This essay collects and updates three previously published pieces, along with a new essay on the recently released final novel in The Raven Cycle and thoughts on the completed series as a whole.

Having recently finished reading Maggie Stiefvater’s The Raven Boys for the second time in the course of a month—and if we’re being honest, I think it was less than a month—I feel like it’s high time for me to write about the experience. Because I loved it. I mean, I loved it. I went in suspicious, because the flap copy is truly inadequate to the books these actually are, but within a handful of chapters The Raven Boys had knocked the bottom out of that casual disinterest. As I’ve been saying to everyone whose hands I’ve been able to press these books into for the past few weeks, with a kind of mad joy, “I’m in it now.” There’s a weirdly intense place in my heart that is currently occupied by the complex web of love and devotion and loss that the young folks herein are wrapped up with.

Stiefvater is well-versed in the tropes of young adult fiction and has written a tour de force that illuminates, with careful prose and more careful structure, a set of very real, very damaged, very hopeful characters whose relationships, selves, and world are—fine, they’re utterly fantastic. To give a super-brief summation of the reason I am so attached: these five protagonists are all messily in love with each other, and there’s nothing better or more beautiful or sharp, and it’s going to end. From the first, it’s impossible to avoid the knowledge that all of this wonder is finite. It aches to experience. Plus, it’s a meticulously crafted cycle that rewards rereading in heaps; I’m a sucker for that sort of thing. And that’s not to mention the queerness, the attention to women, and the development of familial attachments alongside romantic and platonic ones, and the treatment of these young characters as real, whole, intense human beings. The depth and care and detail in their development is absolutely stunning.

But enough gushing; let’s talk books.

I: Safe as Life: Complex, Messy Love in The Raven Boys

The Raven Boys is the first of the novels that make up the quartet of The Raven Cycle, with the final book recently released in April of this year. It is, as I described the arc to a fresh-faced friend who had no idea what I was getting her into, the “getting to know each other” book (at least on first-run). Everyone meets; quests are begun; fate starts grinding its cogs on toward the inevitable resolution. The second time through, it was still about first meetings, but also somehow about always-having-met. Stiefvater’s descriptions, the solid and almost-jewel-perfect backbone of the Cycle in terms of character and world alike, are easy to slip past on first read in some sense. They work, and they work well to give you a sense of who these people are.

But the second time, with all the knowledge built in, the smallest of moments and words are layered with a deeper set of meanings. I think on first go-round I was still suspicious of the whole “stay away from boys, because they were trouble … stay away from Aglionby boys, because they were bastards” thing at the beginning, and the “fated love” trope, and all of that. I wasn’t quite taking it seriously, just yet.

But the second time, with all the knowledge built in, the smallest of moments and words are layered with a deeper set of meanings. I think on first go-round I was still suspicious of the whole “stay away from boys, because they were trouble … stay away from Aglionby boys, because they were bastards” thing at the beginning, and the “fated love” trope, and all of that. I wasn’t quite taking it seriously, just yet.

Needless to say, that was wrong, and on re-reading I thought my heart would burst with seeing the boys together and apart for the first time, and seeing Blue for the first time: her commitment to being sensible even though she’s about to fall in with a set of very un-sensible things. “Safe as life,” as Gansey is fond of saying. There are asides and clipped bits of dialogue; each relationship between each pair and set and group of these characters is individual and thoroughly realized. I don’t see development like this in the vast majority of books I read, and I appreciate that it builds even more with repetition.

Really, there’s too much to talk about and be relatively brief, because honest to god I could sit around to pick apart and comment on these books for hours, but I’d like to pay attention to some of the things that are specific to The Raven Boys and strike me as unique. Things that make this a book worth beginning, for new readers, folks for whom “trust me, it all builds up so well” isn’t quite enough of a promise.

On some level, I understand that the reaction I have is both critical and personal. Personal because of the realism of Stiefvater’s illustration of what it’s like to be a girl-shaped-human who has fallen in with a pack of private school boys who love each other too much and who have come to love you too. Personal because each of those boys is such a separate human, and for me, identifying with Ronan was instant, lovely, horrible, and above all like looking in a mirror. Each of these kids is damaged, trauma lingering in the creases or out in the open, and each of them needs to learn to grow up and be less of a tire fire… Except I’m willing to bet each reader is going to stick to one harder than the rest, depending on their own anxieties and needs and gender and modes of communicating (or failing to).

There’s the moment I was sold, too:

But that wasn’t what happened. What happened was they drove to Harry’s and parked the Camaro next to an Audi and a Lexus and Gansey ordered flavors of gelato until the table wouldn’t hold any more bowls and Ronan convinced the staff to turn the overhead speakers up and Blue laughed for the first time at something Gansey said and they were loud and triumphant and kings of Henrietta, because they’d found the ley line and because it was starting, it was starting. (234)

It was here, the halfway point of the novel where all of their separate threads come together, that I lost my breath the first time and thought: all right, then. It’s starting—meaning both their inescapable and honest passion for each other as a group, and the path to loss that it puts them all on. The second time, it rang like a bell; the page before, Gansey observes the group with Blue added and knows it’s right, utterly right, like a lock snapping shut. The reader feels it, too, in the careful choice of words and deeds and expressions for each of these strange handsome creatures.

It’s hard, as a reader, not to fall as instantly and ridiculously in love—to not feel caught up in the pull of it—with each of them, with the pack of them, with the encompassing attraction of it.

Of course, this is just the start.

And then there’s the critical half: the part where I’d like to crow about the delicacy and subtlety Stiefvater manages to imbue her text with while still telling a straightforward quest story with romance and secrets and awkwardness. I felt like I’d been tricked in the most delicious way possible, believing I would be reading some sort of paranormal YA love triangle stuff and ending up with something complex, messy, queer, and sprawling instead. Gender, to come back to it, is one of the strongest points of The Raven Boys: the presence of women in the world of this book, though our fivesome is built up of Blue and her four dudes, is good. Also, the boys’ initial casual and unremarkable sexism is a grounding and realistic touch that I thought added a depth to them as people and to their welcoming of Blue into their world.

Because these are all boys who think they’re smart and together and not total dicks; it takes them being faced with a girl who’s grown up in a world of strong and brilliant woman to knock them down a peg on some of their blindness and privilege. It’s possible, after all, to be fond of women and girls and to believe one is an ally—while also living in an echo chamber of teenage masculinity that lets a lot of things pass unnoticed. Wrapping all of that up in a few lines of dialogue and gestures? That’s damn fine writing.

