Saruman the White is one of literature’s greatest wizards. Not so household a name in pop culture, perhaps, as Merlin, Harry Potter, or Gandalf himself, but nearly so. Fantasy readers might at least consider him a B-lister like Ged, Kvothe, Raistlin, or Elminster. Though he was set up in J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium as the eldest and most “high” of the Istari, the order of wizards, he plays second fiddle to Gandalf in every way that counts. And he knows it, and it eats him up. It defines him.

See, Saruman’s rise and fall is a tale of pride and mercy. If, like the dwarves, you delve too deep, deeper than the late Christopher Lee’s undeniably awesome portrayal of of the character in Peter Jackson’s films, deeper even than The Lord of the Rings and its Appendices, you find there are storied veins of insight—mythic ore, if not refined gems—in Tolkien’s other works about the character that make him all the more compelling. I refer mostly to 1977’s The Silmarillion and 1980’s Unfinished Tales. The former offers straight-up canon, the latter additional notes, essays, and even alternative versions of events. There is pity to be had, and understanding, even amidst Saruman’s corruption. The recurring themes of pride, pity, and mercy are woven throughout Tolkien’s epic story, in character arcs like Gollum’s, Boromir’s, and very much in Saruman’s.

The first to come was one of noble mien and bearing, with raven hair, and a fair voice, and he was clad in white; great skill he had in works of hand, and he was regarded by well-nigh all, even by the Eldar, as the head of the Order.

Saruman is a wizard of burning jealousy and dangerous pride, but you can sometimes feel sorry for him. Sort of like that White Council scene in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey when Gandalf and Galadriel totally dis him. He keeps pooh-poohing Gandalf’s claims about Dol Guldur and the return of the Enemy, but they’re not really listening to him (except maybe Elrond). Galadriel initiates her secret, hands-free teleconference with Gandalf while she orbits the scene and avoids having to make eye contact with Saruman, whose grumbles just fade into the background. (I like to think Elrond is at least politely nodding his head during this.) Sure, Saruman is trying to dissuade the Council from messing with his own inauspicious, ring-fuelled ambitions, and he really is a big jerk beneath it all, but you almost feel bad for the guy. No one is taking him seriously—which, yeah, they shouldn’t—as though we’ve already seen the Rings trilogy and know he turns bad. But that’s just in the movies, and its timeline is wonky.

When first we read of him, Saruman is mentioned only in passing: In regards to his early suspicions about Bilbo’s ring, Gandalf says, “I might perhaps have consulted with Saruman the White, but something always held me back.” Right there in that first line Tolkien sets a sour tone (or a villain’s minor key) for Saruman. Frodo remarks that he’s never heard of him and we, the first time reader, haven’t either.

“He is the chief of my order and the head of the Council,” Gandalf says with obvious deference, but even though Saruman’s treachery will not be revealed until twelve chapters later, there is clear hesitation—if not a trace of premonition—in Gandalf’s words. Something held him back from comparing notes with his boss? Indeed, for though he didn’t know of Saruman’s treason yet, he at least knew, and for a long time, that his nominal leader—and the first of the Istari to be chosen for their shared mission—was haughty. Dickish, even.

See, we never actually get to know Saruman as he had been for most of his very long life—2,019 years in Middle-earth up to this point, to say nothing of his life in the Undying Lands across the sea. He and the other four Istari wizards came to contest the power of Sauron, and it’s almost a shame that we don’t get to read about him before he went astray, to see him in his upstanding, more righteous state. I say almost, because Tolkien seemed never to have intended him to be a sympathetic character, given his sinister spin from the first use of his name. And yet…

And yet! If if you look beyond the principle narrative and into Tolkien’s further writings, you get a clearer picture about Saruman and his deeds before the War of the Ring. You don’t see a different character, just a multifaceted and more entangled one. The vainglorious titles that he gave himself in his hour of betrayal are a fitting metaphor for his fractured mind. He was not Saruman the White, but Saruman the Wise, Saruman Ring-maker, and Saruman of Many Colours!

