It is claimed Albert Einstein said that if bees disappear from the earth, mankind has four years left. When bee-vanishings of unprecedented scale hit the United States, Orvo, a Finnish beekeeper, knows all too well where it will lead. And when he sees the queen dead in his hives one day, it’s clear the epidemic has spread to Europe, and the world is coming to an end.

Orvo’s special knowledge of bees just may enable him to glimpse a solution to catastrophe: he takes a desperate step onto a path where only he and the bees know the way but it propels him into conflict with his estranged, but much-loved son, a committed animal activist. A magical plunge into the myth of death and immortality, this is a tale of human blindness in the face of devastation—and the inevitable.

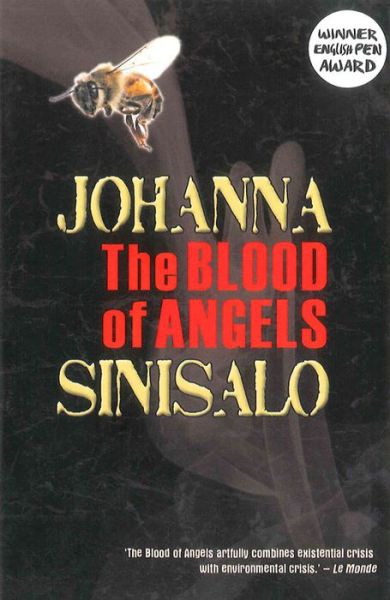

From Johanna Sinisalo, the award-winning author of Troll, comes another haunting novel of eco-speculation, The Blood of Angels. Translated from the Finnish by Lola Rogers, The Blood of Angels is available now from Peter Owen!

DAY ZERO

The queen is dead.

She’s lying in the entrance hole, delicate, fragile, her limbs curled up against her body.

I would recognize it as the queen just by the elongated lower body and clearly larger size compared with the worker bees, but there is also a little spot of colour on her back—I marked this female with yellow last year when I placed her in the nest.

Much too young to die.

And why had she left the nest to begin with?

I squeeze a puff from the smoker into the hive, but the bees don’t come crawling out. They should be languid, of course, fat and heavy with honey to protect from this imagined forest fire, but there’s no movement at all at the entrance.

My heart is racing now. I put down the smoker and pry the roof off the nest with a hive tool. I put the roof on the ground and start lifting the honey combs out of the box one by one and stacking them on top of it.

The workers are gone.

Every one of them.

Just a few individual hatchlings crawling over the honeycombs looking befuddled, baffled by the sudden flood of light from above.

A tight fist closes at the pit of my stomach.

It can’t be. Not here, too.

I carefully pick up the queen and put her on the palm of my glove.

There’s no reason this particular nest should need a fresh queen. Sometimes the old queen is killed when a colony ends a generation, but even if there were a new administration it wouldn’t cause the bees to desert the nest.

Are they swarming? No. I’m sure I would have noticed it if the colony felt crowded or larvae had appeared in the queen’s combs. And even if the old queen had evacuated the nest with her escorts to make way for a new queen the nest would have been more or less the same, although the group would be a little sparser and younger at first. It’s also an unusual time of year to swarm; that usually happens in early or mid-spring.

But I look carefully at the surrounding trees because I certainly don’t want this to be what I fear it to be. In spite of my hope I don’t see any dark splotch, its blurred edges abuzz, in the branches or treetops.

But they’ve gone somewhere. Vanished as if into thin air. Into nonexistence.

The queen lies lightly on my gloved hand like a flake of ash, but she feels so heavy that my wrist trembles. I take a breath, take the queen catcher out of my overall pocket and put the female inside. I drop the clip back into my pocket. Maybe I should send it to be analysed.

I don’t dare to go to look at the other hives. Not now.

I’ll do it tomorrow.

I have to take the rest of the frames out of this nest and put them in the centrifuge now anyway. Whatever it was that happened, the honey still has to be collected.

The sun is low over the meadow, soon it will be just an orange glow behind the tattered edge of the wall of spruce trees.