Gender is also significant in that Ronan, Gansey, Adam, and Noah are all developed with care, specifics, and attention to their different sorts of masculinity. This is going to sound strange, but: I often find that male characters aren’t well realized in some types of romantic plots, as if it’s impossible to be loved and be real at the same time. As a genderqueer human, I get frustrated in both directions; boys should be real, too. Stiefvater neatly avoids that problem by being clear that this is about love, but it’s about complex messy love with different shapes, tones, and types—including and especially between the boys themselves. It’s about being real more than being ideal, and in this book, everyone’s still trying to figure that out about each other. The relationships are the thing that makes The Raven Boys, and the Cycle as a whole, spectacular. Scenes like Gansey finding Ronan in the church, afraid he’s attempted to kill himself again, are so important; also small things, like the lines:

Gansey had once told Adam that he was afraid most people didn’t know how to handle Ronan. What he meant by this was that he was worried that one day someone would fall on Ronan and cut themselves.

It’s a thousand careful details that make these folks all so, so real.

They’ve got families; they’ve got trauma; they’ve got school and work; they’ve got money or not. They’ve got panic attacks and fear of mortality and fear of each other’s mortality. It’s brutally intense on an emotional level sometimes, and that’s the reason I think it’s worth pursuing—this book is just the start, the moment where it all starts rolling. There’s still so much more. I’m boggled at how much I feel like I’ve experienced in the course of four-hundred pages; it contains so much on both direct and implicit levels. Stiefvater is king of making a few careful words do the work of a whole paragraph, or more.

This also applies to class, one of the central concerns of the series: Blue and Adam come from Virginia poverty, in different ways, while Ronan and Gansey are stunningly wealthy. Adam—as well as Blue—has a complex relationship to the power of money and the stamp of class in society; neither lets their friends do things on their behalf. Adam desperately and jealously wants to outrun it and make himself one of those golden boys, while Blue is more baffled by it, though also wounded by the impossibility of her dreams of going to a good school for environmental science. These are, again, not “issues” in the book—they’re just the real color of the world.

The plot is compelling, too, though far more direct and simpler than the huge emotional web that drives it all. Noah Czerny is charming and tragic; the scene at his abandoned car with its Blink-182 stickers and aftermarket effects covered in seven years of debris (“murdered” and “remembered”) is chilling. The fact of his being dead but lingering isn’t just a party trick; it’s a very real thing with rules, consequences, and it isn’t cute or pleasant. Once Blue arrives in their lives and the one-year clock starts ticking down, everything is going too fast and too slow, a pleasure so intense it’s a pain. But it also includes adults, adversaries, and the world outside of their pack—something that makes the action feel reasonable and the world like a real one too.

And did I mention the fucking prose? Because we’re going to get back to that, I promise, as we move on to The Dream Thieves: the book where it all starts to get far more explicitly big-time queer, and I have a lot of personal feelings about everything that happens.

II: With me or Against Me: Queer Experience in The Dream Thieves

The significant thing about The Dream Thieves—Ronan’s book, in many ways—is that it’s one of the best actual representations of queer experience and coming to terms with one’s sexuality that I’ve ever had the pleasure of reading. The focus on recovering from trauma and forging a functional self out of the wreckage, too, is powerful—not just for Ronan, but for his companions as well. It works because it isn’t what the book is about; it’s something that happens during and across and spun into the things the book is about. There’s no signposting of “hm, I am gay”—it’s all about feeling, experience, the life that moves around you while you realize who you are one thread at a time, in perhaps not the most healthy or recommended of ways.

I’ve felt the most attachment to Ronan for a variety of reasons—having been one myself, it’s hard not to spot a kindred spirit—but predominant among them is that Stiefvater writes his eccentricities, his hyper-masculine tendencies, his raw broken intensity, with such care and attention. It isn’t enough to tell me that a character drinks; that he has some issues with loss and communication; that he needs to get out of himself with fast cars and faster friends and danger; that he’s running from something in himself as much as the world around him—show me.

I’ve felt the most attachment to Ronan for a variety of reasons—having been one myself, it’s hard not to spot a kindred spirit—but predominant among them is that Stiefvater writes his eccentricities, his hyper-masculine tendencies, his raw broken intensity, with such care and attention. It isn’t enough to tell me that a character drinks; that he has some issues with loss and communication; that he needs to get out of himself with fast cars and faster friends and danger; that he’s running from something in himself as much as the world around him—show me.

And she does. Same with his burgeoning sexuality, his secrets from others and himself, his attraction to Adam and Kavinsky in equal and terrifying measures. It’s “moving the emotional furniture around” while the reader isn’t looking, as she’s commented before about her prose style, and it works amazingly well. His struggle with himself could so easily be an Issue Story, or he could be a Typical Badass Dude, but neither of those happens.

Ronan Niall Lynch is just a guy, and he’s a guy with a lot of shit to work out about himself. I sympathize. Most of this essay is about to veer off into the territory that struck me most, reading the novel again, and that’s all about Ronan and Kavinsky. There are a thousand other spectacular things happening here—between Adam and Blue, Adam and Gansey, Gansey and Blue, everyone and Noah, and also the adults—but there’s a central relationship outside of the fivesome that makes this book something special.

The aesthetic between Ronan and Kavinsky hovers in the neighborhood of: Catholic guilt, street racing, cocaine, personal emptiness, raw unpleasant intense relationships, being complicated and fucked up together. Failure to communicate. Failure to connect, acting out as a result. I could write a dissertation about the relationship between these two; I’ll try to narrow it down. There’s a tendency to underwrite Kavinsky in the fandom discourse—or, equally frustrating, to cut him far more slack than is safe or healthy. It’s odd to call a character who does things like scream “WAKE UP, FUCKWEASEL, IT’S YOUR GIRLFRIEND!” at Ronan subtle, but: there we have it. I’d argue that Stiefvater’s building of his character is as subtle and careful and brilliant as anything; it’s just that it’s easy to miss in the gloss and noise and intensity of his persona. Ronan, in fact, often does miss it—and we’re mostly in his head, but we’re capable as readers of understanding the things he fails to parse when he sees them. It also allows us to see Ronan—all of him, good and bad—far more clearly than we ever have before.

He’s the most complex of the raven gang, I would argue, because of this: his life outside of them, without them, where he does things that aren’t all right. There are implications aplenty in the scenes with he and Kavinsky alone together, as well as in their constant through-going interactions (the aggressive gift-giving, the texting, the racing), of the things that Ronan keeps from Gansey and the side of the world he thinks of as “light.”

