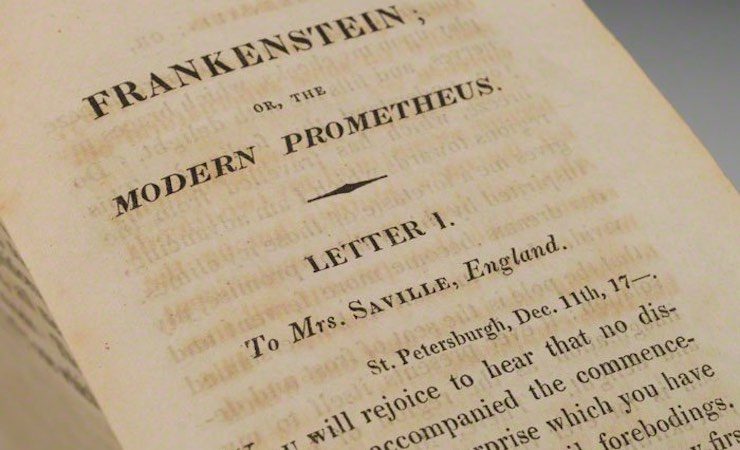

This summer marks the 200th anniversary of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein—and it holds a special place in our hearts as one of the forerunners of modern science fiction. While the book wasn’t published until 1818, the story was first conceived in 1816 during an iconic tale-spinning session she shared with Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, Claire Clairmont, and John Polidori while on a particularly rainy holiday in Geneva.

We wanted to take a moment to celebrate the novel, and we could think of no better way than asking authors Victor LaValle (The Ballad of Black Tom) and Maria Dahvana Headley (Magonia) to talk about Mary Shelley, Victor Frankenstein, and their various creations. Victor and Maria were kind enough to meet with me, Katharine Duckett (of Tor.com Publishing), and Irene Gallo for a lunchtime chat about monsters, motherhood, and Promethean desires, and I’ve done my best to round up the highlights of our conversation below!

First Impressions

Maria: Years ago I read part of The Last Man, but I was never a huge Frankenstein geek. Maybe ten years ago I realized I had never read it, so I went and read it, and of course it’s quite different from the book you think it’s going to be… just so much sadder. So sad. I thought it was going to be a horror novel, and it so isn’t, but it also has the whole expedition element—so many genres in that book. Even if you haven’t read it, you think you know it—the monster is so much part of our pop cultural understanding of human interaction at this point.

Maria: Years ago I read part of The Last Man, but I was never a huge Frankenstein geek. Maybe ten years ago I realized I had never read it, so I went and read it, and of course it’s quite different from the book you think it’s going to be… just so much sadder. So sad. I thought it was going to be a horror novel, and it so isn’t, but it also has the whole expedition element—so many genres in that book. Even if you haven’t read it, you think you know it—the monster is so much part of our pop cultural understanding of human interaction at this point.

Victor: I definitely think it was a revelation for me. I think I must have seen it—maybe I was seven—my uncle said let’s watch Boris Karloff in Frankenstein, and the first time I read it was probably high school? And I thought it was awful because it wasn’t the movie. I had that bias. And to the movie’s credit—it’s a movie. It’s much more streamlined, and it’s much more modern. And only coming back to read the book…actually my wife taught a class called The Narrative of Birth, and this was one of the books she included in that. And she said “you need to read it again so we can talk about it, but also to see now as an adult what you think”. And I remember being similarly shocked by what a different experience it was. And if you’re too young, or not in the right mind frame for something, you can easily dismiss it as just lousy, but if you’re lucky maybe you can come back to it, and think, man, I was so ignorant. There were so many things I just did not understand. And then it blows my mind to think: [Mary Shelley] was 18 [when she wrote Frankenstein]! So, OK, I just had to wait until I was 40 to catch up to that 18-year-old.

