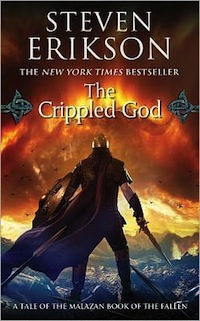

Welcome to the Malazan Reread of the Fallen! Every post will start off with a summary of events, followed by reaction and commentary by your hosts Bill and Amanda (with Amanda, new to the series, going first), and finally comments from Tor.com readers. In this article, we’ll cover part one of chapter twenty-four of The Crippled God.

A fair warning before we get started: We’ll be discussing both novel and whole-series themes, narrative arcs that run across the entire series, and foreshadowing.

Note: The summary of events will be free of major spoilers and we’re going to try keeping the reader comments the same. A spoiler thread has been set up for outright Malazan spoiler discussion.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

SCENE ONE

Banaschar recalls an earlier scene in Tavore’s tent and Tavore’s words to Lostara:

It is not enough to wish for a better world for the children. It is not enough to shield them with ease and comfort. Lostara Yil, if we do not sacrifice our own ease, our own comfort, to make the future world a better one, then we curse our own children. We leave them a misery they do not deserve; we leave them a host of lessons unlearned. I am no mother, but I need only look at Hanavat to find the strength I need.

Banaschar was thrown by those words. After Lostara leaves, he tells Tavore he has stopped running. She asks him what D’rek wants, why she is “so determined to be here” and if she will oppose the Adjunct. He tells her D’rek will “protect it,” agreeing when Tavore tells him that might kill D’rek. When she says his god believes they will succeed, he tells her D’rek does not care “if the Crippled God is whole or not… Whatever you have of him, she wants it gone,” adding he thinks, “His god has lost all faith.” She tells him “they won’t fail,” refusing to accept Banaschar’s advice that they have to plan on the likelihood of failure. At the end of their conversation, he says perhaps then they will teach his god a “lesson in faith.” He, Tavore, and Fiddler ride out of camp to the northwest.

SCENE TWO

They ride through the night to a singular rise past ancient camps. Banaschar thinks how:

It all passes. All our ways of doing things… these lost ways of living. And yet, could I step back into that age… I would be no different—no different inside… Our worlds are so small. They only feel endless because our minds can gather thousands of them all at once. But if we stop moving… each one is the same. Barring a few details. Lost ages are neither more nor less profound than the one we live in right now. We think it’s all some kind of forward momentum, endlessly leaving behind and reaching towards. But the truth is… we do little more than walk in circles.

They dismount at the hill and climb it. Fiddler says it will do. At the top, they discover a ring of boulders and thousands of unbroken flint spear points. Banaschar wonders why they were left, and theorizes the builders had discovered a technology that was too successful, leading to killing the animals to extinction, “because we are all equally stupid, just as shortsighted, twenty-thousand years ago or tomorrow… The seduction of slaughter is like a fever.” He adds when they realized what they’d done, the builders had blamed their tools rather than themselves, saying, “even to this day we think efficiency’s a good thing.” Fiddler replies that he wonders if humanity invented war only when it ran out of animals to kill. Banaschar asks why they’re here, and Fiddler answers because it is defensible. Tavore asks about D’rek, and the priest says perhaps she can wrap around the based of the hill to contain whatever. Tavore draws her otataral sword and Banaschar says, “It shall summon.” She sticks it in the ground, then faints.

SCENE THREE

Banaschar tends Tavore while Fiddler breaks up his Deck of Dragons, burning it to cook Tavore a hot meal. Banaschar says it seems Fiddler doesn’t expect to survive, but Fiddler says even if he does, he will retire and take up pier fishing. Banaschar talks of his entry into the priesthood and realizing it was the wrong place for him, and Fiddler recalls a friend trying to convince him to stay out of soldiering. He says though that the best anyone can do is show someone options; they can’t direct a person down a particular path. Tavore wakes and tells them they have to get going. When Fiddler says after they eat, she asks if he knows who her sword is summoning. His answer, “Aye, just burned that card,” shocks her momentarily speechless. When she says he shouldn’t have burned his Deck, he replies he saved the only House that means anything. When she says their House is still divided, he tells her not to worry—the King in Chains is “too busy undermining the throne he happens to be sitting on” and the Knight is with them. She says when the god of war manifests, it will he huge, feeding on the souls of thousands on the battlefield. He tells her not to worry and to eat, listing those that are with them: Reaver, Fool, the seven, Leper, Cripple (he looks at Banaschar when he says that one, and the priest thinks, “well, [that’s] been staring me in the face all this time”). Tavore asks Banaschar if he was the one who took off her helmet and combed her hair, and when he says yes, she apologies for looking such a mess.

