Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

Today we’re looking at F. Marion Crawford’s “The Upper Berth,” first published in The Broken Shaft: Unwin’s Annual for 1886. Spoilers ahead.

“I remember that the sensation as I put my hands forward was as though I were plunging them into the air of a damp cellar, and from behind the curtains came a gust of wind that smelled horribly of stagnant sea-water. I laid hold of something that had the shape of a man’s arm, but was smooth, and wet, and icy cold.”

Summary

A group of gentlemanly diners grow weary of the usual postprandial chat about sport, business and politics. Just as the party’s breaking up, Brisbane speaks. He’s a man’s man, tall and broad and muscular, and his voice has a timbre that commands attention. “It is very singular,” he says, “that thing about ghosts. People are always asking whether anybody has seen a ghost. I have.”

Ennui evaporates, and Brisbane proceeds with his tale. A frequent sailor across the Atlantic, he has his favorite ships, among them the Kamtschatka. Or, rather, the Kamtschatka was once a favorite. Now nothing would induce him to sail aboard her.

His last voyage, he’s booked in State-Room 105, lower berth. The steward seems surprised Brisbane will be staying there and doubtful he can make him comfortable. Nevertheless, Brisbane settles in.

He hopes he’ll have the room to himself, but after he’s abed, a thin and colorless man of uncertain fashion enters and takes the upper berth. Later that night, the man’s leap from the upper berth wakes Brisbane. What can be wrong with the fellow to fumble open the state-room door and race up the passage as if for his life? He must return while Brisbane dozes again, because the second time Brisbane wakes, it’s to hear tossing and groans from the upper berth. His room-mate sounds sea-sick; to be sure, there’s a sudden unpleasant smell of ocean and damp.

The smell’s gone next morning. Someone’s hooked open the porthole, odd. The upper berth curtains remain closed. Brisbane goes out on deck, where he meets the ship’s doctor and mentions the shameful damp in 105. The doctor’s disturbed to hear Brisbane’s in that state-room, for its last three occupants have all gone overboard. Brisbane better pack up and move in with the doctor for the rest of the trip.

Brisbane says he’ll stay put. Later the captain tells him his room-mate’s gone missing—presumably overboard. He hopes Brisbane won’t mention this, as suicide gives a ship such a bad reputation. Come stay in the captain’s own cabin.

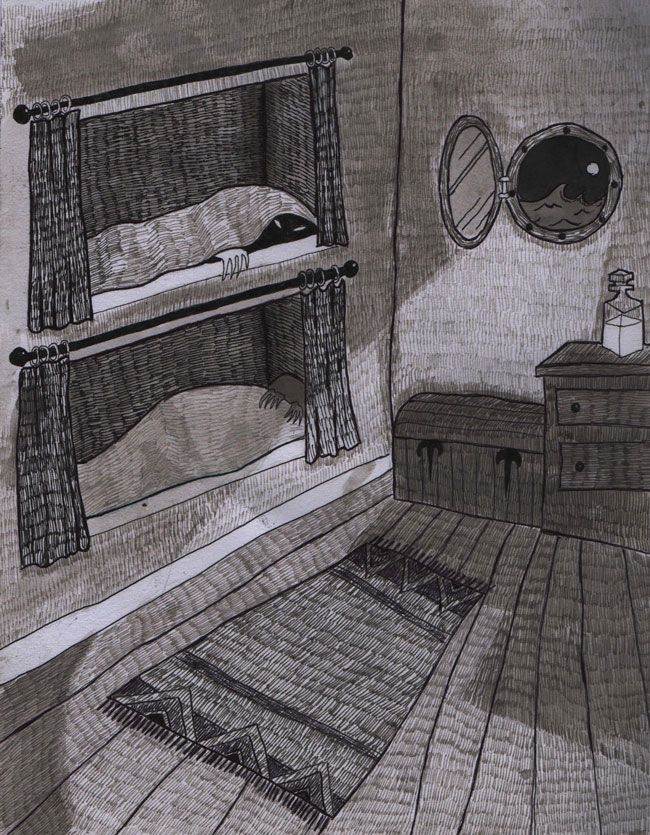

Though Brisbane again declines other quarters, he’s nervous enough that night to bolt the door and peek into the empty upper berth. Then he notices the porthole’s hooked open again. He castigates the steward, who claims no one can keep that porthole closed, as Brisbane will soon see for himself. And sure enough, Brisbane wakes to see the porthole open. He closes it. Something moves in the upper berth behind him. He thrusts a hand through the curtains, smells stagnant seawater, grabs a man’s arm, wet and ice-cold. A “clammy, oozy mass,” the intruder pushes past Brisbane and escapes out the door.

