In the remote city of Lushan, they know that the Fey are not fireside tales, but a dangerous reality. Generations ago, the last remnants of a dying empire bargained with the Faerie Queen for a place of safety in the mountains and each year the ruler of Lushan must travel to the high plateau to pay the city’s tribute.

When an unexpected misfortune means that the traditional price is not met, the Queen demands the services of Teresine, once a refugee slave and now advisor to the Sidiana. Teresine must navigate the treacherous politics of the Faerie Court, where the Queen’s will determines reality and mortals are merely pawns in an eternal struggle for power.

Years later, another young woman faces an unexpected decision that forces her to discover the truth of what happened to Teresine in the Faerie Court, a truth that could threaten everything she loves.

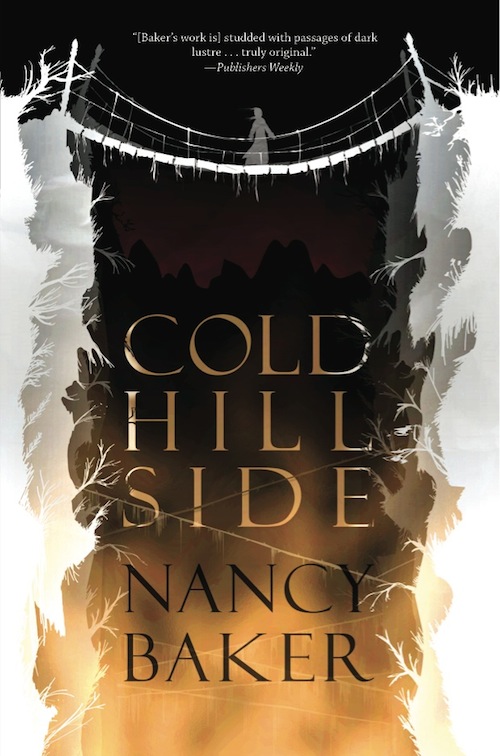

From acclaimed author Nancy Baker comes Cold Hillside, a new novel about the price of safety and the cost of power—available November 18th from ChiZine!

CHAPTER 6

Lilit

The next morning, Lilit was at the Auster compound before dawn. She was early, but some of the house-sisters were already up, having been deputized to get the horses from the stables outside the city. In the old days all the great Houses had included stables within their compounds but over the years that space had been claimed for human use. Now the only horses within the city belonged to the Sidiana and the royal household. The rest of the Houses kept their own stock outside the city or hired mounts from the stablemasters there. House Kerias prided themselves on taking only their own horses to the fair; the Austers considered horses a waste of good coin and hired theirs.

One of the Austers, the only one not grumbling at the early hour, was Toyve, who shared Lilit’s apprentice duties in the workroom. “I’m off to get the horses,” she said. “Come with me, before someone sees you, or you’ll be stuck packing boxes. I could use a hand with them.” She dropped her voice with a conspiratorial grin. “The other two they’re sending with me left their wits in the bottom of the arrack jug last night.”

Horses seemed preferable to packing and Lilit joined Toyve and the other sleepy-eyed young Austers on their way out to the stables. A trickle of torch-bearing apprentices from various Houses flowed down the streets and out the gate. The stables lay on the plain beside the shallow Lake Erdu, where the shaggy, stocky mountain horses could graze on the tough grass.

Lilit followed Toyve and the others into the low-walled compound and a scene of such chaos that she could not imagine how the caravan could possibly leave before the snows came, let alone that day. Stable urchins darted through the shadows in a manner that seemed determined only by which stablemaster was shouting the loudest. The servants of a dozen Houses jostled in the torchlight and a sea of horses jostled back, snorting discontentedly. Lilit saw Teras and two more of her cousins in a knot of animals, shaking their heads and yelling at the boys who tried to thrust reins into their hands.

“Hiya, out of my way, you lumps. I want better beasts than you,” Toyve cried, pushing her way through the horses, and smacking the occasional equine rump. Lilit trailed after her, accepting the leads tossed her way until she was dragging three reluctant animals in her wake. To her astonishment, the madness settled itself surprisingly quickly and soon she was watching Toyve inspect the tack and hooves of a dozen suddenly quiescent horses.

The mountains were edged in pale light, the spaces between them brightening from black to grey, as they led the little herd back up through the city. Mounted, the journey went quicker and they were trotting into the Auster compound just as the grey became blue. The household was truly in motion now; carefully packed bags waiting to be strapped to the backs of the horses, last-minute instructions being traded, a line of children perched on the upper balconies, watching their elders with curious or envious eyes. Just like at home, Lilit thought as she stood to one side, and felt a pang of loneliness. High above the city, the great bells of the temple boomed; once, twice, three times. The bronze echoes faded and for a moment there was silence in the courtyard.