In “The Council of Elrond,” when he speaks of his ordeal with Saruman, Gandalf observes that what he thought at first were robes of white were in fact robes woven of many colors which “shimmered and changed hue” when they moved. Saruman insists that white is for losers, for it can be dyed and overwritten, and that “white light can be broken.” But Gandalf, who we know to be the wiser, observes that “he that breaks a thing to find out what it is has left the path of wisdom.” So says one of the Wise to another. Basically throughout the trilogy, each of them keeps calling the other a fool, but only one of them seems to be making a contest out of it.

So what’s with these guys? In The Two Towers, after he has returned from death, Gandalf tells Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas that he, Gandalf, is Saruman—or rather “Saruman as should have been.” And this line happily made it into the films, too. I love this bit, because it begs some questions even though Gandalf is not in the habit of explaining the meaning behind his cryptic words. But he did say it: should have been. That, to me, is the weightiest line in the whole chapter, because it sums up yet barely scratches the surface of the ancient friendship—and enmity—of these two spirits. So who are these two staff-waving old geezers anyway?

All right, stop me if you’ve heard this one, which involves three wizards walking into a bar. Except instead of three it’s really five and instead of a bar it’s all of Middle-earth.

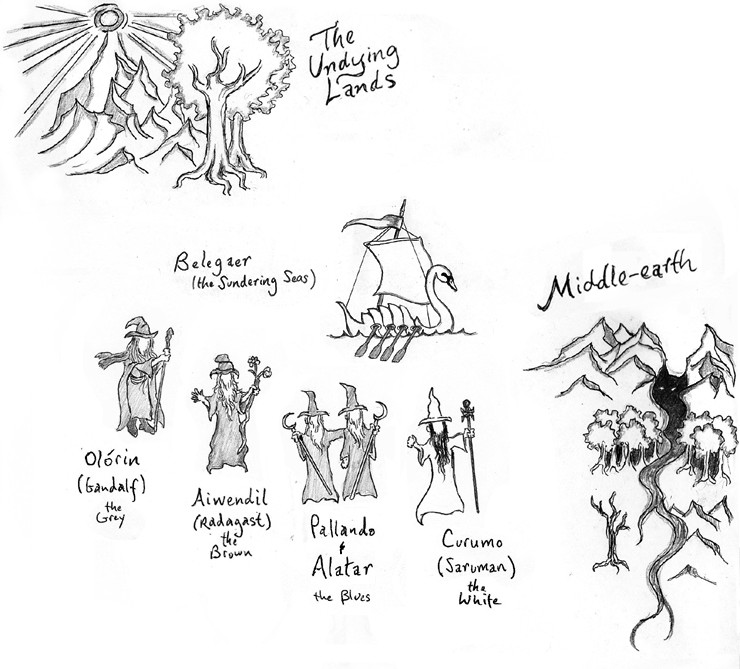

The wizards were from the start Maiar, an echelon of spiritual beings sent by Ilúvatar (the omnipotent creator of all things) to help the Valar (the uppermost spirits) shape the World. So, not human at all, not Men. For the First and Second Ages, two chaps in particular known as Curumo and Olórin got no mention at all. They played no starring role in the epic creation story, the rise and fall of Melkor (Sauron’s old boss), and the schisms of the Elves. Not even the forging of the Rings of Power or the first defeat of the Lord of the Rings himself.

But then a thousand years into the Third Age—which began the first time Sauron was defeated and the One Ring was taken from him by Isildur—Middle-earth’s biggest baddie began to stir and take shape again. Knowing that Sauron would become problematic to those still dwelling there, some of the Valar held a council to discuss the sending of three emissaries to assist them. Drawn from his father’s incomplete writings, this council is discussed briefly by Christopher Tolkien in Unfinished Tales. This, then, was the scene taking place in some unearthly Valinórean estate:

Who would go? For they must be mighty, peers of Sauron, but must forgo might, and clothe themselves in flesh so as to treat on equality and win the trust of Elves and Men. But this would imperil them, dimming their wisdom and knowledge, and confusing them with fears, cares, and weariness coming from the flesh.

