, so you wouldn’t insist you were doing it right and the building’s stupid instructions (and everything else in the universe) was wrong.

Reality was chewily weirder in a way that Limpopo loved. It turned out that if you were dispatched to defubar something and found someone who was obviously the source of the enfubarage, you could completely tell the structural steel wasn’t three degrees off true because of slippage: it was three degrees off true because some dipshit flubbed it. What’s more, Señor Dipshit knew that you knew he was at fault. But the fact that the ticket read URGENT RETRUE STRUCTURAL MEMBER-3’ AT 120° NNE not URGENT RETRUE STRUCTURAL MEMBER-3’ AT 120° NNE BECAUSE SOME DIPSHIT CAN’T FOLLOW INSTRUCTIONS let both of you do this mannered kabuki in which you operated in the third person passive voice: “The beam has become off-true” not “You fucked up the beam.”

That pretense—researchers called it “networked social disattention” but everyone else called it the “How’d that get there?” effect—was a vital shift in the UNHCR’s distributed shelter initiative. Prior to that, it had all been gamified to fuckery, with leaderboards for the most correct installs and best looters. Test builds were marred by angry confrontations and fistfights. Even this was a virtue, since every build would fissure into two or three subgroups, each putting up their own buildings. Three for the price of one! Inevitably, these forked-off projects would be less ambitious than the original plan.

Early sites had a characteristic look: a wide, flat, low building, the first three stories of something that had been planned for ten before half the workers quit. A hundred meters away, three more buildings, each half the size of the first, representing forked and re-forked buildings revenge-built by alienated splitters. Some sites had Fibonacci spirals of ever-smaller forks, terminating in a hostility-radiating Wendy House.

The buildings made the leap from the UNHCR repo to the walkaways and mutated into innumerable variations beyond the clinic/school/shelter refugee pantheon. The Belt and Braces was the first tavern ever attempted. Layouts for restaurant kitchens weren’t far off from the camp kitchens, and big common spaces were easy enough, but the actual zeitgeist of the thing was substantially different, tweaked in a thousand ways so that you’d never walk into it and say, “This is a refugee residence that’s been converted to a restaurant.”

But you’d never mistake the Belt and Braces for a normal restaurant. Its major feature was the projection-mapped lighting that painted surfaces and items throughout its interior with subtle red/green tones telling you where something needed human attention. This was the UNHCR playbook, but again, there was a world of difference between dishing up M.R.E.s to climate refus and serving fancy dry-ice cocktails made from wet-printers and powdered alcohol. No refugee camp ever went through quite so many cocktail parasols and perfect-knot swizzle sticks.

On an average day, the Belt and Braces served a couple hundred people. On Sundays, it was more like five hundred. The influx of noobs brought scouts for talent, sexual partners, bandmates, playmates, and, of course, victims. Being the first one through the door meant that Limpopo would get to play maître d’.

The assays showed last night’s beer had come up well. The hydrogen cells were running 45 percent, which would run the Belt and Braces for two weeks flat out—the eggbeaters on the roof had been running hard, electrolyzing waste water and pumping cracked hydrogen into the cells. There were fifty cells in the basement, harvested out of abandoned jets the drones had spotted. The jets hadn’t been airworthy in a long time, but had yielded quantities of matériel for the Belt and Braces, including dozens of benches made from their seats. The hard-wearing upholstery came clean, its dirt-shedding surfaces revealing designs with each wipe of their rags like reappearing disappearing ink.

But the hydrogen cells had been the biggest find of all; without them, the Belt and Braces would have been very different, prone to shortages and brownouts. Limpopo fretted that they’d be stolen; it took all her self-control not to install surveillanceware all around the utility hatches.

The pre-prep stuff on the larders showed green, but she still made a point of personally sniffing the cheese cultures and prodding the dough through its kneading-film. The sauce precursors smelled tasty, and the ice-cream maker hummed as it lazily aerated the frozen cream. She called for coffium and sat skewered on a beam of light in the middle of the commons as the delicious, fruity, musky aroma wafted into the room.