“Time to go,” announced Dareh Auster. Toyve’s clever, daunting mother had been leading the Auster delegation to the fair for ten years; Lilit had seen her pass at the head of the family procession in the years she had watched Kerias ride out without her.

There was a flurry of embraces, a tear or two. Lilit busied herself with collecting the horse assigned to her, a brown beast with a rolling eye and a sullen look she mistrusted. She found her place at the end of the little procession, beside Toyve and the other chosen Auster cousin, Colum. He gave her a brief smile and she remembered this was his first trip to the fair as well. The thought gave her a brief moment of comfort she clung to with more fierceness than it warranted. Then a great cheer went up from the household, the gates opened, and they were moving out onto the cobbled streets. Door and windows opened, neighbours leaned out to wave. Lilit heard voices rising from other streets and the great bells tolled again, to signify that the Sidiana and her party had begun their journey down the palace road.

Toyve grinned madly at her and she felt her own smile, no doubt equally manic, spread across her face. She waved at the people who waved at her and felt suddenly light, as if she could lift from the back of the plodding horse and soar into the brightening sky like the hawks that circled above the city.

This is the best day of my life, Lilit thought dizzily, and the sun slipped clear of the horizon at last and touched the city with gold.

Five hours later, she was tired and thigh-sore and well and truly weighted to the earth once again. Even the view had paled. She had never seen the mountains that stretched ahead of them and, coming over the pass, she had been dazzled by their white-plumed heights and jagged shoulders. But in the last two hours they had not changed and it seemed she had reached the limit of her awe, or else the limit of her ability to enjoy that awe while her muscles cramped and the small of her back ached.

She twisted in the saddle to look at Toyve, who rode behind her in their single-file trek up a long, scree-sloped defile. “How much farther?” she asked and the other apprentice laughed.

“Two or three hours. We’re making good time. Do you want to go back already?”

“No,” Lilit replied, “but I think you got the thinnest horse.”

“That’s the privilege of the person who has to choose them,” Toyve said. “Besides, you had the better choice at the tavern the other night.”

It took a moment for Lilit to realize what she meant. When she remembered, she was grateful the shadow of her hat would likely hide her blush. “I should have saved my luck for horses,” she said and Toyve’s laugh rang again, turning heads up the line.

At last, they reached the site of the first night’s camp. Lilit slid off her horse to discover her legs had turned to stiff, heavy stalks that seemed to have no connection to the rest of her body. She leaned on the saddle for a moment and watched the rest of the party. As at the stables, what appeared to be chaos soon shifted into bustling order. Most of the sixty members of the fair delegation had made this journey before, of course, from the armoured and helmed guards to the Sidiana herself. Each House was entitled to send six representatives; by custom, three of those places were reserved for the younger members of the household. The meadow in which they camped had been used for generations and the ground held the pattern of the past in firepits of stone. Tradition had established the placement of each House; the royal delegation in the centre, the others in a circle around them.

Through the crowd, Lilit caught a brief glimpse of her Aunt Alder, her hands sketching instructions to the circle of Kerias delegates. She felt another sharp stab of longing and then Colum appeared beside her. “It’s easier to settle the horses if you actually let go of them,” he said mildly and, embarrassed, she straightened and handed him the reins with as much dignity as she could muster. Toyve staggered past, one pack on each shoulder and Lilit hastened to help her.

An hour later, she looked around and discovered that all the work was done; the tents erected, the horses tethered, their precious cargo stowed away, the fire started and the tea already simmering. Dareh Auster emerged from one of the tents and paused to cast a critical eye over their section of the camp. At last she nodded and, when she was gone, Lilit and Toyve let out their breath in simultaneous sighs. “Now what happens?” Lilit asked.

“We make dinner, the aunts meet with the Sidiana, we clean up dinner, the aunts tell us to go to bed early, which we never do, then it’s tomorrow before you blink and time to pack everything up again.”

“And tomorrow we reach the fair?”

“If we get a good start, and the weather holds, we should be there just before dark. Then we work the next day to have everything ready. . . .” She paused dramatically.

“And then?” Lilit prompted, though she knew quite well what happened next. Or at least, what her father had told her happened.

“And then the fair begins,” Toyve said with a grin. Lilit sighed and accepted that her fellow apprentice took far too much pleasure in her superior experience to do more than dole out information in tantalizing tidbits. “But right now, we’d better get the meal started.”

After dinner, true to Toyve’s prediction, the senior Austers made their way to the great royal tent in the centre of the camp. Once they were gone, Toyve set out in search of the best “fire, wine and company.” After a few moments, she reappeared and signalled to Lilit. “House Silvas,” she announced. “Leave Colum to finish up here and let’s go.”