Two of the Maiar volunteered right away: The first was Curumo, later to be called Saruman by Men. He was a Maia of Aulë. Aulë was the crafty, smith-like Vala; note that Saruman’s later predilection for crafting and machinery stems from this affiliation. The second was Alatar (one of the seldom-referenced “Blue wizards”), a Maia of Oromë—being the huntsman-flavored Vala. So they’re the only two who stepped forward. Then Manwë, the King of the Valar who had summoned the council in the first place, was the one who said—and I may be paraphrasing here—“Dude, what about Olórin? He’d be perfect for this mission! You know, that bloke in grey togs always on some journey or other?”

And so the Maia named Olórin, who would later be called Gandalf, walked in, still huffing and puffing from whatever his latest errand had been and probably tracking dirt in from the road. He sat at the edge of the gathering; I like to imagine he picked the squeaky chair everyone else avoided. He asked what was going on and what Manwë wanted him for. When the King of the Valar told him the plan, about their sending three emissaries to contest the Dark Lord, Olórin balked. He insisted that he was too weak for the task and was, truth be told, afraid of Sauron. That sold it for Manwë (“all the more reason why he should go”), who then commanded him to join up as the third member of the group.

But Varda, the Queen of the Valar, “looked up and said: ‘Not as the third;’ and Curumo remembered it.” Not the third, she said. Meaning what? Olórin was the third selected but first in…power? Might? Preference? Curumo took note of this. Right from the start, Curumo had showed initiative and boldly volunteered for the mission. Yet he observed that Olórin, who didn’t even want to go and even confessed fear of their opponent, was clearly the favored one. Nevertheless, Curumo did not begrudge him yet; being a proper Brit-invented character, Curumo showed a stiff upper lip. And as far as we know, he really did mean to challenge Sauron and do right by the Valar in the beginning. Indeed, he was regarded as “higher in Valinórean stature” than the rest, so from the start he was set up as the head of their order. He was the White Messenger.

Before they shoved off, the Valar selected two more Maiar to round up their party to a solid five. These two were Pallando and Aiwendil. Yavanna, the Vala of earthy and growing things, was fond of Aiwendil and had begged that he be allowed to join their quest. Aiwendel would later be named Radagast the Brown, and Curumo was irritated with him from the start, too. But where he envied Gandalf’s wisdom and high favor, he seemed to just regard Radagast as a buffoon and begrudged his presence. Tolkien doesn’t explicitly state it, but it’s obvious that Curumo rolled his eyes at having to babysit the animal-loving hippie wizard.

So these were the Istari, and off they went by boat to Middle-earth.

One at a time they arrived and were met on the West-shores by Círdan the Shipwright, an Elf who did play a part in earlier events of Middle-earth. The White Messenger was the first to arrive, followed by the two Blue wizards, then the Brown, and finally by the most reluctant of the group, the Grey. Now Círdan had Narya, one of the three Rings of Power made for Elves, and when Olórin came ashore he was secretly entrusted with it because Círdan was a good judge of character, divined him to be the wisest of the wizards, and was convinced that its power would be needed to help Olórin “for the kindling of all hearts to courage.”

And the Grey Messenger took the Ring, and kept it ever secret; yet the White Messenger (who was skilled to uncover all secrets) after a time became aware of this gift, and begrudged it, and it was the beginning of the hidden ill-will that he bore to the Grey, which afterwards became manifest.

Bingo! (Not to be confused with Bingo Baggins, Tolkien’s early name for Frodo, later relegated to one of Bilbo’s sillier uncles…) That was the last straw for Curumo, whose jealousy of Manwë’s favorite only increased with time. Then was he officially unhappy with this grey-clad upstart.

Once they were all together on Middle-earth, the Istari didn’t stick together like a D&D adventuring party (or boy band). In fact, they were free to carry out their mission—a very general one of working to help the peoples of Middle-earth counter the threat of Sauron—however they saw fit. Each of the emissaries had been selected by the Valar for their different “powers and inclinations” and could use them as they wished. Moreover, the Valar, like Ilúvatar, were big on free will. If that meant allowing the Istari to go their own ways, so be it!