Next day Brisbane asks doctor and captain to spend a night in 105 and help him solve the mystery of the nocturnal disturbance. The doctor cries off; the captain agrees. First they have the ship’s carpenter examine the state-room for hidden panels, uncovering none. The carpenter’s advice is for Brisbane to clear out and let him drive screws into the door, shutting it permanently.

That night the captain plants himself in front of the bolted door, while Brisbane watches the securely fastened porthole. While they wait, the captain confides that the first of the 105 suicides was a runaway lunatic whose body was never recovered from the sea.

Both Brisbane and the captain notice the porthole loop-nut turning slowly on its screw. They smell seawater. Their lamp goes out, and their combined efforts can’t halt the accelerated opening of the porthole. It swings inward. The captain retreats to the door. Something’s in the upper berth, he cries.

Brisbane springs to the berth curtains. This time, in light from the passage, he clearly sees the intruder: “the dead white eyes seemed to stare at [him] out of the dusk; the putrid odor of rank seawater was about it, and its shiny hair hung in foul wet curls over its dead face.” It grapples with Brisbane, wrapping “corpse’s arms” around his neck. He falls, and the thing turns to the captain, who strikes it before falling himself. To Brisbane’s “disturbed senses,” the thing exits the porthole, which should be too small for it to fit through.

The captain’s unhurt but stunned. Brisbane’s left forearm’s broken. The doctor sets it and makes room for Brisbane in his cabin, while the carpenter gets his wish: He screws shut the door of State-Room 105.

The Kamtschatka’s still in service, though the captain never sailed on her again. But if you try to engage 105, you’ll be told it’s already engaged. Yes, Brisbane concludes. It’s engaged by a certain ghost, if ghost it was. It was dead, anyhow.

What’s Cyclopean: Cold, clammy, damp, putrid… this is certainly a ghost to chill Lovecraft’s own aquaphobic heart.

The Degenerate Dutch: Brisbane suggests that the Kamtschatka’s “washing apparatus” would “convey an idea of luxury to the mind of a North American Indian.” To be fair, this isn’t nearly as pointed as some of the comments about European cleanliness that historians record from said Indians following initial contact.

Mythos Making: The squirmy dead thing might be distant ancestor to a few of Lovecraft’s revenants.

Libronomicon: No books this week.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The first passenger lost to Cabin 105, says the captain, “turned out to be a lunatic.”

Ruthanna’s Commentary

And here we have a comfortingly old-fashioned ghost story. I suspect it was already old-fashioned in 1894. But originality isn’t the point of this sort of thing—it’s the sort of yarn that’s induced pleasant shivers at late-night parties for centuries. Indeed, it’s framed as just that. Like Wells’s Time Traveler, Brisbane shares his unlikely adventures over cigars and cognac with a few gentlemen of his acquaintance. His host, much more frightened by the thought of interminable conversation with his less delightful guests than by ghosts, heaves a sigh of relief.

So that’s our scene-setter, and an indication of the story’s goal—not terror or hiding under the bed, but pleasantly mild shivers on a safe warm night, far from any danger. There are nights when that’s all you want.

The hazard is eased by the fact that, throughout, it’s Brisbane’s choice to stay in the cabin. He’s never stuck; he’s the exact equivalent of the skeptical investigator spending the night in a haunted house. Once he has a real idea that something’s going on, he’s not even alone. The ship’s captain, like him a brave and determined man of action, has his back. The ghost is certainly dangerous, having killed three people already with the misfortune to share its mattress, but the guy in the lower berth just gets a nasty draught, a fractured wrist, and a fistful of goo.

As clever as he is at spinning out a ghost story, Brisbane’s nearly as good at kvetching. He has down the balance between complaining about everything, and convincing you that he only noticed these imperfections for entertainment’s sake. He’s an old sailor, after all—what should it matter to him if the bar is stocked with brown water and the toothbrush holder has been confused with an umbrella stand? In that context, ghostly bunkmates are just another hazard of the crossing.

Lovecraft seems to have enjoyed this story too, and one can see at least mild influences. The narrator motivated by curiosity and bravery, rather than forced into the situation, introduces us to any number of eldritch entities. The foolhardy thrill-seeking investigator of “The Lurking Fear” might be a relation, and “Horror in the Museum” involves a similar willingness to sit up late waiting for creepy things.

The ghost itself is… maybe something more, or at least different, than a ghost. “It was dead, anyway,” gets points for a succinct yet thought-provoking final line. Whatever the critter is, it’s tangible, capable not only of sliming you but getting into a wrestling match. The possibilities are endless. Siren with a sore throat, reduced to drowning sailors directly? Deep One irked at the Kamtschatka for its role in polluting the ocean? Drowned corpse, come back to the ship for a decent night’s rest?

Maybe with modern air conditioning, it could just enjoy the voyage like everyone else.