SCENE FOUR

Watching the three return to camp, Hedge orders Bavedict to distribute all the munitions and get their group ready. He then tells Fiddler he and his Bridgeburners are going with him. When Fiddler refuses, Hedge explains he’s already talked to Tavore, adding that Fiddler needs him there and if he doesn’t let him go, Fiddler will spend the rest of his life full of regret. Fiddler yells that his group are not Bridgeburners: “It’s not just a fucking name! You can’t just pick up any old useless fools and call them Bridgeburners!” But Hedge asks why not, saying they were young and stupid and wanting to be better than they were when they started out. Crying, Fiddler tells him again not to come, but Hedge says he has no choice. Fiddler leaves.

SCENE FIVE

Alone, Fiddler weeps, thinking, “We’re going to die—can’t he see that? I can’t lose him again—I just can’t.” He gets hold of himself, driving the anguish away, thinking:

[O]ne more thing to do, and then we’ll be done. All of it, finished. Gods, Hedge, we should have died in the tunnels. So much easier, so much quicker. No time to grieve, no time for the scars to get so thick it’s almost impossible to feel anything at all. And then you showed up and tore them all open again. Whiskeyjack, Kalam, Trotts—they’re gone. Why didn’t you stay there with them? Why couldn’t you just have waited for me… End this. One more thing to do… I need to be a captain, the one in charge. The one to tell my soldiers where to die.

He heads toward his group.

SCENE SIX

Corabb tells the group they are all his family today, as they are going to fight. Tarr arrives and tells them to get ready to leave, adding they are going a different place than the regulars and implying they aren’t coming back. Corabb thinks he sees fear in Smiles, and he thinks how young she is. He says she will stand beside him, then mentions her hair makes her look “almost pretty.”

SCENE SEVEN

Fiddler leads the marines and heavies out down the central aisle of camp, and the regulars form to the side, lining the route but saying nothing. Cuttle is unnerved at the silence, and at how old the regulars look, though he thinks his group must look the same, and he wonders what the regulars are thinking/seeing as they watch them pass. He wonders too if the regulars have figured it out, that they’re heading to face an Assail army down to buy time, and doing so without the heavies or marines. His anger grows as he assumes the regulars must be thinking his group is abandoning them. But then the regulars begin to salute fists to chest. He walks with Balm beside him and thinks, “This is what the Adjunct said wouldn’t happen. Look at these regulars. They’re witnessing us.”

SCENE EIGHT

Kisswhere asks if Sinter has seen any of this, of the future, in her visions, but Sinter says her visions aren’t like that. When Kisswhere says it doesn’t matter; she can see easily enough where they’re heading, Sinter tells her it’s just the fear talking. Kisswhere gives Sinter her “vision” of the future, with she and her sister having kids and husbands and a normal life.

SCENE NINE

Hellian recalls her first time having sex, and how the boy had been killed a year later in his father’s shop. She thinks how glad she is that the boy at least had sex before he died, and how “it’s not fair, how the years just vanish.”

SCENE TEN

Urb thinks of how hard it can be to tell Helian he loves her. He wishes he could make love with her, hold her in his arms before he dies, make everything perfect and see it in her eyes.

SCENE ELEVEN

Widdershins walks beside Throatslitter and recalls the first officers he’d met, complaining about their soldiers. He thinks perhaps the Bridgeburners had been both the “worst of the lot, but they’d also been the best, too,” and he likes that the Bonehunters are “in the tradition of their unruly predecessors.”

SCENE TWELVE

Deadsmell marches behind Throatslitter, feeling the Bonehunters were nearing the end, and recalling all they’d done:

We marched across half a world. We chased a Whirlwind. We walked out of a burning city. We stood against our own in Malaz City. We took down the Letherii Empire, held off the Nah-Ruk. We crossed a desert that couldn’t be crossed. Not I know how the Bridgeburners must have felt, as the last of them was torn down, crushed underfoot. All that history, vanishing, soaking red into the earth. Back home… we’re already lost. Just one more army struck off the ledgers. And this is how things pass… I don’t want to say goodbye. And I want to hear Throatslitter manic laugh. I want to hear it again and again, and for ever more.

