It is a bitter winter, and civil war is ravaging Kurald Galain. Urusander’s Legion prepares to march on the city of Kharkanas. The rebels’ only opposition lies scattered and weakened—bereft of a leader since Anomander’s departure in search of his estranged brother. The remaining brother, Silchas Ruin, rules in his stead. He seeks to gather the Houseblades of the highborn families to him and resurrect the Hust Legion in the southlands, but he is fast running out of time…

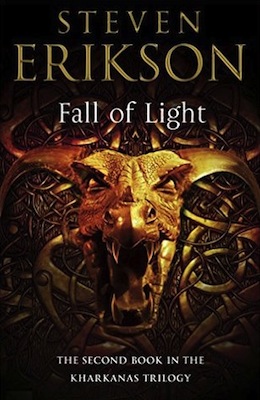

Steven Erikson returns to the Malazan world with Fall of Light, the second book in a dark and revelatory new epic fantasy trilogy, one that takes place a millennium before the events in the Malazan Book of the Fallen series. Available April 26th from Tor Books, Fall of Light continues to tell the tragic story of the downfall of an ancient realm, a story begun in the critically acclaimed Forge of Darkness. Read chapter two below, or head back to the beginning with chapter one!

TWO

Barely a smudge against the gloom, the sun was fading in the sky over the city of Kharkanas. The two lieutenants from the Houseblades of Lord Anomander, Prazek and Dathenar, met on the outer bridge and stood leaning on one of its walls, forearms on the stone. Like children, their upper bodies were tilted forward as they looked down upon the waters of the Dorssan Ryl. To their right, the Citadel stood like a fortress of night, defying the day. To the left, the city’s jumbled buildings crowded up against the flood wall as if caught in the act of marching over the edge.

Below the two men, the river’s surface was black, twisting with thick currents. Even now, the occasional charred tree trunk slid past, like the swollen limb of a dismembered giant. Ash-grey mud crusted the sheer walls that made up the banks. The boats moored to iron rings in the walls, near the stone steps that reached down into the water at intervals, looked neglected, home to dead leaves and murky pools of rainwater.

‘There is discipline lacking,’ murmured Prazek, ‘in our sordid post upon this bridge.’

‘We are looked down upon,’ Dathenar replied. ‘See us from atop the tower. We are small things upon this frail span. Witness as we betray errant curiosity, not suited to sentries at all, and in our pose you will find, with dismay, civilization’s slouching departure from the world.’

‘I too saw the historian at his lofty perch,’ Prazek said, nodding. ‘Or rather, his hooded regard. Did it track us out here? Does it fix still upon us?’

‘I would think so, as I feel a weight upon me. At least an executioner’s shroud offers mercy in hiding the face above the axe. We might splinter here under Rise Herat’s judgement, bearing as it does no less sharp an edge.’

Prazek was of no mind to argue the point. History was a cold arbiter. He studied the black water below, and found himself distrusting its depth. ‘A force to splinter us into dust and fragile slivers,’ he said, hunching slightly at the thought of the historian looking down upon them.

‘The river below would welcome our sorry fragments.’

The currents swirled their invitation, but there was nothing friendly in the sly gestures. Prazek shook his head. ‘Indifference is a bitter welcome, my friend.’

‘I see no other promise,’ Dathenar said with a shrug. ‘Let us list the causes of our present fate. I will begin. Our lord wanders lost under winter’s bleak cloak, and makes no bold bulge in his struggle—look out from any tower, Prazek, and you see the season unrelieved, settled flat by the weight of snow, where even the shadows lie weak and pale upon the ground.’

Prazek grunted, his eyes still fixed on the black waters below, half his mind contemplating that mocking invitation. ‘And the Consort lies swallowed in a holy embrace. So holy is that embrace, that there is nothing to see. Lord Draconus, you too have abandoned us.’

‘Surely, there is ecstasy in blindness.’

Prazek considered that, and then shook his head again. ‘You’ve not dared the company of Kadaspala, friend, else you would say otherwise.’

‘No, some pilgrimages I avoid by habit. I am told his self-made cell is a gallery of madness.’

Prazek snorted. ‘Never ask an artist to paint his or her own room. You invite a spilling out of landscapes one would not wish to see, for any cause.’

Dathenar sighed. ‘I cannot agree, friend. Every canvas reveals that hidden landscape.’

‘Manageable,’ said Prazek. ‘It is when the paint bleeds past the edges that we recoil. The wooden frame offers bars to a prison, and this comforts the eye.’

‘How can a blind man paint?’

‘Without encumbrance, I should say.’ Prazek waved one hand dismissively, as if to fling the subject into the dark water below. ‘So,’ he continued, ‘to the list again. The Son of Darkness walks winter’s road seeking a brother who chooses not to be found, and the Suzerain confides in the night for days on end, forgetting even the purpose of dawn, while we stand guard on a bridge none would cross. Where, then, the shoreline of this civil war?’

‘Far away still,’ Dathenar answered. ‘Its jagged edge describes our horizons. For myself, I cannot cleanse my mind of the Hust camp, where the dead slept in such untroubled peace, and, I confess, nor can I scour away the envy that took hold of my soul on that day.’

Prazek rubbed at his face, fingers tracking down from his eyes to rake through his beard. The water flowing beneath the bridge tugged at his bones. ‘It is said that no one can swim in the Dorssan Ryl now. It takes every child of Mother Dark down to her bosom. No corpse is retrieved, and the surface curls on in its ever-twisting smiles. If envy of the fallen Hust so plagues you, friend, I’ll offer no staying hand. But I will grieve your passing as I would my dearest brother.’

‘As I would your leaving my company, Prazek.’

‘Very well, then,’ Prazek decided. ‘If we cannot guard this bridge, let us at least guard each other.’

‘A modest responsibility. I see the horizons draw closer.’

‘But never to divide us, I pray.’ Prazek straightened, turning his back to the river and leaning against the wall. ‘I curse the poet! I curse every word and each bargain it wins! To so profit from beleaguered reality!’