And so Curumo, who was named Saruman by the Men of the north, went ever among said Men. He was sociable in the beginning, and his voice was ever persuasive. He and the two Blue wizards went into the East of Middle-earth, though there’s no account of what they did there or what became of the Blues at all.

Saruman eventually came back westward and the White Council was formed. Consisting of Saruman, Gandalf, Galadriel, Elrond, Círdan, and some other unnamed Elves, their purpose was essentially the same as the Istari’s: to organize against the movements of Sauron. Galadriel nominated Gandalf to be the head of the White Council but he declined—the Grey Pilgrim didn’t want to be tied down—so the position fell to Saruman. The responsible, reliable one. But oh, how he begrudged Gandalf for being the top choice yet again. Not that he revealed this. Saruman did not wear his emotions on his sleeve. Nor had he, even up until this point, fallen into evil yet. That was a slow descent.

It’s important to understand that the Istari were not infallible. Throughout Tolkien’s legendarium, very few are. As detailed in The Silmarillion, the Elves made many blunders and enacted terrible acts of pride and wrath. Melkor himself, most gifted of the Valar, became the source of evil in the world. Many of the Maiar spirits fell from the grace of their creator, seduced by Melkor—such as the Balrogs, and of course Sauron himself. So while Saruman was a Maia, the Istari, “being clad in bodies of Middle-earth, might even as Men and Elves fall away from their purposes, and do evil, forgetting the good in the search for power to effect it.” Which is exactly what he did.

As much as some would regard Gandalf as a goodie-two-shoes (certainly Saruman did), the point is that he could have been corrupted as well. When he identified the One Ring centuries later, he shied away from it precisely because he understood that nothing was free from evil if it desired power. The other wearers of the Three, Elrond and Galadriel, did not deign to touch it, for Middle-earth had a history of mighty beings doing terrible things even with good intention. Better to let a Hobbit carry it.

Eventually Saruman settled himself in Isengard, for he had befriended the people of both Rohan and Gondor during a time in their history where war had beleaguered them and he came with gifts and words of praise for their valor. Using that fair voice of his, he secured an impressive home: Happy to have such a learned wizard on their border to help them heal, Gondor’s steward gave him the keys to Isengard’s tower of Orthanc. As a holding of Gondor, Isengard even made Saruman an honorary lieutenant of the realm. “In this way,” Appendix A tells us, “Saruman began to behave as a lord of Men.”

Meanwhile, the Valar who sent the wizards had forbidden them to “reveal themselves in forms of majesty, or to seek to rule the wills of Men or Elves”; they were only to “advise and persuade” them to good. So was Saruman evil yet? Probably not. But he was slipping. Saruman’s area of expertise was ring-lore and the Enemy’s history, the better to counter the lord of all the rings. Not only had he now taken lordship over Men but the very reason Saruman sought to claim Orthanc was for its palantír, the Seeing Stone he would much later use to communicate with Sauron directly.

Saruman gazed a little too long into the abyss that was Sauron by studying him and his famous ring. Yet also was he ever mindful of what Gandalf, his secret rival, was up to. Which was a lot of guesswork, considering the Grey Pilgrim didn’t exactly share his whereabouts with anyone. Saruman’s jealousy grew to fear and hatred; like many who are deceitful, he suspected others of the same. And he wondered what Gandalf had guessed about his own mind. Moreover, Gandalf didn’t desire to be revered or even feared. Why not? He was a Maia, damn it. Perhaps he was just hiding it!

But one thing he’d learned about Gandalf, who he gainsayed at every opportunity (it had become Saruman’s MO): Gandalf sure loved the Shire and those quaint little Halfling folk. He wouldn’t shut up about them to whoever would listen. Saruman just smiled and nodded but he did listen. So Gandalf had adopted the Little People in some little pet project of his own—so what? They had nothing to do with the mission, or the Rings of Power, and therefore were irrelevant…unless they weren’t?

