“Just reasonable hopes and dreams. Doesn’t have to be science fiction.”

—Roger Sterling, “The Forecast”

After going from the made men of The Sopranos to the Mad Men of his Madison Avenue series, television showrunner Matthew Weiner might want to consider taking the plunge and next make a science fiction or horror series of his own. Weiner’s seven-season reality-based ad-men drama is so rife with references that at times it almost threatens to rocket into realms of fantastique fiction.

In the first season of the hit AMC series, creative director Don Draper (Jon Hamm) remarks about the ad agency where he works: “Sterling Cooper has more failed artists and intellectuals than the Third Reich.” One is reminded of the Norman Spinrad novel The Iron Dream, in which Adolf Hitler quits his Führer ambitions, packs his bags for America, and becomes a science fiction novelist.

Indeed, Sterling Cooper Advertising is populated with several ad men with artistic aspirations, and like Spinrad’s would-be Führer, two of them exhibit a distinct bent towards science fiction creative writing.

Early on, account executive Ken Cosgrove (Aaron Staton) is depicted as a budding author who, under a pen name, writes science fiction, such as his robot story “The Punishment of X-4.” (Lost co-creator Damon Lindelof took notice and put a tale to the title, “publishing” it on Twitter.) There is no mention of what magazine published “The Punishment of X-4,” but copywriter Peggy Olson (Elisabeth Moss) reads another of his stories, about an egg-laying girl (which Lindelof has post facto dubbed “Ova”; perhaps he will pen that one too, if he has not already), in the pulp magazine Galaxy Science Fiction.

In “Christmas Waltz,” former copywriter and pioneer civil rights activist Paul Kinsey (Michael Gladis) lobbies his old ad pal Harry Crane (Rich Sommer), who handles television accounts, to get his script read by Gene Roddenberry for a struggling new NBC series called Star Trek. His script, “The Negron Complex,” is an anti-prejudice parable about the Negron who pick Katahn for their slavemasters, the Caucasons, the twist being that the Negron are white. (With Kinsey’s turn of character as a Hare Krishna, one might guess he would write the Star Trek episode “The Way to Eden.”) Crane mentions that Star Trek is in a tough slot, up against Bewitched. The ABC Bewitched, besides being a 1960s witch coven comedy, has as its male lead Darrin Stephens, an account executive for the fictional Madison Avenue ad agency McMann and Tate.

“Ladies Room” is where references to The Twilight Zone begin (the series ran during the early Mad Men years). Kinsey shows himself to be a fan of speculative fiction, doing a Rod Serling imitation–“Submitted for your approval, one Peter Campbell…”–and threatens “I’ll kill myself” at the suggestion that CBS could cancel The Twilight Zone. Peggy, when asked by Kinsey if she watches Serling’s series, remarks that she does not care for science fiction (despite later reading Cosgrove’s Galaxy story).

Elsewhere Draper’s second wife Megan (Jessica Paré), an aspiring actress, tracks down a director lunching with Serling and, demanding a reading, makes a teary spectacle of herself at the Brentwood Country Mart (“Field Trip”).

At one stage, The Twilight Zone Companion author Marc Scott Zicree pitched Mad Men his “Walking Distance” spec script. In it, Draper spends the episode—set before the events of season four—chasing down Serling after The Twilight Zone’s cancellation, hoping to make him their new agency spokesman. (No doubt making Kinsey green with Martian envy, Zicree is also a screenwriter for various science fiction series, including a Star Trek: The Next Generation episode, “First Contact.”)

Serling’s work is elsewhere encountered when, in the aftermath of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, Draper takes his eleven-year-old son Bobby to see Planet of the Apes (“The Flood,”). Why? “Everybody likes to go to the movies when they’re sad,” explains Bobby to a black theater usher. Both father and son are slack-jawed at the apocalyptic twist and stay for the second showing. Between shows, Draper is reading a Planet of the Apes promotional tie-in newsletter, The Ape, dated “Friday, March 1, 3978” and whose headline reads BIG ROUND-UP OF HUMAN BEASTS.

