In the trenches of Europe during the Great War, Tomás Cordero operated a weapon more devastating than any gun: a flame projector that doused the enemy in liquid fire. Having left the battlefield a shattered man, he comes home to find yet more tragedy—for in his absence, his wife has died of the flu. Haunted by memories of the woman he loved and the atrocities he perpetrated, Tomás dreams of fire and finds himself setting match to flame when awake….

Alice Dartle is a talented clairvoyant living among others who share her gifts in the community of Cassadaga, Florida. She too dreams of fire, knowing her nightmares are connected to the shell-shocked war veteran and widower. And she believes she can bring peace to him and his wife’s spirit.

But the inferno that threatens to consume Tomás and Alice was set ablaze centuries ago by someone whose hatred transcended death itself…

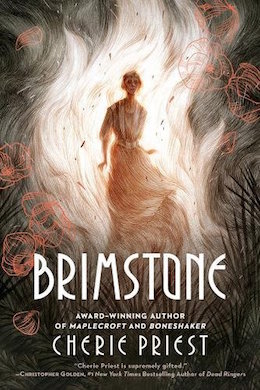

Cherie Priest’s new dark historical fantasy Brimstone is available April 4th from Ace Books—read an excerpt below!

Chapter 1

Alice Dartle

Aboard the Seaboard Express,

bound for Saint Augustine, Florida

January 1, 1920

Last night, someone dreamed of fire.

Ordinarily I wouldn’t make note of such a thing in my journal—after all, there’s no subject half so tedious as someone else’s dream. One’s own dream might be fascinating, at least until it’s described aloud—at which point one is inevitably forced to admit how ridiculous it sounds. But someone else’s? Please, bore me with the weather instead.

However, this is a long train ride, and I have finished reading the newspaper, my book, and both of the magazines I put in my bag for the trip. Truly, I underestimated my appetite for the printed word.

It’s a circular thing, this tedium, this nuisance of rolling wheels on a rumbling track and scenery whipping past the window, because my options are miserably limited. Once I’m out of reading material, there’s nothing to do but sit and stare, unless I want to sit and write something to sit and stare at later on. So with that in mind, here I go—nattering to these pages with a pencil that needs sharpening and an unexpected subject on my mind: There was a man, and he dreamed of fire, and I could smell it as if my own hair were alight.

Whoever he was, this man was lying on a bed with an iron frame, listening to the foggy notes of a phonograph playing elsewhere in his house. Did he forget to turn it off? Did he leave it running on purpose, in order to soothe himself to sleep? I didn’t recognize the song, but popular music is a mystery to me, so my failure to identify the title means nothing.

This man (and I’m sure it was a man) was drifting in that nebulous space between awake and a nap, and he smelled the dream smoke so he followed it into something that wasn’t quite a nightmare. I must say it wasn’t quite a nightmare, because at first he was not at all afraid. He followed the smoke eagerly, chasing it like a lifeline, like bread crumbs, or, no—like a ball of yarn unspooled through a labyrinth. He clutched it with his whole soul and followed it into the darkness. He tracked it through halls and corridors and trenches… yes, I’m confident that there were trenches, like the kind men dug during the war. He didn’t like the trenches. He saw them, and that’s when the dream tilted into nightmare territory. That’s when he felt the first pangs of uncertainty.

Whatever the man thought he was following, he did not expect it to lead him there.

He’d seen those trenches before. He’d hidden and hunkered, a helmet on his head and a mask on his face, crouched in a trough of wet dirt while shells exploded around him.

Yes, the more I consider it—the more I pore over the details of that man’s dream, at least as I can still recall them—the more confident I am: Whoever he is, he must be a soldier. He fought in Europe, but he isn’t there anymore. I do not think he’s European. I think he’s an American, and I think our paths shall cross. Sooner rather than later.

I don’t have any good basis for this string of hunches, but that’s never stopped me before, and my hunches are usually right. So I’ll go ahead and record them here, in case the particulars become important later.

Here are a few more: When I heard his dream, I heard seabirds and I felt a warm breeze through an open window. I smelled the ocean. Maybe this man is in Florida. I suspect that I’ll meet him in Cassadaga.

How far is Cassadaga from the Atlantic? I wonder.

I looked at a map before I left Norfolk, but I’m not very good at maps. Well, my daddy said there’s no place in Florida that’s terribly far from the water, so I’ll cross my fingers and hope there’s water nearby. I’ll miss the ocean if I’m ever too far away from it.

I already miss Norfolk a bit, and I’ve been gone only a few hours. But I’ve made my choice, and I’m on my way. Soon enough, I’ll be in Saint Augustine, and from there, I’ll change trains and tracks—I’ll climb aboard the Sunshine Express, which will take me the rest of the way. It will drop me off right in front of the hotel. Daddy made sure of it before he took me to the station.

