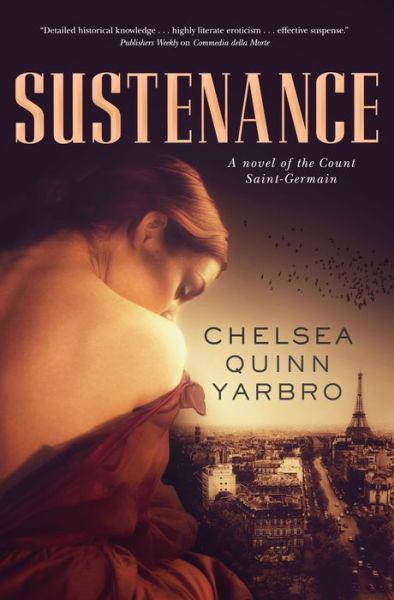

The vampire Count Saint-Germain protects Americans fleeing persecution—and becomes trapped in a web of betrayal, deceit, and murder in post-WWII Europe in Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s Sustenance, available December 2nd from Tor Books!

The powerful House Un-American Activities Committee hunted communists both at home and abroad. In the late 1940s, the vampire Count Saint-Germain is caught up in intrigue surrounding a group of Americans who have fled to postwar Paris. Some speak out against HUAC and battle the authorities.

Saint-Germain swears to do his best to protect his friends, but even his skills may not be able to stand against agents of the OSS and the brand-new CIA. And he has an unexpected weakness: his lover, Charis, who has returned to Paris under mysterious circumstances.

One

It was one of those probably nothing noises, a sound that was part scrape, part yowl, a bit sneaky, and it brought Charis Treat abruptly awake, her pulse racing, words whispering out of her at machinegun speed. “It was a tree branch, or an angry cat, or something at the docks, or—” Or anything but the CIA bugging her Copenhagen hotel room. She sat up in bed, holding the pillow in front of her like a shield. Striving to separate herself from the fear that made her hands shake, she used her most reasonable lecture voice: “You’re in…” It took her a couple of seconds to remember. “You’re in Denmark, not Louisiana. You don’t have to worry about the Committee, not here.” Her voice was louder now, and she was breathing more normally. She forced herself to yawn, not very successfully, then she got up and went to the cramped bathroom, where she took a second phenobarbital and an aspirin, used the toilet, and went back to bed. Her alarm clock on the night-stand told her it was four-thirty-seven. “Damn,” she muttered. She would need to get back to sleep quickly if she were going to have sufficient rest when her breakfast tray arrived at six-forty-five. If only she did not have to be off for her interview by seven-thirty. She sighed and got slowly back into bed, ordering herself not to stare at the ceiling, trying to imagine what Harold and the kids were doing; that was something she would find out later. It would be a mistake, she thought, to go to her interview overcome by melancholy. “Be sensible. They’re fast asleep,” she told herself aloud. “Just as you should be, Charis.” She often lectured herself sternly in the waning hours of the night, had done so since she was in grammar school. Now she leaned back and rested her head on the goose-down pillow, willing herself to sleep.

After nearly an hour of watching the shadow-pattern of the birches’ falling leaves in the hotel garden dancing and sliding on the wall, she sighed, reached out, and turned on the bedside lamp; its yellow glow created a cone of light that allowed her to resume reading Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country. She managed to get through another twenty pages before the first signs of the advancing dawn suffused the room with thin, limpid light. Marking her page with a brass paper clip, she set the book down, turned off the light, and did her best to get at least enough of a doze to restore her to the semblance of alertness.

“Breakfast, Madame,” said the waiter in acceptable English as he rapped twice on her door.

“Coming. Thank you,” she said, dragging on her bathrobe as she got out of bed and into the chilly morning; she made her way to the door. “Put it on the table,” she said, thinking it was absurd to tell the young man that, since there was no other surface in the room that would reasonably accommodate the tray.

