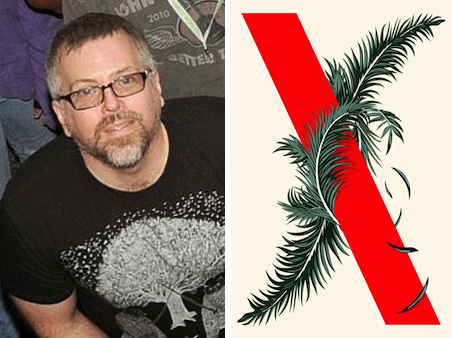

Since the first and second Tor.com interviews with Jeff VanderMeer, his Southern Reach Trilogy, which concluded with Acceptance in August, has appeared on several Best Of lists this year. Meanwhile, an omnibus edition of the entire trilogy has been released in hardcover and VanderMeer, on tour again in support of the books, has been interviewed many times.

For this third and final interview about the Southern Reach Trilogy, then, we talked more about the overarching themes of the trilogy, the places it was written from and about, and what’s next—for VanderMeer and for us.

Brian Slattery: You mentioned to me that “readers colonized by the first two novels look askance to some degree at any answers in Acceptance. In other words, some readers have been conditioned to be suspicious of the veracity of anything they’re told or a character discovers or surmises. Given the themes of the novels, I can’t help but be happy about this development and hope it carries over into real life.”

Colonization is an interesting and delicious word choice. I’d like you to flesh out the subject a little bit: Who or what is the active colonizer? If the book, how do you see it as an active agent of colonization? And regarding the part about it carrying over into real life, do you mean that you hope readers become more skeptical in general or about something more specific pertaining to the themes of the book?

Jeff VanderMeer: I know that the books were all on some level massively influenced by my subconscious and there are things in all three that I left in because I knew they were right—there was a resonance—but I couldn’t always identify why until later in the process. And then added to that are the things I deliberately layered into the subtext. First, there’s the way in which we no longer seem to live in the world of facts but in separate pocket universes, and the ways in which information overwhelms us. Information has been weaponized. It almost doesn’t have to be misinformation or disinformation. Just the sheer glut of what is coming at us, that we have to sort through, is a kind of violence perpetrated upon us. It condemns us to a series of tactical battles, many of which are holding actions in which redoubts of Fact try not to succumb to extraneous information or propaganda. In the midst of this most people are buffeted and become to some degree rudderless, even when they think they’re holding the tiller and guiding the boat somewhere.

So this is the thread that in Authority and Acceptance follows the degradation of our modern systems of thought, against which human beings can revolt and scheme but which in the process of re-acting will still wind up being contaminated … colonized. It’s not by chance that Control has to wade through documents in much the same way as the expedition in Annihilation has to wade through journals.

And then there is the thread about the natural world. I think a review in the Brooklyn Rail came closest to capturing what I was going for: Area X is to human beings as human beings are to the rest of the animal kingdom. An inexplicable force that colonizes the world and whose reasoning seems inconsistent, irrational, and ultimately unknowable.

The colonizing of the reader that I hope is most potent, though, comes from the landscape, the setting. When I describe Area X in Acceptance in intense specific details I am doing that because I love North Florida’s wilderness and even as I love it I have to accept that if things continue the way they’re going that it may not exist by the time I reach 70 or 80 years of age. It is my attempt to capture the world I love before it’s gone. What could be more compelling than that, if that love colonizes the reader? If the reader succumbs to that? I am saying, using the backdrop: this is what we’re losing, what we’ve almost lost. Why would any sane person want to contribute to that? I don’t like didactic novels. I don’t even like putting the ideas I believe in in the mouths and minds of the most sympathetic characters in the novels I write. I’m suspicious of agitprop. So this is my way of going about it.

BS: You mentioned to me that “an answer is something you expect from a mathematical equation. But life’s a lot messier than that, and people are a lot less rational than we believe. So, how can there be precise answers when we are not ourselves precise? And becoming less so as the idea of there being a single fact-based universe is, for human beings, fading into the distance.”

What do you think this means for how we tell speculative stories now? What kinds of speculative fiction do you see not working as well any more? And kinds do you see emerging on the horizon?

JV: Personally, I don’t think this is a worldview that necessarily permeates speculative fiction. A fair amount of speculative fiction has succumbed to the lie that people are rational and that the world runs on logic—and the part that has succumbed to this simplification is also the part that’s been colonized by too many commercial tropes. I’m reading The Kills by Richard House right now. It’s an ambitious spy thriller that reminds me in places of 2666 as well. The undercurrent of the absurd and irrational that helps power this novel is a thousand times more recognizable as a marker of our times than the last ten science fiction novels I’ve read. This doesn’t mean non-speculative fiction is any better suited or that I haven’t read a lot of SF I’ve liked recently, too. But that I don’t find a compelling argument for why spec fic is the standard bearer in this department.

BS: What do you think of the Uncivilization movement?