In “The Better Half,” senior partner Roger Sterling (John Slattery) takes his four-year-old grandson to Planet of the Apes, just as Draper did. But after he does, Sterling’s daughter Margaret noisily objects because it gave the boy nightmares. Sterling tries to smooth things over by offering a Dr. Zaius impersonation, but Margaret insists the movie made the boy afraid of their dog because it is furry. A bewildered Sterling retorts, “Listen, I saw The Golem when I was his age. You don’t even know what scary is. I was fine.” (This may explain why Sterling, like a modern-day Phantom of the Opera, plays the organ throughout the empty offices of SCP in “Lost Horizon.”)

Meanwhile, a disdainful Megan casts doubt that Dark Shadows is “supposed to be scary?” (“Dark Shadows”). That does not stop her from rehearsing lines with her friend Julia–“Burke Devlin will never be a stranger in Collinsport”–to prepare her to audition for ABC’s gothic vampire soap, and confesses that she would kill for a break like that.

As the Ozzie and Harriet years wane and the Space Age races to the forefront of the culture, the episode “The Monolith” is dominated by 2001: A Space Odyssey, and set a year after the Stanley Kubrick film’s release. A shot of the SCP door facing Draper as he emerges from the elevator is consciously composed to evoke the Monolith discovered on the moon.

Another 2001 homage can be found in the scene in which copywriter Michael Ginsberg reads the lips of creative director Lou Avery and senior partner Jim Cutler behind the glass of a room devoted to housing a computer large enough to navigate an Apollo spacecraft to the lunar surface. Ginsberg is driven almost as mad as HAL by the presence of this IBM 360, the shape of things to come for corporate life. Given their shared animus against IBM in this episode, maybe Ginsberg and Draper should someday team up for a Macintosh commercial.

Ginsberg has had his head in the stars since his introduction. In “Far Away Places” he says he is a “full-blooded Martian” who has been displaced, and in “Field Trip” he pitches an “Invisible Boy” concept for a Mountain Dew ad.

At the house of partner Pete Campbell (Vincent Kartheiser), dinner guest Draper strips down to his undershirt to fix a kitchen sink leak, and one of the desperate housewife admirers compares him to a certain man from planet Krypton known on Earth as Superman—a movie role Hamm was once rumored to be up for (“Collaborators”). Back when Draper is relatively new to Sterling Cooper, Crane complains, “Draper? Who knows anything about that guy? No one’s ever lifted that rock. He could be Batman for all we know” (“Marriage of Figaro,” 8/2/07). Pete, in “The Milk and Honey Route,” soothes his daughter Tammy’s bee sting and dubs her “Wonder Woman.”

The Drapers’ son Bobby tells his mother Betty (January Jones) that out of all of filmland’s famous monsters–“Frankenstein, Dracula, Wolf Man, the Mummy, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon…also King Kong”–the Wolf Man is his favorite because he changes. (At first it sounds like Bobby is reading off an ad for the old Aurora monster model kit series.) Unusually attentive, Betty reminds him that Dracula turns into a bat (“Field Trip”).

Speaking of the Count, Draper says Megan’s new California house looks like “Dracula’s castle” (“Time Zones”). Viewers frequently compare Megan to The Fearless Vampire Killers actress Sharon Tate, a Benedict Canyon resident who could practically be her neighbor, and point out how two of her outfits even match those Tate once wore. This is one of several Rosemary’s Baby connections to come, as Tate was of course the wife of director Roman Polanski before the Manson family invaded their Hollywood hills home and murdered her, her unborn child, and four friends in cold blood.