The waiter offered her a neat little bow and set the tray down, and handed Charis the bill on a kind of clip-board.

Charis went to pull her purse out from under the pillow, opened up her wallet, and removed four coins—the same amount she had paid every breakfast for the last four mornings—and went to close and lock her door as he left. “Eggs, toast, herring, tea,” she said as she lifted the lids on three plates, stacking them together on the remaining wedge of empty tabletop. The first day she had asked for orange juice as well, but was amazed at the cost, and had dropped it from her subsequent breakfasts. The eggs were soft-poached, just the way she liked them, and there was a little ramekin of fresh butter next to the two slices of toast. The herring was broiled. Not what she would have back home, but not too foreign, either. She fit the strainer on top of her cup and poured out the dark, leafy tea through the fine wire mesh, concentrating on not overfilling her cup, as she had done yesterday. There was so much to get used to! “Book your call for six this evening,” she reminded herself aloud as she pulled up the overstuffed chair from next to the bed and began to eat, keeping an eye on the clock.

The noise that wakened her returned, and this time she realized it was the squeak of brakes on the delivery van that had just unloaded the day’s produce at the hotel’s kitchen door. She made herself chuckle at her fears, saying, “Next you’ll be jumping at phone calls.”

When she was finished with her meal, she went into the bathroom to wash and put herself in order. At thirty-six, she was still passably attractive, especially for an academic, she thought wryly, but she knew enough to be careful with her make-up and hairstyle, to put the emphasis on her best features, which were her large, smoky-blue eyes and her teak-colored hair. She wished she had a shower, but made the most of a quick turn in the tub. The towel she had been provided was a pale blue, a bit threadbare, and scratchy. She rubbed herself down quickly and then took a minute to stare at herself in the mirror. She patted the dark smudges under her eyes and decided to use her Elizabeth Arden foundation—it gave the best coverage. She took a moment to pluck a few stray hairs from her dark, angled brows, and sighed. “I’ll have to rely on charm, I guess. Looks aren’t going to do it today.” She applied her make-up with care, hoping to conceal the anxiety that had taken hold of her; it would be foolish to reveal how desperate her situation was becoming.

She left her room a few minutes ahead of schedule, her fawncolored wool jacket long and princess-cut over an ecru blouse an understated version of Dior’s New Look. Her skirt was not quite the right length for sticklers, but its deep Prussian blue matched her gloves, her shoes, and her hat. Her purse was a simple dark-blue clutch—shoulder bags had vanished from American stores when Hoover had declared that Communist sympathizers carried them— and her briefcase was a darker version of her jacket. All in all, she was pleased with the impression she could make.

The expression on the face of the clerk at the front desk confirmed her good opinion; he took her order for an eighteen-hundred-hours call to America, saying, “Will you take it in your room or in the telephone lounge?”

“I think my room would be better, thank you,” she said, wondering if she should tip him.

He recognized her predicament. “Gratuities are offered when the service is complete.”

She could feel her face grow warm. “Thank you,” she said again, and added, “Your English is very good.”

The clerk smiled. “My parents sent my brothers and me to our aunt in Canada during the war years.”

“Probably sensible,” she said, missing her own sons, and turned toward the entrance. Stepping out of the hotel, she asked the doorman to hail a cab and gave the driver the address she had memorized the night before. “I understand we should need about twenty minutes to thirty minutes, perhaps a little longer. The roads won’t be crowded yet. In half an hour, they will be.” He swooped into the street and lit a cigarette. “I will have you there shortly after zeroeight-hundred. I know a shortcut.” He grinned around the cigarette and signaled to turn left, making a rude gesture with his hand.

