Welcome to Freaky Fridays, where we read books from the past in an attempt to understand man’s ancient enemy: the skeleton.

Skeletons are the worst. They lurk inside our skin, waiting to jump out and use our computers, dance obscenely in graveyards, and conduct unauthorized medical procedures on our young. But even worse than a skeleton is a skeleton doctor. First off, I’m not even sure their licenses to practice medicine are legit. Second off, I think every parent’s nightmare is that your kid goes away to college then calls to say he’s gotten married to a doctor, but when he brings his fiance home for Hanukah she’s a skeleton doctor.

“Your father and I wanted you to marry a real doctor!”

“Mom! A Gina is a real doctor, she just also happens to be a skeleton!”

“You’re killing your father!”

And another mother’s heart is broken.

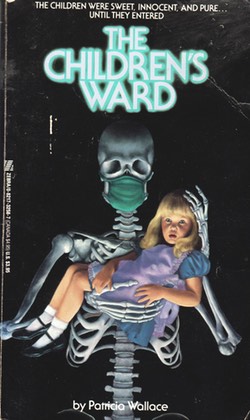

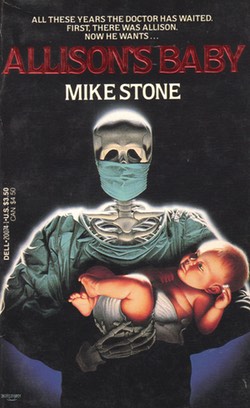

Freaky Fridays has always prided itself on not blindly discriminating against anyone based on the quantity of their skin, so it was educational to read The Children’s Ward by Patricia Wallace and Allison’s Baby by Mike Stone and realize that, yes, in fact all skeleton doctors are fabulously incompetent and should immediately be turned into xylophones.

Patricia Wallace’s prose in The Children’s Ward is swamped with subordinate clauses, making her the Henry James of mass market paperback horror fiction. But rather than exploring issues of personal perception as Americans encounter Europeans, Wallace gives us a book about a cursed, isolated California hospital ward that’s being used to house an experimental treatment program for four children. There’s cold Abigail, wheelchair-bound optimist, Russell, poor little rich girl, Courtney, and Terri, whose divorced parents are engaged in a terrible custody battle as her WASP mother tries to wrest her from the grasp of her father who is half-Native American (or, as her mother calls him, “Half savage”).

On the isolated ward they are observed 24/7 by the head of the program, Dr. Quinn (Medicine Woman), who learns that all of their ailments, from brain tumors to paralysis, are psychosomatic and they don’t actually need surgery or chemotherapy, they just need more hugs. But hugs are in short supply as a physical therapist’s arm is yanked out of its socket and she’s drowned in her hydrotherapy bath, a custodian gets bisected by a power tool, a bad daddy shoots himself, and a ghost beats a mean mommy to death. It turns out that antisocial Abigail is a top psychic and Ward D where they’re located used to be the psychiatric ward before one of the patients went crazy, poked out another patient’s eyes, then ate a nurse. Somehow, the dark forces that lurk in Ward D are amplifying Abigail’s powers and allowing her to lash out at the bad parents of her fellow pediatric patients. We’re never told exactly what dark forces inhabit Ward D but whenever they manifest there’s the sound of wind chimes, so I imagine they’re the spirits of long-dead Zen surfers from Santa Monica.

Meanwhile, Allison’s Baby is, oddly enough, about Allison’s doctor, Jason Fielding, although I suppose a book called Allison’s Doctor might not have been as marketable in post-Omen America. Jason Fielding is a doctor in upstate New York doing research on memory, meaning that mostly he takes hobos and the unloved elderly and cuts out parts of their brains to see if they remember anything afterwards. Most of them don’t, and he locks them up in a rapidly overflowing mental asylum. Why is Dr. Fielding conducting this stupid experiment? Because when he discovers what makes memory “work” he’s going to win the Nobel prize, and if he wins “A Nobel Prize in medicine, the highest reward of his profession, he was certain [it] would finally prove to his father that he wasn’t a failure.” I don’t know. Maybe he’s trying too hard.