On Power and Control

Maria: I’ve just been reading A Monster’s Notes. It’s heavy, and it’s full of many different…the author, Laurie Scheck, is just riffing on all the things that Frankenstein makes her think about, through the lens of Frankenstein’s monster. And one of things that I was reading on the train just now, which makes so much sense and I’d never thought of it, is a bit about Robinson Crusoe. Which I read when I was 10, along with Swiss Family Robinson. It’s the story of this guy who has to start out at the beginning by himself. Sheck’s talking about Robinson Crusoe and Friday in that book, and how he’s like “I’ll take you in as my child, essentially, my child/companion/slave, call me Master.” That is equivalent to Frankenstein and his monster too, and it’s so disturbing. As a child reader it’s such an easy-to-read adventure story that it’s like a distilled version of Frankenstein in some ways. Then you come forward to read Frankenstein, and it really is a birth story in a way—“I made this monster!” rather than “I found someone and made them into my monster!” So it could be a way of getting around the obvious—to a contemporary reader—problems of owning another person. The monster is made. I was thinking abut the temptation of a narrative in which you have power over someone else—especially as a kid—and someone else is yours, and I think that is the temptation of Victor Frankenstein in the pop imagination. This idea that you’ve made a monster, you have power, but then you run into the problem of “what if my monster is bad? What if my monster disobeys?” And then, the book itself is so concerned with adult themes, so concerned with beauty, with what happens if you’re ugly… that’s the major thing that I noticed this time around. Before I thought it was all about birth and creating something, but now I think it’s about the problems of not being beautiful.

Victor: It’s funny, along those lines, the wish fulfillment of it, as a kid, of wanting someone to control. When I was reading the book more recently, I kept feeling skeptical of the stance ascribed to Frankenstein’s monster—that he should slavishly want acceptance into this society, and his father’s acceptance. At the same time, I understood that of course that’s a profound motivation—it felt so real—but part of the reason I felt angered, or frustrated by that, was because I wished it wasn’t true. That it would be such a powerful draw for humans. There’s a poem by Van Jordan, he read a story about a woman who killed her son—the baby was about 2—and the baby is in the afterlife, trying to explain to God why his mother should still get to Heaven. And he’s pitching, “Here’s why. Here’s what was good about my mother.” And the heartbreak of that, as an adult, you’re sitting there reading, like, don’t you understand what your mom did? And the genius of the poem is that the details of the murder are in it—it’s not like he’s hiding it—but the child is saying don’t you understand that this supersedes that? What’s even more powerful than the desire to punish is the desire to save. Or, the desire to love that parent, sometimes the worse that parent is, the more you work to save that parent. I felt like that with Frankenstein’s monster: “You’re eight feet tall! Just crush him, and go on.” But of course it makes sense that he can’t.

Maria: So there’s the desire to please, but it’s not the desire to forgive. That’s a different complexity. The poor monster isn’t graced with that power. All he can have is, “You have to love me. You did this bad thing. I understand what the bad thing was and I can hold it inside myself and still be able to go on.” He has to have his father back.

Victor: Or kill everyone.

Maria: Or kill everything… or be on an ice floe.

Victor: Of those options, that seems like the best one.

Maria: It’s not a bad outcome, ultimately. I prefer ice floe of all the possibilities, as opposed to underneath a house in a little shelter, where he’s not able to stand up, looking into the house through a tiny crack.

On Creation (And MURDER)

Victor: The other thing I marvel at in the novel, is the way Shelley so quickly does away with the—in theory—big plot points. Like, when Frankenstein’s making the Bride? And then he just kind of breaks her into pieces and sinks her in a lake. That’s it! That was a whole second movie! I’m so impressed with her, “I have so much in here, that this thing? [snaps fingers] Done. Move on.” It seems very confident as a writer. Same thing with the creation of the monster. “You don’t need to know. There was bad stuff… and then it blinked, and it was alive.” As a reader I think that’s the only way you could do that scene. Otherwise people would think it was silly.

Maria: And at that point you’re not going to describe childbirth, you’re not going to describe infant mortality on the page.

Victor: That’s right.

Maria: Which is what both of those things are… the killing of the bride, it’s such a strange, like, two sentence thing. “I quickly moved my hands in a certain way, and she was dead!”

Victor: And then I sank her in the lake.

Maria: Yeah! And it’s a little bit messy, clearly…. I was thinking about one of the key sins of the monster, which is that he refuses to kill himself. There were so many suicides all around Mary Shelley. It’s interesting that one of the things that makes the monster problematic is that he won’t take responsibility for his own death. Just like anyone, he’s not responsible for his birth, but…

Victor: Is Frankenstein often trying to get the monster to kill himself?

Maria: I think he’s wishing that he would.

Victor: He’s just wishing it was away….