The first cup of coffium danced hot in her mouth and its early-onset ingredients percolated into her bloodstream through the mucous membranes under her tongue. Her fingertips and scalp tingled and she closed her eyes to enjoy the effects the second-wave substances brought on as her gut started to work. Her hearing became preternatural, the big muscles in her quads and pecs and shoulders got a fiery feeling like dancing while standing still.

She took another deep draught and closed her eyes, and when she opened them again, she had company.

They were such obvious noobs they could have come from central casting. Worse, they were shleppers, their heavy outsized packs, many-pocketed trekking coats, and cargo pants stuffed to bulging. They looked overinflated. Shleppers were neurotic and probably destined to walkback within weeks, leaving behind lingering interpersonal upfuckednesses. Limpopo had gone walkaway the right way, with nothing more than clean underwear, which turned out to be superfluous. She tried not to prejudge these three, especially in that giddy first five minutes of her coffium buzz. She didn’t want to harsh her mellow.

“Welcome to the B and B!” she shouted, louder than intended. They flinched, then rallied.

“Hi there,” the girl said, and walked forward. Her clothes were beautiful, bias-cut and contrast stitched. Limpopo immediately coveted them. She’d pull the girl’s image from the archives later and decompose the patterns and run a set for herself. She’d be the envy of all who saw her, until the design propagated and became old news. “Sorry to just walk in, but we heard—”

“You heard right.” Limpopo’s voice was quieter but still too shouty. Either the coffium had to burn down so she could control her affect, or she needed to drink a lot more so she could stop giving a shit. She thumped the refill zone and put her cup under the nozzle. “Open to everyone, all day, every day, but Sundays are special, our way of saying hello to our new neighbors and getting to know them. I’m Limpopo. What do you want to be called?”

The phrasing was particular to the walkaways, an explicit invitation to remake yourself. It was the height of walkaway sophistication to greet people with it, and Limpopo used it deliberately on these three because she could tell they were tightly wound.

The shorter of the two guys, with a scruffy kinked beard and a stubbly shaved head stuck his hand out. “I’m Gizmo von Puddleducks. This is Zombie McDingleberry and Etcetera.” The other two rolled their eyes.

“Thank you, ‘Gizmo,’ but actually, you can call me Stable Strategies,” the girl said.

The other guy, tall but hunched over with an owlish expression and exhaustion lines on his face, sighed. “You might as well call me Etcetera. Thanks, ‘Herr von Puddleducks.’ ”

“Very pleased to meet,” Limpopo said. “Why don’t you put your stuff down and grab a seat and I’ll get you some coffium, yeah?”

The three looked at each other and Gizmo shrugged and said, “Hell yeah.” He shrugged out of his pack and let it fall to the floor with a thump that made Limpopo jump. Jesus fuck, what were these noobs hauling over hill and dale? Bricks?

The other two followed suit. The girl took off her shoes and rubbed her feet. Then they all did it. Limpopo wrinkled her nose at the smell of sweaty feet and made a note to show them the sock exchange. She squeezed off three coffiums, using the paper-thin ceramic cups printed with twining, grippy texture strips. She set the cups down onto saucers and added small carrot biscuits and pickled radishes and carried them to the noobs’ table on a tray that clicked into a squared-off dock. She got her jumbo mug and brandished it: “To the first days of a better world,” she said, another cornball walkaway thing, but Sundays were the day for cornball walkaway things.

“The first days,” Etcetera said, with surprising (dismaying) sincerity.

“First days,” the other two said and clinked. They drank and were quiet while it kicked off for them. The girl got a cat-with-canary grin and took short, loud breaths, each making her taller. The others were less demonstrative, but their eyes shone. Limpopo’s own dose was optimal now, and she suddenly wanted these noobs to be as welcome as possible. She wanted them to feel awesome and confident.

“You guys want brunch? There’s waffles with real maple syrup, eggs as you like ’em, some pork belly and chicken ribs, and I’m pretty sure croissants, too.”

“Can we help?” Etcetera said.