Dathenar snorted. ‘An unseemly procession, this row of words you describe. This rut we stumble along. But think on the peasant’s language—as it wallows in its simplicity, off among the fields of fallow converse. Will the day begin in rain or snow? Does your knee ache, my love? I cannot say, dear wife! Oh and why not, husband? Beloved, the ache that you describe can have but one meaning, and on this morning lo! among the handful of words I possess, I cannot find it!’

‘Reduce me to grunts, then,’ said Prazek, scowling. ‘I beg you.’

‘We should so descend, Prazek. Each of us like a boar rooting in the forest.’

‘There is no forest.’

‘There is no boar, either,’ Dathenar retorted. ‘No, we hold to this bridge, and turn eyes upon the Citadel. The historian looks on, after all. Let us discuss the nature of language and say this: that power thrives in complexity, and makes of language a secret harbour. And in this complexity the divide is asserted. We have important matters to discuss! No grunting boar is welcome!’

‘I understand what you say,’ Prazek said, with a wry smile. ‘And so reveal my privilege.’

‘Just so!’ Dathenar pounded a fist on the stone ledge. ‘But listen! Two languages are born from one, and as they grow, ever greater the divide, ever greater the lesson of power delivered, until the highborn who are surely highbred are able to give proof of this, in language solely their own, and the lowborn who can but grunt in the vernacular are daily reminded of their irrelevance.’

‘Swine are hardly fools, Dathenar. The hog knows the slaughter awaiting it.’

‘And squeals to no avail. But consider these two languages and ask yourself, which more resists change? Which clings so fiercely to its precious complexity?’

‘Troop in the lawmakers and the scribes—’

Dathenar’s nod was sharp, a flush deepening to midnight on his broad face. ‘The educated and the trained—’

‘The enlightened.’

‘This is the warring tug of language, friend! The clay of ignorance against the rock of exclusion and privilege.’

‘Privilege—I see the root of that word, in privacy.’

‘A fine point you make, Prazek. Kinship among words can indeed reveal hints of the secret code. But here, in this war, it is the conservative and the reactionary that stand under perpetual siege.’

‘As the ignorant are legion?’

‘They breed like vermin.’

Prazek straightened and spread wide his arms. ‘Yet see us here, on this bridge, with swords at our belts, and bolstered in spirit by the eagerness of honour and duty. See how it wins us the privilege of giving our lives in defence of complexity!’

‘To the ramparts, friend!’ Dathenar cried, laughing.

‘No,’ his companion said in a growl. ‘I’m for the nearest tavern, and bedamned this wretched privilege. Run the wine down my throat until I slur like a swineherd!’

‘Simplicity is a powerful thirst. Words softened to wet clay, like paste squeezed out between our fingers.’ Dathenar’s nod was eager. ‘This is mud we can swim in.’

‘Abandon the poet then?’

‘Abandon him!’

‘And the dread historian?’ Prazek asked, smiling.

‘He’ll show no shock at our faithlessness. We are but guards huddled beneath the millstone of the world. This post will see us crushed and spat out like chaff, and you know it.’

‘Have we had our moment, then?’

‘I see our future, friend, and it is black and depthless.’

The two men set out, quitting their posts. Unguarded behind them stretched the bridge, making its sloped shoulder an embrace of the river’s rushing water—with its impenetrable surface of curling smiles.

The war, after all, was elsewhere.

* * *

‘It can be said in no other way,’ Grizzin Farl sighed, as he ran a massive, blunt fingertip through the puddle of ale on the tabletop: ‘she was profoundly attractive in a plain sort of way.’

The tavern’s denizens were quiet at their tables, and the air in the room was thick as water, gloomy despite the candles, the oil lamps, and the fiercely burning fire in the hearth. Conversations rose on occasion, cautious as minnows beneath an overhanging branch, only to quickly sink back down.

Hearing his companion’s faint snort, the Azathanai straightened in his seat, in the pose of a man taking affront. The wooden legs beneath him groaned and creaked. ‘What do I mean by that, you ask?’

‘If I—’

‘Well, my pallid friend, I will tell you. Her beauty only arrived at second, or even third, glance. Was a poet to set eyes upon her, that poet’s talent could be measured, as if on a scale, by the nature of his or her declamation. Would frenzied birdsong not sound mocking? And so impugn that poet as shallow and stupid. But heed the other’s song, at the scale’s weighty end, and hear the music and verse of a soul’s moaning sigh.’ Grizzin reached for his tankard, found it empty. Scowling, he thumped it sharply on the table and then held it out.

‘You are drunk, Azathanai,’ observed his companion as a server rushed over with a new, foam-crowned tankard.

‘And for such women,’ Grizzin resumed, ‘it is no shock that they do not consider themselves beautiful, and would take the mocking chirps as deserved, while disbelieving the other’s anguished cry. So, they carry none of the vanity that rides haughty as a naked whore on a white horse, the woman who knows her own beauty as immediate, as stunning and breathtaking. But do not think me unappreciative, I assure you! Even if my admiration bears a touch of pity.’

‘A naked whore on a white horse? No, friend, I would never query your admiration.’

‘Good.’ Grizzin Farl nodded, drinking down a mouthful of ale.

His companion continued. ‘But if you tell a woman her beauty emerges only after considerable contemplation, why, I think she would not sweetly meet the lips of your compliment.’

The Azathanai frowned. ‘You highborn have a way with words. In any case, do you take me for a fool? No, I will tell her the truth as I see it. I will tell her that her beauty entrances me, as it surely does.’

‘And so she wonders at your sanity.’

‘To begin with,’ the Azathanai said, belching and nodding. Then he raised a finger. ‘Until, at last, my words deliver to her the greatest gift I can hope to give her—that she comes to believe in her own beauty.’

‘What happens then? Seduced, swallowed in your embrace, another mysterious maiden conquered?’

The huge Azathanai waved a hand. ‘Why, no. She leaves me, of course. Knowing she can do much better.’

‘If you deem this worthy advice on the ways of love, friend, you will forgive the renewal of my search for wisdom… elsewhere.’

