Amazon’s adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle was a surprise hit last year, quickly becoming one of the streaming service’s most popular shows. This season saw the departure of showrunner Frank Spotnitz, which led to a messier show, but overall The Man in the High Castle was a powerful meditation on fascism, family, intellectual freedom, and whether survival alone can ever count as a victory.

The season opens on Obergruppenführer John Smith’s son Thomas heading off for his day at Fritz Julius Kuhn High School, and leading everyone in the Pledge. Fritz Julius Kuhn was the head of the German American Bund, a group who tried to convert Americans to Nazism and held a horrifyingly popular rally at Madison Square Garden in 1939. In our reality he was sent to prison for embezzling money from the Bund, but in Thomas Smith’s he’s a hero of the Reich, and the Pledge the kids recite is a declaration of lifelong devotion to Adolph Hitler.

Light spoilers follow.

As we begin the new season, the three main characters, Juliana Crain, Frank Frink, and Joe Blake, are separated. Joe grapples with learning his father’s true identity, rethinks his Nazism, and comes to terms with Juliana’s choice to save his life. Juliana defects over to the Greater Nazi Reich to escape the Resistance, despite hating the Nazis. And Frank, thinking Juliana betrayed him for Joe, is drawn deeper into the Resistance cause when he tries to save his friend Ed, who took responsibility for the attempt on the Japanese Crown Prince’s life. (It was a busy season.) But the problems of three people don’t add up to a hill of beans in Philip K. Dick’s crazy, mixed up timeline, as we soon see.

We spend far more time with Obergruppenführer John Smith and his family, Trade Minister Tagomi and Chief Inspector Kido, and with the Resistance on both coasts. This was a great way to force the audience to look beyond the lives of the three leads of Season One and see the larger implications of the Axis victory. The shading becomes far more interesting as the season goes on. Resistance leaders turn out to be violent, short-sighted egomaniacs. Nazis are loving fathers. Trade Minister Tagomi, a soft-spoken, gentle man in the show’s main timeline, is revealed to be a vindictive drunk in our own world. And where the first season was a thriller about the Resistance, this season is a meditation on family, patriotism, and empathy.

In Season One, we see Juliana Crain in her daily life in San Francisco, and while she hates being in an occupied nation, she genuinely loves Japanese culture. But later on in the series when she tries to plead with the Japanese Officer Kido, he slaps her across the face for daring, as a white woman, to speak before a Japanese man has given her permission to do so. We see an even more chilling brutality when she defects to the Reich. As she can’t prove she’s Aryan, her head is measured, color swatches are held up against her skin and hair, she is stripped, x-rayed, and forced to have a pelvic exam. In the Reich, all humans are the sum of their physical traits and little more, and women are judged as breeding material before all else. If she can’t pass all of her physicals and produce racially pure children the Nazis will have no use for her, so why bother allowing her in? But after that humiliation, when Juliana is deemed acceptable and allowed a temporary visa, Helen Smith assures her that the Reich is “someplace where people actually look out for one another.” She introduces her to her friends, a social circle that would be comfortable on Mad Men… except instead of seething with casual racism, when the ladies discover that one of their nannies is a Semite they report her for extermination. Juliana finds that although most people in the Reich live under a strict stipend for clothing, Helen’s friend Alice married well enough that she can get the latest fashions (straight from Frankfurt!), and her re-education includes an emphasis on her own racial superiority over her former Japanese rulers, along with lessons on the United States’ enslavement of African-Americans, and the genocide of Native Americans.

Over on the West Coast, we meet a Resistance leader who grew up in Manzanar, the Japanese Internment Camp. While in our timeline Japanese Internment camps are defended in letter to The New York Times, in hers, she is seen as a traitor to Japan for growing up in America, and traitor to the former United States because of her Japanese heritage. She has higher status than the white citizens, and can pass as full-Japanese if she chooses to dress a certain way and use a precise accent, but she knows that the Japanese who occupy the Pacific States hate her as much as they hate the rest of the former Americans.