The morning was nippy—not quite cold, but chilly enough to make her think she had been wrong not to wear a coat. She settled back in the cab and watched the traffic around her, but gradually anticipation of the morning’s meeting claimed her thoughts: she tried to decide what she would say to this Ragoczy Ferenz, Grof Szent-Germain; how should she address him? In what language? Did he speak English? French? She knew a little Italian, but not enough to discuss her book in it. She suspected he was Hungarian: the sz looked Hungarian, but it might be Polish or Czech. Probably not Russian: Russians weren’t supposed to use titles like Grof any longer, unless he was one of the Old Regime, whose family fled before the Revolution. Certainly not Bulgarian or Croatian or Serbian or Montenegron, and probably not any other Jugoslavian ethnic group; for a while she mentally ran through the list of nationalities that Grof Szent-Germain might be but probably wasn’t. She resisted the urge to bite the end of her little fingernail, telling herself it would smear her lipstick. The cab took an energetic turn to the left, and she grabbed the loop hanging down between the front and rear seats.

“Sorry; there was an obstacle in the road,” said the driver, who was on his third cigarette.

“So I gather,” said Charis, adjusting her hat and sitting back once more.

The driver double-clutched down into second gear and climbed up a small rise; the street was very narrow, with ancient cobbles and the narrowest of walkways along the edge of the stones. The buildings here were old—most a couple of centuries at least—Charis realized, and wondered why a publishing house should be in this older part of the city. She was more startled when the driver turned into an even smaller side-street, barely wide enough for the cab to negotiate, and drew up in front of an elegant four-story building that looked to be about three hundred years old. “Number 32, Madame,” said the driver as he flipped up his trip-flag, and told her the price. “It’s zero-eight-hundred-twelve.”

She worked out the fare in American dollars: one-twenty-eight, more or less, yet another reminder of how the war had driven up the price of fuel and of operating a car. She handed over the appropriate coins, which still seemed dreadfully unfamiliar to her. “Thank you,” she said, letting herself out with care onto the narrow strip of brick sidewalk, her purse in one hand, her briefcase in the other; the cab was put into reverse and backed away from Charis’ destination.

It was in beautiful repair, she thought as she climbed up to the front door, pausing to look at the various ornaments above the windows: most of it was scroll-work in a subdued Baroque style. Reaching the broad top step, she saw the modest bronze plaque above the knocker:

Eclipse Publishers

and

Translation Services

and above that was another one, saying, she assumed, the same thing in Danish.

Charis hesitated, her confidence faltering, then remembered that Harold had not sent her the full hundred and fifty dollars he had promised her; she grabbed the knocker and swung it down on its strike plate twice and waited for someone to answer.

Roughly a minute later, a man who looked to be about fifty, with sandy hair touched with white and eyes the color of old, muchwashed blue jeans, opened the door. He nodded to Charis. “Professor Treat?” he asked in English; his accent was almost flawless.

“I am,” she said, trying to conceal her sudden return of nervousness with a smile. “I’m a little early, but I don’t know the city and didn’t want to be late.”

“Please come in; I’m Rogers, the Grof’s personal assistant,” he said, stepping back and opening the door wider into a two-story entry hall with a single, broad staircase leading to the gallery circling the hexagonal room one floor up. He indicated a comfortable drawing room on Charis’ right. “If you’ll be seated, I’ll tell the Grof that you’ve arrived.”

“Thank you,” she said, and glanced in at the muted blue-green walls and several large, oaken bookcases filled with hard-bound editions of all kinds, some looking to be almost as old as the building. Two sofas and a coffee-table stood in front of a handsome fireplace; the whole room was alight with watery sunshine.

“May I bring you some coffee or tea while you wait?”

“Will that be long?”

“Well, as you say, you are early, and the Grof is in a meeting.”

She hesitated, worried that her appointment might be cut short because of her early arrival, which might be seen as American pushiness; she knew Europeans disliked it. “Coffee,” she said when she realized that Rogers wanted an answer. “With milk, no sugar.”

“Very good.” He nodded again and left her to inspect the shelves, hoping to learn more about what Eclipse published.