SCENE THIRTEEN

Hedge stands with Rumjugs and his group watching the marines and heavies approach. When she asks who he thinks gave the order for the parade salutes, he tells her nobody: “This came from somewhere else. From the regulars themselves.” He notices that Fiddler looks “as bad off as the rest of them. Like you’re headed for the executioner.” He notes as well that the Bridgeburners hadn’t expected the salute and hadn’t known how to handle it:

Us soldiers only got one kind of coin worth anything, and it’s called respect. And we hoard it, we hide it away, and there ain’t nobody who’d call us generous… But there’s something feels even worse than having to give up a coin—it’s when somebody steps up and tosses one back at us. We get antsy. We look away. And part of us feels like breaking inside, and we get down on ourselves. Outsider don’t understand that… It’s because of all the friends we left behind, on all those battlefields, because we know that they’re the ones deserving of all that respect… Some riches stick in the throat, and choke us going down.

Hedge tells Fiddler to turn his company back to face the regulars and give them “the coin,” back. When Fiddler hesitates, Hedge asks if it’s because he doesn’t think the regulars are worth it. Fiddler doesn’t answer, and Hedge says he and Fiddler aren’t made for this sort of thing, and he just thinks what Whiskeyjack would do in situations. He says Fiddler needs the regulars to buy time, and so even if he doesn’t think they deserve it, he has to give the coin back. Fiddler agrees, saying he “just faltered a step.” Before they turn back, Fiddler says everyone needs to see one more thing, and he holds out his hand for Hedge to take, then the two embrace.

SCENE FOURTEEN

Saddic asks Badalle what’s happening, and she tells him, “Wounds take time to heal,” saying Fiddler and Hedge are “brothers.” When Saddic asks why she calls Fiddler “Father,” she answers that “It’s what being a soldier is all about… You do not choose your family, and sometimes there’s trouble in that family, but you do not choose… They come face to face with death, Saddic. That is the blood tie, and it makes a knot not even dying can cut.” She adds that soon this family will, “awaken to anger.” He asks if they’ll ever see the marines and heavies again, and she tells him it’s simple, “just close your eyes.”

SCENE FIFTEEN

Pores watches the embrace from the edge of camp, noticing that neither Tavore nor Blistig are visible. Faradan Sort and Kindly join him, and he and Kindly do their thing until Faradan tells them to shut up, as they’re about to be saluted. The marines and heavies do just that, and Kindly offers up a history of the “coin thing,” before rhapsodizing over the Seti combs. Pores asks what Kindly needs him to do, and is shocked when Kindly lays a hand on his shoulder and tells him he has no order for Pores. When Kindly leaves, Faradan tells Pores, that, “If he had a son to choose, Pores… He was saying goodbye.” Pores says he knows that, grateful for the physical pain that “keep [s] the other kind at bay.” Faradan tells him the battle will be soon, and he wonders then where the marines and heavies are going. He asks her if the regulars will fight, and she tells him not another word about that, then leaves. Pores thinks he might need to deal with Blistig, whom he assumes won’t be any good in the fight anyway.

SCENE SIXTEEN

Lostara summons Blistig to Tavore’s tent. Passing through the regulars, he thinks they look “fragile,” and he believes they’ll melt at the first trouble. When Tavore gives him the battle plans, he tells her there’ll be no battle; it’ll be a rout, since without Tavore’s sword, the FA’s sorcery will just overwhelm them. She ignores him, telling him he’ll be in the center and will face the Kolansii and that he mustn’t yield at all. He considers then rejects killing her, then says he’ll get stabbed in the back by his own soldiers before they even see the opponent. She tells him she was advised way back in Aren to leave him in command of the city garrison or promoting him to city Fist, which might have led to him being High Fist of all South Seven Cities, a role that would have suited him “perfectly.” But, she goes on, those advising her couldn’t see past their own city walls, couldn’t imagine Mallick Rel’s rise, his infiltration of the Claw, or that Rel’s hatred of Blistig for his “betrayal” at Aren meant that Blistig would have been assassinated. She tells him in fact people died saving him from several such attempts. She explains she saved him not for his command value, though she respects that, but because Rel and Dom would try to rewrite history with regard to Aren, the Wickans, the Chain, and so she needed to keep Blistig alive to keep the truth alive. He tells her again the soldiers won’t follow him, but she says they will, as they will have no one else, because she will be fighting the sorcery of the FA. He notes she will fail, and such a plan only works if she can take the FA down with her. He wonders how they’ll hold the army together with her dead, and tells him again to hold the line, or at least, to “take a long time dying.” He leaves, wondering who had stopped three attempts on his life by a claw.

