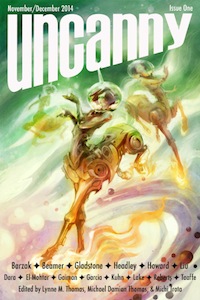

Welcome to Rich and Strange, a weekly spotlight on short fiction I’ve thoroughly enjoyed! This week I want to look Maria Dahvana Headley’s “If You Were a Tiger, I’d Have to Wear White,” appearing in the inaugural issue of Uncanny Magazine.

It’s occurred to me that, given the permeable nature of professional relationships in our genre, I might change the name of this column to Full Disclosure, since I’m often hard put to find stories I love written by people or appearing in venues to which I have absolutely no connection. It’s a natural state of affairs in genre that we read a thing we love, meet the person who wrote it at a convention, strike up an acquaintanceship that becomes a friendship, and then find that we’re reading the excellent work of people we now chat with on a regular basis. So it goes – but I’ll always state those connections up front when they occur.

So for instance, this week in Full Disclosure, I reveal that I read “If You Were a Tiger, I’d Have to Wear White” for Uncanny’s podcast (and was paid to do so); that I supported Uncanny’s Kickstarter; and that Headley once bought me a salad at Readercon. Personally what I think you should take away from this is that I loved “If You Were a Tiger, I’d Have to Wear White” enough to tediously itemize the above because as we all know it’s actually about ethics in short fiction journalism.

“If You Were a Tiger, I’d Have to Wear White” begins in the late ‘60s. Mitchell Travene, reporter for a men’s magazine, has been commissioned to write a piece about Jungleland, the animal theme park and training facility in Thousand Oaks—except in this world, the animal actors are sentient, speak, and perform Shakespeare and Chekhov. By the time Travene comes around, however, Jungleland is bankrupt and on the cusp of closing, a fading echo of its glory days. “The magazine,” says Travene, “was looking for an article one part cult massacre, one part Barnum, but above all, they were looking to profile the Forever Roar, who’d remained mum for the past twenty years.” The Forever Roar is, of course, Leo the Lion from the Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer opening sequence.

The place was a Sunset Boulevard of drunken rages, drownings in the pools, and a herd of gazelles who refused to change out of their pajamas. The day I arrived, I glimpsed a fretful chimpanzee who’d played opposite both Tarzan and Jungle Jim and now spent all her time dressing up in old feathers. She swung naked into a plaster tree and was gone before I could ask for an interview.

The leopards were using heroin and even the ostriches, traditionally abstemious, were drunk. A cancerous camel strutted the perimeter, spitting tobacco juice. The residents were lonely in their various sections of the park, all of them stretched on old recliners in their terrycloth robes, drinking forlornly from bottles and bent tin dishes.

Spurned by Leo for an interview, Travene turns to Mabel Stark, 80-year-old tiger trainer and one-time double for Mae West in I’m No Angel, for salacious details about Jungleland and its residents—and gets far more from her than he bargained for.

This story is pitch-perfect where tone, voice, and setting are concerned; reading it I felt awash in the kind of California sunlight that feels grim and desolate in its inescapability. The story’s pace is a beautiful thing, too, a slow unfolding of narrative sleaze running parallel to an urgently building emotional crest. Like a film from the classic period it portrays, it’s a story both coy and breathtakingly passionate, wringing wonder from bleak, drab despair. There’s magic in the fade of diamante, in the reduction from main-stage to side-show, in going from riches to rags, and Headley captures that mixture of self-destructing desperation perfectly. I was reminded, throughout, of Rich Koslowski’s Three Fingers, and occasionally of Who Framed Roger Rabbit. I’m fascinated by stories that are fascinated by Hollywood; it is, itself, such an unlikely institution with such a rapacious history that reading fiction about it feels like watching a snake devour its own tail, or holding up mirrors in a funhouse full of them. I want to write a whole other essay, in fact, on the representations of exploitation in fictions about Hollywood: I find myself wondering about the politics of presenting cartoons and animals as sentient actors more vulnerable to exploitation than their human counterparts, because I wonder who that elides historically, especially where race is concerned.

But I didn’t see ham-handed metaphors for race in Headley’s story; I saw the tale type of beastly bridegrooms twisted out of its usual setting of European fairy tale and into the American fairy-tale-in-reverse that is Hollywood. If traditional fairy tales end in marriage and the achievement of riches, stories about Hollywood feel inevitably about the loss of fame, fortune, dignity, and a sort of godhood sacrificed to the institution that made it possible in the first place. It’s gorgeous, clever, wry, and utterly self-aware.

But possibly more remarkable than the meticulous crafting of “If You Were a Tiger” is how much of it is factually true. Jungleland was a real place; Mabel Stark was a real person; the photograph of Clark Gable holding lion cubs is real. This was a story that had me falling down the Wiki-hole in search of photos and soundbytes from Stark, details about Garbo’s life and loves. It takes a deft hand to balance the stranger-than-fiction with strange fiction, and Headley succeeds admirably.

Headley’s story oozes doomed glamour and hopeless nostalgia in ways that I found disquietingly riveting. It’s a fitting launch-point for a magazine called Uncanny.

Amal El-Mohtar is the author of The Honey Month, a collection of stories and poems written to the taste of 28 different kinds of honey. She has twice received the Rhysling award for best short poem, and her short story “The Green Book” was nominated for a Nebula award. Her work has most recently appeared in Lightspeed magazine’s special “Women Destroy Science Fiction” issue, Kaleidoscope: Diverse YA Science Fiction and Fantasy, and in Uncanny. She also edits Goblin Fruit, an online quarterly dedicated to fantastical poetry. Follow her on Twitter.