Mother refused to come along to see me off. She says I’m making an awful mistake and I’m bound to regret it one of these days. Well, so what if I do? I know for a fact I’d regret staying home forever, never giving Cassadaga a try.

She’s the real reason I need to go, but she doesn’t like it when I point that out. It’s her family with the gift—or the curse, as she’d rather call it. She’d prefer to hide behind her Bible and pretend it’s just some old story we use to scare ourselves at Halloween, but I wrote to the library in Marblehead, and a man there wrote me back with the truth. No witches were ever staked and torched in Salem—most of them were hanged instead—but my aunts in the town next door were not so lucky.

The Dartle women have always taken refuge by the water, and they have always burned anyway.

Supposedly, that’s why my family left Germany ages ago—and why they moved from town to town, to rural middles of nowhere for so long: They were fleeing the pitchforks and torches. How we eventually ended up in Norfolk, I don’t know. You’d think my ancestors might have had the good sense to run farther away from people who worried about witches, but that was where they finally stopped, right on the coast, where a few miles north the preachers and judges were still calling for our heads. They were hanging us up by our necks.

Even so, Virginia has been our home for years, but I, for one, can’t stay there. I can’t pretend I’m not different, and our neighbors are getting weird about it.

I bet that when I’m good and gone, my mother will tell everyone I’ve headed down to Chattahoochee for a spell, to clear my head and get right with God. As if that’s what they do to you in those kinds of places.

Mother can tell them whatever she wants. Daddy knows the truth, and he’s wished me well.

Besides, what else should I do? I’m finished with my schooling, and I’m not interested in marrying Harvey Wheaton, because he says I have too many books. Mother said it was proof enough right there that I was crazy, if I’d turn down a good-looking boy with a fortune and a fondness for a girl with some meat on her bones, but Daddy shrugged and told me there’s a lid for every pot, so if Harvey isn’t mine, I ought to look elsewhere. The world is full of lids.

Harvey did offer me a very pretty ring, though.

I’m not saying I’ve had any second thoughts about telling him no, because I haven’t—but Mother’s right about one thing: All the girls you see in magazines and in the pictures… they’re so skinny. All bound-up breasts and knock-knees, with necks like twigs. Those are the kinds of women who marry, she says. Those women are pretty.

Nonsense. I’ve seen plenty of happily married women who are fatter than I am.

So I’m not married. Who cares? I’m pretty, and I’m never hungry. There’s no good reason to starve to fit in your clothes when you can simply ask the seamstress to adjust them. That’s what I say. Still, I do hope Daddy’s right about lids and pots. I’m happy to be on my own for now, but someday I might like a family of my own.

And a husband.

But not Harvey.

If I ever find myself so low that I think of him fondly (apart from that ring; he said it was his grandmother’s), I’ll remind myself how he turned up his nose at my shelves full of dreadfuls and mysteries. Then I’ll feel better about being an old maid, because there are worse things than spinsterhood, I’m quite certain. Old maids don’t have to put up with snotty boys who think they’re special because they can read Latin, as if that’s good for anything these days.

I’m not a spinster yet, no matter what Mother says. I’m twenty-two years old today, and just because she got married at seventeen, there’s no good reason for me to do likewise.

She’s such an incurious woman, I almost feel sorry for her—much as I’m sure she almost feels sorry for me. I wish she wouldn’t bother.

I have some money, some education, and some very unusual skills—and I intend to learn more about them before I wear anybody’s ring. If nothing else, I need to know how to explain myself. Any true love of mine would have questions. Why do I see other people’s dreams? How do I listen to ghosts? By what means do I know which card will turn up next in a pack—which suit and which number will land faceup upon a table? How do I use those cards to read such precise and peculiar futures? And pasts?

I don’t know, but I am determined to find out.

So now I’m bound for Cassadaga, where there are wonderful esoteric books, or so I’m told. It’s not a big town, but there’s a bookstore. There’s also a hotel and a theater, and I don’t know what else. I’ll have to wait and see.

I am not good at waiting and seeing.

Patience. That’s one more thing I need to learn. Maybe I’ll acquire some, with the help of these spiritualists… these men and women who practice their faith and explore their abilities out in the open as if no one anywhere ever struck a match and watched a witch burn.

Are the residents of Cassadaga witches? That’s what they would’ve been called, back when my however-many-great-great-aunts Sophia and Mary were killed. So am I a witch? I might as well be, for if I’d been alive in the time of my doomed relations, the puritans at Marblehead would’ve killed me, too.

It’s not my fault I know things. I often wish that I didn’t.

Sometimes—though of course I’d never tell him so—I tire of Daddy thrusting the newspaper before me, asking which stocks will rise or fall in the coming days. It’s ungenerous of me, considering, and I ought to have a better attitude about it. (That’s what my sister says.) My stock suggestions helped my parents purchase our house, and that’s how I came by the money for this trip, too. Daddy could hardly refuse me when I told him I wanted to learn more about how to best make use of my secret but profitable abilities.