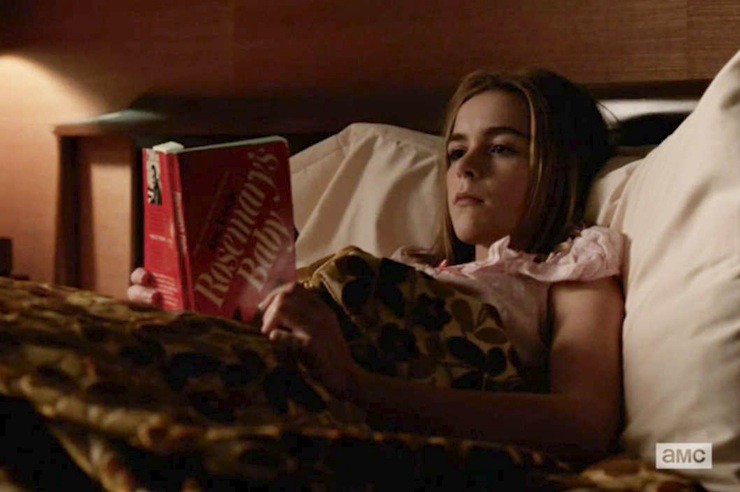

The episode “The Crash” tips its hat to the genre multiple times. Daughter Sally’s (Kiernan Shipka) bedside reading is the Ira Levin novel Rosemary’s Baby. Also, Draper’s children are watching the Prisoner episode “Free for All.” During a brainstorming session, art director Stan Rizzo quotes Poe’s poem “Annabel Lee” while pitching ideas for a Chevy ad campaign. Throughout the hour, partner Frank Gleason’s daughter Wendy casts fortunes with I Ching coins for the creative team sequestered for a working weekend, the same method Philip K. Dick used to write The Man in the High Castle.

In “The Quality of Mercy,” Rosemary’s Baby spills over from Draper’s domestic life into the office. “Really scary.” “Disturbing.” “Terrifying.” These are the words Draper, Megan, Peggy, and partner Ted Chaough (Kevin Rahm), sitting in a darkened theater, use to describe the Polanski film when the lights come up. In the bullpen, Peggy and Chaough inexplicably draft an ad campaign around the final crib scene for, of all things, St. Joseph’s Aspirin for children. Draper is “troubled by the idea of using Rosemary’s Baby” to sell baby aspirin (as well as troubled by the bloated budget for this ad concept). Could it be that lurking beneath play-it-safe Chaough’s façade is a frustrated horror director?

Pete Campbell reading Margaret Wise Brown and Clement Hurd’s Goodnight Moon to his daughter (“The Other Woman”) fits in with a larger lunar theme. Draper’s client, hotel magnate Conrad Hilton, literally wants his chain on the moon, a science fiction concept if there ever was one (“Wee Small Hours”). How one would reach a Lunar Hilton is never explained, though come the year 2001 a Pan Am spaceplane might be the ticket. Hopefully the décor will be less alienating than that of David Bowman’s hotel room.

Later, the Apollo 11 moon landing lays bare the deepening generational divide. Sally, called a budding Jane Fonda by her mother, calls the space program “a waste of money…while people go hungry down here.” Her father admonishes, “Don’t be so cynical.” In contrast, a smiling Bert Cooper (Robert Morse), the Cooper of Sterling Cooper, passes away while watching the television broadcast from his sofa. Having lived long enough to see a man walk on the moon, he dies peaceably, the office Objectivist’s last word a hearty “Bravo” (“Waterloo”).

Previously, in “The Monolith,” Sterling tries to reunite his “moonchild” daughter Margaret with the husband and son she abandoned to join a commune. While they’re stargazing together, she asks him, “I’d like to go to the moon. Don’t you want to go?,” reminding her father how he would read Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon when he was growing up.

Even the superspy genre, known for its share of science fiction elements and so much a part of the decade, gets its nods. Besides The Prisoner, Sally watches The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (“The Chrysanthemum and the Sword”). “The Phantom” alludes to James Bond by playing “You Only Live Twice” over the closing montage. Before then we hear a snippet of the soundtrack to the 1967 Casino Royale as Draper sits in a darkened theater. Around the office Lane Pryce’s male secretary John Hooker is derisively nicknamed “Moneypenny,” after M’s secretary from the Bond series. The Chevy headquarters is compared to Get Smart because of its “procession of doors” (“A Tale of Two Cities”). Typically, the always serious Draper prefers reading less super-sensational spy fiction like The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, a 1963 Cold War novel from British author John le Carré (“Tomorrowland”).

