Welcome to Freaky Friday, that day of the week when a beautiful coffin arrives at your front door and you don’t remember ordering anything from Amazon but then you open it anyway and a monster arm comes out and strangles you.

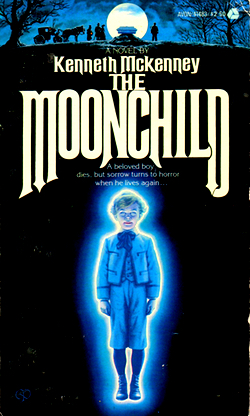

When I was a child, I appeared in a lot of community theater and I was often dressed like that small child on the cover of Kenneth McKenney’s The Moonchild, minus the glowing. Like that small child, I was forced to wear little Lord Fauntleroy suits and stage make-up and, glancing into the mirror backstage, I did not feel like a powerful thespian capable of commanding attention and inspiring awe. I felt like an emasculated gerbil who would be lucky not to get stomped to death by a startled housewife. But McKenney wants us to fear this Moonchild on the cover of his book, and if you stare at it long enough you will fear him. You will fear that maybe one day one of your own children will start dressing like him and then you will have to drive them far off into the country and put them out of the car, and drive away.

But if you can get past that instinctual fear we all have when confronted with a small child wearing lip gloss and knickerbockers, you will find within these covers what is basically a Hammer horror film in prose form. And that’s a good thing because winter is coming and that’s the time for a mug of hot cocoa, a roaring fire, and blubbering but loyal servants, old crones muttering dire warnings, and coach chases through snowy Bavaria landscapes. And also class warfare.

Once upon a time, when he was a young man dressed in lederhosen, Edmund Blackstone came to Bavaria to study the manly art of boxing. Now, rich beyond his wildest dreams thanks to his inheritance from his father, an importer of German wines, he and his good wife, Anna, have returned to celebrate Christmas in these hills he loves, along with their tiny child, seven-year-old Simon. But Simon has taken ill and he lies in his bed in their hotel suite, coughing and saying brave things like “Will I be home for my birthday?” and “I’m feeling much better.” In other words, he’s basically got an expiration date stamped on his forehead.

Their doctor writes to Professor Albricht, a “world authority in fevers” who recommends packing the wee lad in ice water. He dies. On Christmas Day. After buying a tiny coffin, Edmund and Anna are approached by an old crone who mutters that their dead child is a Moonchild. After doing a lot of research, their doctor discovers that a Moonchild is a kid born on a super-leap year who is damned forever because that’s just his bad luck. What does it mean? “Your child is a Moonchild. He is a child of the moon,” explains the doctor. Yes, but… “Don’t ask me questions,” the doctor snaps. “There is no explanation.” So what happens next? Simon must be buried where he was born before his next birthday. Why? “No one seems to know,” their exhausted doctor says.

The Blackstones think this is all ridiculous until the lad’s blubbering nanny volunteers to sit up all night beside the boy’s wee coffin and the next morning they find her with her throat ripped out by a monster claw that’s appeared on the end of dead Simon’s arm. At that point, the Blackstone’s pour themselves a stiff cognac, pack the tiny cadaver into a jeweled Spanish coffin covered with carvings of flowers and rhinestones, and race for England by coach, hoping to get there in the ten days remaining before Simon’s birthday. As for the loyal nanny? They just jam her under the couch and figure they’ll send her parents a note when they get home.

That doesn’t wash with local cop, Sergeant Obelgamma, who suspects them of murder, but since this is basically a Hammer film where every servant is loyal and every local police constable is bumbling, he makes a hash of things and soon Inspector Leopold Fuchs of the Munich Municipal Police is hot on the trail of the Blackstones as they flee across the snowy Bavaria landscape, which is like a Currier and Ives print, only littered with mangled corpses. See, despite having an elaborate secret locking mechanism, Simon’s coffin pops open pretty much anytime anyone even glances at it, and then his powerful wanking arm, swollen to monstrous size, strangles them.

With long descriptions of after dinner brandies and local beers, and every breakfast of cold meats and rye bread described in lascivious detail, The Moonchild is full of silver pots of rich, steaming coffee and freshly baked bread, its crackling brown crust concealing a moist, steaming, soft interior. The Blackstones stay at lovely grand hotels and charming snowbound inns when they’re not stopping off at warm welcoming taverns, and it’s quaint to the nth degree. But it’s also got the other side of the Hammer film down pat.

Hammer films with their mad scientists and aristocratic vampires doing battle with various Barons, professors, archaeologists, and doctors are basically just two members of the upper classes duking it out over who will get to exploit the other 99% of the world, and that class warfare comes to the fore in The Moonchild. After leaving their nursemaid on the floor of their hotel like an old sock, the Blackstones catch a train and wind up tossing the mangled corpse of the conductor out the window with no more thought than one would give to tossing a cigarette butt onto the tracks. A cigarette butt with arms and legs and a family and children.

And yet the lower class do have their uses. Despite Anna and Edmund loving each other “without the demands of passion” after dumping this working class meatbag onto the tracks, Anna turns to her husband and gasps, “Will you come to me?” and then we do a slow fade as they collapse together into her sleeping berth. The Blackstones never even knew the name of the doctor who did so much to assist them in escaping with Simon’s body in the first place (it’s Dr. Kabel, by the way), even after the events of their Moonchild drive him mad. They leave dead train conductors, porters, nursemaids, and coachmen strewn in their wake like gum wrappers, all of them ravaged by their son because they can’t figure out how to keep the lid of his stupid coffin closed. Then, when they finally reach home they discover a vast muddy field where their old house once stood. A deep hole is dug by an obliging night watchmen with a hairlip who appears out of nowhere (“Well, sir, a good watchman expects anything. Anything at all, if you understand my meaning?”) and then it’s revealed—shock! horror!—someone must be buried alive as a “guardian” with young monster Simon.

Fortunately, that’s right when Inspector Fuchs catches up with them and with nary a second of hesitation he recognizes his social betters and leaps into the open grave, begging them to cover him with dirt so he may be of some use to the upper classes. After burying him alive (“He did give the impression of a gentleman who knew his business,” the watchman observes) Anna and Edmund head back to their mansion, grateful that no matter what ills may assail them, there are always those less fortunate who will throw their bodies in the path of danger. And, even better, the entire time he was being buried alive with their child, Inspector Fuchs never forgot to refer to Edmund Blackstone as “sir.”

opens in a new window Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.