Grizzin Farl shrugged. ‘Bleed to your own lessons, then.’

‘Why do you linger in Kharkanas, Azathanai?’

‘Truth, Silchas Ruin?’

‘Truth.’

Grizzin closed his eyes briefly, as if mustering thoughts. He was silent for another moment, and then, eyes opening and fixing upon Silchas Ruin, he sighed and said, ‘I hold trapped in place those who would come to this contest. I push away, by my presence alone, the wolves among my kin, who would sink fangs into this panting flesh, if only to savour the sweat and blood and fear.’ The Azathanai watched his companion studying him, and then nodded. ‘I hold the gates, friend, and in drunken obstinacy I foul the lock like a bent key.’

Finally, Silchas Ruin looked away, squinting into the gloom. ‘The city has gone deathly quiet. Look at these others, cowed by all that is as yet unknown, and indeed unknowable.’

‘The future is a woman,’ said Grizzin Farl, ‘deserving a second, or third, glance.’

‘Beauty awaits such contemplation?’

‘In a manner of speaking.’

‘And when we find it?’

‘Why, she leaves you, of course.’

‘You are not as drunk as you seem, Azathanai.’

‘I never am, Silchas. But then, who can see the future?’

‘You, it appears. Or is this all a matter of faith?’

‘A faith that entrances,’ Grizzin Farl replied, looking down at his empty tankard.

‘I have a thought,’ Silchas Ruin said, ‘that what you protect is that future.’

‘I am my woman’s favourite eunuch, friend. While I am no poet, I pray she is content with the love she sees in my eyes. Utterly devoid of song is hapless Grizzin Farl, and this music you hear? It is no more than my purr beneath her pity.’ He gestured with the empty tankard. ‘Men such as I will take what we can get.’

‘You have talked yourself out of a night with that serving woman you so admired.’

‘You think so?’

‘I do,’ said Silchas. ‘Your last request for more ale surely obliterated this evening’s worth of flirtation.’

‘Oh dear. I must make amends.’

‘If not the common subjects of Mother Dark, there are always her priestesses.’

‘And wiggle the bent key? I think not.’

After a moment, Silchas Ruin frowned and leaned forward. ‘One of these barred gates is hers?’

Grizzin Farl raised a finger to his lips. ‘Tell no one,’ he whispered. ‘They’ve not yet tried the door, of course.’

‘I don’t believe you.’

‘My flavour hides in the darkness, whispering the disinclination.’

‘Do you think this white skin announces my disloyalty, Azathanai?’

‘Does it not?’

‘No!’

Grizzin Farl scratched at his bearded jaw as he contemplated the young nobleborn. ‘Well, curse my miscalculation. Will you dislodge me now? I am as weighty as stone, as obstinate as a pillar beneath a roof.’

‘What is your purpose, Azathanai? What is your goal?’

‘A friend has promised peace,’ Grizzin Farl replied. ‘I seek to honour that.’

‘What friend? Another Azathanai? And what manner this peace?’

‘You think the Son of Darkness walks alone through the ruined forest. He does not. At his side is Caladan Brood. Summoned by the blood of a vow.’

Silchas Ruin’s brows lifted in astonishment.

‘I do not know how peace will be won,’ Grizzin continued. ‘But for this moment, friend, I judge it wise to keep Lord Draconus from the High Mason’s path.’

‘A moment, please. The Consort remains with Mother Dark, seduced unto lethargy by your influence? Do you tell me that Draconus—that even Mother Dark—is unaware of what goes on outside their Chamber of Night?’

Grizzin Farl shrugged. ‘Perhaps they have eyes only for each other. What do I know? It is dark in there!’

‘Spare me the jests, Azathanai!’

‘I do not jest. Well, not so much. The Terondai—so lovingly etched on to the Citadel floor by Draconus himself—blazes with power. The Gate of Darkness is manifest now in the Citadel. Such force buffets any who would seek to pierce it.’

‘What threat does Caladan Brood pose to Lord Draconus? This makes no sense!’

‘No, I see that it does not, but I have already said too much. Perhaps Mother Dark will face the outer world, and see what is to be seen. Even I cannot predict what she might do, or what she might say to her lover. We Azathanai are intruders here, after all.’

‘Draconus has had more congress with Azathanai than any other Tiste.’

‘He surely knows us well,’ Grizzin Farl agreed.

‘Is this some old argument, then? Between Draconus and the High Mason?’

‘They generally avoid one another’s company.’

‘Why?’

‘That is not for me to comment on, my friend. I am sorry.’

Silchas Ruin threw up his hands and leaned back. ‘I begin to question this friendship.’

‘I am aggrieved by your words.’

‘Then we have evened this exchange.’ He rose from his chair. ‘I may join you again. I may not.’

Grizzin watched the nobleborn leave the tavern. He saw how others looked up at the white-skinned brother of Lord Anomander, as if in hope, but if they sought confidence or certainty in Silchas Ruin’s mien, the gloom no doubt defeated that desire. Twisting in his chair, Grizzin caught the eye of the serving woman, and with a broad smile he beckoned her over.

* * *

High Priestess Emral Lanear stepped up on to the platform and looked across to see the historian near the far wall, as if contemplating a leap to the stones far below. She looked round, and then spoke. ‘So this is your refuge.’

He glanced at her, briefly, from over a shoulder, and then said, ‘Not all posts have been abandoned, High Priestess.’

She approached. ‘What is it you guard, Rise Herat, demanding such vigilance?’

Shrugging, he said, ‘Perspective, I suppose.’

‘And what does that win you?’

‘I see a bridge,’ he replied. ‘Undefended, and yet… none dare cross it.’

‘I think,’ she mused, ‘simple patience will see a resolution. This lack of opposition is but temporary.’

His expression betrayed doubt. He said, ‘You assume a resolve among the highborn that I have yet to see. If they stand with hands upon the swords at their sides, they are turned against the man who now shares her dark heart. Their hatred and perhaps envy of Draconus consumes them. Meanwhile, Vatha Urusander methodically eliminates all opposition, and I do not sense much outrage among the nobility.’

