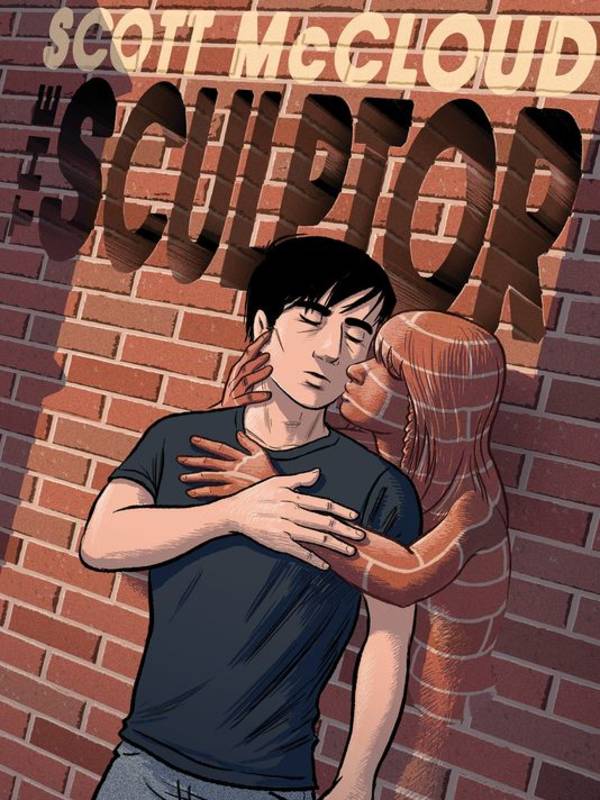

David Smith has two hundred days to live. More specifically, he has two hundred days to create a work of art that will embody his memories and his dreams, one that will stand in his place once he’s gone. In a city with hundreds of other David Smiths listed in the phone book, David’s desire to be remembered will be hard-won at best. Then he meets Meg, and his new-found superpower to bend any material to his will seems like the least of his worries.

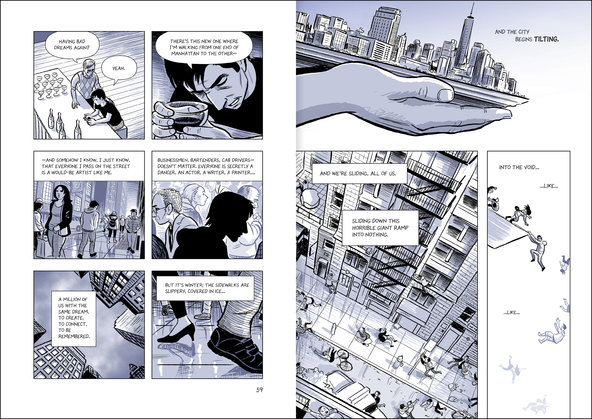

Scott McCloud—best known for his seminal work, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art—combines Faustian myth with brilliant visual storytelling in his new graphic novel The Sculptor. Using panel after panel of towering cityscapes and crowds of anonymous faces, McCloud sets a stage that will be familiar to many readers, especially those with creative ambitions.

At the novel’s opening, David is at the end of his proverbial rope. He’s broke and all but homeless, has one friend and no remaining family—but all of that would be alright if he could just make one good work of art. In a lonely bar on his twenty-sixth birthday, he makes a deal so he can do just that. In Faustian-inspired fashion, a spectre in the guise of his favorite uncle offers David the artistic immortality that he desires, in exchange for his life. David accepts (of course)—and the result is that shaping stone no longer takes days, but seconds, and his creative energy has never been stronger. At first, his pending death doesn’t seem to matter. But even before he starts to realize what he’s given up, David has to confront that creating amazing art doesn’t always yield recognition, and it certainly doesn’t mean he’ll be able to pay his remaining few months of rent.

David finds an unlikely friend in a woman named Meg. Optimistic and kind to the point of foolhardiness, Meg is as much an aspiring artist—in this case, an actress—as David. By bringing him into her life and sharing her own doubts and hidden pain, Meg forces David to question his decision to give up his life. She forces him, in fact, to question a great many of his decisions and assumptions.

Strangely enough, I read The Sculptor concurrently with Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet (available for free here). In many ways, these artist manuals compliment one another (they both emphasize self-love, for one; they both made me cry, for another), but The Sculptor makes one major departure from its predecessor. Where Rilke implored his fellow poets to cultivate their solitude, McCloud’s focus is not on the artist, but on the people around them. The novel begins with David alone, but with the turning of each page and the unfolding of each panel, his world expands. His relationship with Meg is not only the story’s emotional core in terms of romantic passion, but because his development as an artist depends on him reaching out, rather than sinking in.

In one of the novel’s earlier passages, David describes a dream he had about a crowd full of artists falling from a tilting city. It’s a jarring image, one that has stayed with me since I encountered it for the first time. The image also perfectly embodies the strains of fear and inevitability that are threaded throughout the story. Though McCloud introduces this crowd of “other” artists early in the novel, it’s not until later that he reveals their importance. In The Sculptor, everyone has a story. McCloud gives his characters—Meg in particular, of course, but even side characters featured for less than a page—lives and dimensions beyond their relationships with the protagonist. David’s journey is as much about appreciating the complex inner lives of the people around him as it is about himself as a creator. Besides providing a more vivid and emotionally authentic story, these themes help The Sculptor to do what so much media has recently tried and failed to do—it subverts the manic pixie dream girl trope. Meg’s character development flies in the face of what you’d expect from a story about a male artist falling in love. As Meg tells David, “the sun’s gonna rise and set on me too, buddy.”

Alongside its melancholy ruminations (even the ink is blue), The Sculptor holds so many moments of genuine pleasure and discovery. The art—both McCloud’s and David’s—is fantastic and thoughtful, and blends with the story in a way that I can only describe as graceful. McCloud is as much a master of his form as Rilke, and his advice to artists as complex and moving. It will resonate with anyone who has ever thought that they had a story to tell.

The Sculptor is available February 3rd from First Second.

Read an excerpt here on Tor.com

Emily Nordling is a writer and reader living in Chicago, IL. She thrives primarily on tea, books, and social justice.