“But—” Colum protested but his cousin waved her hand dismissively. “You’re the youngest. You clean up and guard the tents.” His look turned grimly mutinous and Toyve sighed. “One of us will come back later and you can have your turn.”

“I can stay,” Lilit said, unwilling to be the cause of dissension between the cousins. “The later turn will do.”

Toyve gave her a curious look then shrugged. Colum grinned in gratitude and hurried off after his cousin. Lilit sighed and began to clean the dinner pot.

Dareh, Kay and Hazlet returned before Toyve did. Dareh looked around the neat campsite, nodded to Lilit, who sat beside the fire with the last cup of tea, and vanished into her tent. Hazlet, who had been Silvas before he married Kay, said “Go on then. Send one of the others back to keep watch.”

“Send Toyve,” Kay suggested with a smile.

Lilit nodded, bowed quickly, and set off through the camp. As she neared the Silvas firepit, it seemed that all the apprentices from the camp must be assembled there, crowded in a laughing circle around the fire. She wondered how the senior Silvases felt about the business. Maybe the Houses took turns, so that each had to suffer the exuberance of the junior members in equal measure.

She searched the firelit faces until she found Toyve and Colum, ensconced in the second row on the far side of the circle. With muttered apologies, she squeezed through the ranks and leaned down to tap Toyve’s shoulder. “Here already?” the other apprentice asked.

“Your family is back. Kay sent me—and told me to send you back,” Lilit said.

Toyve sighed loudly and surrendered her place. “Send Colum when he starts yawning,” she instructed, ignoring her cousin’s outraged look, and disappeared through the knot of apprentices behind them. Lilit looked around the circle curiously. The assembly appeared to be waiting for something to happen, though at the moment there was no more than chatter between neighbours and the occasional shouts across the circle. She saw Teras and the rest of Kerias to her right; her cousin caught her glance and waved.

“What happens now?” she asked Colum, who shrugged.

“So far, it’s been mostly singing and stories,” he said and offered her the wineskin tucked into his lap. It held wine, she discovered, but it seemed well-watered and she decided a mouthful or two would be safe enough. It was altogether too easy to imagine an ignoble end to her first fair if she wasn’t careful.

“What’s next?” asked someone across the circle.

“Burden’s Bane!”

“Wine in the River!”

“City in the Clouds!”

Lilit could not quite determine how the decision was made, or who made it, but a bright-eyed young woman with a lute was pushed forward, and, after a fumbling tuning of her instrument, she launched into the old ballad about the scholar Burden and the unanswerable riddle. Lilit had always heard there were a hundred verses, each more far-fetched than the last, but they only made it to twenty-five before the collective will sputtered out and the musician waved her lute in surrender and retreated to her place. She played “Wine in the River” next but stayed carefully seated.

When the echoes of it had died, someone called for a story. This elicited another flurry of suggestions, for both tales and tellers. At last, a dark-haired man rose and stepped into the circle. He paused to add another branch or two to the fire and then looked around the flicker-shadowed faces.

He told the story of the child Iskanden and the tiger, how the young emperor-to-be had tricked his way out of the beast’s claws and come home dragging its skin. Ten years later he had worn the skin as a cloak over his armour as he conquered the known world.

“But that is the old world. The great cities are gone, and the armies, and the riches of far-off Euskalan. So what story should we tell of the new world?”

“Anish and the North Wind,” someone suggested.

“The Drunken Monk!”

“Tam and Jazeret.”

“That’s an old story, Vash,” a girl objected.

“But it’s a good one. And it’s got—”A cry of warning went up from the crowd and the apprentice stopped himself. It was considered bad luck to say the name of the fey on the way to the fair. “—them in it.”

“Tam and Jazeret it shall be then,” Vash agreed to a ragged cheer. The woman beside Lilit made a faint sound of protest and Lilit could not help her sideways glance. The woman returned it, shaking her head in reluctant surrender, but said nothing.

“Once, in the place not here and a time not now,” Vash began and the chatter around the circle died, “there was a girl named Jazeret, who lived in a land that touched the borders of their realm. The people who lived there were mostly accustomed to it, and took all sensible precautions, but the reputation of the place was such that most folk from other lands avoided it. So when the news came that a troupe of entertainers were coming to the village, well, everyone for miles around resolved to make the trip to town. Jazeret’s father, who did not trust towns, refused permission for her to go. She begged and wheedled and cajoled but all in vain. She was forced to listen to her friends tell stories about the tents going up and the show that would be put on and the treats to be purchased and know that this would all happen without her. When, at last, the night of the great event came, she was resolved to be there. So she told her mother she was going to look for mushrooms in the woods and, once out of sight of the house, ran down the road towards the town.