Because there’s antagonism, between them, but it’s the kind of antagonism that covers over something far closer, more intimate, and more intense. It’s an erotic exchange, often, distinctly masculine and sharp; Ronan himself, with the smile made for war, is filling some part of himself with Kavinsky that is important to him. The complex tension between these two young men reflects a lot of self-loathing and rage and refusal to engage with feelings in a productive manner. I’d point to the text messages, the careful cultivation of disinterest or the performance of aggression—offset by the volume of them, the need of them. It’s flirting; it’s a raw and horrible flirting, sometimes, but there’s no mistaking it for anything but a courtship. Keep it casual, except it’s anything but.

From the early scene in Nino’s where Kavinsky gifted Ronan with the replica leather bands and then “slapped a palm on Ronan’s shaved head and rubbed it” as a farewell, to their race later on where Ronan tosses the replica shades he’s dreamed up through Kavinsky’s window, observing after he wins and is driving away, “This was what it felt like to be happy,” there’s a lot of buildup. However, as Ronan is still living with his “second secret”—the one he hides even from himself, the one that can be summed up with I am afraid—it’s all displaced: onto the cars, onto the night, onto the adrenaline of a fight.

Remember: our boy is a Catholic, and it’s a significant part of his identity. We might get lines about Kavinsky like,

He had a refugee’s face, hollow-eyed and innocent.

Ronan’s heart surged. Muscle memory.

—and we might get them from the start, but it takes the whole journey for Ronan to get to a point where he can admit the tension there for what it is. He does the same with his jealousy of Adam and Gansey in the dollar store, later; Noah understands, but Ronan himself has no idea why he’s so livid that Gansey’s voice might change when Adam calls on the phone, why it’s too much to see Gansey as an “attainable” boy.

All of this, of course, comes to a head after Kavinsky and Ronan fall finally into each other’s company without Gansey to mediate—because Gansey has left Ronan behind to take Adam to his family’s gathering, and Ronan does things that come naturally to him without supervision. The two spend the weekend together in a wash of pills and booze and dreams, the climax of which is chapter 44: dreaming the replacement for Gansey’s wrecked car.

The first attempt is a failure; however, when Ronan is upset, Kavinsky makes a fascinating attempt to comfort him—first by saying, “Hey man, I’m sure he’ll like this one […] And if he doesn’t, fuck him,” and then by reminding Ronan that it took him months to perfect his dreamt Mitsubishi replicas. When Ronan is determined to try again, Kavinsky feeds him a pill:

“Bonus round,” he said. Then: “Open.”

He put an impossible red pill on Ronan’s tongue. Ronan tasted just an instant of sweat and rubber and gasoline on his fingertips.

A reminder that these are the smells that Ronan has earlier commented he finds sexy; also, if the tension in the scene isn’t clear enough to the reader, Kavinsky then waits until Ronan is nearly passed out and runs his fingers over his tattoo, echoing the earlier sex-dream. However, when he dreams the correct car, he immediately tells Kavinsky he’s leaving to return it to Gansey, and:

For a moment, Kavinsky’s face was a perfect blank, and then Kavinsky flickered back onto it. He said, “You’re shitting me.” […] “You don’t fucking need him,” Kavinsky said.

Ronan released the parking brake.

Kavinsky threw up a hand like he was going to hit something, but there was nothing but air. “You are shitting me.”

“I never lie,” Ronan said. He frowned disbelievingly. This felt like a more bizarre scenario than anything that had happened to this point. “Wait. You thought—it was never gonna be you and me. Is that what you thought?”

Kavinsky’s expression was scorched.

After this, when Kavinsky gifts him the dreamt Mitsu, the note he leaves reads: This one’s for you. Just the way you like it: fast and anonymous. Gansey blows past it with a comment on Kavinsky’s sexuality, but there’s real judgment in that joke—that Ronan used him like a dirty hookup and then went back home like nothing happened. It meant something to Kavinsky; it didn’t to Ronan.

Because ultimately, Kavinsky is a kid with a drug problem and a very bad family life who desperately wants Ronan—the person he sees as his potential partner, someone to be real with, maybe the only someone for that—to give a shit about him. “With me or against me” isn’t some sort of grand villain’s statement, it’s a codependent and wounded lashing out in the face of rejection. If he can’t have the relationship he wants, he’ll take being impossible to ignore instead. It’s also worse than simple rejection: it’s that Kavinsky has given himself to Ronan, has been open and real with him, has been intimate with him—and Ronan uses him then leaves.

To be clear, I don’t intend to justify his ensuing actions—they’re flat out abusive, and intentionally so—but I do think it deserves to be noted that Ronan does treat him with a remarkably callous disregard. Perhaps it’s because he doesn’t see how much Kavinsky is attached to him. Or, more accurately, neither one of them are capable of communicating in a productive or direct fashion about their attraction to each other; it’s all aggression and avoidance and lashing out. Perhaps it’s because he thinks there’s going to still be a future where he can balance both Kavinsky and Gansey in different halves of his life.

Except he’s wrong about that, and he pushed too far, took too much, and broke the one thing left that was keeping Kavinsky tethered to bothering to be alive. Kavinsky kills himself to make it a grand fucking show, and he does it to be sure Ronan knows he’s the reason. Which is, again, wrong—deeply, deeply wrong; it isn’t Ronan’s responsibility to make anyone else’s life worth living—but also real and tragic and awful. This all comes out in their confrontation in the dreaming forest of Cabeswater, when Ronan tries to convince Kavinsky that there’s no reason to do this—that life’s plenty worth living, et cetera.

“What’s here, K? Nothing! No one!”

“Just us.”

There was a heavy understanding in that statement, amplified by the dream. I know what you are, Kavinsky had said.

“That’s not enough,” Ronan replied.

“Do not say Dick Gansey, man. Do not say it. He is never going to be with you. And don’t tell me you don’t swing that way, man. I’m in your head.”