She had removed her gloves and was perusing a volume on the archeology of the Peruvian Andes, translated from the French; the date of publication was 1948, and the book was printed on coated stock with wonderful photographs, many in color. This was most encouraging, she decided, and turned around to find Rogers returned with a tray holding a large cup-and-saucer, a plunger coffeemaker, and a jug of milk. “Oh. Good.”

“Shall I set it down, Professor Treat?”

“Yes, please,” she said, putting the book back on the shelf. “It’s quite fascinating, isn’t it?”

“Professor de Montalia’s work? Yes, it is,” Rogers agreed as he placed the tray on the coffee-table. “The Grof will be with you shortly. He has been in a meeting with his printing staff, and they’re going to run over—something about the new presses. He apologizes for the delay.”

“Thank him for informing me,” she said as she went to the nearer sofa and sat down, reaching for the small lacquer-work tray as she did.

Rogers nodded toward the fireplace. “Would you like me to light the kindling?”

The room was a little cool, and without a coat she was growing uncomfortable; she did not know how much longer she would be here, she reminded herself as she depressed the plunger on the coffee-pot. “If it isn’t inconvenient for you, that would be nice.”

“No inconvenience at all.” Rogers went to a small, antique secretary and removed a box of fireplace matches, then moved the firescreen and lit the kindling under the quartered logs. He remained where he was until he was satisfied that the logs were starting to burn. “If you need anything more, please press the button by the door,” he said, putting the fire-screen back in place, and going away.

“Thank you,” Charis called after him, then added milk to her coffee and tasted it, knowing it was still very hot. She set the cup down and rubbed her tongue on the roof of her mouth, feeling the first onset of interview-jitters take hold. Somewhere in the house, a clock sonorously rang the half-hour. It was the time appointed for her interview; in spite of all her good intentions, Charis began to fret. She drank her coffee and added more from the pot.

Some five minutes later, she heard crisp footsteps approaching through the entry hall, and thinking this was Rogers coming to fetch her, she reached for her briefcase, preparing to rise.

A moment later, a man of slightly less than average height, graceful yet sturdily built, came through the door. He appeared to be in his middle forties, had well-cut dark hair with a slight feathering of gray at the temples, and an angled arch to his brows; his face was more attractive than handsome, with a broad forehead and a slightly askew nose, his eyes an arresting, strange blue-black. He was dressed in a black suit of understated elegance. His shirt was off-white and obviously silk, as was his dark-red damask tie. His waistcoat had a subtle pattern of what looked like wings in its fine black wool. “Professor Treat. Thank you for waiting,” he said in English with a faint accent she was unable to identify. “And I apologize for the early hour, but I will be leaving Copenhagen tomorrow and wanted to see you before I left, which is why I suggested an eight-thirty appointment.” His voice was low and musical, and his manner, though formal, was welcoming.

“Grof Szent-Germain,” she said, recovering herself, and, starting to rise, held out her hand, while struggling to get out of the deep sofa cushions.

He came closer and took it, bowing slightly. “A pleasure, Professor Treat. Welcome to Eclipse Publishing. I trust your journey was a pleasant one.”

“Thank you,” she said, standing up a bit awkwardly. “The cabdriver smoked a great deal.”

“And your journey from America?” he asked.

“When is a long flight ever comfortable?” she asked, wanting to seem more broadly traveled than she was.

He offered a wry half-smile, saying, “I concur, especially over water,” then motioned to her to be seated, and took his place on the sofa opposite hers. “Before we begin, let me assure you that I am aware of the lamentable developments in the United States. It is a difficult time for academics in your country, is it not?”

“America has always had a streak of anti-intellectualism in its make-up,” she said, using her lecture tone. “When the people are frightened, they often seek refuge in religion and reject science. Science is not often comforting.”

“They reject knowledge out of fear,” he added.

“Out of fear,” she agreed.

He shook his head. “I hope you are finding a better reception here in Denmark. And in Paris, for that matter.”