‘They will muster under Lord Anomander’s call, historian. When he returns.’

He looked her way once more, but again only for a moment before his gaze skittered away. ‘Anomander’s Houseblades will not be enough.’

‘Lord Silchas Ruin, acting in his brother’s place, is already assembling allies.’

‘Yes, the gratitude of chains.’

She flinched, and then sighed. ‘Rise Herat, lighten my mood, I beg you.’

At that he swung round, leaned his back against the wall and propped his elbows atop it. ‘Seven of your young priestesses trapped Cedorpul in a room. It seems that in boredom they had fallen to comparing experiences at their initiations.’

‘Oh dear. What lure does he offer, do you think?’

‘He is soft, one supposes, like a pillow.’

‘Hmm, yes, that might be it. And the pillow invites, too, a certain angle of repose.’

The historian smiled. ‘If you say so. In any case, he sought to flee, and then, when he found his path to the door barred, he pleaded his weakness for beauty.’

‘Ah, compliments.’

‘But spread out among all seven women, why, their worth was not much.’

‘Does he still live?’

‘It was close, High Priestess, especially when he suggested they continue the conversation with all clothing divested.’

Smiling, she walked to the wall beside the man. ‘Bless Cedorpul. He holds fast to his youth.’

The historian’s amusement fell away. ‘While Endest Silann seems to age with each night that passes. I wonder, indeed, if he is not somehow afflicted.’

‘In some,’ she said, ‘the soul is a hoarder of years, and makes a wealth of burdens unearned.’

‘A flow of blood from Endest Silann’s hands is yet another kind of blessing,’ Rise observed, twisting round to join her in looking out upon the city. ‘At least that is done with, now, but I wonder if some life-force left him through those holy wounds.’

She thought of the mirror in her chamber, that so obsessed her, and there came to her then, following the historian’s words, a sudden fear. Does it steal from me, too? Thief of my youth? Or is time alone my stalker? Mirror, you show me nothing I would want to see, and like a tale of old you curse me with my own regard. She shrugged the notion off. ‘The birth of the sacred in spilled blood—I fear this precedent, Rise. I fear it deeply.’

He nodded. ‘She did not deny it, then.’

‘By that blood,’ said Emral Lanear, ‘Mother Dark was able to see through Endest’s eyes, and from it all manner of power flowed—so much that she fled its touch. This at least she confessed to me, before she sealed the Chamber of Night from all but her Consort.’

‘That is a precious confession,’ Rise said. ‘I note your burgeoning privilege, High Priestess, in the eyes of Mother Dark. What will you do with it?’

She looked away. At last they had come to the reason for her seeking out the historian. She did not welcome it. ‘I see only one path to peace.’

‘I would hear it.’

‘The Consort must be pushed aside,’ she said. ‘There must be a wedding.’

‘Pushed aside? Is that even possible?’

She nodded. ‘In creating the Terondai upon the Citadel floor, he manifested the Gate of Darkness. Whatever arcane powers he had, he surely surrendered them to that gift.’ After a moment she shook her head. ‘There are mysteries to Lord Draconus. The Azathanai name him Suzerain of Night. What consort is worth such an honorific? Even being a highborn among the Tiste is insufficient elevation, and since when did the Azathanai treat our nobility with anything but amused indifference? No. Perhaps, we might conclude, the title is a measure of respect for his proximity to Mother Dark.’

‘But you are not convinced.’

She shrugged. ‘She must set him aside. Oh, give him a secret room that they might share—’

‘High Priestess, you cannot be serious! Do you imagine Urusander will bow to that indulgence? And what of Mother Dark herself? Is she to divide her fidelity? Choosing and denying her favour as suits her whim? Neither man would accept that!’

Emral sighed. ‘Forgive me. You are right. For peace to return to our realm, someone has to lose. It must be Lord Draconus.’

‘Thus, one man is to sacrifice everything, but gain nothing by it.’

‘Untrue. He wins peace, and for a man obsessed with gifts, is that one not worthwhile?’

Rise Herat shook his head. ‘His gifts are meant to be shared. He would look out upon it as if from the wrong side of a prison’s bars. Peace? Not for him, that gift. Not in his heart. Not in his soul. A sacrifice? What man would willingly destroy himself, for any cause?’

‘If she asks him.’

‘A bartering of love, High Priestess? Pity is too weak a word for the fate of Draconus.’

She knew all of this. She had been at war with these thoughts for days and nights, until each became a wheel turning in an ever-deepening rut. The brutality of it exhausted her, as in her mind she set Mother Dark’s love for a man against the fate of the realm. It was one thing to announce the necessity for the only path she saw through this civil war, measuring the mollification of the highborn upon the carcass, figurative or literal, of the Consort, in exchange for a broadening of privilege among the officers of Urusander’s Legion, but none of this yet bore the weight of Mother Dark’s will. And as to that will, the goddess was silent.

She will not choose. She but indulges her lover and his clumsy expressions of love. She is as good as turned away from all of us, while Kurald Galain descends into ruin.

Will it take Urusander’s mailed fist pounding upon the door to awaken her?

‘You will have to kill him,’ Rise Herat said.

She could not argue that observation.

‘The balance of success, however,’ the historian went on, ‘will be found in choosing whose hand wields the knife. That assassin, High Priestess, cannot but earn eternal condemnation from Mother Dark.’

‘A child of this newborn Light, then,’ she replied, ‘for whom such condemnation means little.’

‘Urusander is to arrive to the wedding bed awash in the blood of his new wife’s slain lover? No, it cannot be a child of Lios.’ His gaze fixed on hers. ‘Assure me that you see that, I beg you.’

‘Then who among her beloved worshippers would choose such a fate?’

‘I think, on this stage you describe, choice has nowhere to dance.’

She caught her breath. ‘Whose hand do we force?’

‘We? High Priestess, I am not—’

‘No,’ she snapped. ‘You just play with words. A chewer of ideas too frightened to swallow the bone. Is not the flavour woefully short-lived, historian? Or is the habit of chewing sufficient reward for one such as you?’