Sympathy For The Monster

Victor: I have the Norton edition with critical essays, and one of them is about all the editing that Percy Shelley does to the book, and that his sympathies apparently, are entirely with Victor Frankenstein, while Mary’s are, not entirely, but much more with the monster. And I was just amazed, because from the pop culture existence of the monster, to the movies, it’s like: “How could you be that wrong about who humanity is going to side with?” Maybe that was almost the point? Who got to last? Percy just thought that Victor was the one you’d be brokenhearted for, and it’s just… how?

Leah: Well, he’s the human striving for something, right? For Shelley, especially, usurping Nature…

Maria: And the quest for intellect… although, reading it now, I feel like Victor Frankenstein is a bro. He’s so privileged, so protected. “I can do what I want! Everyone loves me, and a bride has been brought to me from her early childhood. I have always had a bride. And later, I kill her! I kill all the brides.” He’s a really privileged serial killer in a certain way.

Victor: Thus, Shelley.

[laughter]

Victor: I could see why his sympathies might lie… if you watch a movie that in theory has a diverse cast? And then you ask people, “Who did you like? Oh, the person who looked like you? Ah, right.” It’s a human failing. Or, just a reality of humans. So it would make sense that Shelley’s sympathies would fall there. I always like to dream that someone’s intelligence would save them from such things but it almost never does. So I always remember, you know, “keep that in mind, if you start getting too full of yourself…”

Maria: Your intelligence can’t save you!

Victor: You’ll end up on an ice floe.

[Katharine asks them to elaborate on an edit to the ending of the book.]

Victor: At the end of the official-ish version, the narrator—the creature jumps out onto the ice floe the ice flow is taken by the current, and is lost in the dark. That’s [Percy] Shelley’s ending. Mary’s ending was that the creature jumps out, and he pushes off from the boat, so that he’s refusing society. The narrator, Walton, who has said many times earlier, “I’m just like Victor Frankenstein” he loses sight of the creature in the dark—it’s not that the creature is lost, it’s that his powers fail. Here was more—or at least you could read into it—much more about a willful choosing to refuse society that the creature was born into, and that the avatar of that society was not an infallible being. His sight could not see all, and the creature lived beyond him, and that was in some ways for Shelley, Shelley could not abide that that Walton would not be able to, in all ways, fathom the universe. But maybe Mary Shelley wanted to leave room for the idea that he’s not dead. I don’t see why “lost in the dark” means he dies, but a lot of people apparently read that as his death. Percy wanted more of an end, where Mary was more… “maybe a sequel?”

[laughter]

Katharine: The creature does seem pretty resilient.

Maria: Impervious to cold, impervious to, well, everything…

Victor: And a vegan! He’s going to live a long time.

Maria: It was interesting reading it this time, I thought the detail that Victor Frankenstein’s hands aren’t dexterous enough to make a monster that is human-sized, he has to make the monster big, because he’s not a good enough sculptor, so it’s completely his fault that the monster is eight feet tall…he doesn’t get enough training, essentially to be able to work with the small important parts of the human.

Victor: I didn’t remember that detail at all…so that’s an admission of fallibility as well, then? So that made it in.

Maria: Victor is the reason the monster is ugly, and he knows it. He just doesn’t realize it until the monster opens his eyes, and then he’s like, “Oh! Ugly! Whoops!” and just runs.

Katharine: I really failed!

Maria: Yeah! Then there’s the revelation of: MONSTER.

On Death

Victor: I can’t remember, or is this like the movie, he’s not cadaverous, right? He has long hair? Is that right?

Maria: He’s made of parts, different body parts, because Victor Frankenstein is working in the medical world, he has access.

Leah: But there isn’t the—in the movie they always make a big deal of the grave-robbing scenes.

Victor: There are no scenes, he just takes it from the medical school.

Leah: And no one questions it?

Victor: Which again goes back to impunity. Absolute privilege and power: “Yeah, I’m just gonna take some parts, no big deal!”

Maria: Did you read the amazing pieces about New York’s Potter’s Fields? [Ed note: You can read those articles here, here, and here.] They were in the Times a couple months ago? It was about this. The way that the mortuary and medical industries are just allowed to have bodies, and bodies are lost… just lost. And ultimately the families of the people who ended up in these fields had no idea they were there. They’re on this island, [Hart Island] this very mixed group of people, who were basically forgotten about, or unclaimed because no one told their families, for 24 hours, and then the city takes them.