“I hope so; most everyone has been polite, but I don’t speak Danish, and that is a problem for me,” she said, and reached for her coffee-cup to finish what was left in it, wanting her throat to be less dry. “I have pretty good French.”

“The French will appreciate that,” Szent-Germain said with a sardonic lift of one eyebrow.

Charis managed an uneasy chuckle.

“I’ve noticed you have the name Lundquist in your query-letter,” he went on in the same easy manner.

“My maiden name,” she said, and felt herself blush. “With my situation being what it is, I don’t want my… political difficulties to reflect poorly on my husband or my sons. By my using my maiden name, Harold can protect his place at Tulane.”

“I thought it might be something of the sort,” Szent-Germain told her in a deliberately neutral tone. “If you will be kind enough to tell me what I may do to help you achieve what you are seeking?”

“That’s why I’m here,” she said, and then tried to explain herself. “Not that I want to impose upon you, but I would like to find a publisher who can produce my work without being in danger from the government. As I told you when I first wrote to you and mentioned my work, I’m aware that many publishers are… chary about what topics they consider. Your reply was encouraging, and so I’m hoping you don’t feel constrained to follow the example of American university presses. I’d be grateful if you would consider my work for that reason alone, but I have learned that Eclipse Publishing has an enviable reputation, and that adds to my hope that your company will want my book.” She patted her briefcase. “I have a copy of my current manuscript here, which I would like to submit to your Editorial Board. I was hoping to discuss that with you, as well as what other sorts of books you are seeking.”

“You have more projects in mind?” The flicker of amusement in his dark eyes took the sting out of his question.

“Yes,” she admitted. “Several.”

“Very wise. It’s always useful to have new works in progress. It keeps thoughts fresh.” He offered another brief smile. “Will you leave that copy with me? I’ll take care to get it to the Board. If it’s accepted, we will discuss further works.” He got up from the sofa but only to ring for Rogers. “Would you like more coffee, Professor Treat? Or would you prefer Lundquist?”

“Treat will be fine.” She was about to say no to the offer of coffee, but changed her mind. “Yes, please.” She suddenly felt very vulnerable; she gathered up her courage and went on. “I am in contact with other American academicians who are seeking publication abroad, since they cannot find any editor at home willing to—” She broke off. “May I tell them how to submit manuscripts to your Editorial Board and peer review? For the most part, they’re in a similar predicament to mine: trying to do work while improvising a living here in Europe.”

His enigmatic gaze rested on her for almost a minute before he said, “I have an information packet that Rogers will give you when you leave. Another pot of coffee for Professor Treat, and more milk.” This last was to Rogers, who had come to the open door. “And a copy of our submissions protocol,” he added.

“It will be ready when she departs,” said Rogers, and went away.

The Grof turned back to her. “Now, if you will tell me a little about your book? Just the barest outlines, if you will—and some idea of its level of scholarship. Do you intend it for university students, or a more general readership?”

“For university level students of history or anthropology,” she said. “And perhaps some of the general public with such interests— history buffs and the like.”

“And how do you present your material? How academic is your style? Might a well-informed layman be able to read it without difficulty?” He sat back and propped one ankle on his opposite knee; she saw that the soles of his shoes were unfashionably thick, and was diverted by this little vanity; so many short men, she thought, wanted to be tall.

“I hardly know where to start,” she said, his inquiry having taken her by surprise.

“Then please begin with the title.”

She took a deep breath. “Social Structures of Communes and Communards in Medieval Europe. I’m primarily interested in social structures as they relate to folklore and cosmologies of the past, but the difference between Western Medieval societies before the Black Plague and afterward was so compelling that I used this for my work.” She paused, then added, “Europe had to reinvent its social structure.”

“Compelling,” Szent-Germain repeated, recalling the terrible years that began with the first epidemic and the chaos he saw everywhere he went; the Plague continued on for more than a generation through two additional, less catastrophic epidemics, and in the end he had gone to Delhi to avoid the ruin in Europe. “The Black Plague was… harrowing,” he added. “So few survived.”

