I have always found Julius Caesar to be the most accessible of William Shakespeare’s works. The love portrayed in Romeo & Juliet? Unconvincing. Love’s Labours Lost or Midsummer? Diverting but unmemorable. The Scottish play? Actually, that one is great but I have to be in a dark mood to really enjoy it. No…to me it is Julius Caesar that proves Shakespeare’s command of language and drama. Centuries—millennia really, considering its subject matter—after its time, Julius Caesar remains a visceral and fast-paced epic.

My realization as to just why Julius Caesar remains so immediate came to me long, long after I first read it. (And in a roundabout way, that delay was its own clue.) Working at a science fiction/fantasy blog magazine like Tor.com has made me far more analytical about stories and the media they inhabit, so the more I was exposed to that analytical environment, the more I began to realize that Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar was delivering the same dramatic swings that I expect from blockbuster movies.

Upon rereading the play for this essay I was struck by how tightly plotted Julius Caesar really is. I mean…I’ve always considered it one of Shakespeare’s leaner pieces, but it’s really jaw-dropping how little extraneous material there is in the first three acts. If you really wanted to I suppose you could trim out the scene between Brutus and his wife Portia without losing anything, and you could axe the mob takedown of Cinna the Poet, as well as the opening scene with the soldiers. But you don’t really want to, as they add useful bits of context to the proceedings. The soldiers establish an anti-Caesar sentiment that extends beyond the Roman senators, letting you know that there is more motivating the main characters than craven ambition. Portia’s plea to Brutus is a stirring parallel to Calphurnia’s plea to Caesar (albeit after the fact). And Cinna the Poet’s scene is just funny. (Not intentionally, of course. Well, maybe a little bit intentionally. The plebeians do change their reason for killing him from “conspiracy” to “bad verses.”)

Perhaps more surprising than the lack of unnecessary scenes in Julius Caesar is the lack of desire for more revelation, or characterization. There’s nowhere in the story of Julius Caesar where I wish Shakespeare had revealed more about a character or setting. This is an ongoing issue I have with a lot of Shakespeare’s tragedies, perhaps most acutely with Hamlet and the absence of scenes focusing on the machinations of his mother Gertrude, the character whose choices drive the narrative.

I originally thought Julius Caesar was missing some scenes, actually, thinking that the titular character’s death comes too quickly, and that we see too few of him and explore too little of Brutus’ reasoning. If the commentary material in my Norton edition of Julius Caesar is any indication, I’m not the only person to hold these criticisms. However, upon rereading I find that those same criticisms don’t hold up within the exacting structure of the play. Brutus begins the story on the knife’s edge between loyalty and betrayal, and while it seems odd to begin with Brutus arriving at a decision, the ensuing scenes spend a great amount of time unpacking his thought process. Regarding the lack of Caesar, well, he is a larger-than-life presence in the minds of the main characters in the play, and Shakespeare very wisely translates that onto the space of the stage. A larger-than-life character would naturally push anyone else’s presence away, and so Caesar is used sparingly, and only to declare the direction in which the story will head. Caesar isn’t so much a character as an authority, both on and off the page.

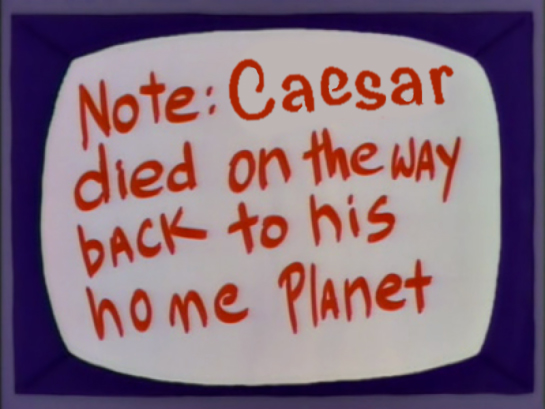

He’s kind of like Poochie in The Simpsons, now that I think of it. Too much of him spoils the balance. (Also, whenever Caesar isn’t around, people are always asking “Where’s Poochie Caesar?”)

But why would I look to Julius Caesar, or any of Shakespeare’s plays, with the notion of cutting a scene, or adding a character’s backstory? This approach is rooted in a sense of dissatisfaction with a story, but that feeling doesn’t originate with Shakespeare’s works. It’s a criteria I’m applying after the fact. And it’s an analytical view that I often take with modern visual storytelling mediums like television and movies.