The implication being, of course, that Kavinsky could be with him. Ronan even has a moment, there, together, where he thinks about how much it has mattered to have Kavinsky around in his life, but it’s too late. He’s dead shortly thereafter, going out on the line, “The world’s a nightmare.” It’s the tragic arc at the center of The Dream Thieves—the titular one, in fact. This is a novel about Ronan and Kavinsky, and the things Ronan knows about himself at the close of the book. I’ve seen some folks argue that they think Kavinsky is a sort of mirror for Ronan himself, but I’d disagree: if anything, he’s a dark mirror of the things Ronan wants, the things he loves. He’s the opposite side of the coin from Adam and Gansey. He offers Ronan an equal sort of belonging, except in the “black place just outside of the glow.” Bonus round: he died thinking that no one human being believed he was worth a damn, after Ronan used him and left him.

It doesn’t excuse anything he does, but it gives everything a hell of a lot of aching depth.

Also, one further point of consideration: as readers, it is simple to identify with Gansey and see Kavinsky as worthless, as bad for Ronan, et cetera. (The substance party scene and aftermath are spectacular characterization for Gansey as someone who is capable of fire and cruelty and callousness, while he also feels overwhelming affection for Ronan at the same time.) However—Kavinsky thinks Gansey is bad for Ronan. From his perspective, Gansey is holding Ronan back from being the person who he most is at heart; he sees it as a codependent and controlling relationship, and he hates it, because he doesn’t appreciate seeing Ronan Lynch on a leash. He sees Gansey’s control as belittling and unnecessary, paternalistic. It’s rather clear—the scene with the first incorrectly-dreamed Camaro, for example—that he thinks Gansey doesn’t appreciate Ronan enough, that he would do better by him, treat him how he deserves to be treated.

Of course, he isn’t asking Ronan’s opinion about that—and he is firmly not a good person; if nothing else, his blatant disrespect for consent alone is a massive issue. But there’s a whole world in Kavinsky’s brashness and silences and horrible efforts at honesty, attraction, something close to obsession or devotion. It’s subtle, but it’s there, and it enriches the whole experience of The Dream Thieves to pay close attention to it. It’s Kavinsky’s suicide that drives Ronan to the significant moment where he admits that he “was suddenly unbearably glad to see Gansey and Blue joining him. For some reason, although he had arrived with them, he felt as if he had been alone for a very long time, and now no longer was.” He also, immediately, tells Matthew that he’s going to divulge all of their father’s secrets. Because he no longer hates or fears himself or the secrets inside him.

I’ve also glossed over a significant portion of the text, though, in digging into this one specific thing. It’s just a specific thing that strikes me as unique about this novel, and is another example of the rewards the Cycle offers for reading closely, reading deeply, and paying very close attention to every bit of prose. Stiefvater, as I’ve said before, balances a straightforward quest plot with an iceberg of emotional significance. The surface is handsome and compelling, but the harder you think the further you go, and it keeps on getting more productive.

A few further points, though: this is also the point at which it begins to become clear that this isn’t going to be a typical love triangle sort of thing. Noah and Blue’s intimacy, Gansey’s relationship with Ronan, the strange rough thing Adam and Ronan have between them, Blue and Adam’s falling out—this is a web of people, not a few clashing separate relationships. It’s got jealousy to go around between them all, too, something I found refreshing and realistic. So, on top of being a book about queerness and coming to terms with oneself, it’s also about the developing pile of humans that is the raven gang and their passion for each other as a group, rather than only as separate pairs or clumps.

Within the first fifteen pages comes one of the series’ most-referenced quotes:

“You incredible creature,” Gansey said. His delight was infectious and unconditional, broad as his grin. Adam tipped his head back to watch, something still and faraway around his eyes. Noah breathed woah, his palm still lifted as if waiting for the plane to return to it. And Ronan stood there with his hands on the controller and his gaze on the sky, not smiling, but not frowning, either. His eyes were frighteningly alive, the curve of his mouth savage and pleased. It suddenly didn’t seem at all surprising that he should be able to pull things from his dreams.

In that moment, Blue was a little in love with all of them. Their magic. Their quest. Their awfulness and strangeness. Her raven boys.

It doesn’t seem like much, but it’s the center-piece that is continually built upon: that there’s love here—and rivalry and passion and jealousy, too—but most intensely love. Also, on the second read, the way Stiefvater parallels Ronan and Blue is far more noticeable: from their reactions to Kavinsky, as the only two who seem actually familiar with him as a human outside of the context of his mythology, to their opposite but equal prickliness and readiness to go to bat for things, et cetera.

Adam is also a heartbreaking wonder in this book. He’s trying to be his own man, too young and hurt and tired to do so on his own but unwilling to bend the knee to accept help from anyone either. He’s also coming to terms with his abuse and his own tendencies toward rage and lashing out—again, Kavinsky makes an interesting counterpoint to Adam in Ronan’s life and desires (see, for reference, the sex dream). Gansey’s passion for his friends and his inability to care for Adam in the way Adam needs to be cared for are illustrated spectacularly well, here.

To be honest, though Ronan is a focal point and the character I discussed most, each of the raven gang does a lot of unfolding and growing in this novel; it’s in painful bursts and clashes, but it’s all there. The plot, again, moves through some fascinating paces as well—the scene at the party, where the chant goes up about the raven king while Adam is falling apart under the pressure from Cabeswater, is chilling to say the least.

The thing about these books is: icebergs. The second read offers up a thousand-and-one brief snips of prose and implication and mountainous backstory that reward the careful eye, the thoughtful head, and the engaged heart. I’m having a great time going back through, let me just tell you.

The plot that The Dream Thieves sets up, though, comes to a head more directly in Blue Lily, Lily Blue—so that’s where we’ll head next, also.

III: Kin and Kind in Blue Lily, Lily Blue

Blue Lily, Lily Blue, the third novel of The Raven Cycle, is in many ways a book about women—mothers, sisters, cousins, family, kin—and the structures of their lives, including men or not, love or not, each other or not. It’s an interesting counterpoint to the (immensely satisfying and beautifully realized) treatment of masculinity in The Dream Thieves. It also means—buckle up folks—that the thing I’ve been chomping at the bit to talk about but haven’t fit in as much during the past two sections of this essay is about to be the focus: Blue Sargent, mirror and amplifier and linchpin, a ferocious and delightful young woman who’s attempting to give as good as she gets for her raven boys and her family. And then some.

While there’s a strong argument to be made for these novels having four protagonists—Blue, Ronan, Adam, Gansey—and a few more point-of-view characters besides, there’s also little doubt that Blue is the one who ties it all together, the girl at the center of the room (though she often doesn’t feel like it). In a lesser execution of this sort of plot, it would be like a reverse harem-anime: one girl, four dudes, romantic entanglements abound, et cetera.