“Don’t sweat that. Sit there and soak it in, let the Belt and Braces take care of you. Later on, we’ll see if we can get you a job.” She didn’t say they were too noob to have earned the right to pitch in at the B&B, that walkaways for fifty clicks would love to humblebrag on helping at the Belt and Braces. The B&B’s kitchen took care of everything, anyway. It had taken Limpopo a while to get the idea that food was applied chemistry and humans were shitty lab techs, but after John Henry splits with automat systems, even she agreed that the B&B produced the best food with minimum human intervention. And there were croissants, which was exciting!

She did squeeze the oranges herself, but only because when she peaked she liked to squeeze her hands and work the muscles in her shoulders and arms, and could get the orange hulls nearly as clean as the machine. They were blue oranges anyway, optimized for northern greenhouse cultivation, and yielded their juice eagerly. She plated everything—that, at least, was something humans could rock—and delivered it.

By the time she came out of the kitchen, there were more noobs, and one of them needed medical attention for heat exhaustion. She was just getting to grips with that—coffium was great for keeping your cool when multitasking— when more old hands came in and efficiently settled and fed everyone else. Before long, there was a steady rocking rhythm to the B&B that Limpopo fucking loved, the hum of a complex adaptive system where humans and software coexisted in a state that could be called dancing.

The menu evolved through the day, depending on the feedstocks visitors brought. Limpopo nibbled around the edges, moving from one red light to the next, till they went green, developing a kind of sixth sense about the next red zone, logging more than her share of work units. If there had been a leaderboard for the B&B that day, she’d have been embarrassingly off the charts. She pretended as hard as she could that her friends weren’t noticing her bustling activity. The gift economy was not supposed to be a karmic ledger with your good deeds down one column and the ways you’d benefited from others down the other. The point of walkaways was living for abundance, and in abundance, why worry if you were putting in as much as you took out? But freeloaders were freeloaders, and there was no shortage of assholes who’d take all the best stuff or ruin things through thoughtlessness. People noticed. Assholes didn’t get invited to parties. No one went out of their way to look out for them. Even without a ledger, there was still a ledger, and Limpopo wanted to bank some good wishes and karma just in case.

The crowd slackened around four. There were enough perishables that the B&B declared a jubilee and put together an afternoon tea course. Limpopo moved toward the reddening zones in the food prep area and found that Etcetera guy.

“Hey there, how’re you enjoying your noob’s day here at the glorious Belt and Braces?”

He ducked. “I feel like I’m going to explode. I’ve been fed, drugged, boozed, and had a nap by the fire. I just can’t sit there anymore. Please put me to work?”

“You know that’s something you’re not supposed to ask?”

“I got that impression. There’s something weird about you—I mean, us?— and work. You’re not supposed to covet a job, and you’re not supposed to look down your nose at slackers, and you’re not supposed to lionize someone who’s slaving. It’s supposed to be emergent, natural homeostasis, right?”

“I thought you might be clever. That’s it. Asking someone if you can pitch in is telling them that they’re in charge and deferring to their authority. Both are verboten. If you want to work, do something. If it’s not helpful, maybe I’ll undo it later, or talk it over with you, or let it slide. It’s passive aggressive, but that’s walkaways. It’s not like there’s any hurry.”

He chewed on that. “Is there? Is there really abundance? If the whole world went walkaway tomorrow would there be enough?”

“By definition,” she said. “Because enough is whatever you make it. Maybe you want to have thirty kids. ‘Enough’ for you is more than ‘enough’ for me. Maybe you want to get your calories in a very specific way. Maybe you want to live in a very specific place where a lot of other people want to live. Depending on how you look at it, there’ll never be enough, or there’ll always be plenty.”

While they’d gabbed, three other walkaways prepped tea, hand-finished scones and dainty sandwiches and steaming pots and adulterants arranged on the trays. She consciously damped the anxiety at someone doing “her” job. So long as the job got done, that’s what mattered. If anything mattered. Which it did. But not in the grand scheme of things. She recognized one of her loops.

“Well that settles that,” she said, jerking her chin at the people bringing out the trays. “Let’s eat.”