Back at the house I turn on the console with the remote. I hadn’t wanted one of those voice-activated consoles with a monitor that covers half the wall; the screen on the wall over the table, smaller than the window, was big enough. There used to be a ryijy rug in that spot on the wall. The console is one Ari bought for me against my will, supposedly as a Christmas gift, me a grown man who supports himself, as if I were a spoiled child. A gift has to be something new, something expensive and useless, to keep your offspring content. I guess there was no way to avoid it, although it looks oversized in a little two-room cottage. Now that I’ve finally got used to it they tell me I ought to get a new one. Eero gave my console a nickname to tease me. He calls it my Lada, and sends me links to new fully interactive, high-definition models with the highest available data speeds. As if I needed the most advanced technology possible to watch the news, read my email, do my banking, order groceries twice a week and watch an occasional movie. Oh well—I do read Eero’s blog on the console once in a while. It’s almost like chatting with my son without needlessly disturbing him.

He’s one to talk—Eero wouldn’t have a wall console if you gave it to him for free. He carries a phone in his shirt pocket, does his work with a real computer with just the software he needs and doesn’t even have an entertainment terminal. Even when he visits here he doesn’t so much as glance at my console. He’d rather sit in the corner with his phone in his hand, wandering around the web looking at television shows and movies the way I would read a book.

It just so happens that the first message on my list is from Eero. Just a routine message to let me know he’s still alive, some scattered comments about how he is, but his messages always warm me.

There’s some news, too. He has a paying customer now, a temporary gig sprucing up the customer feedback page for an electric-bicycle company. He’ll be able to pay his rent for several months now.

I’m proud and embarrassed at the same time. I agreed to let him move to Tampere ‘on a trial basis’ on the condition that he kept his grades up and paid his own expenses. I had thought that a seventeenyear-old boy would come back to Daddy on the first milk train even if it meant an hour’s commute to school. But no, Eero not only raised his grades—his prospects for the graduate-entrance exams in the spring are looking frighteningly good—he also succeeded in getting a job. At first he worked as a dishwasher and janitor at a vegetarian restaurant owned by an acquaintance, but now his contacts and capability in the world of the free net have started to provide employment. I send a short reply to his message. I can’t resist mentioning that school is starting again soon and it has to come first.

Another message is from a courier company informing me that the new bee suit I ordered from a bee-keeping supplier has arrived and has to be picked up at the service point in town. They used to call it the post office. It costs extra to get them to bring it all the way to my house, but picking it up isn’t any particular trouble. It gives me an errand to do someplace other than work and is, in fact, a rare opportunity to run into people going about their ordinary business.

There’s a pitch-thick, stone-cold irony in the fact that my new overalls arrived today of all days; a lot of joy it’s going to give me if…

Hush. I had to order it, I really did. In spite of washings my old suit has become so saturated with honey that the bees are going to start to think my smoker and I are just a mobile, eighty-kilogram hunk of honey that needs to be brought safely out of fire danger.

A click of the remote and the news appears on the monitor. The top story is from North America, as it has been for a couple of months. The situation, already critical for a long time, has once again exceeded the most pessimistic predictions.

Twenty years ago, when the first wave of Colony Collapse Disorder arrived, I read reports about it with more worry than I’d felt since the days of the Cold War in the 1960s. Back then was a little boy lying awake in bed waiting for a nuclear war to start. Now I can hear the clock ticking down to Judgement Day again.

I mentioned the disappearance of the bees to a random acquaintance back in 2006. I brought the subject up mostly to ease my own worried mind.

The acquaintance said it really was awful, but he supposed he’d just have to learn to live without honey.

Honey.

Food riots are continuing all over the USA and now they’re spreading to Canada, too. The US government has once again limited the distribution of certain food products and in some states—mostly those that don’t have their own source of potatoes—they’re serving ‘vitamin ketchup’ along with the cornmeal mush and pasta in the schools because symptoms of malnutrition are starting to appear. Of course, it’s nothing like real ketchup because there aren’t any tomatoes.

The price of food has quadrupled in a very short time. Not long ago the American middle class was barely keeping up with the cost of mortgages, petrol, healthcare and tuition. Now they can’t afford food any more.

The world’s former leading grain exporter is reserving its crops to feed its own people, and the trade balance has plummeted. International credit is in shreds. With the rise in food prices, inflation is rampant. The EU banks and International Monetary Fund are making a joint effort to create at least some semblance of a buffer so that the US crisis doesn’t completely collapse the world economy, which is already in turmoil. The dollar is on artificial respiration while we wait for the situation to ‘return to normal’.