While there’s a strong argument to be made for these novels having four protagonists—Blue, Ronan, Adam, Gansey—and a few more point-of-view characters besides, there’s also little doubt that Blue is the one who ties it all together, the girl at the center of the room (though she often doesn’t feel like it). In a lesser execution of this sort of plot, it would be like a reverse harem-anime: one girl, four dudes, romantic entanglements abound, et cetera.

But as discussed in the previous sections, this is not that—it is the furthest from that it could be, and the fivesome are all balanced against and with each other in a tight-knit web of affection, need, and almost-bottomless adoration. It’s a big pile of humans, and that becomes more and more clear in Blue Lily, Lily Blue. When Orla, Blue’s older cousin, is attempting to intervene in her relationships to save her a little heartbreak, it leads Blue to admit something to herself that shapes the rest of the book, and retroactively the books that came before it:

“You can just be friends with people, you know,” Orla said. “I think it’s crazy how you’re in love with all those raven boys.”

Orla wasn’t wrong, of course. But what she didn’t realize about Blue and her boys was that they were all in love with one another. She was no less obsessed with them than they were with her, or one another, analyzing every conversation and gesture, drawing out every joke into a longer and longer running gag, spending each moment either with one another or thinking about when next they would be with one another. Blue was perfectly aware that it was possible to have a friendship that wasn’t all-encompassing, that wasn’t blinding, deafening, maddening, quickening. It was just that now that she’d had this kind, she didn’t want the other.

Stiefvater is also careful to realize this in the text: each section and part and pair of the group has a different dynamic, as discussed before, and none of these are given less passion or interest than the others. Noah’s relationship with Blue—affectionate and tinged with sorrow—is complicated by the fact that her energy magnifies him, including the parts of him that are becoming ever-less-human. Gansey’s relationship with Blue is made up of not-kisses and holding each other and the sharp claws of preemptive grief that dig into her guts when she looks at him, but it’s also about seeing each other as strange magnificent unique creatures. Blue and Adam have had their ugly go-rounds but are working back to something else; Ronan and Blue are too, too alike in their wit and razorblade edges.

And then there are the three- and moresomes, Adam-Gansey-Ronan for one. It’s all so complex and complexly realized, and Blue knows that: knows that this is all she wants, all she needs, even if it can’t last and the knowledge that it’s going to end is tearing her apart. This becomes especially prescient after Persephone’s death: without fanfare, without buildup, just sudden and unexpected and final. But we’ll come back to the rest of them, because Blue is the centerpiece of this book, and I want to think about her in a little more depth.

While the first book is about meetings and being the young charming kings of Henrietta, and the second book is about deepening those relationships and falling into a hell of a lot of trouble, this third installment is in many ways a book about growing up. Or, if not growing up, growing into oneself and the world one is destined for or striving towards. Each person is becoming something more, while the others watch; or, in the case of Noah, becoming less while the other fear for him. (Noah is the pop-punk ghost of my heart, ps.)

Blue, in particular, does a lot of growing in this book. She comes to understand herself and her raven boys in far more depth and honesty than she ever has before—and she also has to care for herself more with her mother gone and her household in disarray. Blue has always been close with Maura; this is not the sort of book where parents are insignificant. And now Maura has left—left her daughter, her friends, her lover Mr. Gray—with no warning. Colin Greenmantle is breathing down their necks, ready to burn their lives down around them if he isn’t satisfied with getting the Greywarren while his much more dangerous wife Piper sets out to find the third sleeper (the one who shouldn’t be woken).

It’s also becoming clear that these five are, actually, something more in terms of magic or destiny. Blue has always felt herself to just be a useful tool—a magnifier, but nothing special herself—until she meets Gwenllian, the entombed daughter of Glendower whom they wake. Gwenllian is a “mirror,” in magical terms, and tells Blue that she is too: she’s a witch, a mirror, a powerful woman. (Malory, too, the aged professor who has a service dog to help deal with anxiety, sees Blue’s aura as specifically magical.) It’s also notable that Gwenllian has a frantic, sharp-edged distaste for men; she is quite clearly a firm believer in women being for women and having each other’s back against the war-whispers and treachery of the men around them.

It isn’t so far from Blue herself, teaching Adam about the reason she hates when old men tell her she has nice legs—even if he doesn’t understand why she’s mad, at first. She’s been raised in a world of women, and now is a friend only to these boys, these young men she adores; however, in this book, she also branches out to hold those women more closely to herself. Losing her mother has made her appreciate the kinship of 300 Fox Way more, in some sense, and to become more of an independent creature on her own.

She has her own dreams and is, ultimately, coming into her own power—and her own right to love freely, love wildly, without giving her principles away in the process. She doesn’t take any shit, but that’s not a quirky personality trope. She has no patience for bullshit, no patience for meaningless things when there’s more important work to be done on the horizon; she also has an endless capacity for wit and creativity and sorrow. She’s a rich young woman, rich in love though not money, fighting to make a place for herself. She mirrors Adam in some regards, in terms of class and survival; she mirrors Ronan in others, in terms of her fierceness; she and Gansey share the kind of intensity that lets him teach her wordlessly to drive the Pig up and down an empty road all night.

She’s a linchpin. She’s a mirror. She’s got a switchblade and a lot of determination and the fear, aching at the core of her, that it’s all going to fall apart. But she’s going to do her level best, regardless, and isn’t going to give up or give in: not to fate, not to rules, not to patriarchy. She’s a girl after my own heart, and this is her book—appropriately, a book about growing and becoming a more magnified, specific version of oneself. The insights Stiefvater drops in through her characters about the process of suddenly finding oneself to be an adult are also sharp and perfect. I felt, at the close of this book, much like Adam and the others have throughout it: that somehow when they weren’t looking, “starting” to happen became “happened”—and they’re no longer older children but young adults, on the cusp of something magnificent or horrible.

Adam and Ronan’s relationship also develops significantly and intensely in Blue Lily, Lily Blue. While it has always been an understated but real connection—one of the first asides we get in The Raven Boys is about them being scabbed from dragging each other on a moving dolly behind the BMW; they share a rough-and-ready bond that is different from the love either of them feels for Gansey—it has evolved sharply over a very short period of time, in part because of two things. The first is that Ronan admits to himself his secret at the end of The Dream Thieves (being, he is attracted to men and in particular is attracted to Adam Parrish) and the second being that Adam is coming into his own as Cabeswater’s magician, as a man, as a human who is knowing himself more and more truly and with confidence.