Victor: The families of people who donated their bodies to science—it seems okay, right, if their loved ones were used in that capacity, but in the end, the body was still just gonna be some meat left somewhere. But it clearly hits so differently to think, “They just got dumped?”

Maria: In a mass grave.

Victor: In a mass grave. It just feels so much worse. Even though they would have been dissected, and… roughhoused worse, through science, but it would have felt better. There would have been choice in that, I guess.

Maria: There’s still that question about, what are you allowed to do with the dead? And in so many ways. There’s this recent… a study using stem cells to stimulate the legally brain dead.

Victor: Oh, wow.

Leah. …huh.

Maria: Which is pretty intense. With the goal of resurrection. It’s just in the last couple of months. And that’s what Frankenstein is about. So…what does that mean? Does that mean that if it works we’ll have a resurrected Frankenstein’s monster class of people? Does it… certainly there’s a taboo, and there are so many scientific taboos about what “dead” is. An ongoing discussion about whether you can unplug someone. This study is happening in India, and involves both American and Indian scientists. They have 20 subjects and they’re all legally brain dead, and this would be stimulating their reflexes, but also stimulating their brains. Are they going to be…

Victor: The people they were?

Maria: Yeah!

Katharine: And they can’t give consent, obviously.

Maria: Yeah! They’re test subjects, but they can’t give consent. [Edit from Maria: I wish I had managed to get to talking about use of immortalized cells—for example, famously, the cells of Henrietta Lacks, used without her permission or knowledge to culture the first immortal cell line, the HeLa line. So relevant to Frankenstein.]

Victor: Even people who are really against it will be like, “…ah, but tell me how it goes?” Of course, as soon as you start talking about that my pop culture junk mind goes back to that ‘90s movie with Kiefer Sutherland…

Leah: Flatliners!

Victor: Yeah! But it also, I can’t think of very many human cultures where returning from the dead is cast as, “And then everything went fine.” I really can’t think of very many. Lazarus, I guess? In theory? But you never hear anything, he just went on.

Leah: But if you go with Kazantzakis, with The Last Temptation of Christ, then he just gets murdered later. He only lives for like another month.

Victor: And the whole thing was just to prove that Jesus was the Son of God.

Leah: Yeah, because Lazarus seems very unhappy about the whole situation.

Maria: So then you run into the taboo of… It’s like waking from a really bad dream? Are you allowed to wake up? Does it make you a monster if you wake up from a bad dream that is actually death, not a dream? That’s what happens to Frankenstein’s monster, I think. So is it the taboo of the collective souls? He’s many different bodies, is he many different souls? Does he have a soul at all? Because the problem really begins when he opens his eyes. All he does is open his eyes and then Frankenstein runs from him.

Leah: We don’t get any sense of if he has memories from before. Presumably there’s a brain in there…

Victor: He has to learn everything over. Language…it seems as though it’s been washed. It’s a hard thing to imagine. Or even more perverse is the idea of coming back because then as human I would think, well, if your brain is that intact, like a black box recorder, say, then what did your brain bring back from wherever it was? Or wherever your soul was? The question begins to become—if you’re still you, then where were you?

Maria: This is a sideways conversation, but I had a near-death experience when I was a teenager, I left my body, went up to the white light… I don’t believe in God, I have never believed in God, and still don’t. But it was… very convincing. I had a choice of whether to return or not, and somehow that choice was mine to have. I looked at my body from above, and it was like, “Well, what do you want to do? Do you want to go back, or not?”

Victor: Was that a feeling, or was it actually a feeling of communication?

Maria: It was a feeling of being spoken to. But, the casualness of it—that’s what’s more relevant to Frankenstein—it was a thin line between being alive and being dead. It was very similar. So when I got back I spent the next year recovering, because my body was messed up, but also, feeling like I was dead for the whole next year. I was in 9th grade when this happened, and I became…there was no part of me that was part of human society. I couldn’t fit in at all, because I felt like I’d been dead. And it’s… it’s why I do what I do for a living now, it made me into someone who’s like, “Monsters! Monsters everywhere, they’re right here.” Because it was a monstrous feeling. Like, I know that this isn’t such a big deal now, and everyone else is like, being alive or being dead is a big deal, but I had this feeling that none of this [indicates restaurant, and life in general] was a big deal. It was a bad feeling to have at that point, as a teenager, full of hormones,

Victor: Where everything seems big and important.