Meanwhile, Allison’s Baby is, oddly enough, about Allison’s doctor, Jason Fielding, although I suppose a book called Allison’s Doctor might not have been as marketable in post-Omen America. Jason Fielding is a doctor in upstate New York doing research on memory, meaning that mostly he takes hobos and the unloved elderly and cuts out parts of their brains to see if they remember anything afterwards. Most of them don’t, and he locks them up in a rapidly overflowing mental asylum. Why is Dr. Fielding conducting this stupid experiment? Because when he discovers what makes memory “work” he’s going to win the Nobel prize, and if he wins “A Nobel Prize in medicine, the highest reward of his profession, he was certain [it] would finally prove to his father that he wasn’t a failure.” I don’t know. Maybe he’s trying too hard.

Dr. Fielding’s interest in memory started a long, long time ago when Allison was 14 and she was living in Mountain Oaks, her Catskills hometown, with her reclusive aunt after her parents died. Her mentally ill cousin (who is normally kept chained in an upstairs room) rapes her and gets her pregnant. Because her aunt is Catholic (!) Allison has to have the baby, and then Dr. Fielding raises the mentally ill baby as his own. In a stroke of genius, he uses hypnosis to make Allison forget everything, even her baby. It’s a perfect plan with just one weakness: janitors. When adult Allison (now married to a useless lump named Kenny) is raped by the janitor at the local library she begins to remember what really happened all those years ago. After moving back to her now-dead aunt’s home, she and her memory are all that stands between Dr. Fielding and his Nobel Prize, and it’s going to take a horrible car accident, cannibalism, and secret surgery to sort everything out.

In both books, everyone is terrible at their jobs. Doctors hate their patients and don’t know how to administer CPR properly. Lab techs hate children so much that they stab their arms painfully when drawing blood. Russell fell off a roof, but he wasn’t actually paralyzed until a nurse in the emergency room (a male nurse, I might add) yanked off his pants so hard he shattered the poor kid’s spine. They’re so unobservant that personal injury lawyers can argue with them in their offices one day, then put on a fake beard and mustache and waltz right by them the next. And these terrible skeleton doctors set the tone for everyone else: lawyers sleep with their clients and then trick them, cleaning ladies don’t clean but instead pull their hair out and scream about ancient curses, and parents visit their hospitalized children for less than five minutes before ditching them to attend swank parties.

What makes skeleton doctors, like Dr. Quinn (Medicine Woman) and Dr. Fielding, such poor medical practitioners? And what are the danger signs patients should look out for? Well, if a doctor refers to his patients as “poor unlucky bastards”, be careful. A rampant ego is the first sign of trouble, as in Allison’s Baby when Dr. Fielding’s colleague thinks, “It was demeaning for a neurosurgeon such as himself to be reduced to picking up derelicts, prostitutes, and alcoholics.” You know, for science. Also, doctors who turn abandoned mental institutions or isolated wards that were once the scene of horrible crimes into their own private medical clinics are probably nothing but trouble. Especially when the entrance to said clinic is “an underground passageway behind the morgue.” As one bold nurse says in The Children’s Ward, “They should have known not to put those people out there…so far from the main building. Being isolated like that can’t be good for a weak mind.”

But most importantly, avoid any skeleton doctors conducting studies on bold new medical techniques, especially if their non-skeleton colleagues might call these techniques too bold. You’d think we’d have learned by now, but every time anyone tries to advance the boundaries of medicine they wind up getting in trouble, whether it’s developing anti-Vietnamese piranha, big-brained sharks, plants that can bloom in the desert, or super-fertile chickens. If the people giving out funding simply said “no” each time a skeleton doctor wanted to research anything, the world would be a safer place because time and again, whenever someone does science, it’s innocent people who wind up getting harmed. If people took lessons from the horror genre, medical science should have been frozen back around the time we were burning witches and using leeches. Although then some Einstein would probably make a super-leech and that would go wrong so let’s just say no medicine ever again, just to be safe.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, just came out this past Tuesday. It’s basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.