“But I touch only a little on the Plague itself,” she said, a bit defensively.

Szent-Germain’s laughter was more sad than mirthful. “But focusing on the communes: no wonder you couldn’t find a publisher in America for such a book in these times.”

“Exactly,” she said, relaxing a bit when he said nothing more. “The Dean of the History Department advised me to burn the master copy and my notes, then refused to consider any paper I submitted for his opinion. The Dean of the Anthropology Department refused to look at it at all. Tulane has been pressured about what they teach, and it isn’t the only university to discontinue research if the subject of the research displeases men in high places.”

“A prudent notion on the part of the two deans, under the circumstances, but certainly against all the principles of scholarship. I am honored that you decided to approach Eclipse with your work.” He held out his hands for the manuscript. “I trust you have other copies, and that they are protected.”

“Yes,” she told him, a touch of defiance in her posture; she removed the manuscript in its heavy cardstock file from her briefcase and passed it to him. “I have them in the safe at the hotel.”

“Very wise. Take care to keep them under lock and key throughout your travels.” He got up again and went to put the manuscript in the second drawer of a tall, old-fashioned wooden file cabinet. “As I will here.”

She had to fight down a rush of fear as the lock clicked audibly. “Can you let me know how long it will take your Editorial Board to reach a decision? I’m returning to Paris shortly, and I want to know what information you will need to reach me.”

“I would say between two and three months for the Board to decide, all things being equal, assuming there is no delay in getting my new presses installed and working. Two of the old ones were reduced to scrap during the war. If there is going to be any delay, Rogers will contact you as soon as possible.” He came back to the sofa just as Rogers brought another small tray into the room, set it down and removed the one that was there, then left silently.

“Will you have some, Grof?” she asked, more from good manners than desire to share.

“Alas, no. Coffee does not agree with me.” He resumed his place on the sofa. “How long have you been in Europe?”

“Not very long; a little over four weeks,” she said, her hand shaking a little as she depressed the plunger.

“You have come alone? Or have you someone waiting for you in Paris?”

There was such gentleness and sympathy in his question that she felt the welling of tears in her eyes; she looked away to conceal them, coughing a little before she answered. “My husband and sons are still in New Orleans. For now, we agree that it is wise for him to remain there. Arthur, my older son, has polio and neither his father nor I believes that his treatment should be interrupted.”

He nodded. “How unfortunate for you, Professor Treat. For all of you,” he added.

“That’s very kind of you.” She poured the coffee into the new cup Rogers had left, and added milk from another little jug.

“I do not mean to pry, but I have seen a number of Americans— not all academics—in similar circumstances,” he said. “I take it your husband does not teach.”

“Most of his work is research, but he does have grad students; he is a soil chemist taking part in a governmental series of experiments; the project is in its fourth year. Had I remained with him, he would most likely have had to leave his job, and might not find work easily.” She swallowed hard and lifted her chin. “I’ve scheduled a call to him this evening.”

“Very good,” he approved.

She picked up her cup and sipped. “I want to give him some encouragement,” she said before she could stop herself.

“About the book? You may certainly tell him that it is under consideration, and that you will have a response by mid-February if all goes well,” he said to her. “The Editorial Board will meet just after the new year. I will send a copy to each of the members in a week.”

“That should relieve him,” she said, and wondered what form that relief might take.

“I cannot yet promise you a contract, for I haven’t read your manuscript—oh, yes, I do read what I publish—but your topic is intriguing. I, myself, have some knowledge of those times, and I’m inclined to believe that it is an area of study that has been neglected. Your work will receive close attention: believe this.”

“Oh,” she said, feeling less nervous with this revelation. “Any location or period in particular? that you have studied?”

“Praha—Prague—during Otakar the Great’s reign, and Padova in the decade before the Black Plague, among others,” he said. “Would you like to discuss these periods when I return to Paris, if you will still be here?”