Saruman therefore decided to visit the Shire in disguise and try to find out what the big deal was. Gandalf thought it mattered, right? Maybe it did? How could these simpleton little Harfoots and Fallohides possibly be worth the attention of the Valar’s favorite wizard? Even when he could find no answer and stopped going to the Shire himself, Saruman left spies behind. Was it the herbs of the Shire, the “Halfling’s leaf” that Gandalf had made a bad habit out of smoking? The smoking, in fact, irritated Saruman greatly, yet still trying to be like Gandalf, he tried it himself and came to enjoy it. Again, in secret—everything is hush hush with Saruman. So he forever after kept his contacts in and around the Shire, and this is why Pippin and Merry would later find a stash of Longbottom Leaf in Isengard.

In the most momentous of White Council meetings, a full 90 years before the One Ring would come into the hands of Bilbo Baggins, Gandalf urged that the Council assail the fortress of Dol Guldur. After long suspicion, he had confirmed that it was Sauron, the Enemy, who dwelt there in Mirkwood. But by this time, Saruman had already learned so much of Sauron and his ring, and of the place of where Isildur had lost it near the Anduin river, that his priorities had at last shifted. No longer was Sauron a mere enemy; he was a rival, like Gandalf, and Saruman intended not to remove him but to supplant him.

Here at last his secret corruption had begun. Despite Gandalf’s urging, Saruman as the head of the Council overruled him. He advised that the Council stay its hand…

‘For I believe not,’ said he, ‘that the One will ever be found again in Middle-earth. Into Anduin it fell, and long ago, I deem, it was rolled to the Sea. There it shall lie until the end, when all this world is broken, and the deeps are removed.’

Except that he totally lied. Saruman believed that the One was still somewhere within his reach. He craved it for himself but felt that if the Enemy was driven from Dol Guldur, then the One Ring would remain unfound. He knew that the Dark Lord was seeking it again, and if he was allowed to search for it freely for a time, it might reveal itself. Saruman would just have to snatch it up first!

After this selfsame Council meeting, Saruman, irritated that Gandalf had grown silent on the matter and was smoking away on his pipe, berated the junior wizard for playing with his “toys of fire and smoke” while such weighty matters were debated. Gandalf laughed it off and defended the art of the Little People, a “merry and worthy folk,” but Saruman remained cold to him. Instead of any further reply, Gandalf “drew on his pipe and sent out a great ring of smoke with many smaller rings that followed it.” To Saruman the White, whose thoughts were preoccupied with possessing all Rings of Power, this was no insignificant gesture. He read into it, consumed by anger and hate, even though it is likely Gandalf meant nothing by it beyond gentle mockery, for had he known that the One Ring would appear again, he would not have likely dared to reveal it to Saruman. Gandalf knew he was prideful and stern, but Saruman concealed his treachery well. Yet I imagine whatever shred of friendship existed between them up till now was blown away. They were thorns in each other’s side.

Flash forward to the Quest for Erebor, of the more familiar tale of Thorin’s company and of Bilbo’s finding of the One Ring in Gollum’s cave. The White Council met again, and this time Saruman relented on Gandalf’s longstanding urge to raid Dol Guldur and drive out Sauron. But why? He had secretly learned two years prior that Sauron had finally learned of Isildur’s fate and had servants searching the Gladden Fields along the Anduin. Best not to risk his nemesis finding the One now! Time to oust the bastard! The White Council did so, driving the not-yet-fully-strong Sauron out of his hideout. Then they met again in what would be the last time twelve years later, wherein Saruman lied again. He declared that he’d found evidence that he’d been right all along, that the One Ring had indeed passed down the Anduin and out to the Sea. So that was that.

Nearly 50 years later, Saruman looked into his palantír and found himself talking directly with Sauron at last. By this point he’d already been corrupted by the very thought of possessing the One Ring himself, but now Saruman’s treason was cemented as he became a willing ally of the Enemy. Of course, to the arrogant Saruman the White, Sauron was still a rival. He was willing to play the part of subordinate to dethrone the Dark Lord in the end.