He looked away, and she saw that he was trembling. ‘My thoughts but spiral to a single place,’ he slowly said, ‘where stands a single man. He is his own fortress, this man that I see before me. But behind his walls he paces in fury. That anger must give us the breach. Our way in to him.’

‘How does it sit with you?’ Emral asked.

‘Like a stone in my gut, High Priestess.’

‘The scholar steps into the world, and for all the soldiers that comprise your myriad ideas, you finally comprehend the price of living as they do, as they must. A host of faces—you now wear them all, historian.’

He said nothing, turning to stare out to the distant north horizon.

‘One man, then,’ she said. ‘A most honourable man, whom I love as a son.’ She sighed, even as tears stung her eyes. ‘He is all but turned away already, and she from him. Poor Anomander.’

‘The son slays the lover, in the name of the man who would be his father. Necessity delivers its own madness, High Priestess.’

‘We face difficulties,’ Emral said. ‘Anomander is fond of Draconus, and this sentiment is mutual. It is measured in great respect and more: it possesses true affection. How do we sunder all of that?’

‘Honour,’ he replied.

‘How so?’

‘They are two men who hold honour above all else. It is the proof of integrity, after all, and they choose to live that proof in all that they do.’ He faced her again. ‘A battle is coming. Facing Urusander, Anomander will command all the Houseblades of the Greater and Lesser Houses. And, perhaps, a resurrected Hust Legion. Paint this picture I offer, High Priestess. The field of battle, the forces arrayed opposite one another. Where, then, do you see Lord Draconus? At the head of his formidable Houseblades—who so efficiently annihilated the Borderswords? He will stand on his honour, yes?’

‘Anomander will not deny him,’ she whispered.

‘And then?’ Rise asked. ‘When the highborn see who would stand with them in the battle to come? Will they not in rage—in fury—step to one side?’

‘But wait, historian. Surely Anomander will blame his highborn allies for abandoning the field?’

‘Perhaps at first. Anomander will see that defeat is inevitable. Thus, there will be the humiliation of the surrender to Urusander, and he cannot but see the Consort’s gesture as the cause of that. A surrender forced by Draconus’s pride, and when the Consort remains unrepentant—he can do no other, as he will see the surrender as a betrayal, as he must; indeed, he will understand it as his own death sentence—then, Lanear, we see them set upon one another.’

‘The highborn will acclaim Anomander’s disavowal of that friendship,’ she said, nodding. ‘Draconus will end up isolated. He cannot hope to defeat such united opposition. That battle, historian, will be the last of the civil war.’

‘I love this civilization too much,’ Rise said, as if tasting the words for himself, ‘to see it destroyed. Mother Dark must never know any of this.’

‘She will never forgive her First Son.’

‘No.’

‘Honour,’ she said, ‘is a terrible thing.’

‘All the more egregious our crime, High Priestess, in forging a weapon in the flames of integrity, a fire we will feed until it burns itself out. You see him as a son. I do not envy you, Lanear.’

A voice screamed in her mind, rising up from her wounded soul. The pain that birthed that scream was unbearable. Love and betrayal on a single blade. She felt the edge turn and twist. But I see no other way! Must Kharkanas die in flames? Will Urusander’s soldiers be made into crass thugs, and as thugs take power unopposed, unchecked? Are we doomed to make lovers of war into our rulers? How soon, then, before Mother Dark reveals a raptor’s eyes, with talons gripping the arms of the throne? Oh, Anomander, I am sorry. Roughly, she wiped at her eyes and cheeks. ‘I will trap the crime in my mirror,’ she said in a broken voice, ‘where it can howl unheard.’

‘And to think how Syntara underestimates you.’

She shook her head. ‘No longer, perhaps. I have written to her.’

‘You have? Then it begins in earnest.’

‘We will see. She is yet to reply.’

‘Did you address her as an equal, High Priestess?’

She nodded.

‘Then you make your language familiar, in the ancient sense of the word. She will preen in that plumage.’

‘Yes. Vanity was ever the breach in her walls.’

‘We assemble a sordid list here, Lanear. When fortresses abound, we make sieges life’s daily habit. In such a world, we each stand alone at day’s end, and face in fear our barred door.’ The strain deepened the lines on his face. ‘A most sordid list.’

‘Each one a single step upon the path, historian. No longer can you hold to this post, high above the world. Now, Rise Herat, you must walk among the rest of us.’

‘I will write none of this. The privilege is gone from my heart.’

‘It is just the blood on your hands,’ she replied, without much sympathy. ‘When it is all said and done, you can wash them clean in the river below. And in time, as that river flows on and on, the truth will be dispersed, until none could hope to discern your crimes. Or mine.’

‘Then I will see you kneeling at my side on that day, High Priestess.’

She nodded. ‘If there can be whores of history, Rise, then we are surely in their company.’

He was studying her, with the face of a condemned man.

See now, woman? The mirrors are everywhere.

* * *

Step by step, pilgrims made a path. Seeking a place of tragedy deemed holy, or a site sanctified by nothing more than a truth or two scraped down to the bone, the ones who sought out such places transformed them into shrines. Endest Silann understood this now: that the sacred was not found, but delivered. Memory spun the thread, each pilgrim a single strand, stretched and twisted, spun, spun into life. It did not matter that he had been the first. Others among his priestly kin were setting out, into the face of winter, to arrive at the ruined estate of Andarist. They walked in his footsteps, but left no blood on the trail. They arrived and they stood, looking upon the site of past slaughter, but did so without comprehension.

Their journey, he knew, was a search. For something, for a state of being, perhaps. And in that contemplation, that silent yearning, they found… nothing. He imagined them stepping forward into the clearing before the house, walking around, eyes scanning the worthless ground, the crooked stones and the withered grasses that would grow thick and green in patches come the spring. Finally, they crossed the threshold, walking over the flagstones hiding the mouldering corpses of the slain, and before them, in the chill gloom, waited the hearthstone, now a sunken altar, with its indecipherable words carved upon its stone face. He saw them looking around, imaginations conjuring up ghosts, placing one here, another there. They sought, in the silence, for faint echoes, the trapped cries of loss and anguish. They took note, without question, of the black droplets of blood everywhere, not understanding their meandering way, not understanding Endest’s own senseless wandering—no, they would seek some vast meaning in that trail on the stones.