I went ahead and let him think I’ll be concentrating on the clairvoyant side of my talents, for he’s squeamish about the ghosts. Whenever I mention them, he gently changes the subject in favor of something less gruesome and more productive… like the stock sheets.

Or once, when I was very small, he brought up the horses at a racetrack. I don’t think he knows I remember, but I do, and vividly: They were great black and brown things, kicking in their stalls, snorting with anticipation or snuffling their faces in canvas feed bags. The barn reeked of manure and hay and the sweaty musk of big animals. It smelled like leather and wood, and soot from the lanterns. It smelled like money.

He asked me which horse would win the next race, and I picked a tea-colored bay. I think she won us some money, but for some reason, Daddy was embarrassed by it. He asked me to keep our little adventure from my mother. He made me promise. I don’t know what he did with our winnings.

We never went to the races again, and more’s the pity. I liked the horses better than I like the stock sheets.

I hear there are horse tracks in Florida, too. Maybe I’ll find one.

If there’s any manual or course of instruction for my strange abilities, I hope to find that in Florida, too. I hope I find answers, and I hope to find people who will understand what I’m talking about when I say that I was startled to receive a dream that didn’t belong to me.

So I’ll close this entry in my once rarely used (and now excessively scribbled upon) journal precisely the way I began it—with that poor man, dreaming of fire. That sad soldier, alone in a house with his music, and the ocean air drifting through the windows. He’s bothered by something, or reaching out toward something he doesn’t understand. He’s seeking sympathy or comfort from a world that either can’t hear him or won’t listen.

I hear him. I’ll listen.

Mother says that an unmarried woman over twenty is a useless thing, but I am nowhere near useless, as I’ve proved time and time again—in the stock sheets and (just the once) on the racetracks. Well, I’ll prove it in Cassadaga, too, when I learn how to help the man who dreams of fire.

Chapter 2

Tomás Cordero

Ybor City, Florida

January 1, 1920

The police must have called Emilio. Perhaps some policy requires them to seek out a friend or family member in situations like this—when a man’s sanity and honesty are called into question, and public safety is at risk. I understand why the authorities might have their doubts, but no one was harmed. No real damage was done. I remain as I have always been since my return: rational, nervous, and deeply unhappy. But that’s nothing to do with the fire.

My friend and right-hand fellow—the young and handsome Emilio Casales—sat in my parlor regardless, wearing a worried frown and the green flannel suit he’d finished crafting for himself last week. His waistcoat was a very soft gray with white pinstripes, and his neck scarf was navy blue silk. Bold choices, as usual, but well within the bounds of taste.

Emilio is not a tall man, but he’s slender and finely shaped. He wears his new suit well. He wears everything well. That’s why he has the run of my front counter.

Alas, he had not come to talk about clothes or the shop. He was there because the police had questions and they weren’t satisfied with my answers. I’d told them all the truth—from sharply uniformed beat officer to sloppily geared fire chief. But any fool could tell they did not believe me.

Emilio did not believe me, either.

“It was only a little fire,” I assured him. “It was discovered swiftly, then the truck came, and now it’s finished. You know, I’d been meaning to repaint the stucco for quite some time. Now I am graced by a marvelous soot and water stain on my eastern wall… and that’s a good an excuse, don’t you think?”

He was so earnest, so sweet, when he asked me for the hundredth time, “But, Tomás, how did it begin? The chief said the fire began in a palmetto beside the back door. I’ve never heard of one simply… bursting into flames.”

We were speaking English, out of respect for the Anglo fireman who lingered nearby with his paperwork. The chief and the cops were gone, but they’d left this man behind—and he was listening, but he was polite enough to pretend otherwise.

“It must have been my own doing, somehow. Or maybe it was Mrs. Vasquez from the house behind me. Either one of us could have tossed a cigarette without thinking. It’s been so dry these last few weeks.” The winter weather had been a surprise—we’ve seen little rain since November, and it’s been so warm, even for the coast. “There are leaves and brush, and… it wouldn’t take much. Apparently, it didn’t take much.”

Emilio lifted a sharp black eyebrow at me. “A cigarette? That’s your excuse?”

He was right. It wasn’t a very good one. I rattled off some others, equally unlikely, but ultimately plausible. “Ashes from the stove—do you like that better? A spark from a lantern? Trouble with the fixtures? God knows I have no idea how those electrical lines work, or where they’re located. It might as well be magic, running through the house unseen.”

“Tomás.” He leaned forward, his fingers threaded together. “It’s your third fire in a month.”

I lifted a finger. “My third harmless fire. They’re silly things, aren’t they? One in the trash bin, one in the washroom. Now this one, outside. It scorched the wall, and nothing else. You worry too much, my friend.”