Then came the great reveal: the One Ring was revealed at last, allegedly in the Shire—of course the Shire! Things were moving quickly. The Dark Lord, now long ensconced in Mordor, sent out the Nazgûl to recover it. There was no time to lose! Saruman already had his spies in Bree and in the Southfarthing and was ever watchful for Halflings. Surprise, surprise, it was Gandalf who scared up the One Ring. How tricksy he’d been, keeping his own secret councils! All those years of suspicion and jealousy against Gandalf were reaching a boiling point; Saruman didn’t need to conceal his true designs any longer, so he used that fool Radagast to find Gandalf for him. When Gandalf did come at his summons, Saruman’s scorn was immediate, as described in “Council of Elrond.”

Gandalf observed first that Saruman now wore a ring on his finger. Presumably he had never seen such a thing before. It’s never stated within The Lord of the Rings what this portended specifically, but it’s obvious from other works that Saruman had been experimenting with crafting rings himself in imitation of his greatest rival. “Saruman the Ring-maker” he’d declared himself upon Gandalf’s arrival. Additionally, in his “Foreword to the Second Edition,” Tolkien makes it clear what would have happened if the One Ring had not been destroyed but instead used against Sauron. One development would concern Saruman:

Saruman, failing to get possession of the Ring, would in the confusion and treacheries of the time have found in Mordor the missing links in his own researches into Ring-lore, and before long he would have made a Great Ring of his own with which to challenge the self-styled Ruler of Middle-earth.

The story from here is well known to readers of The Lord of the Rings, but there are other behind-the-scenes notes that complete the picture. The first is that after Gandalf’s imprisonment on the pinnacle of Orthanc, Black Riders rode up to the gates of Isengard. Ostensibly Saruman was aiding Sauron in the finding of the Ring and he had not reported through the palantír in some time; the truth, of course, is that Saruman still hoped to claim the Ring himself and had been stalling. If he could wrench the truth from Gandalf, the Dark Lord would be less of a problem.

In one version in Unfinished Tales, the Nazgûl showed up two days after Gandalf’s escape from Orthanc. Saruman pleaded ignorance about him and the Shire, though the Black Riders later overtook Gríma Wormtongue on the road and scared the truth out of him—revealing Saruman’s falsehood. But in another version of this event, the Nazgûl reached Saruman’s doorstep while Gandalf was still trapped up top. Christopher Tolkien relates the scene:

In this account, Saruman, in fear and despair, and perceiving the full horror of service to Mordor, resolved suddenly to yield to Gandalf, and to beg for his pardon and help. Temporizing at the Gate, he admitted that he had Gandalf within, and said that he would deliver Gandalf up to them. Then Saruman hastened to the summit of Orthanc—and found Gandalf gone. Away south against the setting moon he saw a great Eagle flying towards Edoras.

OMG, I love this. With a lightning flash of insight, or a tiny glimpse of self awareness for what he’d become, Saruman nearly apologized to Gandalf! He’d just shot himself in the foot with his oldest friend (and Valinórean comrade-in-arms) and alienated the White Council—yet there at his doorstep were Sauron’s most dreaded servants, waiting expectantly, and he was left to deal with the mess he’d made alone. Saruman was up the Brandywine without a ferry, if you take my meaning. Now he hated Gandalf even more!

In his heart Saruman recognized the great power and the strange “good fortune” that went with Gandalf. But now he was left alone to deal with the Nine. His mood changed, and his pride reasserted itself in anger at Gandalf’s escape from impenetrable Isengard, and in a fury of jealousy.

The treason of Isengard was revealed by Gandalf during the Council of Elrond. In time, Saruman’s plots against Rohan—those brigands next door far beneath one of his stature—were dashed, at great cost, by Gandalf and the fired-up armies of King Théoden. Not to mention those inscrutable Ents who, according to Treebeard, Saruman used to talk with on friendly terms but had foolishly left out of his considerations. Saruman was left impotent in his tower, his plans in shambles, and his use to Mordor in question. Gandalf led Théoden and his allies up to the tower of Orthanc to speak with him.