California’s complete collapse is relegated to the second news item because it’s already old news, but that’s where the situation is worst.

Groups of refugees are invading the neighbouring states of Oregon, Arizona and Nevada as well as Mexico. Those south of the US–Mexico border are finally glad to have the wall the Americans once built, with its barbed wire and guard towers. It’s coming in handy now that hungry, desperate fruit-growers are trying to get into Mexico to find any work they can get as janitors, pool boys, nannies and drug mules.

They’re looking for someone to blame. The newsreader says that in 2004 the George W. Bush administration—making use of the media overload covering the approaching election and the war in Iraq—raised the ‘tolerances’ for certain pesticides. Since the media was too busy to take up the subject, the public was unaware of it, including bee-keepers.

Fruit-growers, however, must have known that their pesticides had a new kick and rubbed their hands in glee. But no one really knows if those pesticides are the cause of the disappearance of the bees or if it’s something completely unrelated.

They have to find someone to blame. Someone has to pay. With the trees no longer bearing any fruit there’s nothing left to live on.

A group of California orchardists is surrounding the White House now, furious and determined. ‘Who killed the country?’ is one of the most popular slogans on the demonstrators’ signs. I notice another one: ‘The CCCP didn’t put us on our knees, the CCC did.’ There seems to be some kind of riot outside the frame of the picture because I can hear noises that couldn’t be anything but gunshots.

Next is a documentary clip from California.

Before the CCC phenomenon almonds were California’s single most valuable export crop, more valuable even than Napa Valley wines, says a soft workmanlike voice, and a picture of February’s blooming almond trees comes on the screen. The trees stretch for kilometres in every direction. Some sixty million trees in all, in even, orderly rows. Beautiful and sterile.

The picture shifts to China. The unregulated use of pesticides killed all the bees in Northern Szechuan province in the 1980s. It was an important fruit-producing region, and the livelihoods of the local people were entirely reliant upon what their trees produced.

Old footage comes on the screen—Chinese families right down to the grandparents climbing in the trees touching the blossoms with fluffy tufts on the ends of bamboo poles. They had, with great difficulty, gathered the pollen of the male flowers into basins, and now the screen showed them balancing awkwardly on ladders distributing the pollen to the female flowers. I watched their futile efforts with fascination. One single bee colony can pollinate three million flowers a day.

At the time they could hold out the hope of hand-pollination because labour was relatively cheap in Szechuan and it was only in that one area, the narrator explains. But now CCC has finally struck the USA and no amount of resources is enough to hand-pollinate all the fruit trees in California. Even if workers could be found it would cost billions in rapidly declining dollars. There’s a rumour that the USA plans to reform their criminal sentencing to require community service in fruit-growing regions. Volunteers are being organized and trained in hand-pollination.

There are a few odd pollinating insects in California’s almond orchards—the occasional fly or bumble-bee—but most of the almond harvest has been lost.

The correspondent restates the event: Colony Collapse Catastrophe, the Triple-C, BeeGone, hive desertion—more complete, wide spread and destructive than any bee disappearance to date.

In the first half of the 2000s the abbreviation for the wave of hive desertions was CCD, Colony Collapse Disorder. They never found an air-tight, unequivocal explanation for it, just numerous theories.

No one’s talking about a disorder any more. They talk about a catastrophe.

Almonds.

I remember seven years ago, when Eero spent a whole week at a summer camp in Lapland. I had some time on my hands. On a momentary whim I took a cheap f light to Malaga and rented a bicycle. I went on a leisurely ride around Andalusia and Granada, stayed in little village hostels, even took a side trip to the Alpujarras, along the mountain range. I stopped to wonder at the trees with their pale-green, hairy, tapering fruits the size of birds’ eggs. Someone told me they were almonds. Inside the fruits were stones like in a plum, and inside the stones were the edible, delicious seeds.

The flanks of those Alpujarras foothills were filled with gnarled old almond trees. There were scores of them, and the fences around the orchards were invariably hung with glum, swaying, hand-painted signs that read ‘Se Vende’. For Sale. The lifeblood of the Spanish highlands from time immemorial hadn’t been profitable for some time. But now I can imagine the hordes of developers driving from village to village in their black SUVs offering rustling euros for those unproductive pieces of land. Toothless old men and stooped women finally owning something somebody wants, something sought-after, valuable.