And finally, in Berlin, we spend time with the Lebensborn, the products of a Nazi breeding program. (In our world, the Lebensborn were persecuted by many post-Nazi governments, and the program was also accused of kidnapping thousands of children for “re-education”.) In the world of the show, the Lebensborn are the hyper-privileged members of an affluent, idealistic generation, who throw parties and shirk responsibility while they wait for the “fossils”—the elderly heads of the Reich—to die off. But what future do they want? Some of them spout environmentalist slogans that wouldn’t be out of place on a Greenpeace leaflet, but do they also buy into eugenic theory and the racism central to Nazism?

That issue provides the spine of the Smith family’s plotline. Early in the previous season it was revealed that Smith’s son has Muscular Dystrophy. If he was born in our world he’d be given medical treatment, and even in the show’s Pacific States he’d be allowed to live, but in the Reich? He’s a “defective”, a “useless eater”, and he’ll be exterminated as soon as the government learns of his condition. Not only that—since his uncle also had the condition, it’s likely that his sisters will be deemed unfit to have families of their own rather than risk them passing on imperfections. That is, if the Reich finds out. Smith spends considerable time hiding the truth from his son and the rest of the world, but he also claims an absolute belief in the Reich. He’s willing to torture and kill for it, and seems to buy into the idea of racial purity at Nazism’s heart. At a key point in the season, he stands up and makes a nuanced speech about the importance of the family, but even more of the Reich, and the idea that finite human lives find meaning and immortality by being dedicated to the Reich. Is he a hypocrite? A “good” Nazi?

In Philip K. Dick’s original novel, The Man in the High Castle was the author of a forbidden book called The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, which posited an alternate history where the Nazis lost World War II, and the newly-powerful United States divided the world with a resurgent British Empire. The Amazon adaptation has swapped out the book for a series of visually arresting film reels that show countless alternate versions of history. In some the Allies win, in some Stalin has forged alliances with unknown leaders, but in most, San Francisco is flattened by an atomic bomb. In a truly inspired choice, however, High Castle has also emphasized the importance of books in kindling insurrection.

In season one of High Castle, The Bible was the fulcrum book. When Juliana Crain traveled to The Neutral Zone with a copy of the film reel called The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, she ended up in discussion of The Bible that led to bitter reprisals from Nazi agents. Here we see the effects of a few forbidden books in the second episode, “The Road Less Traveled”, and find some of the best moments in the season.

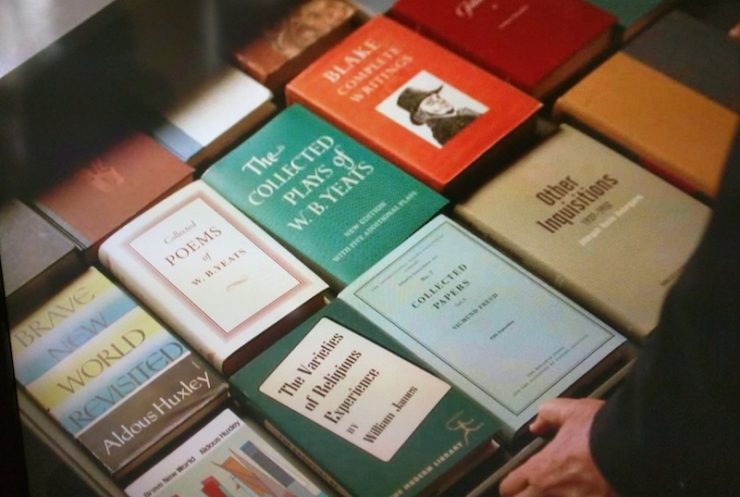

At the end of last season, Trade Minister Tagomi somehow transported himself to an alternate timeline, in which the Allies won World War II. He’s understandably obsessed with the experience, and thinks it may have been a vision. He goes to the Pacific States University Library to see “suppressed volumes”, focusing on William James’ The Varieties of Religious Experience, but doesn’t find any concrete answers. Later, he’s able to return to the other timeline again, but finds that life there is far from perfect. He seeks out “North Beach Books” which is obviously a stand-in for San Francisco’s famous bookshop City Lights. He finds copies of the suppressed volumes out where any free American can purchase them, and for a moment he seems happy. I felt myself relaxing a bit. He’s safe here, right? He’s in our world, more or less, our America, where he’s free to read whatever he chooses. But then, inevitably, he finds a book on that timeline’s World War II, recoils in horror from images of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