Maria: I had very, um, ice floe desires at that point in my history! But the fact that the monster has to start from scratch with morality. That’s a huge part of adolescence—you think you have your morality figured out, you’ve been raised with your family’s beliefs, but then suddenly you’re a teenager!

[laughter]

Maria: And it’s like, reboot: I am now controlled by a force I don’t recognize. All of which—Mary Shelley’s writing this at age 18, and she’s pregnant, I think?

Victor: Yeah, she’d had the kid. She had a child several months premature, she gave birth, but then the child died soon before Frankenstein was published. Actually in the piece I read, it was very sad—she kept an extensive journal, and the day she finds the baby, the entry is just, “Found the baby dead. Very sad day.”

Maria, Leah, and Katharine: Oh.

[Between us, we try to work out the timeline of births and deaths.]

Maria: And then she keeps Shelley’s heart.

Victor: She kept his heart? I didn’t know that one.

Maria: His heart didn’t burn. She’s not there for the burning of the bodies (women were not allowed at cremations), but the friend who was there brought her Shelley’s heart, which she kept for the rest of her life. [Edit: Current theories suggest that the heart was calcified due to an earlier bout with tuberculosis. She apparently kept it in a silken shroud wrapped in one of his poems, and a year after her death, it was found in her desk.]

Victor: That’s too on-the-nose for fiction, but perfect for life.

On Perspectives and Editions

Maria: So …I guess I didn’t realize that there were two editions. There’s the 1818 edition, and the 1831 edition. And apparently they’re pretty different.

Victor: It’s in the Norton edition, there’s an essay about the distinctions between the two. I don’t remember which is supposed to be the definitive.

Leah: I think the ’31—the ’31 is the one that I read. She softened a lot of it, made it a little more mainstream. A lot more about nature, descriptions of Switzerland, a bit more moralistic, where before… Victor isn’t valorized, but we go a lot more into his mind, his obsession.

Victor: The one I have is the 1818, it is… Victor goes into a lot. It’s funny, in the essay about the comparisons between the two, seeing where Mary will use one word, Percy will use nine words. A lot of the natural world stuff I think is him. Like, she had it, but he was like, “No, rhapsodies.”

Leah: Yeah, that was what got to me when I was rereading it! We’ve got an action scene, and now we’re going to have a description of a mountain, for five pages. It’s very Romantic—capital-R Romantic—but it doesn’t really fit with this tense story. Kind of an interesting way to weave in the Romantic parts…

Victor: You get to see the marriage on the page.

On Companionship

Maria: The narrator [Robert Walton, who narrates the book through letters to his sister], his main complaint is that he wants a companion, but not just a companion, he wants someone smarter than he is. And you have to wonder if that’s something [Mary Shelley] was looking for? Is that something she had to have? She “had” to have Percy to teach her how the world is, even though she clearly has a lot of ideas about how the world is, a lot of pretty transgressive ideas about the world, but there’s such a theme throughout this book, of, you must have a companion. You can’t go it alone. For a woman in this moment, it makes sense structurally that it might feel that way. In this book, it’s very much about a man’s companionship with another man, and when Victor starts to talk about the monster escaping—well now the monster is his companion, and he is so fucked, because that monster is going to be a very problematic companion. But that’s who he’s got now. And the monster is going alone into the northernmost unknown. That’s part of his monsterhood. He’s going into the dark, without giving a fuck. He didn’t come from the dark, he came from this brightly-lit medical scenario – he didn’t come out of a womb. He’s doing something humans don’t do. He is going into the place where all the other beasts are.

Victor: At the end he’s going into a womb. Giving birth to himself.

Maria: A stormy womb. But that’s a topic—Mary Shelley clearly had a stormy womb.