Also, he has realized that Ronan is attracted to him and doesn’t mind one little bit. It’s a maddening, quickening slow build of a relationship that has its bedrock in their love for their friends, their friendship with each other, and their prickly roughness. It’s about respect. I have a particular appreciation for finally seeing them interact with each other separate from the group, also: Ronan visiting Adam at the mechanic’s shop to gift him hand crème, Ronan taking Adam to The Barns to show him how he’s been trying to wake his father’s dream creatures, Ronan dreaming him a mixtape for his car, Ronan pushing him in a shopping cart and wrecking it so they’re in a slightly-bloody pile together. Adam letting Ronan sleep in his room above the church (as we find out when Gansey shows up in his pajamas there one night and Adam is, briefly and tellingly, surprised it isn’t Ronan).

They also plot and execute Greenmantle’s downfall via blackmail together, which involves a spectacularly complex scene in the church. Adam has asked Ronan to dream up a lie: to frame Greenmantle using dreamed evidence for a series of grisly murders. Ronan doesn’t want to, because he’s not a liar, but Adam convinces him—and it doesn’t go well. But it also leads to one of the most stunning lines of Adam reflecting on Ronan in the series, the simple aside: “It was possible that there were two gods in this church.”

It’s all the small thousand scenes we’ve missed between them before, or had hinted at, suddenly on screen to show us the care Ronan takes with Adam—the care Adam is beginning to be able to allow him to take. Because Adam, partly due to Ronan’s specific brand of aggressive and unspoken affection, has begun to realize that his previous insistence on his own bootstraps was foolishness. This is Adam’s greatest growth, as shown ultimately in the moment where Gansey and Ronan show up to the courthouse at his father’s hearing to stand behind him:

Was it okay? Adam had turned down so many offers of help from Gansey. Money for school, money for food, money for rent. Pity and charity, Adam had thought. For so long, he’d wanted Gansey to see him as an equal, but it was possible that all this time, the only person who needed to see that was Adam.

Now he could see that it wasn’t charity Gansey was offering. It was just truth.

And something else: friendship of the unshakable kind. Friendship you could swear on. That could be busted nearly to breaking and come back stronger than before.

Adam help out his right hand, and Gansey clasped it in a handshake, like they were men, because they were men.

It is this growth—Adam coming into his own as a powerful magician and holder of the ley line, Adam about to graduate under his own power from Aglionby, Adam being there for his friends—that allows the group to begin to succeed at their quest. It is his effort to repair his friendship with Blue that saves his life, with Noah’s help too, in the scrying mishap that reveals Maura’s location; it is his mentorship under Persephone that gives him the skillset to act on his instincts. He’s not trying to be Adam Parrish, unknowable army of one, but Adam Parrish, part of a friend- and kin-group. It’s beautiful, really. And it pays off, in the climax, as they’re charting the cave system, pairing he and Ronan’s gifts to make the way easier: “This was their job, Adam realized. This was what they had to offer: making it safe for the others. That was what they had promised: to be Gansey’s magicians.”

Also, Adam knows that Gansey is the one fated to die; Ronan doesn’t. Blue does. She and Adam have bonded again over their love for that impossible boy-king and their desire to save his life at all costs. If anything is going to save any one of them, it’s love, and watching that deepen is stunning. He also notes, tellingly, “It was amazing she and Ronan didn’t get along better, because they were different brands of the same impossible stuff.” (I’m unsure if Adam is aware of the implication here, but the reader has a hard time missing it: Adam has a type, indeed.)

He’s also not quite right about Blue and Ronan, whose friendship is also more developed here in fits and starts. It’s true that Stiefvater parallels them a great deal, but in doing so, she makes it clear that what it’s possible for them to have together is no less intense than what they share with the others. At the scene in the cave, when it’s Blue and Ronan alone, she realizes that he loves her just as true as he does the other boys; it’s heartbreaking and handsome.

This all, of course, makes the knowledge that Gansey is fated for death before the year’s out the most horrifying and hard-edged thing in the series. This quickening, maddening love is the strongest these folks might ever feel, and it’s currently rather doomed. Blue and Gansey have fallen hard for each other; they’ve also fallen hard for their boys, their loved ones, their family as built together, and in the close of the cycle, some of that is bound to fall apart.

Noah, for one, has been deteriorating steadily and violently into something less human and more ghostly as the cycle goes on. I worry for his continuing existence; I worry, also, for Gansey—the boy weighed down under his kingship, the role he’s slipping into without knowing, the unseated in time feeling he lives with, his panic attacks and his fierce love and his fiercer terror. The pair of them are a fascinating duet, a little song of life and death all bound up in each other.

And I expected, to be honest, that we’re going to lose one, at this point in the series—if not both. Three is a powerful number, after all. I’d rather it be five at the end, but I found myself fearing that it might be three: Gansey’s magicians and his mirror, alone after it all.

Safe as life.

We find out, of course, in The Raven King, the next and final novel, in which the Cycle draws to a close, and all of these rich tumultuous young lives will turn out how they turn out. Rereading the first three books, I ache for them, for the intensity and the loss of this, for the passion and connection these five delightful humans have to each other and the life they’ve built. I ache for Blue wanting to go away to a college she can’t afford; I ache for Noah being murdered and dead and deteriorating; I ache for Gansey’s hollowness; I ache for Adam’s hard growing; I ache for Ronan’s neutron-star density of love and devotion that he can’t speak out.

But, as with the fivesome, there’s love also—always and also.

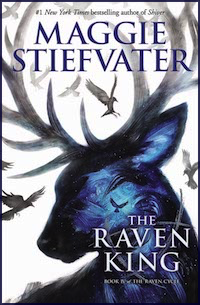

IV: That’s All There Is: Time and Closure in The Raven King

The thing about a cycle: it has to close. There must be a moment where the loop joins back onto itself and completes an arc, a thought, a feeling. The Raven King, fourth and final book in Stiefvater’s Raven Cycle, brings us around to the conclusion of the quest and its attendant conflicts. The previous three sections of this essay were written before the finale; this, the last section, is written after. I read it once for speed (you can read my separate review here), then a second time to savor—and here we are, wrapping up the whole thing together.

The Raven Boys gave us a quest, a fivesome, a burgeoning love. The Dream Thieves spun out the raw, rough, handsome interiors of our protagonists: their magic, their desires, their trauma. Blue Lily, Lily Blue makes real the strange shift into adulthood and becoming a family together, a sprawling sort of family with webs of love and jealousy built in. All three novels explore passion, loss, change; all three are complex and emotionally provocative, icebergs with half the work of the text hidden under the surface and blooming in the spaces of unspoken thoughts, unsaid words.