The fireman cleared his throat. “You should have a man from the electric company check the fuses. If only to rule them out, or diagnose the problem—and fix it before the house comes down around your ears.”

“Yes!” I agreed. I was too merry and swift about it, I’m sure. “That’s a wonderful suggestion. One can never be too cautious when dealing with electrical power; the technology is too new, and sometimes I worry for how little I understand its mechanisms. But it’s too late to call upon the office this afternoon. I’ll do it tomorrow.”

“Good plan.” He nodded, closing his notebook. “I’d hate to come out here a fourth time. My father would never forgive me if I let you go up in smoke.”

“I’m sorry, come again?”

He tucked a pen into his front breast pocket. “He wore one of your suits to my wedding. He says you’re an artist.”

I’m sure I blushed. “Why, thank you. And thank your father, as well. Could I ask his name?”

“Robert Hunt. You made him a gray wool three-piece, with four buttons and doubled flap pockets, back before… before you went to war. I doubt you’d remember it. He could only afford the one suit,” he added bashfully. “A simple model, but one for the ages; that’s what he’ll tell you. He still pulls it out for special occasions.”

I turned the name over in my head. “Was he a brown-eyed man with gold hair, fading to white? I believe he had a tattoo…”

Now the fireman was surprised. “Good God, that’s him!”

I warmed to the memory of wool between my fingers. The fabric was thicker back then, even a few years ago. The styles, the material… it’s all gone lighter now, and more comfortable for men like us, near the tropics. “I never forget a suit, though my grasp of names is not so good. You reminded me with the details and the bit about the wedding. Your father, he had been in the service. Yes?”

“Yes, Mr. Cordero. Back in ’ninety-eight. The tattoo… it was a flag, on his right arm.” He tapped his own forearm to show me where he meant.

“I saw it when I measured him.” I nodded. Then, to Emilio, I said, “This was before you and your brother joined me. Back then, I had my Evelyn to help with the cutting and sewing.”

It never gets easier to say her name, but with practice and habit I can make it sound effortless. I can make it sound like I’ve fully recovered, scarcely a year since I came home from the front and they told me she was dead from the flu. She was buried in a grave with a dozen others, on the outside of town. Perhaps it was this grave, in this place—or maybe it was that grave, in some other quarter. No one was certain. So many graves had been dug, you see. So many bodies had filled them up, as fast as the shovels could dig. The whole world was crisscrossed with trenches and pits, at home and abroad. If the dead were not felled by guns, then they were swept away by illness.

It was just as well that I went to war. There was no safety in staying behind.

“My Evelyn,” I repeated softly, testing the sound of it. My voice hadn’t broken at all this time. Hers could have been any name, fondly recalled but no longer painful.

What a pretty lie.

She and I said our good-byes when I went to Europe, but those farewells were in no way adequate for her absolute departure; and now, I cannot even lay claim to her mortal remains. I can only pray toward her ephemeral, lost spirit. I don’t have so much as a tedious, cold headstone in a proper garden of the remembered dead. Not even that.

“Tomás?” Emilio placed a hand upon my knee.

I didn’t realize I’d gone so silent. “I’m sorry. My head is aching, that’s all. I’m very tired.”

“Are you feeling well? Can I get you your pills?”

“It’s not so bad. Only the same old thing… the war strain.” I chose a term I liked better than “shell shock.” “Sometimes it makes my head feel full, and foggy. Or it might only be the smell of the smoke, you know. There was so much smoke in the war.”

Both Emilio and the fireman, whose name I never caught, finally accepted this explanation—at least in part. I settled for this small victory. I declined the pills, which were only French aspirin anyway, and wouldn’t have helped at all. I urged them both to leave me, that I might settle in and make myself dinner.

I wasn’t hungry, and I didn’t plan to make dinner. But Emilio wouldn’t depart until I’d assured him otherwise. He is worried, I know. He brings me candies and fruit empanadas with guava and cheese, like he wishes to fatten me up.

I do confess that I’ve lost a few pounds. Or more than that. I know my own measurements, and my clothes droop from my shoulders as they would from a wooden hanger. I’d rather not admit it, but there it is.

By the time they were gone, the shadows had stretched out long enough to leave the house darkened, so I turned on some lights. Despite what I’d told my visitors, I wasn’t really afraid of the electricity or the bulbous glass fuses in the wall. Oh, I’d keep my promise and visit the office downtown, and I’d ask for a man to test them all; it would keep Emilio and his brother appeased (as well as the fireman and anyone else who might have an interest)… but whatever was happening, it had little to do with that impressive technology.

I couldn’t share my true suspicions about the fires.

God in heaven, they’d put me away.

Excerpted from Brimstone copyright © 2017 by Cherie Priest