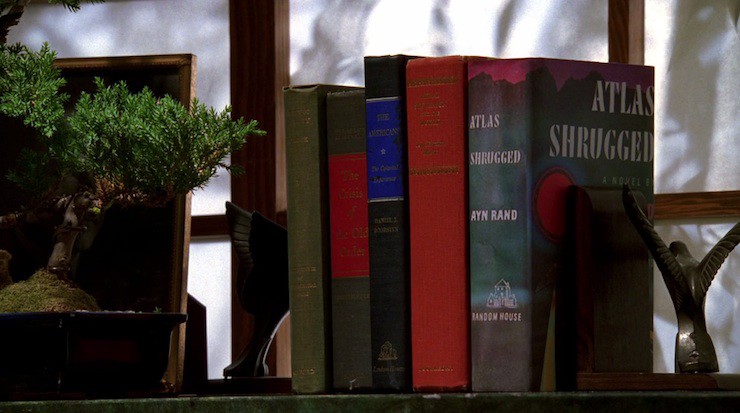

Cooper recommends to Draper the Ayn Rand novel Atlas Shrugged, set in a semi-science fiction dystopian future, hinting that he sees in him a fellow self-made John Galt (“The Hobo Code”).

Campbell reads, on his morning commute, Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 (“Lady Lazarus”).

Sterling and Draper run into their old colleague Danny Siegel at a La-La Land party and learn that he is “finally making a picture with a major studio… Alice in Wonderland” (“A Tale of Two Cities”).

It is early on established than Draper is a movie buff, and he and Lane Pryce (Jared Harris) kick off their New Year’s Eve at a cinema showing the Japanese monster movie Gammera the Invincible (“The Good News”).

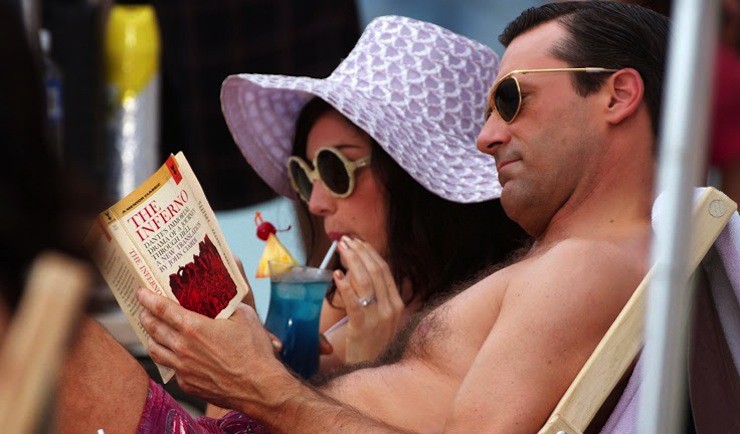

The very phrase “beach read” suggests trashy paperbacks. But Draper, even lounging around the Hawaiian sun and sand, displays his penchant for heavier fare, reading Dante Alighieri’s classic The Inferno (“The Doorway”). The epic poem, a masterpiece of horror imagery, is a gift–message?–from his married mistress Sylvia, torn up with Catholic guilt over their affair.

In the penultimate episode “The Milk and Honey Route,” motel room service brings Draper two novels, one of them The Andromeda Strain by Michael Crichton.

Sally’s palate is definitely primed for fantasy and adventure. Besides Rosemary’s Baby, she is seen reading The Twenty-One Balloons by William Pène du Bois (“The Chrysanthemum and the Sword”), The Black Cauldron by Lloyd Alexander (“Dark Shadows”), and the Nancy Drew mystery novel The Clue of the Black Keys by the pseudonymous Carolyn Keene (“The Beautiful Girls”).