The Raven Boys gave us a quest, a fivesome, a burgeoning love. The Dream Thieves spun out the raw, rough, handsome interiors of our protagonists: their magic, their desires, their trauma. Blue Lily, Lily Blue makes real the strange shift into adulthood and becoming a family together, a sprawling sort of family with webs of love and jealousy built in. All three novels explore passion, loss, change; all three are complex and emotionally provocative, icebergs with half the work of the text hidden under the surface and blooming in the spaces of unspoken thoughts, unsaid words.

And this, The Raven King, is where it all comes to fruition.

The thematic arc of this final book is the natural step that follows Blue Lily, Lily Blue. Having settled in as a family together, and in doing so faced the flaws and fears that have been holding them back, it’s time for these young, dynamic adults to move through those traumas and come out the other side. The Raven King is very much a story about recovery and healing, of time and closure. It offers each of our protagonists the opportunity to overcome and grow through the agonies that they’ve been carrying inside them like weights. Stiefvater constructs, here, a paradigm for returning to the site of trauma and acclimating to it, pushing through, developing coping mechanisms and support systems. It’s an important and vital argument to make with a text this complex and emotionally resonant.

Ronan is able to reclaim the Barns, where his father died, for himself; he is able to laugh again, to speak with his brothers as a family again, to let himself ignite the ocean of his passion for Adam without fear. He still thinks about his father, and he thinks about Kavinsky—almost constantly, there’s a background refrain of the people whom he couldn’t save—but it drives him to do better, be better, rather than hating himself. There is a line, about his nightmares and “the ugly thrill of nearly being dead,” that acknowledges that killing himself was certainly part of the deal for quite a long time. While Gansey moves past the believed-suicide-attempt once he knows it was a dream consequence, in truth it was more of an active process than Ronan would like to admit. However, he is no longer the boy who wants to die; he’s a young man who wants to live and dream of light.

Adam, for whom love was a dangerous privilege, is able to open himself up to trusting his friends and trusting Ronan as his lover. He goes back to the parents who abused him and holds them accountable for his trauma. He is able to control himself and his magic, but also to let go—to look at horrible memories and allow them to pass, to acknowledge his wounding and his lashing out and his fear without letting them drag him down. Adam is a wonder of a young man; his arc is slow and subtle and excellent, as he grows up into a richer and surer version of himself. He has his college dreams and his home to return to. He is able to be all things, but also to be known. To do so, he must know himself, and continue to seek out better versions of that self.

Blue, much like Adam, is able to let go of some of her preconceptions about allowing people to help her and allowing love in—because she has known love in her family, but she has also known the horror of her curse and the weight of secrets, the pull to hold herself back from intimacy to protect her heart. She grows past her insecurities over being nothing-much as she realizes she’s truly something-more, and that is both beautiful and powerful. She will go with Henry Cheng and Gansey on their road trip; she will love and be loved and make a family that can be left and returned to, just like Adam. Leaving doesn’t mean never coming back, after all, and it’s healthy to be able to go. She’s finding a path that’s different from the one she might have imagined, but it’s a path that lets her be truly herself. In fact, her self-concept has changed—as we see in the hilarious but poignant scene where both Henry and Gansey pull up in their fancy cars to her high school and she must evaluate that perhaps she is the kind of person who’d rather hang out with raven boys.

And Gansey: Gansey with his true-blue PTSD and carefully controlled masks, his sense that he cannot allow himself to be weak or feel that he is wasting his privileges. This is a young man who tries to clamp down on his panic attack at Raven Day not for himself, but to avoid shaming his family; that single moment reveals so much of his core-deep wounds and insecurities. Fear and trauma have left Gansey hollow, unable to see himself or others beneath expectations and performances, until his passion for his friends and their needs ultimately ignites his will to survive. Gansey returns to the site of his death and there finds his king; in finding his king, he finds that the true purpose of his future is his companions, the great bright true thing between them. He also finds his second death, and this one has purpose: to preserve the magic and delight of his loved ones, to give them a future, to be the sort of king who sacrifices himself for the greater good.

Then there’s Noah—Noah Czerny, the boy who dreamed of ravens flocking and fighting in the sky, the catalyst for it all. He is a soft subtle lingering shadow in The Raven King, too weak for much but strong enough to hold on, hold on, be there at the exact moments he is needed. It was never Glendower; it was always Noah Czerny, whose greatest affections and closest joys come after his death, with these four people who complete and carry him to the moment of his dissolution. Without Noah, there would be no Gansey; without Noah, there would have been nothing to push them all to find each other; if they hadn’t found each other, they wouldn’t have loved each other, and Cabeswater wouldn’t have been able to rebuild Gansey’s soul out of pieces and shades of theirs.

From the first, time doubling back, it was always already Noah Czerny: the cheerfully prattling Aglionby student, the frightful poltergeist, the charming handsome soft-punk kid who is and has been there for Blue, for Adam, for Ronan, for Gansey. He has left marks on them all, some literal and some psychological, and he won’t be forgotten (though I will note, again, the strange imbalance of no one mentioning him in the epilogue). I suspected, based on the shape of the cycle, that it would be Noah who would ultimately die for Gansey to survive: the doubling of the sacrifice, the making of the sacrifice. I hadn’t suspected that Cabeswater would also be part of that sacrifice, but it’s perfect and beautiful.

Of course, in the first book, Gansey thinks that it feels like something has shifted into place when he meets Blue. It has. Time is an ocean, and in this ocean, Gansey the Third—oh, how clever, Maggie Stiefvater—is a version built of bits and bobs of his companions. He does, ultimately, look like Adam on the inside as he wished for. He also look like Ronan, and Blue, and Noah. He slips through time, but he holds on to them above all. Because, as it has been from the first, it’s about a love so great that it can sustain them; it’s about becoming together, and being together, in all the complex myriad fashions humans can connect themselves. As Blue observes,

It was not that the women in 300 Fox Way weren’t her family—they were where her roots were buried, and nothing could diminish that. It was just that there was something newly powerful about this assembled family in this car. They were all growing up and into each other like trees striving for the sun. (48)

Though it was said in jest—and frankly I laughed for a good straight five minutes after I saw the person’s post—the observation that the plot of The Raven King is genuinely “the real Glendower was the friends we made along the way” isn’t inaccurate. The Cycle is a bravura performance in its representation of the functions and purposes of affection, passion, honest attachment: Stiefvater spends four books exploring the weight, the taste, the texture of all sorts of love. It is understated and blinding; it is moving, devastating at times, but all for the good. These books argue a thousand things about giving and getting love, though perhaps the most salient is that to be loved is to be known.