“I don’t think I can.” He patted his stomach. “You guys should install a vomitorium.”

“They’re just a legend,” she said. “‘Vomitorium’ just means a narrow bottle-neck between two chambers, from which a crowd is vomited forth. Nothing to do with gorging yourself into collective bulimia.”

“But still.” He looked thoughtful. “I could install one, couldn’t I? Log in to your back-end, sketch it out and start looking for material, taking stuff apart and knocking out bricks?”

“Technically, but I don’t think you’d get help with it, and there’d be reverts when you weren’t around, people bricking back the space you’d unbricked. I mean, a vomitorium is not only apocryphal—it’s grody. Not the kind of thing that happens in practice.”

“But if I had a gang of trolls, we could do it, right? Could put armed guards on the spot, charge admission, switch to Big Macs?”

This was a tedious, noob discussion. “Yeah, you could. If you made it stick, we’d build another Belt and Braces down the road and you’d have a building full of trolls. You’re not the first person to have this little thought experiment.”

“I’m sure I’m not,” he said. “I’m sorry if it’s boring. I know the theory, but it seems like it just couldn’t work.”

“It doesn’t work at all in theory. In theory, we’re selfish assholes who want more than our neighbors, can’t be happy with a lot if someone else has a lot more. In theory, someone will walk into this place when no one’s around and take everything. In theory, it’s bullshit. This stuff only works in practice. In theory, it’s a mess.”

He giggled, an unexpected, youthful sound.

“I’ve got a bunch of questions about that, but you had that so ready I’d bet you can bust out as many answers like it as you need.”

“Oh, I’m sure,” she said. She liked him, despite him being a shlepper. “Does it scale? So far, so good. What happens in the long run? As a wise person once said—”

“In the long run, we’re all dead.”

“Though who knows, right?”

“You don’t believe that tuff, do you?”

“You call it tuff, I call it obvious. When you’re rich, you don’t have to die. That’s clear. Put together the whole run of therapies—selective germ plasm optimization, continuous health surveillance, genomic therapies, preferential transplant access… If I believed in private property, I’d give you odds that the first generation of immortal humans are alive today. They will outrace and outpace their own mortality.”

She watched him try to disagree without being rude and remembered how she’d worried about offending people when she’d first gone walkaway. It was adorable.

“Just because money can be traded for lifespan to a point, it doesn’t follow that it scales,” he said. “You can trade money for land, but if you tried to buy New York City one block at a time, you’d run out of money no matter how much you started with, because as the supply decreased—” He shook his head. “I mean, not to say that there’s supply and demand when it comes to your health, but, diminishing returns for sure. Believing that science will advance at the same rate as mortality is mumbo jumbo.” He looked awkward. She liked this guy. “It’s an act of faith. No offense.”

“No offense. You missed the most important argument. Life extension comes at the expense of quality of life. There’s a guy about two hundred miles that way”—she pointed south—“worth more than most countries, who is just organs and gray matter in a vat. The vat’s in a fortified clinic and the clinic’s in a walled city. Everyone who works in that city shares that guy’s microbial nation. It’s a condition of employment. You’ve got one hundred times more nonhuman cells in your body than human ones. The people who live in that city are ninety-nine percent immortal rich-guy, extensions of his body. All they do is labor to figure out how to extend his life. Most of them went tops in their classes at the best unis in the world. Recruited out of school. Paid a wage that can’t be matched anywhere else.

“I met someone who used to work there, gave it up and went walkaway. He said the guy in the vat is in perpetual agony. Something tricked his pain perception into ‘continuous, non-adapting peak load.’ He’s feeling as much pain as is humanly possible, pain you can’t get used to. He could tell them to switch off the machines—and he’d be dead. But he’s hanging in. He’s making a bet that some super-genius in his city who’s thinking about the bounty on the bugs in this guy’s personal bug-tracker will figure out how to solve this nerve thing. There’ll be breakthroughs, if everything goes to plan. So the vat will just be his larval phase. You don’t have to believe it, but it’s the truth.”