The leanness of the structure and the precision of the plot of Julius Caesar remind me VERY much of modern day movie adaptations. Shakespeare drew from a variety of historical accounts of the characters in the play, from Julius Caesar himself to Marc Antony, to Brutus, and so on, and distilled those events and motivations down to their core. For example, Shakespeare may have learned loads and loads about the unequal economic state of the entire Roman Republic, but that knowledge appears only in a line where the people are promised 75 drachmas each upon Caesar’s death, and that “fact” is only there to give Marc Antony’s epic Forum speech a realistic bent in comparison to Brutus’ more philosophical reasoning. The judicious pruning of detail is done in the service of the story that Shakespeare wants to tell—one of tyranny and rebellion, of politics and brotherhood—and the actions and personas of the real-life figures in Julius Caesar inform that story instead of protesting against it.

This kind of approach did not originate with Shakespeare—mankind’s oldest fables are probably just The Best Bits Of Someone’s Life, really—but Julius Caesar presents a refinement of that approach that I see play out repeatedly in the epics of our time.

You can see the same machinery working in pretty much any biopic. The boundaries are pre-determined by the format (in Shakespeare’s case: five acts, in Hollywood’s case: two hours), so any movie you make about a historical figure gets planed down to its most basic elements in order to fit within those boundaries. The scenes in Mark Zuckerberg biopic The Social Network focus on a succession of stunted social interactions as a way of explaining the motivation behind the creation of Facebook. Zuckerberg’s longtime girlfriend, his parents, his philanthropy, and any other projects he’s working on besides Facebook are ignored. Larger than life figures like those depicted in Gandhi or Lincoln build their stories around events that inspire or push the subjects to greatness. Musicians tend to get biopics that feature the tragedies and majesties that fuel their music (Walk the Line, Amadeus, Nowhere Boy). All of these adaptations, Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar included, are highly selective about their subjects.

The approach that Caesar touts goes further than mere selection, though. It selects precise actions and motivations from the real lives of its characters in order to create something larger than the sum of its parts. How many moments of truth does a life hold? A handful at most? What of the lives in relation to that first life? These moments of truth are all Shakespeare needs to craft Julius Caesar. We as readers move moment to moment, leaving the quiet interludes and finer details unremarked, and the succession of such weighty scenes creates an epic, a turning point in history itself.

You can see this in the play itself as it progresses towards Caesar’s death.

- Act 1, Scene 1: A couple of soldiers get fed up with Caesar’s glory-hogging and war-mongering and start tearing down celebratory signals of his return.

- Act 1, Scene 2: We meet all the central players: Caesar, Brutus, Cassius, and Antony; Caesar makes a show of denying a crown offered by Antony; Brutus resolves that Caesar is going too far; Cassius talks a lot. Like, a lot. (I love him for it, though.)

- Act 1, Scene 3: Cassius rallies more conspirators.

We’re only one act in and already we’ve met Caesar and are planning his overthrow. You’d expect things to slow down in Act 2, but they don’t:

- Act 2, Scene 1: Brutus agrees to lead the conspiracy, the heavens themselves begin to protest at the coming events.

- Act 2, Scene 2: Calphurnia has a dream that Caesar dies and the heavens and even the omens of his priests agree with her. Caesar doesn’t listen.

- Act 2, Scene 3 and 4: As Calphurnia tries to stop Caesar, Portia tries to stop Brutus. Brutus doesn’t listen. (Also there’s a random guy who wants to give Caesar a letter warning of the conspiracy.)

You would expect some more back and forth about the pros and cons of killing Caesar, and while you get that in some sense (Caesar’s pride in the face of all warnings is particularly damning) Shakespeare mostly uses Act 2 to ratchet up the tension bit after bit after bit, offering an escalation of elements until it seems as if Caesar is pushing against every fiber of the world. It builds a tension that you just can’t look away from. By the end of Act 2 you know Caesar is doomed and you just want to yell at him to stay home, doesn’t he see the whelping lions in the streets? Shit is weird, would-be First Emperor of Rome! Take a day off!

All of the scenes build the plot and progress the story, although they also brilliantly flesh out the main characters while doing so. At this point in the story I’d be a little worried that the tension is going to be strung along for too long, but nope.

- Act 3, Scene 1: Caesar is killed.