“The Voice of Saruman,” in which we get to see the White Wizard up close in real time—his once-raven hair is now mostly white—is one of my favorite chapters. Gandalf warns his friends of the lingering power of Saruman’s tongue, for with words alone he can still persuade others. The White Messenger’s facade was bold and fair, and in a last ditch effort he grasped at the straws of alliance. He even entreated to the “high and ancient order” to which he and Gandalf both belonged, though he tried to make it proud and domineering. But Saruman eventually cracked when his words of peace failed to ensnare them. He just wanted Théoden, the Ents, and especially Gandalf to get the hell off his lawn at that point.

Saruman gave in to curses and fist-shaking, but when he tried to turn away, Gandalf forbade it. Instead Gandalf 2.0 (i.e. Gandalf the White) verbally cast him out of the White Council, observed that Saruman’s staff of office was broken (and lo, it suddenly was!), and nominally fired him from the Istari altogether. Now Saruman was just a wizard. Again, we never get to witness the early goodness of Saruman—he’d been a bad apple since before The Hobbit—but we get it secondhand through Gandalf. The rest of Saruman’s story—his final descent into misery, defeat, and persistent pride—is neatly accounted for in The Lord of the Rings.

Of further interest in Unfinished Tales is the description how, after the fall of Sauron and the coronation of Aragorn, the new king of Gondor ordered the tower of Orthanc restored to its former, pre-Saruman state. And they found treasures that the White Wizard had stolen from far and wide and stashed away. Amidst all the stolen Rohirric heirlooms, tomb-robbed trinkets, and presumably at least one Acme Ring-Making Kit™, they found a hidden door that Aragorn would not have found without Gimli’s help. Within a “steel closet” on a high shelf they found two things: An Elvish gem last seen on Middle-earth worn by Isildur himself and the very chain upon which he’d kept the One Ring! From this discovery they understood that Saruman alone had actually found Isildur’s body and destroyed it—after swiping these precious souvenirs. “Saruman in his degradation had become not a dragon but a jackdaw.” So while Gandalf had gone to and fro on his Valar-given quest to save Middle-earth in the latter days of the Third Age, Saruman been trawling the mud and waters of the Anduin with single-minded purpose.

And let us not forget that Saruman had done much more than dabble with ring-making all these years. With those trusty Aulë-inspired craftsman skills, Saruman had fashioned those defenses of Isengard which sent up “fires and foul fumes” against the Ents when they attacked. Against Helm’s Deep he sent the mysterious “fire of Orthanc,” which Tolkien kept vague, but could have been spell work or some sort of alchemy (such as the black powder cited in Jackson’s film).

Moreover, Saruman imitated his frenemy Sauron and, like Melkor before them both, created his own variety of Orcs. Or rather, by breeding them; evil can only mock, and never truly create anything new. In Morgoth’s Ring, one of the volumes in another of Tolkien’s compilations, it is understood that Saruman took an interest in the pedigree of Orcs and interbred them with Men. Figuring one needs armies to get anything done in Middle-earth, he produced “Man-orcs large and cunning, and Orc-men treacherous and vile” who do not “quail at the sun.” Whatever his disturbing breeding techniques, another thing is made viscerally clear from the words of Saruman’s own “fighting Uruk-hai” (not to be confused with the dancing Uruk-hai): He fed them “man’s-flesh.” Somehow that hyphen makes it creepier. So no, Saruman was not going to be winning the Best Istari of the Age Award.

In the extended cut of Jackson’s The Return of the King, we are treated to a woefully trimmed version of “The Voice of Saruman” that brings us a premature end to the character with a nod—and little more—to his true, literary end in the book. While I understand the reasoning behind the omission, it’s still a shame. Many fans missed him as Sharkey, his sad, Hobbit-bullying final incarnation in “The Scouring of the Shire,” but to me the real loss is simply seeing him slain too early.

