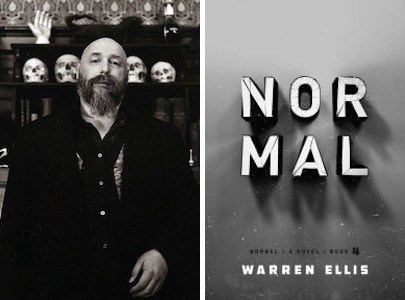

Our friends at FSG Originals are publishing Warren Ellis’s new novel Normal in four weekly digital installments. The fourth and final installment was released this past Tuesday and is available wherever e-books are sold. Each week, Tor.com has hosted a discussion between Warren and a new writer about that week’s episode. This week, to close things out, it’s Lauren Beukes, author most recently of Broken Monsters and The Shining Girls along with the about-to-be-reissued Zoo City and Moxyland.

Normal is the new serialized digital novella from Warren Ellis, the guy who packs more ideas into every page (or every panel in his comics work) than many writers would use in a whole book.

His publisher FSG Originals asked me to ask Warren some questions about the fourth and final installment, which will be out in actual book form later this year. And it’s great. Normal is hectic and smart and brutal and funny, and queasy-making, too. Like William Gibson and Margaret Atwood, Warren is one of those writers who seems to have an all-access backstage pass to the total weirdness of the now.

In the Oregon woods is an isolated and disconnected convalescence facility called Normal Head that caters to professional futurists and spooks suffering from “abyss gaze.” But when a man disappears from his room, new inmate Adam Dearden has to try to unite the factions in order to solve the mystery and deal with his own burnout event.

Lauren Beukes: Mansfield’s disappearance and the bed of bugs in his wake had a very Bram Stoker’s Dracula feel—his name evokes Renfield, and he’s also in an asylum thanks to his dark master. Is this me wildly free associating or an intentional nod to the attention-vampire nature of our tech and those info-sucking surveillance lords?

Warren Ellis: Asylum. Bugs. Renfield. I suspect we both have very similar brain damage. I don’t know that I made the specific association while I was writing it, but it was obvious on rereading. That part of the draft was written pretty quickly, and I have a theory that pulp writers working full-pelt just spill out theirs ids and deep memories into the work without even noticing. I’m pretty sure I was in that zone when I pulled a name out of the air for that character and then put bugs in an asylum. The only consciously intentional part was Clough’s terrible joke at the chapter break, probably . . .

LB: I worry about your id, or rather what your id is osmosing from the riptides of the global subconscious. It strikes me that it’s not only futurists, but anyone who tries to parse the strangeness of the world we live in through any art or storytelling is probably more susceptible to abyss gaze. Is it something you’ve experienced?

WE: Okay. You want to know the terrible, awful truth?

I feel great.

Things are awful. Everything is terrible. And the worse it gets, the more energy I feel. It’s like some generator that only feeds on horror. I mean, I’m terrified for my kid, and for my own old age, but goddamn I love getting up in the morning (well, afternoon) and seeing what new shapes the world has twisted itself into. Everything is on fire and I love it. I dole out advice on how to deal with these ice storms of shit that we’re living through and counsel people on how to protect their brains from it all and console people and tell them that we’re all going to find ways to get through it and I am seriously just sitting there with my feet up and an espresso in my hand and feeling fine as the planet eats itself. I’m a monster.

Don’t tell anyone.

LB: Your books are always techno-creepy, but this is the creepy-crawliest, from the heaving mass of insects on the disappeared man’s bed, a shout-out to everyone’s bestest mind-control fungus, cordyceps, and my favorite character, Bulat, even shares an intelligence and a pronoun with the bug-mind of her gut biome. What’s up with all the bugs, Ellis?

WE: Well, first, obviously, it’s the gag. Bugs and bugging. Because I am history’s greatest monster. It’s also our relationship to the natural world. Sit and think about it long enough, and we find ways to be revolted by things we evolved alongside. From one angle, that’s kind of weird. But it’s also a shadow biology—we are now barely understanding gut biomes, the strange mentational pressures of toxoplasmosis, the possibilities of insect consciousness and even insect culture.