“Now the town was some distance away and Jazeret could hardly run all that way, so it was twilight and she was footsore and tired by the time she rounded the last bend in the road. There, she stood still, for she could hear the music and laughter from the village green, and see the great white tent glowing in the moonlight. It was so beautiful that she found her strength again and ran the rest of the way into town.

“The green was crowded with people. They were a smiling, laughing, joyous whirlpool that sucked her in and spun her round through all the delights of the fair; the apples coated in syrup, the fortune-teller who promised love for a coin, the jugglers and acrobats. Then she was whirled into the tent and the greatest wonders of all: the beautiful, foreign women who stood on the backs of white horses as they pranced around the ring, the lithe and graceful men who leapt and twisted from ropes, the sinuous, eerie twisting of the contortionist. In the end, Jazeret was breathless with enchantment.

“Outside, in the cool evening air, her mind was still awhirl with colour and spectacle. With all that dazzle in her eyes, she did not see the young man until she stumbled into him. Then she did—and he was dazzling too. ‘Hello,’ he said. ‘My name is Tam.’

“Love can strike like lightning, so they say, and it struck Jazeret right then and there. It struck Tam, too, for lightning, while not always fair, is sometimes kind. Being young, and lightning-struck, they drifted through the rest of the fair in a dream and drifted into the darkness as the townspeople slipped home to their beds and the troupe closed the curtains on their gaiety. In the darkness, they pledged their love and sealed it and made the vows that lovers do, when lightning strikes them.

“But in the hour before the dawn, when it was still night but only barely, Tam told her that he could not stay. She wept and begged and cursed him. ‘What can I do to hold you here?’ she asked.

“‘I would stay, if I had will in this. But I do not. For I must be home before dawn or face my lady’s wrath.’

“‘And who is your lady,’ Jazeret asked angrily, ‘that you must fear her wrath? Who is she that you love more than me?’

“‘Not more than you,’ he promised. ‘But I am bound and I must go.’

“‘When will I see you again?’

“‘Never,’ he said and turned away. But he turned back and dropped to his knees beside her and whispered, ‘Be at the crossroads as the dawn comes. If your love is true, then claim me.’

“Then he was gone and Jazeret sat alone and thought on what he had said.

“At dawn, she was at the crossroads, sitting on a log by the side of the road. At the first touch of light in the eastern sky, she heard bells and horses’ hooves. The air was full of perfume, sweet and cloying, and she was suddenly afraid.

“They came out of the east, riding away from the dawn. She saw the foreign women and the graceful men and the slant-eyed contortionist. In the centre of them was a bone-white horse and, on its back, a woman it hurt Jazeret’s eyes to look upon. Behind her, on a horse as black as night, was Tam.

“I cannot, she thought, as they drew closer.

“But when they drew near, she stepped onto the road. No heads turned, no horses slowed. Jazeret breathed, the air hot and burning in her mouth, and waited for Tam. When he passed, she put her hand on his ankle and said, in a loud, trembling voice, ‘I claim you.’

There were no bells then but thunder and the world went black around her and the perfume changed to the scent of carrion. ‘If you claim,’ said a voice as cold as ice, ’you must hold.’

“Jazeret gripped Tam’s ankle in both hands. ‘I will hold.’

“The shape in her hands changed, no longer cloth and flesh but cold scales and heavy muscle. Something hissed in her face but she did not let go. Then her hands were full of fur and claws and a roar rocked her backwards but she did not let go. Feathers and thorns and fire all shaped themselves in her grip. She felt as if her skin were melting, her bones breaking.

“But she did not let go.

“At last, the cold voice said, ‘Enough.’ Then the thing in her hands was another human hand and she opened her eyes to see Tam’s face. ‘Have him, if you will. Though wanting is always better.’

“The voice echoed for a moment then was gone. The sun broke over the horizon and Jazeret saw that the road was empty but for her and Tam.

“And there they lived till the end of their days, in the land on the border, in the place that is not here and a time that is not now.”

With the final, traditional phrase, Vash bowed to the assembly. As the cheers arose, Lilit heard the woman beside her snort in disgust.

“Didn’t you like it?” she asked, glancing at her neighbor, a woman a few years her senior.

“Oh, Vash tells it well enough,” the woman said, gathering herself up to leave. “But the ending’s wrong.”

“Why?”

The woman looked at her. “Because it’s happy.” She read Lilit’s confusion on her face. “Don’t they teach you children anything anymore? With them, there are no happy endings.”

Excerpted from Cold Hillside © Nancy Baker, 2014