And over it all, cheerful and diligent, waving her invisible baton, dances sister bee.

Before the Mediterranean countries got their production to rise, an almond for the Christmas pudding might be the single most expensive purchase for a holiday meal. And just as I’m thinking of a Christmas table I realize that the association with Christmas hasn’t just come from the recesses of my mind. I can see something out of the corner of my eye, through the window. A flash of blue light over the Hopevale facility, harsh flashes like Christmas lights gone mad in the middle of an August evening. And then I hear distant noises, a shout, and I realize that the light is coming from the roof of an emergency vehicle.

EERO THE ANIMAL’S BLOG

PONDERINGS ON OUR RELATIONSHIP WITH ANIMALS

SHOUTING TO THE POLICE FOR HELP

Once more my eye has fallen on a news item about whaling laws being openly and flagrantly broken. They’re wiping the bloody points of their harpoons on the paper the international agreement’s written on and laughing their heads off.

Whale meat is a luxury item that no one really needs. Although I do feel sympathy for those few Inuits who want to follow the whaling traditions and diet of their ancestors, I would prohibit them from whaling as well.

When pirates threatened merchant vessels and pillaged cargos in the waters off the Horn of Africa, mine-carriers and battleships were sent from all over the world. Piracy and lawlessness shouldn’t be tolerated, of course, even if it’s motivated by hunger and misery.

When intelligent creatures who are an integral part of marine nature and are no threat to anyone are being hunted to extinction—an extinction that no effort can ever reverse, unlike the loss of the trivial cargo of those freighters—the most you see is Greenpeace’s rickety vessel when there’s every reason to have a couple of real, authoritative-looking battleships with UN flags flying to announce that they’d better let go of those harpoons if they don’t feel like going for a little swim.

Why is the protection of property so self-evident, so obvious, while giving other creatures their right to live is so difficult and complicated?

The argument over animal rights, or the lack thereof, is exactly like the argument we had long ago about the supposed inferiority of the nonwhite races. Or women.

That they may have seemed like thinking creatures, but what looked like intelligence was just a product of instinct, mimicry, a lower order of nature’s creation striving towards our own image. At best we might concede that they were some sort of noble savages with a certain kind of cleverness, even almost a glimmer of a soul. But women and blackskinned people weren’t really worthy creatures. Slavery and misery were all they were fit for because they didn’t really suffer. The laments that came out of their mouths meant less than the whine of a kicked dog because dogs could at least be valuable, useful.

A day will come when people will cringe at the thought that their forefathers ate birds, other mammals and the people of the sea without regret. To them this will sound as barbaric and revolting as the fact that some primitive human populations ate members of their own species is to us.

Everything happens a step at a time. Defenders of oppressed groups will emerge from the ranks of those that hold power, first a few then more, until no one in any civilized country will say publicly any longer that feeling, thinking creatures shouldn’t have rights and freedoms.

Already many people who still wolf down beef and pork without a care won’t eat whale, dolphin, elephant or ape meat because so many sources tell us of these creatures’ intelligence. Dolphins and primates have even been given their species’ rights. In Spain they affirmed primates’ right to life and freedom from torture and exploitation back in 2008.

But I don’t know if anyone is policing that clause any more than they do the whalers.

LEAVE A COMMENT (total comments: 1)

USER NAME: Seppo Kuusinen

I agree that endangered species shouldn’t be hunted.

But where in the world are you going to draw the line once you start giving animals rights? Human rights are easy to understand because humans are a species that is conscious and behaves like a conscious creature. Animals are more like machines or robots. Like computers, they react to the outside world in complex ways, but there’s ‘nobody home’.

They don’t have language, science, art, technology or any kind of culture. Is there any evidence of their so-called intelligence? Where are their cathedrals and monuments? Animals have instincts and reflexes, but only humans make choices.

DAY NINE

I am a fleer from evil, a dodger of difficulty.

I could at least sometimes not avoid the things that I know are going to turn out badly or upset me or cause me extra trouble. How many times have I left an email unopened for days when I know the sender can’t have anything pleasant to say to me (the tax man, Marja-Terttu), gone online to change my appointment for a check-up at the dentist that’s already been put off too long, avoided looking at a stain on the shower wall that might be an omen of expensive and difficult-to-repair water damage?