Imagination was a terrible thing, a scavenger that could grow fat on the smallest morsels. Hook-beaked, talons scraping and clacking, it lumbered about casting a greedy eye.

But in the end, it all meant nothing.

His fellow acolytes then returned to the Citadel. They looked on him with envy, with something like awe. They looked to him, and that alone was like the reopening of wounds, because there were no worthy secrets hiding in Endest’s memories. Every detail, already blurring and blending, was meaningless.

I am the priest of the pointless, seneschal to the hapless. You see my silence as humility. You see the wear in my face as some burden willingly taken on, and so give me a gravity of countenance I hardly deserve. And in your debates, you ever turn to me, seeking validation, revelation, a pageant of wise words behind which you can dance and sing and bless the darkness.

He could not tell them the source of his weariness. He could not confess the truth, much as he longed to. He could not say, You fools, she looked through my eyes and made them weep. She bled through my hands and saw in horror that it sanctified, dripping tears of power. She took hold of me only to then flee, leaving behind nothing but despair.

I will age as hope dies. I will bend to the weight of failure. My bones will creak to the crumbling of Kurald Galain. Do not look to my memories, my brothers and sisters. Already they twist with doubt. Already they take on the shape of my flaws.

No. Do not follow me. I but walk to the grave.

A short time earlier, while he sat on the bench of the inner garden, huddled against the bitter cold, beneath a thick cloak of bear fur, he had seen the young hostage, Orfantal, run alongside the fountain with its black frozen pool. The boy held a practice sword in one hand, and the dog, Ribs, ran beside him as if it had rediscovered its youth. Now free of worms, it had gained weight, that beast, and showed the sleek muscles of its hunting origins. Together, they played out imaginary battles, and more than once Endest had come upon Orfantal in his death-throes, with Ribs drawing close beside the boy as he lay on the ground, spoiling the gravitas of the scene with a cold wet nose snuffling against Orfantal’s face. He’d yelp and then curse the dog, but it was difficult to find malice in the love the animal displayed, and before long they would be wrestling on the thin carpet of snow.

Endest Silann was no indulgent witness to all of this. In the dull, halfformed shadows cast by child and dog, he saw only nightmares in waiting.

Lord Anomander had left the wretched house of his brother—scene of recent slaughter—in the company of the Azathanai High Mason, Caladan Brood. They had struck north, into the burned forest. Endest had watched them from the bloodstained threshold.

‘I will hold you to your promise of peace,’ Anomander had said to Brood, just before they left, when they all still stood in the house.

Caladan had regarded him. ‘Understand this, Son of Darkness, I build with my hands. I am a maker of monuments to lost causes. If you travel west of here, you will find my works. They adorn ruins and other forgotten places. They stand, as eternal as I could make them, to reveal the virtues to which every age aspires. They are lost now but will be rediscovered. In the days of a wounded, dying people, these monuments are raised again. And again. Not to worship, not to idolize—only the cynics find pleasure in that, to justify the suicide of their own faith. No, they raise them in hope. They raise them to plead for sanity. They raise them to fight against futility.’

Anomander had gestured back to the hearthstone. ‘Is that now another one of your monuments?’

‘Intentions precede our deeds, and then are left lying in the wake of those deeds. I am not the voice of posterity, Anomander Rake. Nor are you.’

‘Rake?’

‘Purake is an Azathanai word,’ Brood said. ‘You did not know? It was an honorific granted to your family, to your father in his youth.’

‘Why? How did he earn it?’

The Azathanai shrugged. ‘K’rul gave it. He did not share his reasons. Or, rather, “she”, as K’rul is wont to change his mind’s way of thinking, and so assumes a woman’s guise every few centuries. He is now a man, but back then he was a woman.’

‘Do you know its meaning, Caladan?’

‘Pur Rakess Calas ne A’nom. Roughly, Strength in Standing Still.’

‘A’nom,’ said the Son of Darkness, frowning.

‘Perhaps,’ the Azathanai said, ‘as a babe, you were quick to stand.’

‘And Rakess? Or Rake, as you would call me?’

‘Only what I see in you, and what all others see in you. Strength.’

‘I feel no such thing.’

‘No one who is strong does.’

They had conversed as if Endest was not there, as if he was deaf to their words. The two men, Tiste and Azathanai, had begun forging something between them, and whatever it was, it was unafraid of truths.

‘My father died because he would not retreat from battle.’

‘Your father was bound in the chains of his family name.’

‘As I will be, Caladan? You give me hope.’

‘Forgive me, Rake, but strength is not always a virtue. I will raise no monument to you.’

The Son of Darkness had smiled, then. ‘At last, you say something that wholly pleases me.’

‘Yet still you are worshipped. Many by nature would hide in strength’s shadow.’

‘I will defy them.’

‘Such principles are rarely appreciated,’ Caladan said. ‘Expect excoriation. Condemnation. Those who are not your equals will claim for their own that equality, and yet will meet your eyes with expectation, with profound presumption. Every kindness you yield they will take as deserved, but such appetites are unending, and your denial is the crime they but await. Commit it and witness their subsequent vilification.’

Anomander shrugged at that, as if the expectations of others meant nothing to him, and whatever would come from his standing upon the principles he espoused, he would bear it. ‘You promised peace, Caladan. I vowed to hold you to that, and nothing we have said now has changed my mind.’

‘Yes, I said I would guide you, and I will. And in so doing, I will rely upon your strength, and hope it robust enough to bear each and every burden I place upon it. So I remind myself, and you, with the new name I give you. Will you accept it, Anomander Rake? Will you stand in strength?’

‘My father’s name proved a curse. Indeed, it proved the death of him.’

‘Yes.’

‘Very well, Caladan Brood, I will take this first burden.’

