Welcome back to The Pop Quiz at the End of the Universe, a recurring series here on Tor.com featuring some of our favorite science fiction and fantasy authors, artists, and others!

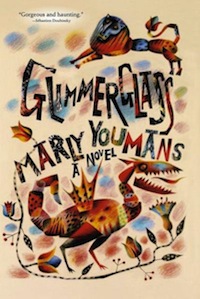

Today we’re joined by Marly Youmans, award-winning poet, novelist and short story writer. A native of the Carolinas, Youmans now lives near the mouth of the Susquehanna with her husband and three children. Her latest novel, Glimmerglass, is a stylish, contemporary variation on the Bluebeard legend.

Join us!

What is your favorite short story?

This morning it is Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “Gimpel the Fool.” The story is wonderfully made and packed with soul and heart. Tomorrow it might be something else.

Describe your favorite place to write.

Describe your favorite place to write.

The just-released Glimmerglass was written all over the house, indoors and out. That’s the pleasant part of having a laptop (the unpleasant part came on a sad day last week when my macbook died.) I’m not fussy about a place to work—I don’t have a lucky pen or need my chair in proper alignment or insist on utter silence, though I find those sorts of minor obsessions interesting in others. When my writing room is not a tornado of paper and a foot-tangling mess of books, I’m quite happy working there. It’s fairly much the expected, a writing table and loaded bookshelves and stacks of manuscripts. Art by friends hangs on the walls, but I don’t notice the surroundings when I’m writing. I have a window and occasionally focus on the distant landscape to avoid completely ruining my near-sighted eyes. Outside is a view of trees and Otsego Lake (the lake James Fenimore Cooper called Glimmerglass in the Leatherstocking tales), with the tiny castle of Kingfisher Tower floating on the water and Lion Mountain in the distance. The scene reminds me how weird and magical and touched by storytelling the world is.

Please relate one fact about yourself that has never appeared anywhere else in print or on the internet.

Writers are not that exciting—they’re busy sitting in pokey corners, heads buzzing. And I’ve already admitted to my wacky features… My first step was at 17 months, though I was talking in little paragraphs before I turned one. Clearly I was doomed to be a writer who has to be dragged into exercise. But I could have been a dietician because I was the uncredited inventor of the Paleo diet—I would only eat raw foods and so became a toddler with a carotene flush to her face. Maybe I could have been a great sportsman because I caught a gigantic alligator snapping turtle at False River when I was four or five. I could have been known for overcoming handicaps, since my Yankee sixth-grade teacher thought I was mentally retarded due to my deep-South drawl. (I used that sad-and-comic detail in A Death at the White Camellia Orphanage.) I’ve probably mentioned all those sorts of things in interviews.

But I haven’t talked about an important source of outrageous stories, so perhaps that ought to be my until-now-withheld fact. I suspect that the strangest and most hair-raising element in my life is Michael, though I don’t deserve any credit for his wildness. I’m married to a man who accidentally and innocently became engaged to a doctor while volunteering in Vietnam, who made his Egyptian guide angry by winning a race on horseback to the pyramids at Giza (a few hours before riots broke out—Michael likes to keep things lively), who almost starved to death in the snowy Himalayas because his insides couldn’t bear the diet of mutton fat plus sardines in tea, who slept curled in a bloody sheepskin on a ledge in the Crazy Mountains (I call that a grizzly wrap, or maybe shades of Star Wars), etcetera. And I do mean etcetera! Michael’s ability to become entangled in a story on the other side of the world—to leap into the unknown with strangers and yet come home safely—beats anything made up. Life is frisky and unexpected with him.

Do you have a favorite unknown writer?

As I write and read poetry as well as fiction, I am frequently wandering territories of the less-known, and it is in the land of poetry where you find the most radical obscurity, the most unknown unknowns. I’m fond of the late poets Charles Causley and Kathleen Raine, who are known in the U.K. but aren’t read much in this country. Causley loved stories and ballads and folk materials, clicked words together beautifully, and could be frolicsome and fantastical. Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin admired him. Kathleen Raine was a self-proclaimed follower of Blake and Yeats. She belongs in the company of poets who think that poetry should approach song. Thomas Disch wrote a good introduction to her work that’s in The Castle of Indolence, his collection of reviews and essays about poetry.

Recently I read with poet Luisa Igloria in Norfolk, Virginia, and I recommend her—a look at her poem-a-day project can be had at Dave Bonta’s Via Negativa, and she has several brand new books, Night Willow (prose poems from Phoenicia Publishing in Montreal, a small press that also published my post-apocalyptic blank verse poem, Thaliad) and Ode to the Heart Smaller than a Pencil Eraser, which won the May Sarton award.

Here’s a sample from Luisa’s prose poems:

“Foster”

Who’s to say what you can believe or not? For every animal of affection that walks into your ark, its snarling twin pulls at the chains, trembles the floorboards. You feed them both, you give the same milk and the same bone wrapped in meat, hunks of bread to sop up the oil and broth. In the dark, it’s hard to tell one from the other. Their eyes have the same marble sheen, obsidian or clear grey flecked with green. One will tolerate the length of the journey. The other will pace and pace, howl at the moon, the rain, the sun, its shadow. You know it could tear you to pieces if you gave it more than a chance. But you sing to both, you run your hands through their sorrowful pelt: this one thing they let you do without complaint, knowing you too must live in your skin.

And if you still want some fiction that tilts toward the fantastic, Leena Krohn’s Tainaron was the first to pop into my head when I looked at the question. For an unknown-in-this-country book for younger readers, I would pick Leon Garfield’s marvelous Smith. It’s a good crossover book—at least, I find it interesting, and it is full of wonderfully strange descriptions. Many books are called Dickensian, but Smith actually is Dickensian (in a Garfieldian way.)

What’s the best Halloween costume you’ve ever worn?

My favorite costume as a child may have been a homemade Mad Hatter costume. The hat came down past my knees, so no doubt I was a bumpy danger to myself and others. I read and reread the Alice books many times, so the Hatter was a natural choice. “We can’t all be Mad Hatters,” says Diana Wynne Jones’s Howl. But sometimes we can.

My subsequent adventures in costume have been to assist three children in their shenanigans. We are guilty of having an enormous dress-up box that has dressed dozens of children at birthday parties and Halloween.

Strangest thing you’ve learned while researching a book?

I live in a house built by a writer (Colonel Prentiss’s newspaper is still in print) in 1808. It’s a straightforward federal center-hall house, and it would appear to have few secrets. But if I dig in the garden, I find a Dutch pipe or a clay marble or shards of transfer-ware. Concealment shoes (meant to kick witches out of the house) were hidden in one of the chimneys. It’s the same way with peering back into time; surprise is everywhere. The main thing I’ve learned through historical research is that nothing is as they tell us in history books. Nothing is generalized, and everything is specific and strange and not at all simple because people are individuals and the rules for life change. When I was researching American slavery, I ended up reading about all sorts of oddities—the freedmen who owned slaves, the occasional white slave, peculiar punishments, holes in the ground for singing-into, etc. When reading Scots-Irish lore for two books set in the Carolina mountains, I was surprised by (and then used) beliefs having to do with witchmasters. Research is enticing because it steers in unexpected directions, yet also functions as a temptress who can lead a writer into the drear realm of info-dumps. But we don’t have to tell everything we know…