This trait might make my choice of profession seem an odd one. But in my profession I don’t make anyone upset or unhappy, not even myself. The tough, unavoidable part has already happened, and it’s my job to take charge of the cold practicalities. I may not want to examine the stain on my own shower wall, but I would have no trouble answering a call about suspected water damage somewhere else and setting out with my toolbox swinging to make a house call and attest that it is, indeed, mould. You have a problem; I have a solution.

But unpleasantness, misfortune, wrongs that concern me I prefer not to face. It’s a trait I no doubt share with the rest of the world. We prefer to put off inconvenient truths until the very last minute.

Maybe recent events are a sign that I’ve evaded and sidelined unpleasant realities so long that some cosmic cistern has finally been filled to the brim.

It’s been nine days since I saw that one of the hives was empty.

Nine days since I saw the blue lights flashing at the Hopevale meat plant.

Things happen in bunches. Good fortune brings more good fortune, and bad luck is always followed by more of the same.

Going to the hives now is like knowing that the superpowers have been threatening each other for a long time, and they’ve set a time when the missiles will emerge from their silos if the other side doesn’t submit to their demands, and now that deadline is at hand and I ought to turn on the television and see if the end of the world has arrived.

Almost everything I know about bees I learned from Pupa.

Pupa was there when my memories began, was already in his fifties, which in my eyes was a very old man. Pupa. I insisted on calling him that because it was somehow easier to say than Pappa—a pounding, almost mean-sounding word. He was already bald with liver spots on the top of his head like maps of undiscovered countries that I traced with my finger when I sat on the upper bench in the sauna and he sat on the lower bench taking a breather, grooves radiating from the corners of his eyes like the deltas of great rivers.

He had a name—Alpo—but I rarely remember it. Even on his death announcement it felt like the goodbye was for someone else, some substitute, a puppet representative.

When Ari (whom I, paradoxically, have never managed to call Dad) came to visit from America he always managed to mention to people who happened to stop in for coffee that in America Alpo is a brand of dog food. ‘What are you, Dad, fifty-eight?’ he would say. ‘That’s like eight hundred to you and me. You old dog.’ He especially liked to say it when there were guests present and wink at me, implicating me in the joke, although I tried to look away, carefully balanced between my father and grandfather, not taking either one’s side.

Then Pupa would usually go out to check the hives. He would always go out to the hives or find something to tinker with when anything upset him (like that tired dog-food joke) or weighed on his mind. ‘I’m going out to the hives,’ he would say, getting up in the middle of his coffee, leaving his cookie half eaten. ‘Going out to the hives,’ he would say, and the door would slam as he disappeared into the drizzly evening.

I often followed him. Pupa talked about his bees the way another person might talk about an animal that needed affection and grooming, like a horse that would get lonely out in the barn without regular visits from its master. A horse—maybe I thought of that because of the old-fashioned names Pupa used for the hives and their accessories. He called the removable inner box the bee pony. And the worker bees and drones were hens and cocks. ‘Cocks, cocks’, it reminded me of the noise when the hives caught May Disease, flight lameness. Spores had got into the honeycombs, and the bees came out of the hives in a group, fell down in front of it and bumbled and buzzed in the meadow grass, struggling vainly to f ly. When you stepped on them they would make a sound like ‘cocks cocks’. Pupa swore like mad, had to shovel the dead and dying bees from around the hive into a zinc bucket and dump them on the compost heap. The hives he burned.

The lameness was comprehensible; it was a disease, it had a cause, like dyspepsia or embryonic plague (Pupa used old names for diseases, too, and I’m sure he would be horrified at how many and multifarious the threats to the bees are nowadays). Diseases didn’t empty the colonies completely like the bee collapse does, the hives a riddle like the Marie Celeste, that ship found on the open sea, empty, warm food still on the table, a parrot in the captain’s cabin who no doubt knew what had happened but couldn’t speak, at least not well enough or in a way we could understand.

Parrots.

They make me think of Eero.

Like so many things do.

Thinking of Eero sends an icy wave falling into the pit of my stomach, a horrible stab, and I gulp for breath, jerking the air into my lungs in long sobbing breaths.

There’s nothing else I can do.

I go out to the hives.

Excerpted from The Blood of Angels © Johanna Sinisalo, 2014