Of course. The Son of Darkness could do no less.

They had departed then, leaving Endest alone in the desecrated house. Alone, with the blood drying on his hands. Alone, and hollowed out by the departing of Mother Dark’s presence.

She had heard every word.

And had, once more, fled.

He shivered in the garden, despite the furs. As if he had never regained the blood lost all that time past, there at the pilgrims’ shrine, he could no longer fight off the cold. Do not look to me. Your regard ages me. Your hope weakens me. I am no prophet. My only purpose is to deliver the sanctity of blood.

Yet a battle was coming, a battle in the heart of winter, upending the proper season of war. And, along with all the other priests, and many of the priestesses, Endest would be there, ready to dress wounds and to comfort the dying. Ready to bless the day before the first weapon was drawn. But, alone among all the anointed, he would possess another task, another responsibility.

By my hands, I will let flow the sanctity of blood. And make of the place of battle another grisly shrine.

He thought of Orfantal dying, in the moment before Ribs pounced, and saw the spatters of blood on the snow around the boy.

She had begun returning now, faint and silent, and with his eyes, the goddess etched the future.

That was bad enough by itself, but something he could withstand.

If not for her growing thirst.

Do not look at me. Do not seek to know me. You’ll not like my truths.

Step by step, this pilgrim makes a path.

* * *

Bedecked in his heavy armour, Kellaras stood hesitating in the corridor when Silchas Ruin appeared. The commander stepped to one side to let the lord past. Instead, Silchas halted.

‘Kellaras, have you sought entry into the Chamber of Night?’

‘No, milord. My courage fails me.’

‘What news do you bring that so unmans you?’

‘None but truths I regret knowing, milord. I have word from Captain Galar Baras. He has done as you commanded, but in the observation of his new recruits, he reiterates his doubt.’

Silchas turned to study the blackwood door at the corridor’s end. ‘No counsel will be found there, commander.’

I fear you are right. Kellaras shrugged. ‘My apologies, milord. I sought but could not find you.’

‘Yet you stepped aside and voiced no greeting.’

‘Forgive me, milord. All courage fails me. I believe what I sought in the Chamber of Night was a gift of faith from my goddess.’

‘Alas,’ said Silchas Ruin in a growl, ‘she makes faith into water, and pleasures in its feel as it drains from the hand. Even our thirst is denied us. Very well, Kellaras, I have your news, but it changes nothing. The Hust armour must be worn, the swords held in living hands. Perhaps this will be enough to give Urusander pause.’

‘He will know the measure of those in that armour, milord, and the fragility of the grasp upon those swords.’

‘You would spread the sand beneath your feet out and under my own, Kellaras, but I need to remain sure of each stride I take.’

‘Milord, any word of your brothers?’

Silchas frowned. ‘You think us eager to share such privacies, commander? Your lord will find you in good time, and yield no sympathy should your courage fail in his eyes. Now, divest yourself of that armour—its display whispers of panic.’

Bowing, Kellaras backed away.

Facing the Chamber of Night, Silchas Ruin seemed to hesitate, as if about to march towards it, and then he wheeled round. ‘A moment, commander. Send Dathenar and Prazek to the Hust, and charge them take command of the new cohorts, and so give answer to Galar Baras’s needs, as best we can.’

Startled, Kellaras asked, ‘Milord, are they to don Hust armour? Take up a Hust sword?’

Silchas Ruin’s face hardened. ‘Has courage failed everyone in our House? Leave my sight, commander!’

‘Milord.’ Kellaras quickly set off. As he marched up the corridor, he could feel Ruin’s baleful glare upon his back. Panic’s bite is indeed a fever. And here I am, the flea upon a thousand hides. He would return to his chamber and remove his armour, setting aside the girdle of war, but retain his sword as befitted his rank. Silchas was right. A soldier makes of his garb a statement, and an invitation. It was the swagger of violence, but inside that armour there could be diffidence and, indeed, great fear.

He would then set out and find Dathenar and Prazek where he had left them, upon the Citadel’s bridge.

Harbinger blades for those two, and a chorus of scales. Oh, my friends, I see you shrivel before my eyes at this news. Forgive me.

The Citadel’s darkness was suffocating. Again and again he found the need to pause and draw a deep, settling breath. In the corridors and colonnaded hallways, he walked virtually alone, and it was all too easy to imagine this place abandoned, haunted by a host of failures—no different, then, from any ruin he had visited out in the lands to the south, where the Forulkan left only their bones amidst the rubble. The sense of things still unfinished was like a curse riding an endless breath. It moaned on the wind and made stones tick in the heat. It whispered in the sifting of sand and voiced low laughter in the slip of pebbles between the fingers.

He could see this fortress devoid of life, a scorched shell that made Dark’s temple a bitter jest. Worshipped by spiders in their dusty webs, and beetles crawling through bat guano—a man wandering through such a place would find nothing worth remembering. The failings of the past cut like a sharp knife through any hope of nostalgia, or sweet reminiscence. He could not help but wonder at the impermanence of such places as temples and other holy sites. If nothing more than symbols of lost faith, then they stood as mortal failings. But if gods died in such ruins—if they felt a blade sink into their hearts, or slide smooth across their soft throats, then the crime was beyond any surrendering of faith.

Still, perhaps holiness was nothing more than an eye’s gift—upon these stones, or that tree, or the spring bubbling beneath it. Perhaps the only murder possible in such places was the one that left hope lying lifeless upon the ground.

Leaving his chamber and making his way towards the outer ward and the gate, beyond which waited the bridge, Kellaras was forced to cross the Terondai’s glittering pattern cut into the flagstones. He could feel the power beneath him, emanating in slow exudations, like the breath of a sleeping god. The sensation crawled across his skin.

He emerged into the chill night, where frost glistened on the stone walls and the lone Houseblade positioned at the gate stood huddled beneath a heavy cloak, dozing as she leaned against the barrier. Hearing his approach, she straightened.

‘Sir.’

‘You have closed the gate.’

She nodded. ‘I saw, sir, that the bridge was unguarded.’