It’s that inner-space thing, maybe— not necessarily on the level of Ballard’s psychological definition of the term, but more literal, the “minds” inside us and crawling at our feet, exerting their weird controls and pressures. Even just knowing their presence without quite comprehending them. Just as we can’t, in surveillance terms, ever quite see all the things that are seeing us.

(Wasps injecting venom into ant brains to turn them into zombies!)

LB: As much as your work is concerned with the infinite weirdness of our present, and pinging the future, there’s a lot of history and hauntedness, too—ghosts as well as spooks, electronic and otherwise . . . and forests. How are the psychogeographies of nature different to write about than the typical techno-thriller staging ground of cities?

WE: I dunno. I’m probably kind of perverse about this. I mean, you read Gun Machine—the first thing I did was look for the ancient trackways under the city. I’ve seen Manhattanhenge. While, obviously, footpaths and stone circles are human interventions, they’re also intended to work with, rather than against, natural landscapes. The micro-homes in Normal are intended to blend into the landscape to some extent. I tend to see what’s under things, and to see things as extensions of or emulations of nature. God, I wrote a science-fiction graphic novel about vast alien structures landing on Earth and called it Trees, for God’s sake. There’s something wrong with me.

LB: Is privacy really, absolutely, do-not-revive, no-zombie-resurrection, 100 percent dead? How does that make you feel, and as the parent of a young woman in particular? (Speaking to my own interests, with a seven-year-old growing into a future that’s going to be weirder than any we could have imagined.)

WE: Her generation is actually incredibly good at privacy. They saw the TMI Generation and the Web 1.0 Generation and said Fuck That. It’s why so many of them went to Snapchat, while Facebook started to gray and Twitter hit a plateau, and why they were in IM systems rather than e-mail. They’re the generation that deletes their texts and doesn’t leave trails. They give me hope that we can adapt to this environment, too, and have our own workarounds and protocols.

I don’t think privacy is dead. I think we’ve lost personal freedoms that we didn’t necessarily have words for—like the right to not have your personal information spread across a global communications network if you have a bad breakup with somebody, or if you express an opinion about the social politics of video games, or if you have the temerity to be female-identified. As a parent of a young woman, my first concern is that her voice not be essentially criminalized because it is female.

LB: You’re pretty generous with your source code, sharing curiosities and music and book recommendations and other interesting things you’ve found through your newsletter. It feels like a sneak peek into your own gut biome of influences. Do you keep anything back? And do you have an algorithm for that?

WE: I have a private newsletter that goes out to friends, comrades, and fellow-travelers that contains the stuff that doesn’t go out to the public internet. And I still use local bookmarks for stuff that’s just for me, so, yeah, I keep some stuff back. But, ultimately, all things good should flow into the boulevard. And in these days of loud, churning, and complex Internet spaces, curation still has its value. It’s harder, every day, to see and find the good stuff—so, when I do find it, I like to elevate its profile as best I can. Which isn’t much, but artists and writers depend on that kind of thing, and I learned as a kid that when you have any kind of platform, that that is what you should use it for.

LB: And hey, listen, you mentioned in a previous interview in this series that you were hoping to buy a bunker for your daughter and her friends. Is there any room in there? Are you taking applications?

WE: Depends. What can you offer? I’m going to need a lot of alcohol. Also probably new internal organs. I’m open to negotiation here.

And that’s that! We hope you’ve enjoyed our serialized discussion of the serialized publication of Normal. To quickly recap, you can read Warren’s conversation with Robin Sloan here, with Laurie Penny here, and with Geoff Manaugh here. And you can find Part One of Normal here, Part Two here, Part Three here, and Part Four here. And look out for the paperback bind-up edition in November from FSG Originals. Until then, you can always find appropriately uplifting Normal conversation and jovial camaraderie on Twitter using the hashtag #abyssgaze.