- Act 3, Scene 2: Brutus explains why they killed Caesar, Antony outmaneuvers him. All the conspirators realize how screwed they are and cheese it right on out of town.

- (Act 3, Scene 3: A poet dies, hilariously.)

The death of Caesar and the speeches in the Forum are just…stunning. All of the bolt-tightening tension of Acts 1 and 2 pay off here and it’s such a perfectly encapsulated moment of truth, more than that, it’s a perfectly encapsulated moment in history. Caesar’s death was a turning point in Roman history and thus it is the turning point in the play itself. From here on in Julius Caesar it’s a downhill race into chaos. Seriously, you could encapsulate Acts 4 and 5 as “Brutus: We are screwed and I am so sorry.” and “Antony: You are screwed and you are so sorry.”

It’s not just modern day biopics that echo this structure, either. Pretty much any summer blockbuster sci-fi/fantasy movie in the 21st century follows this structure. Superhero movies do it automatically. Batman Begins, Man of Steel, Amazing Spider-Man, X-Men: Whatever, Avengers, Guardians of the Galaxy…if there’s not that rush towards chaos at the end then it doesn’t really feel like a superhero movie. Modern fantasy novels tend to embody this structure, as well. Three of the bestselling fantasy series—The Lord of the Rings, A Song of Ice and Fire/Game of Thrones, and The Wheel of Time—echo this structure.

While Julius Caesar acts as a template in regards to relentless pace and economy of storytelling for, at minimum, modern day biopics, fantasy novels, and summer action blockbusters, the similarities aren’t exact. How could they be? There are centuries of storytelling in between Shakespeare’s work and today. Perhaps the largest difference between then and now is the seeming transposition of tragedy. In Julius Caesar the tragedy is the central anchor of the entire story. Everyone’s actions revolve around it. In the above-mentioned superhero films the tragedy is…well, sidelined.

Sure, Peter’s Uncle Ben dies and Batman loses his parents and Tony Stark builds thing in a cave with a box of scraps, but the stories that we see are inspired by those tragedies more than they are in reaction to them. And ultimately, all of these stories are about the heroes’ triumph over tragedy. If Shakespeare had used tragedy in the same manner as a superhero film, Brutus would survive at Philippi and kill Antony by making him eat a hot coal or something else vaguely-but-not-at-all ironic. Then in the post-credits scene it would turn out that Caesar was STILL ALIVE thanks to fearsome bionic technology, and now he is going to make the Roman Republic HIS TO RULE! Brutus you sunuva…you were right the whole time! Good job sticking to your guns! (Because in this version he has guns for arms.)

Would modern day blockbusters—superhero films in particular—shed some of their same-ness if they restored tragedy as the central pivot of the story? I don’t know, but I’d like to see one of them try. Avengers almost went there with Coulson’s death, The Dark Knight almost goes there with Rachel’s death, Man of Steel almost goes there with Jonathan Kent’s moronic tornado death. “Almost” is the key word here. Caesar is the central authority in Shakespeare’s play, but none of the above-mentioned characters are at all central to their respective stories. Perhaps these films could borrow a little more from the tragedy of Julius Caesar, and a little less from the structure of Caesar, but maybe they already are and I’m just not seeing it. (You could make an argument for The Hunger Games films here, I bet.)

Writing about television, books, and sci-fi/fantasy media on Tor.com is what made the parallels between Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar and modern day blockbuster movies apparent to me, but recognizing their similarities isn’t enough. I want the stories created today to be as great as those created centuries ago. Julius Caesar is a thrilling, dense work that makes an event as grand as the beginning of the Roman Empire into a deeply personal experience. It’s one of those rare stories that stayed with me for days after I first read it, and I know it will stay with me until my mind grows cold. Would that I could have that experience every summer, when the latest superhero comes tromping onto the screen. Or every fall, when the next great doorstopper of a fantasy novel bends the shelves.

Considering how annual the occurrence of these mediums is, I am not alone in this desire. We are all trying to recapture and expand upon the timeless greatness inherent in plays like Julius Caesar. If not this movie, then perhaps the next movie we watch, or make, will be the one. If not this book, then perhaps the next book we read or write will be the one.

Certainly, we will not always succeed. Surely not every story can be as great as William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. The play becomes the figure it depicts, bestriding the narrow world like a Colossus and we petty storytellers walk under its huge legs and peep about.

But what a guiding light, eh?

Chris Lough is the production manager for Tor.com and writes about superhero media for the site.