‘Unguarded? Where, then, are Dathenar and Prazek?’

‘I do not know, sir.’

Kellaras gestured and she hurried to unbar the gate. The hinges squealed as she pushed on the portal. The captain passed through, on to the bridge. The bitter chill in this almost perpetual night was made all the more fierce by the black waters of the Dorssan Ryl. His boots cracked on ice as he hurried across the span.

He could well guess the refuge Dathenar and Prazek had found. Dereliction by officers was a grievous offence, and worse, the example it set could deliver a mortal wound to morale. Yet, in his heart, Kellaras could not blame his two friends. Their lord had abandoned them, and the one brother who remained to command the Citadel’s Houseblades often mistook birthright for wisdom: with this last command, written in the spinning of a heel, half the officers remaining to the Houseblades were divested of their colours.

Without question, Galar Baras and the Hust would welcome this gift, although Kellaras suspected that even his friend would be startled at the largesse, and perhaps wonder at Silchas Ruin’s unleavened generosity with respect to Anomander’s soldiers.

Attachment to any other force might be cause for envy, under the circumstances, but Kellaras was under no illusions, and he well knew the effect delivering this command would have upon Dathenar and Prazek. As good as banishment. And so it will seem, given their abandoning their post, and to be honest, I am loath to deny the connection. Officers, by the Abyss! No, it’s serendipitous punishment, enough to sober them to the quick.

The Gillswan was a tavern that made a virtue of its obscure location, down a curling slope to a loading dock and sunk into the foundations of a lesser bridge. The cobbles were uneven due to frost-heaving, all the more treacherous with the addition of frozen puddles filling the gaps left by missing stones. Despite this, the gloom failed in disguising the pitfalls, and Kellaras made his way to the low door without mishap. He pushed it open and felt smoky heat gust into his face.

Prazek’s voice crossed the cramped, crowded room. ‘Kellaras! Here, join us hogs in the swill! We are drunk in defeat, my friend, but see us welcome the woe and wallow of our fate!’

Kellaras saw his friends, leaning against one another on a bench backed by a wall. Ignoring the crowd of off-duty Houseblades, even those that called out in greeting, he made his way over to Dathenar and Prazek, pulled out a chair and sat down opposite them. Faces flushed, they smiled. Then Dathenar pushed a flagon towards the commander, and said, ‘It’s the beastly tongue that wags us this night, my friend.’

‘There is pomp to this circumstance nonetheless,’ Prazek said, lurching forward to rest his thick forearms on the table. ‘No highborn can truly sink into the hole of ignorance’s cloying mud. We poke our faces free again and again, gasping for air.’

‘If this fug be air,’ Dathenar said in a growl. ‘Besides, I am too drunk to swim, too bloated to drown, and too confused to tell the difference. We left the bridge—this much I know—and that is a crime in the eyes of our lord.’

‘Fortunate, then,’ said Prazek, ‘that our lord’s eyes are elsewhere.’

‘Unfortunate,’ corrected Kellaras, ‘since I must see in his stead.’

‘That will make any man’s eyes sting,’ Dathenar said.

‘I’ll not deny that,’ Kellaras replied, pointedly.

But neither man was in any condition for subtlety. With a broad, sloppy smile, Prazek waved one hand. ‘Must we take our posts again? Will you berate us with cold promises? At the very least, friend, build us a fine argument, an intricaspy—intricacy—of purpose. Hook fingers into the nostrils and drag out the noble horse, so we may see its fine trappings. Honour’s bridle—’

‘Pride’s stirrups!’ shouted Dathenar, raising his flagon.

‘Duty’s bit between the teeth!’

‘Loyalty’s over-worn saddle, so sweet under the cheeks!’

‘To take belch’s foul cousin—’

‘Friends,’ said Kellaras in a warning hiss, ‘that is enough of that. Your words are unfit for officers of Lord Anomander’s Houseblades. You try my indulgence. Now, be on your feet, and pray the cold night air yields you sobriety.’

Prazek’s brows lifted and he looked to Dathenar. ‘He dares it, brother! To the bridge, then! Torches approach from some dire quarter. ’Tis revelation’s light, to make every sinner cower!’

‘Not the bridge,’ Kellaras said, sighing. ‘You have been reassigned. Both of you. By command of Silchas Ruin. You are to join the Hust Legion.’

This silenced them. Looking upon their shocked expressions offered Kellaras no satisfaction.

‘F-for abandoning our posts?’ Prazek asked in disbelief.

‘No. That crime stays between us. The matter is more prosaic. Galar Baras has terrible need for officers. This is Ruin’s answer.’

‘Oh,’ muttered Dathenar, ‘it is indeed. Ruin, ruinous answer, ruin of all privilege, ruin of life. A command voiced with distinction—alas, we hear it all too well.’

‘Our privilege to do so,’ nodded Prazek, ‘in language less than obscure.’

‘More than plain, brother.’

‘Just so, Dathenar. See me long for sudden complexity. Wish me swathed in obfuscation and euphoric euphemism. I would flee to the nearest lofty tower, worthy of my hauteur. I would sniff and decry the state’s sordid… state, and then frown and announce: the wine is too tart. Too… too, far too… tart.’

‘I’ll whip the servant, brother, if that pleases you.’

‘Pleasing is dead, Dathenar, and dead… pleasing.’

Dathenar groaned and rubbed at his face. ‘Prazek, we should never have left unguarded the bridge. See what fate we let cross, when a mere switch would have sent the hog running. So be it. I yield to simple fate and name her just.’

Prazek pushed himself upright. ‘Commander Kellaras, we are, as ever, at your call.’

Grunting, Dathenar stood as well. ‘Perchance the sword has a bawdy tale, to amuse us in our perfidy. And the armour—well, it is said to be loquacious to a fault, but I’ll not begrudge the warning voice, even should we fail in heeding it.’

Standing, Kellaras gestured to the door. ‘Step carefully once outside, friends. The way back is uncertain.’

Both men nodded at that.

Excerpted from Fall of Light © Steven Erikson, 2016