Anne’s Commentary

Francis Marion Crawford was born in Italy, studied in Cambridge and Heidelberg and Rome, hobnobbed with illustrious Boston relations like Julia Ward Howe, studied Sanskrit in India, sang well enough to entertain operatic ambitions, and finally settled back in Italy to write novels, histories and some exceptional horror tales. With a bio like that, he must have known something about late 19th and early 20th-century travel. “Berth’s” protagonist Brisbane is another such seasoned wanderer. I can imagine him in the smoking lounge of a transatlantic steamer, chatting companionably with Mark Twain’s innocent abroad and Sinclair Lewis’s Sam Dodsworth, that most stolid, thoughtful and romantic of Old World-bound American tourists. Dodsworth might have been one of the sleepy diners of “Berth’s” opening, hearing for the hundredth time the usual masculine gossip about hunting, business shenanigans, and politics. Mention of a ghost would have cheered him up, too, especially a thoroughly modern ghost determined to haunt a topflight steamer rather than a dowdy old manse or dungeon.

Lovecraft considered “The Upper Berth” Crawford’s weird masterpiece and “one of the most tremendous horror-stories in all literature.” That would have to equal five stars on Amazon or Goodreads, right? I have a slightly softer spot for Crawford’s “For the Blood is the Life,” because great title and vampire and highly desirable setting on the Calabrian coast. But no denying, “Berth” takes full advantage of the traveling person’s occasional qualms about who might have occupied his or her hired bunk before. One’s bed—and bedchamber—is one’s nest, one’s den, one’s lair and sanctuary. No wonder we shudder at the thought of its invasion, whether by something as mundane as a spider or mouse or by something as uncanny as Crawford’s dead thing. No wonder, therefore, that ghosts love nothing better than pouncing on a victim securely tucked under the bedclothes. Beds with curtains around them may seem cozy-chic during the day, but at night they’re a huge temptation to all things supernatural and malign.

Say you’re a ghoul. What could be more fun than to trail your bony fingers over the outside of the bed-curtains, making them sway and billow, rustle and sigh? You hear a nervous squeak from the occupant. Perfect time to slip one of those bony fingers through the curtains, preparatory to tearing them open and revealing your whole unspeakable self!

“Berth” actually reverses this classic situation. It’s the dead thing that’s tucked into bed and the living who disturb its restless repose. This ghost (let’s call him Bertie) is an interesting fellow. We never learn his history for sure, but let’s conclude (as the captain and Brisbane seem to do) that he’s the first of the State-Room 105 casualties, a madman run off from his friends. He goes overboard, and his body’s never recovered. Authorities rule Bertie’s death a suicide, which is a rare thing according to the captain. One would never expect the next three cruises to feature a similar suicide, and one committed in each case by the occupant of State-Room 105!

It must be Bertie’s fault, because the suicide-cluster started with him. But does he necessarily intend to scare 105 occupants to death? In other words, is he a malicious apparition? I’m thinking not. I’m thinking he just wants to get a good night’s sleep in the upper berth he paid for. If someone else happens to be there, oh well, why can’t they share instead of freaking out and jumping off the ship? Maybe Bertie radiates psychic reverberations of his last moments so powerful that they infect his accidental bedmates, causing them to imitate his dramatic exit. Too bad, but what’s he supposed to do about that? Sleep under the cold waves forever?

Tellingly, Bertie never deliberately bothers Brisbane, occupant of the lower berth. That first night, after the tall man cedes Bertie’s place, Bertie ignores his other room-mate. His groaning and tossing and smell are impositions he can’t help. He only attacks when attacked, twice by Brisbane manfully thrusting his manly arms into the upper berth, once when the captain blocks his escape out the state-room door.

Maybe Brisbane is right to ponder whether he saw a ghost, per se. Bertie has some too-too solid (though slimy and icy) flesh to him, and (like Brisbane himself, though in quite a different manner) he’s much stronger than he looks. Fast, too, and slug-squishable enough to squeeze through the porthole. No transparency or translucency about Bertie, and no putting your hand right through him. He’s more reanimated corpse than spirit, rather like the protagonist of Lovecraft’s “Outsider.” And like the Outsider, he may just be too oblivious or stubborn to realize he’s dead.

I like to imagine Bertie clinging to the keel of the Kamtschatka all day, pickling nicely in the brine. At night he has only to claw his way up to the porthole of 105, open it with preternatural strength, and squirm inside.

All anyone ever had to do was leave the upper berth empty. Screwing shut the door to 105, an even better idea. Again like Brisbane, Bertie prefers a private room, and now he’s got one for as long as that topflight steamer Kamtschatka continues to ply the deep blue.

Happy ending all around. Bertie gets his uninterrupted beauty sleep and Brisbane gets a story to enliven the most moribund of gatherings!

Next week, Amelia Gorman’s “Bring the Moon to Me,” from She Walks in Shadows, shows that you can still get in quite a bit of trouble with non-Euclidean mathematics.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.