Leaving Saruman bitter, alone, and alive in his tower, bereft of his power and his magical toys, Gandalf is given an important moment of his own in the book. Ever had he spoken of pity and mercy. Saruman’s ambitions had brought death and misery to so many, yet Gandalf still gave him a chance for atonement. He channeled the compassion of Manwë, who had set him on this course in the first place. He was the one Istari (that we know of) who did right by the Valar.

“Great service he could have rendered,” Gandalf said of Saruman, and he was right. Consider what Saruman knew of the Dark Lord and his movements, how he could have helped the Fellowship and all of Middle-earth with valuable insight. More tragically, consider the origin of Saruman, his original purpose, and the place he could have returned one day when their mission was accomplished. In Unfinished Tales, Tolkien says of the Istari that

though they knew whence they came the memory of the Blessed Realm was to them a vision from afar off, for which (so long as they remained true to their mission) they yearned exceedingly.

Perhaps the yearning had simply gone from him, replaced by pride. He had lusted for the One Ring, and for rulership, for far too long.

Of course, Saruman’s scenes in the films are still masterfully portrayed by Christopher Lee and at least we get to enjoy some of the dialogue from “The Voice of Saruman.” The film version of the character is, like the entire saga, a bit too concise. Where there is no time to relate even a vague history of the wizards, Ian McKellen and Christopher Lee, in their proper times, do an amazing job portraying knowledgeable immortals around which others fret, rally, or seek counsel. The nuances of the book are necessarily left behind in favor of more dramatic action. I’m certain Tolkien would never have approved of the Gandalf v. Saruman spell-staff battle, but it’s great fun to watch and, to me, serves as a chilling release for the years of (likely one-sided) enmity growing between the Grey and White Messengers.

In the 1978 animated adaptation of The Lord of the Rings (directed by Ralph Bakshi), Saruman and Isengard are visually interesting and genuinely disturbing, and he remains subtle as in the book, but we’re treated to none of the real glory of the character. Christopher Lee, however, immortalized the dark majesty of this fallen Maia and it has, at least for me, become difficult to imagine him any other way.

Even when I reread the book, returning to the real Middle-earth as Tolkien described it, Christopher Lee is there with me to say all of Saruman’s lines. His presence, like the White Wizard, dominates every scene he’s in. And why not? Lee likely read the Rings trilogy before any of Jackson’s cast or crew, and many times over. The guy met Professor Tolkien once in his now-famous little pub, The Eagle and Child, if only as a fanboy. Which is adorable, considering Christopher Lee’s meritorious career and the larger-than-life characters he’s portrayed.

And Lee knew the books, and Saruman, well, but he was a professional actor and ran with all the deviations. In one 2010 interview, he summed up Saruman condition quite well:

“Saruman’s ambition causes him to think he can take over as the Lord of the Rings, because at some stage, he feels that he is more powerful than Sauron. But it’s the biggest mistake he makes in his life, which is many thousands of years. So it’s a question of a great Wizard, one of superior intellect and brilliance, being tempted until the temptation finally overcomes him. He of course pretends to be a servant of Sauron, but Sauron sees through this. It’s a very complex character, superbly written by Tolkien…”

If they were, hypothetically, to make films of earlier Middle-earth—or more likely, when they invent virtual reality brain-chips that let us manifest the movies we’ve imagined—then Christopher Lee would also perfectly portray the younger, fairer-seeming Saruman. Consider his role as the charismatic yet creepy Lord Summerisle in the original, Cage-free The Wicker Man or any of his Draculas. He was the master of intelligent intimidation, but could turn into a monster when needed.

The sad passing of Sir Christopher Lee last month is what inspired me to write this mini tribute to the villainous wizard who Tolkien gave given greater depth than the Lord of the Rings himsef.

Quite unlike Saruman’s, Lee’s spirit has surely returned to the “far green country” in the Uttermost West.

Jeff LaSala reads and writes fantasy, in book or blog form, and is biding his time until he can read The Silmarillion to his currently-1-year-old son. Meanwhile, his wife thinks The Lord of the Rings should have had a spin-off series featuring the adventures of her favorite characters: Saruman, Boromir, Samwise, and Bill the Pony, who’d be traveling together for some reason.