“It’s not weirder than other stories I’ve heard about zottas. The only unlikely thing is that your buddy was able to go walkaway at all. Sounds like the kind of deal where you’d get hunted down like a dog for violating your NDA.”

She remembered the guy, who’d gone by Langerhans, all weird tradecraft stuff—dead drops and the lengths he went to in order to avoid leaving behind skin cells and follicles, wiping down his used glasses and cutlery. “He kept a low profile. As for that NDA, he had weird shit to tell, but nothing that I could have used to kickstart my own program or sabotage the man in the vat. He was shrewd. Absolutely raving bugfuck. But shrewd. I believed him.”

“It’s just like I was saying. This guy is enduring unimaginable pain because of his superstitious belief that he can spend his way out of death. The fact that this guy believes it doesn’t have any connection with its reality. Maybe this guy will spend a hundred years trapped in infinite hell. Zottas are just as good at self-delusion as anyone. Better—they’re convinced they got to where they are because they’re evolutionary sports who deserve to be exalted above baseline humans, so they’re primed to believe anything they feel must be true. What, apart from blind, self-serving faith by this zotta leads you to believe that there’s anything other than wishful thinking?”

Limpopo remembered Langerhans’s certainty, his low, intense ranting about the coming age of immortal zottas whose familial dynasties would be captained by undying tyrants.

“I admit I don’t have anything to prove it. Everything I know I learned secondhand from someone scared out of his skin. This is one of those things where it’s worth behaving as though it was true, even if it never comes to pass. The zottas are trying to secede from humanity. They don’t see their destiny as tied to ours. They think that they can politically, economically, and epidemiologically isolate themselves, take to high ground above the rising seas, breed their offspring by Harrier jets.

“I’d been walkaway for nearly a year before I understood this. That’s what walkaway is—not walking out on ‘society,’ but acknowledging that in zottaworld, we’re problems to be solved, not citizens. That’s why you never hear politicians talking about ‘citizens,’ it’s all ‘taxpayers,’ as though the salient fact of your relationship to the state is how much you pay. Like the state was a business and citizenship was a loyalty program that rewarded you for your custom with roads and health care. Zottas cooked the process so they get all the money and own the political process, pay as much or as little tax as they want. Sure, they pay most of the tax, because they’ve built a set of rules that gives them most of the money. Talking about ‘taxpayers’ means that the state’s debt is to rich dudes, and anything it gives to kids or old people or sick people or disabled people is charity we should be grateful for, since none of those people are paying tax that justifies their rewards from Government Inc.

“I live as though the zottas don’t believe they’re in my species, down to the inevitability of death and taxes, because they believe it. You want to know how sustainable Belt and Braces is? The answer to that is bound up with our relationship to the zottas. They could crush us tomorrow if they chose, but they don’t, because when they game out their situations, they’re better served by some of us ‘solving’ ourselves by removing ourselves from the political process, especially since we’re the people who, by and large, would be the biggest pain in the ass if we stayed—”

“Come on.” He had a good smile. “Talk about self-serving! What makes you think that we’re the biggest pains? Maybe we’re the easiest of all, since we’re ready to walk away. What about people who’re too sick or young or old or stubborn and demand that the state cope with them as citizens?”

“Those people can be most easily rounded up and institutionalized. That’s why they can’t run away. It’s monstrous, but we’re talking about monstrous things.”

“That’s creepy,” he said. “And cinematic. Do you really think zottas sit around a star chamber plotting how to separate the goats from the sheep?”

“Of course not. Shit, if they did that, we could suicide-bomb the fuckers. I think this is an emergent outcome. It’s even more evil, because it exists in a zone of diffused responsibility: no one decides to imprison the poor in record numbers, it just happens as a consequence of tougher laws, less funding for legal aid, added expense in the appeals process… There’s no person, decision, or political process you can blame. It’s systemic.”

“What’s the systemic outcome of being a walkaway, then?”

“I don’t think anyone knows yet. It’s going to be fun finding out.”

Excerpted from Walkaway, copyright © 2017 by Cory Doctorow