A few moments later the episode checks in on Joe Blake. He’s back at his old girlfriend Rita’s place in Brooklyn, reading The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to her son Buddy. Inevitably, reading Huck leads directly into a discussion of moral relativism:

Then I thought a minute, and says to myself, hold on; s’pose you’d a done right and give Jim up, would you felt better than what you do now? No, says I, I’d feel bad—I’d feel just the same way I do now. Well, then, says I, what’s the use you learning to do right when it’s troublesome to do right and ain’t no trouble to do wrong, and the wages is just the same?

Buddy asks about the differences between right and wrong. The boy already equates “right” with work, praising Joe for going back to work to “help build the Reich, one brick at a time.” Joe says that “when people believe in you, you want to prove them right” which is sweet, but little Buddy has another question: “What about Jim? How can he be good—he’s black!” And Rita walks through the room and says “They burned that for a reason, Joe. Buddy doesn’t need to read about those people.”

Joe bites his lip, clearly conflicted. For a moment I thought this scene was a glimmer of hope, as well as a perfect meta-commentary on Joe’s situation. Slavery was legal in 1840s Missouri, but more than that it was accepted by the entire society, and considered to have a divine mandate. Racism was still an acceptable social trait in the 1880s, when Twain published the book. As recently as this year people have fought over whether the book is appropriate for high school-age readers, either because they consider the book too racist or not racist enough. Huckleberry Finn’s plot hinges on the idea that a child is able to experience enough empathy with an enslave person that he breaks through a lie he’s been told since the moment of his birth. If the book works, it tells its readers that they, too, can break through their society’s lies.

But the catch here is that Joe doesn’t see the light, and try to become a better person in our society’s idea of that term: he dedicates himself to finding his long-lost father, a decision that takes him to the heart of the Reich, and far, far away from Mark Twain’s ideals. But in his own mind, is he doing the troublesome thing, the “right” thing, and sacrificing his conscience to honor his father? Or is he doing the easy thing and fully embracing the Nazi ideal?

Where Season One raised many interesting questions about the nature of reality, and the harsh reality of living under a totalitarian state, Season Two gets darker and messier by inverting many of the tropes we’ve come to expect from dystopian stories. Here the noblest, most stirring speech is given by a Nazi. Sadistic bureaucrats risk their own lives to maintain peace for their citizens. Most of the Resistance fighters we meet are driven by revenge, and take glee in the pain they cause. The most progressive citizens on the show are the result of Nazi breeding program, and we’re made to expected to feel sorry for a propaganda minister. More than anything, this season hangs on the idea that empathy can change the world—it’s the thing that creates the tiny cracks in the reality of an inherited society that allow new ideas to get in. It’s Juliana’s empathy for Joe, despite his Nazi past, that causes her to find some good in him, and to later find reasons to like Helen Smith’s family and circle of friends. It’s what allows alternate-universe Tagomi a crack at a different life. Over the course of the series, this trait becomes increasingly vital as tensions rise between the Reich and the Japanese Empire.

But at the same time the show is asking us to think about how much empathy we can be willing to extend. At what point do we stop making allowances because of the culture of the Reich, and the Pacific States? At what point does Juliana become complicit in the Reich’s actions, which she seemingly considers evil? When do we give up on Joe and his eternal uncertainty about his own morals and heritage? When do we demand that people draw a line and stand for what they believe?

The Man in the High Castle’s second season isn’t as taut as its first, but as this difficult year comes to a close, and we face an unknown future, I’ll welcome any art that forces me to ask these questions.