Victor: I also wondered—it does seem like in the stories of all this it’s Byron and Shelley, Byron and Shelly, Byron and Shelley. I wondered if she’s also making fun of them a little bit. He [Walton] is so desirous of that male companion, and when Frankenstein shows up he’s overjoyed, but it’s preposterous. He seems pathetic, because he’s out there, telling his sister “I have to stay out here until I do something great!”—but he seems like kind of a nothing, or, at least as far as adventurers go a bit of a dud, and then this guy comes along, and any sane person would think, “This is really problematic” [laughter] …but Walton is so needy, he’s like, “Tell me everything! I love you!” And I wonder if that’s Mary, saying, “That’s you two idiots.” That she’s skewering that bro-ish thing of, “I choose my guys. I always choose my guys” because the women just keep getting killed off. The one that bothered me the most is Justine—Victor knows she didn’t kill his brother, and he just doesn’t say anything, because he doesn’t want to embarrass himself. This is who you are. You would let a woman die rather than be shown to be less of a great mind than you want to be. I wonder if that current was in there, as well.

Maria: The idea of collaboration is always seen as a “good thing.” As opposed to the possibility that it could be a totally destructive relationship, you could end up collaborating badly. And Walton is only taught Victor’s story—which is a story with significant excisions, with Victor as the victim. How is he a victim? It’s such an example of that Great White Narrative: “I am a victim of all the “savages” of the world! Nothing I did caused this to happen!”

Victor: “I meant well, so how could any of this be my fault?”

Relatable Monsters

Maria: I think the (weird, but typical) idea of creating a relatable protagonist—or monster—is that you ferociously narrow your focus toward readers into a number you can count, I think we all take this into our bodies, and wonder, how will I make something that people will read? How do I tell a story that is relatable to a group that I can understand? I think sometimes that’s poisonous to storytelling, you end up un-monsterizing your work. Trying to make sure there’s no, ah… [Maria turns her hands into claws and growls] you know, something that’s jumping out of the dark, or into the dark! But that’s what’s interesting about reading. The way we talk about Frankenstein, the way we talk about what the story is about: Is it a story about the quest for knowledge? Is it a story about enslaving someone who is newborn, an innocent? A story of someone who’s like, I made you, and now I can do whatever I want to you? That’s a scary story to tell, if you’re telling it in the positive as Victor Frankenstein is telling it.

Victor: It’s so brilliant reading about Boris Karloff and James Whale’s choice to make him inarticulate, and Karloff particularly said, “He’s a three-year-old” and that’s how I’m going to play him.” And rereading the book, realizing that for all the way he’s articulate, he is a three-year-old. Forgiveness is not a part of his make up. Forgiveness strikes me as something you mature into. That was the relatable other way to come into that story, that keeps the creature monstrous, but stopped privileging Victor Frankenstein.

Victor and His Creature: A Love Story

Maria: It’s interesting to think of this story as a love story. The creature is an intellectual lover that he’s created for himself, he’s made himself a better bride, because his poor own bride is deprived of intellect, she doesn’t ever get to be smart, she’s just lovely, so he creates the monster, and it’s a bad love affair.

Victor: Because Victor can only truly love himself.

Maria: So, abusive relationship! The monster’s like, I’ll kill all your other lovers, maybe that will fix the problem.

Victor: And still, no.

Leah: Yeah, the monster finally gets there, and the ship captain has already latched onto Victor. Even there. “I was only gone on the ice floe for a little while, and you already found somebody new!”

Maria: Victor’s a player!

Victor: It’s taken for granted that he’s charming and charismatic.

Maria: It’s interesting too, because Victor Frankenstein destroys himself. He’s golden, he’s golden, but then he basically dies of confusion. He keeps having attacks of confusion because the world isn’t happening according to his narrative, his monster is ugly…

Victor: That was not the plan.

Maria: And then he collapses.

Leah: On the ship, with his poor, doting would-be BFF.

Maria: His would-be bride. And the monster breaks all the rules of polite society. And his heart is breaking with longing. And that isn’t something that fits into Victor’s narrative.

We ended on the consensus that Frankenstein is even weirder than we all remembered, and more of a tragic love/slavery story than a horror. (Though there is plenty of horror in that narrative.) What do you think, Franken-fans? Are these points the birth of a new Prometheus, or are we floating out to sea on an ice floe of conjecture? I ask because as the very end of the conversation, Maria gave us a path forward: “I was just thinking, I need to read Journey to the Center of the Earth, I’ve never read it before….”

[tantalizing pause.]

So perhaps the Victor and Maria Lunchtime Classic Sci-Fi Hour will return with Journey to the Center of the Earth!