Ray Bradbury’s Twice 22 is one of the books lining Megan’s shelves (“The Phantom”). The cable television series The Ray Bradbury Theater adapted several of these stories decades later (1985-1992), so if Megan were to hold out till then, she could audition.

In Draper’s memorable Kodak carousel pitch, he says of the new slide-projector, “This device isn’t a spaceship. It’s a time machine. It goes backwards, forwards. It takes us to a place where we ache to go again” (“The Wheel”).

Many episodes have titles suggesting the fantastic in one way or another (“Love Among the Ruins,” “Tomorrowland,” “The Monolith,” “Lost Horizon,” to name a few). Maybe “Tomorrowland” is a hint that some character will handle a Disney World account when it opens in 1971. “The Punishment of X-4” author Lindelof has already co-written the prequel novel Before Tomorrowland to tie in with the upcoming summer Disney film, so he might as well imagine a Mad Men scenario à la Zicree.

Astute viewers may consider this catalog just the tip of the iceberg and are welcome to add to it. Of course, pop culture references can be a cheap way to score points with superficial audiences, but for the most part, Mad Men’s are not arbitrary exercises existing only to thrill viewers with meaningless aha! moments of contextless recognition. It would make sense that advertising-types, whose jobs require them to have a finger on the pulse of the popular American consciousness, would be this culturally aware. (Though in the case of dinosaur Draper, there is a quiet desperation to his struggle to keep up with the rapidly-changing landscape of the chaotic Sixties.)

This would explain the plethora of allusions, but not why so many of them are genre-oriented. Are these references simply representative of Weiner’s tastes? Or do advertising creatives, and those in their orbit, commonly gravitate towards science fiction, horror, and similar fare?

Beyond the offices of Madison Avenue, most of the Mad Men cast have fantastical film filmographies. Hamm had a role in the Day the Earth Stood Still remake, John Slattery one in Iron Man 2, Elisabeth Moss in the ABC series Invasion, and Harris a recurring role in Fringe. That goes for some of the minor players as well. Of special relevance, Denise Crosby, Lt. Tasha Yar on Star Trek: The Next Generation, played riding instructor Gertie on two episodes, “For Those Who Think Young” and “The Benefactor.”

More recently in the world of the series, Lou Avery, in “Time & Life,” gloats how he is quitting advertising because his comic strip Scout’s Honor is being adapted by the same Japanese company behind Speed Racer, Tatsunoko Productions. Avery, the butt of jokes around the office, indignantly reminds his co-workers that the cartoon Underdog was created by Dancer Fitzgerald ad man Chet Stover. The unlikable Avery’s success may be an undeserved victory lap, but it goes to show that, despite the end of Mad Men’s seven-season run, the lives of its characters go on.

May 17th is the debut of Mad Men’s much-anticipated series finale. Given that genre giants Alfred Bester, Frederik Pohl, George A. Romero (Night of the Living Dead), Ridley Scott (Alien, Blade Runner, Prometheus), and many others began their careers in advertising–most notably Scott with his Clio Award-winning “1984,” an Orwellian anti-IBM commercial that introduced the Apple Macintosh to the world–one never knows what the future holds for these “Mad Men.”

This post is dedicated by the author to Louis A. Hanousek, agency producer at Benton & Bowles circa the Mad Men era—“It takes us to a place where we ache to go again”—and Carolyn S. Klossner, former traffic manager at SCP (in this case, Shain Colavito Pensabene)

Gilbert Colon has written for Filmfax, Cinema Retro, Crimespree, Crime Factory, New York Review of Science Fiction, and several other publications, and his interview with Body Snatchers director Abel Ferrara appeared in Invasion of the Body Snatchers: A Tribute (Stark House Press). Additionally, he interviewed Tor editor Greg Cox and Tor.com contributor Matthew R. Bradley for SF Signals. At present he is a regular contributor to Marvel University and bare•bones e-zine. Read him at Gilbert Street and send comments to [email protected].