JV: I’m fairly skeptical of movements, organizations, and institutions in general. I would like to think that Dark Mountain has value, but I’m wary of any romanticizing of our situation. I’m wary of anything that says we need to somehow get in touch with our more primitive selves. The fact is, our Western relationship to nature (I can’t speak for any other) has been problematic for much longer than the start of the Industrial Revolution. There’s a fundamental drive for expansion that is almost pathological. Something in the coordinates in our brains that, especially in groups, drives us to run errant and run odd. I suppose the practical side of me thinks that not many people at all will join Dark Mountain anyway so it’ll have no real effect. And then on other days when I see a huge battle-sized SUV idling in the parking lot of the Starbucks I have the urge to run up to the driver’s side window and scream “this vehicle shouldn’t even be fucking legal, you asshole.” Before I get in my almost-as-bad Toyota Corolla and drive away and am calmed by the faint hope that if the 50 militaries and 75 companies that produce most of the world’s global warming would cut emissions drastically we might get out of this alive. And then think “Except we’re most probably all walking ghosts who don’t know we’re dead yet.” Maybe this doesn’t sound particularly cheery, but I’d rather we faced this thing head-on and realistically even if it seems pessimistic. There’s a kind of comfort in that.

BS: You mentioned in a question on Goodreads about the collapse of the anthropocene “the question of being able to see our environment with a fresh eye—so that we no longer think in terms of being stewards or despoilers but some other philosophy altogether. And this in the context, too, of not bringing with us the old ‘culture creatures’ as Schama puts it in his book Landscape and Memory. That we might see with clear vision but also perhaps with a hint of awe just how thoroughly we live on an alien planet that is full of wonders we’re only now beginning to understand. And of which we are at times the most mundane.”

What is the place for human culture as we understand it in this vision? Not simply in helping us reach this point, but after that point is reached? I admit that if you suggest that we don’t need to write or play any more music once we’ve adapted, I will be sad.

JV: No banjo ever added to climate change as far as I’m aware.… One start is simply better integration with our environment, and that means the rude massive jolt of many more trees, more forests, and our presence minimized within the world. It means ripping up all the pavement and concrete. It means going solar fast. It means letting the natural world destroy part of our made-up pre-fab world. It does mean abandoning our cars. It means disbanding harmful corporations.

It doesn’t necessarily mean huddling around a fire with a rat crackling on a stick and living in caves. But think of all the useless, needless crap in our lives and the ways in which we somehow wonder, for example, how anyone got anything done without smart phones—well, you know, it actually happened. I was there. Things like that. Because it’s not just about global warming—it’s about pollution in general and our attitude toward animals and a whole raft of other issues. Can you imagine advanced aliens looking down on our little pile of mud. “Wow—great music and that 2666 isn’t bad … but what the hell is all that other stuff going on?! Look—just plastic bottles of water and a build-up of toxic kitty litter almost killed them off. How stupid is that?”

BS: Do you think we can adapt?

JV: No. I think it’s going to be forced on us, and it’s going to be ugly. And if we come out the other end, it’s not to going to matter if we survive by the skin of our teeth if our attitudes haven’t changed. We’re living in the middle of a miraculous organic machine, the moving parts of which we don’t understand, but we still persist in destroying a lot of parts of that machinery. “Oh—what was this switch? Probably don’t need that. Let’s junk that. Oh, wait—that was connected to this other thing we need? Well, too late. Oh well.” Yet I remain essentially a long-term optimist—as in a 50-billion-year optimist. Something’ll be growing here even if we aren’t. I know it seems like a contradiction, but I believe in nature. (I believe in a lot of individual human beings, too, but I hope that goes without saying.)

BS: Now let’s circle back, to one of the places where it began: the St. Mark’s Wildlife Refuge (where I still very much want to go one of these days). As you wrote, from Annihilation to Authority to Acceptance, did you find yourself revisiting the place, or did you eventually end up in a sort of St. Mark’s Wildlife Refuge of the mind?

JV: It’s more that some elements of another place I’ve grown to love—the coast of Northern California—began to permeate certain sections, so at times I was seeing double. But the tactile certainty of St. Mark’s is still there, although as you suggest it is continued metaphorically. But I did, with my wife Ann, take a trip to the Panhandle in the winter of 2013, as I was finishing Acceptance. I wanted to remember specific details I might otherwise have been tempted to fudge. There’s a scene in Acceptance where Control and Ghost Bird cross over to an island by boat. Every detail of that passage was collected during that journey down the coast in the winter. I had to have a continuing anchor to make sure the narrative didn’t get too abstract.

BS: Now that it’s been a few months, what (if anything) do you miss about being around and writing the characters in the trilogy?

JV: I miss the former director. I miss her a lot. I became very attached to her and came to see her actions as essentially heroic. Heroes aren’t always people who save others in the normal sense. Sometimes they’re people who keep trying even when things seem impossible. And I wonder sometimes where Grace and Ghost Bird are. But I don’t miss the biologist. I know she’s doing just fine.

BS: And finally, what’s next?

JV: I’m working on a novel about an intelligent weapon, discovered by a scavenger-woman in the matted fur of a giant psychotic bear that can fly.

Brian Slattery is an editor, writer, and musician. His first three books were published by Tor.