“I would be delighted,” she said with enthusiasm. “How long will you be gone?”

“Ten to fourteen days, or that is presently my plan,” he said, and saw her face fall. “I’ll be in Amsterdam for a week; Eclipse Publishing Amsterdam is also getting new presses installed, and I expect to be there for the event; beyond that, I cannot anticipate how long I will need to remain with the various branches of my company. After Amsterdam, I have business in Venice, including a branch of Eclipse Publishing. I’ll be in Paris after that, and keep you abreast of any changes in my plans.” He watched her more closely than she knew, and saw the little moue of disappointment touch her mouth. “I will have to be in Paris for three weeks in November. Perhaps we might meet then?”

She restored her calm. “I’d like that very much.” Then she chuckled at her own confusion. “I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have put you on the spot like that,” she said, and took another, longer sip of milky coffee. “Be good enough to chalk it up to my American ways.”

“Hardly on the spot,” he said, and continued genially, “I’ve been to your country, you know, and have some understanding of American ways. I was there shortly before war broke out. I drove from Chicago to San Francisco. It’s quite a remarkable place.”

Mentally chastising herself, she said, “Which crossing did you use? Forty? Sixty-six?”

“Forty,” he answered.

“Then you haven’t seen the Gulf Coast,” she said.

“No, which is unfortunate,” he confessed, and, after a brief pause, remarked, “You will pardon me for saying it, but your accent does not seem to be of the American South. I would have supposed you came from Illinois, perhaps, or Michigan.”

“Neither. I was born in Colorado, but grew up in Madison, Wisconsin. My dad taught at the University of Wisconsin. I did my doctoral studies at Chicago, and taught at Wake Forest in North Carolina for two years. Someone in the southern academic grapevine recommended me to Tulane. I’ve been on the faculty there for nearly a decade.” She coughed once, afraid she might sob instead, and resolutely went on, “As a Coloradan, I have to know what you thought of the Rockies.”

“Even an old Transylvanian like me must be impressed with the Rockies, and the Pacific Ocean.”

“Transylvanian?”

“Romanian, if you like. In the east end of the central plateau of the Carpathian Mountains, to be more specific,” he said.

“The USSR holds that territory, don’t they?” she asked, then put her hand to her mouth, finally saying, “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean—”

“For now, the Russians are in charge. The Hungarians have been several times before, and the Ottomans. The Romans gave the country its name, but the Daci were there before them, as were many others.” He met her eyes with his own steady gaze. “These things change, with time.”

“You’re an”—she tried to choose a more polite term, but could not—“exile?”

“For most of my life,” he said.

“I’m so sorry,” she responded. “No wonder you understand my situation.” As soon as she said it, she flushed with embarrassment. “I wish I could say something more comforting.”

“You need not,” he answered. “I’m used to it.” He shrugged and changed the subject. “Shall I let you know when I plan to arrive in Paris?”

She nodded. “If you would, please.”

“If you will provide an address to Rogers before you leave? Thank you.” He rose. “It has been a pleasure to meet you, Professor Treat. I must thank you for coming to Eclipse Press before seeking out another publisher.” He saw the astonished look in her eyes. “Well, you have not been in Europe very long, so what should I think than that Eclipse was your first choice?” With a half-bow, he took a step away. “I am sorry, but I must leave. Do finish your coffee. Zoltan will drive you back to your hotel whenever you like.”

She watched him cross the entry-hall and vanish down a corridor on the far side of it. She sighed, trying to decide if she had succeeded or failed in this most perplexing interview. She wished she knew what to make of Grof Szent-Germain, and almost at once frowned as she strove to come up with a description she could offer to Harold when they spoke that evening. Twenty minutes later, as she left Eclipse Publishing, she had convinced herself that the less she said, the better it would be.

Excerpted from Sustenance © Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, 2014