Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a weekly column dedicated to doing exactly what it says in the header: shining a light on the some of the best and most relevant fiction of the aforementioned form.

Having joined forces before on Fortunately, the Milk… as well as illustrated editions of The Graveyard Book and Coraline, Neil Gaiman and Chris Riddell have a history. The Sleeper and the Spindle is their latest collaboration, and undoubtedly their greatest to date.

As a work of fiction, most folks will find it familiar, I figure; in the first because it’s a refashioned fairy tale based in part on a couple of classics—specifically Sleeping Beauty and Snow White—but consider this in addition: The Sleeper and the Spindle has been published previously, albeit absent the art, in Rags & Bones: New Twists on Timeless Tales, in which anthology the story was very much at home.

The real hero of Bloomsbury’s exquisitely illustrated edition is Riddell, then. His pen and ink portraits and landscapes add a delightful new dimension to the text, and though they were added after the fact, they don’t seem in the slightest superfluous; on the contrary, they belong in this book. That said, this is the Short Fiction Spotlight, so our focus must be on the story, which—whilst neither shiny nor new—well… it’s still swell.

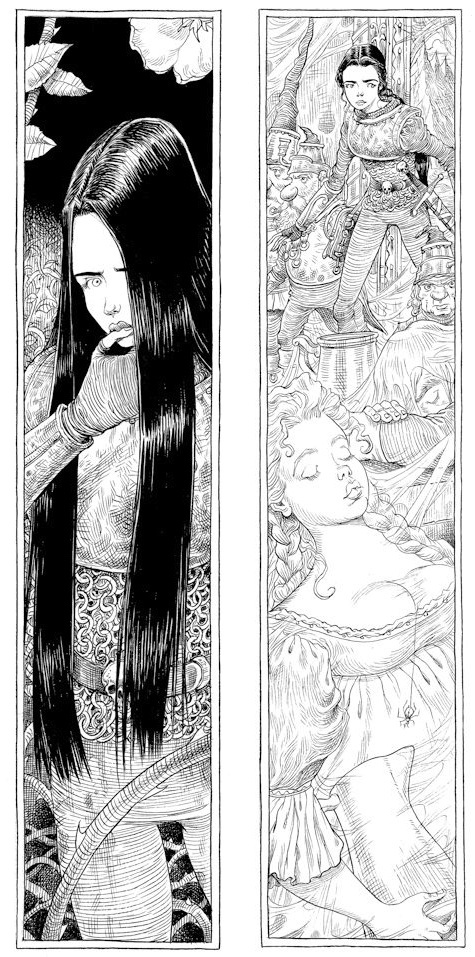

Above all else, The Sleeper and the Spindle is an exploration of identity. As the narrator notes, “names are in short supply in this telling,” so instead of Snow White, we follow the queen—recently renewed after a magically-induced snooze—on a quest to save the princess of a neighbouring kingdom; Sleeping Beauty, we suppose… though her highness is also altered.

It’s natural enough to wonder why the queen all people would undertake such a task—aside from sympathy with someone under the spell of a similar sort of sleeping sickness as she herself suffered—but Gaiman clues us in quickly, offering up a remarkably revealing explanation in the queen’s first scene; a week from when, we learn, she shall be married:

It seemed both unlikely and extremely final. She wondered how she would feel to be a married woman. It would be the end of her life, she decided, if life was a time of choices. In a week from now, she would have no choices. She would reign over her people. She would have children. Perhaps she would die in childbirth, perhaps she would die as an old woman, or in battle. But the path to her death, heartbeat by heartbeat, would be inevitable.

Unless something drastic happens. Unless the queen sets about determining her own identity.

And so she does over the course of the story, by chucking Prince Charming “beneath his pretty chin”—brilliantly—before abandoning her lavish palace and staff of servants for a network of treacherous tunnels known only to the band of besotted dwarfs she travels with.

Soon, but not soon enough, she arrives in the princess’ kingdom, where the sleeping sickness has spread. Everyone her company encounters is evidently infected, and in the thrall of this condition, they’re unwittingly vicious—like zombies, or puppets, perhaps, of some dastardly mastermind:

They were easy for the dwarfs to outrun, easy for the queen to outwalk. And yet, and yet, there were so many of them. Each street they came to was filled with sleepers, cobweb-shrouded, eyes tight closed or eyes open and rolled back in their heads showing only the whites, all of them shuffling sleepily forward.

Strange to see such things in a fairytale, eh? Surprising, too—though it really shouldn’t be—to have a queen for a hero in such a story, not to speak of a queen with actual agency: a female character able to effect change rather than simply suffer it in attractive silence, as I imagine the old guard would have it.

The identity of The Sleeper and the Spindle’s eventual villain is equally unexpected, and similarly satisfying in its shattering of certain stereotypes, but I’m going to leave that last for you to delight in discovering.

Gaiman gets a lot of meaningful mileage out of these deceptively simple twists, but even absent these, The Sleeper and the Spindle would remain a massively satisfying story: a seamless smooshing together of the two tales it takes its inspiration from, as sweet as it is subversive.

And this new edition is—I can’t resist—the perfect gift, in no small part thanks to the embarrassment of riches Chris Riddell’s meticulous illustrations represent. I challenge anyone to feel anything less than love for The Sleeper and the Spindle. It’s fun—for all the family, in fact—and truly beautiful too.

Not merely in appearance, either.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.