The introduction of Henry Cheng works because he’s able to know Gansey and Blue, from the first. He appeals to a space in them that is something like the space filled by Noah—or the space Kavinsky held for Ronan, if Kavinsky had been less broken and miserable, less unable to share and cope. Henry’s speech in the hidey-hole, after all, isn’t so far from dying’s just a boring side effect. It’s a little heart-breaking for me, because of that. Henry is redeemed before he comes on scene, but K wasn’t given a shot at redemption. It speaks to the inevitability of loss and the failures of attachment in a powerful and necessary fashion, but it also hurts.

And speaking of, Ronan, our protagonist from one angle, is the most direct about needing to be known. Kavinsky attempts to know him—attempts to love him, as discussed in the second section of this essay—and it goes poorly. The inclusion, constant and thorough, of that failed relationship in Ronan’s chapters was significant to me; it wouldn’t have rung true for it to have slipped. He thinks of K, in his nightmare, second to his father in terms of people lost. The image of the sunglasses returns to him as well. The epilogue also delivers a surprise blow on that score: I had thought I was done being upset, until Ronan sends Gansey, Henry, and Blue to the car graveyard for the original dreamt Pig. It’s the one without the engine that Kavinsky insisted was good, that no one should be disappointed by, that Ronan was spectacular for making. The one that Ronan rejected as not good enough, as he then rejected Kavinsky, having used him for his own needs first.

The thing is: Blue adores it. The car was good enough, the dream was good enough. Implication is sharp, here, that perhaps Ronan has come around to realize the enormity of his mistake in that moment. It’s too late to take it back—it was too late from the moment he left—but it’s a point to grow from for him. He’s able, in part, to come to terms with his relationship with Adam and take more care due to the catastrophic failure of this previous attempt to know and be known. I appreciate, though, that even in this, he hasn’t forgotten or erased Kavinsky from his own self narrative, from his own history. It’s responsible and adult, it aches, and the implication that he isn’t going to get over it is powerful for me—because while it’s never a person’s fault when someone else commits suicide, Ronan’s casual cruelty was certainly a catalyst. He was careless, and it cost; he won’t be careless again, and he can do something to preserve the good memories as well.

There’s also the echo, once more, of the erotic dream from the second book, with Kavinsky and Adam each touching him and claiming to know him. Kavinsky echoes it in touching Ronan’s back sensually during the dreaming-weekend; Adam, in the Barns, finally echoes it as well as he traces the tattoo and puts his fingers to Ronan’s mouth. The position Ronan offers his partners in these scenes is telling, as well: his dreams are of giving his back to someone, of letting himself be vulnerable with them, and he does so in reality as well. It’s also rather telling that each scene, the dream and the night at the Barns, ends with the phrase, “He was never sleeping again.” (An aside: this is also remarkably tasteful, in handling sexuality and intimacy without cutting short the passion of it.)

Though one would expect this novel to be more about Gansey and Blue—and it is about them too, of course—a great deal of time is spent on the page between Adam and Ronan as their relationship finally comes to fruition. I strongly appreciate that Stiefvater gives them a rich, full, tender relationship based on knowing and illuminating each other’s most honest parts. As it has been from the first, Adam keeps Ronan honest and Ronan allows Adam to be a darling total asshole; they balance and counterbalance and support each other in private spectacular fashion. I’m not asking him to stay, only to come back, Ronan thinks of Adam near the close: a moment that acknowledges so much, as Ronan is primarily afraid of being left. He’s a boy made into raw edges by too much loss, too constant a trauma against his own tendency to love hugely and brightly. That he’s able to come to understanding that leaving isn’t permanent brought tears to my eyes.

Truly, there are months of argument to be made about the relationships and the character development in this Cycle. I could go on, and on, and on, and not run out of ground to cover in single lines, breathing moments, implications. It’ll have to be sufficient to note that the Raven Cycle, as closed out here, is perhaps one of the most intimate and honest things I’ve ever had the pleasure to read. It’s charming and light at times—but it also has depth and magic, a stunning clever intensity of observation and skill that renders each line real and true.

I’m disappointed that there isn’t space to linger over each moment in this closing book: the friendship between Blue and Ronan that runs deep and sure under the surface—creatures of the same magical stuff, after all—or the fact that the greatest hope of Ronan’s heart is to refinish floors and take care of cattle with his dreamt daughter and his lover, for example. Adam driving the BMW to confront his parents. The toga party, and Cheng2 getting extravagantly high to talk politics at it. Gansey coming to terms with his own magical abilities; the Gray Man insisting that Adam is the king and protagonist to Maura. The women of 300 Fox Way scrying for Persephone in the bathtub—Persephone, third met on the roadside—and explaining to Blue that she’s going places, that there’s no shame in letting her boys help her do it. “Parrish always was a creepily clever little fuck,” from Declan, in approval and admiration. “If you combined these two things—the unfathomable and the practical—you were most of the way to understanding Adam Parrish.” The genuine terror of 6:21, of the body-horror of Adam’s wayward hands and eyes, the refusal of all of his friends to do a single thing to hurt him given how he’s already been hurt.

It’s all so much. It leaves me with a sense of wonderment and loss balanced in counterpoint, hurt and delight, the joy so great it’s sorrow and the taste of the future like lightning in the air. Ronan dreamt up one Cabeswater already and he’s lying down to dream them a second at the close of the book: knowing that there are more adventures to be had when his loved ones return to him, holding down the home fires at the Barns. The Henry-Gansey-Blue unit—and what a fascinating development that was—are off to see the country in their gap year, since survival against all odds happened. Adam has Niall’s BMW and Ronan’s worship—he’s going places, but he’ll be back.

As a passionate defense of the significance of love, all shades and colors of it, the Raven Cycle deserves pride of place on the shelves of my home and heart. It speaks deep and true and personally to me, and to so many others: there’s a little of everyone here, a person whose trauma is your trauma and whose loves are your loves, and an arc to follow them through with bated breath. It’s over but it isn’t over; it’s closed but open, and these fanciful lovely creatures will go on together, together, together.

Safe as life, indeed.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.