SCENE SEVENTEEN

Lostara brings Banaschar to a meeting with the officers, including Skanarow, Ruthan Gudd, and Faradan Sort. They want to know how Tavore will defend herself against the FA without her sword, and he tells them he has no idea. Lostara says she doesn’t think she’ll be able to Shadow Dance as she had before. Banaschar asks Ruthan Gudd if the Stormrider power will rise again in him, and Gudd says Tavore thinks it will, but it’s “complicated.” When Banaschar asks if the Stormriders didn’t give him the gift for this moment, Gudd tells him “nobody is as forthcoming on these things as one might like,” admitting they probably knew what was in Kolanse, but wonders if they are interested in “liberation.” Sort says, “hardly,” and he when Ruthan Gudd says he had suspected she had good reason for leaving the Wall, she tells him she fought nearby Greymane. Lostara asks if Gudd is afraid of using the power, but Banaschar explains that Gudd thinks that if the Stormrider power wakens, it will “conclude that said risk is too great—with too much to lose should the Adjunct’s plan fail.” When Lostara asks if Gudd doesn’t control his own power, he wonder the same about her and her Dance. She replies that’s the will of a god, but he asks if she even knows whom the Stormriders serve? The others decide they need to get their troops ready and leave Lostara, Banaschar, and Gudd alone. Lostara tells them Cotillion swore he would not possess again, and Gudd admits he’s now beginning to wonder if he’ll survive what’s coming. He asks Banaschar what his reason is for being there, and where he’ll be, if it won’t be beside Tavore. Banaschar answers he’s been haunted by that same question, and wonders too, “How does a mortal win over a god? Has it ever happened before? Has the old order been overturned? Or is this just special circumstance? A moment unique in history?” Gudd is shocked at the idea that D’rek might be on their side, but Banaschar says he wasn’t speaking of his power; he was referring to Tavore: “She simply refused to waver from her path, and by that alone, she has humbled the gods. Do you understand me? Humbled them.” Gudd says the gods are too arrogant, and Banaschar replies he once thought so too, before asking Gudd if he will fight for Tavore. Gudd replies, “With all my heart.”

SCENE EIGHTEEN

Tavore mounts up and moves to the front of the column amidst silence, “And of all the journeys she had undertaken, since the very beginning, this one—from the back of the column to its head, was the longest one she had ever travelled. And, as ever, she travelled it alone.”

Amanda’s Reaction

These words that Tavore says to Lostara, regarding the legacy that they leave for children, is an idea that sounds as if it might be incredibly personal to Erikson, because the words ring with utter truth and sincerity:

“It is not enough to wish for a better world for the children. It is not enough to shield them with ease and comfort. Lostara Yil, if we do not sacrifice our own ease, our own comfort, to make the future’s world a better one, then we curse our own children. We leave them a misery they do not deserve; we leave them a host of lessons unearned.”

I think, as a generation, this should be behind all of our thoughts on climate change and matters like that. We shouldn’t be thinking about what it costs us, or whether it is true or not—we should be considering the legacy we are now leaving for those who come after us and will suffer for the excesses that we have consumed.

I never ever made the connection that the Snake was a manifestation of D’rek. Does this perhaps show that D’rek is operating to assist the Bonehunters? Since the Snake arrived at pretty much the point that they were giving up and imploding as an army?

It’s an odd position for us readers to have more information than Tavore (about what is happening to the heart). I rather like this position. I am being all smug. Towards a fictional character. Hmm. I don’t think this makes me the winner!

Oh, both sadness and pride when seeing this exchange:

“They are led by Gesler and Stormy, Banaschar.”

“Gods below! Just how much faith have you placed in the efforts of two demoted marines?”

She met his eyes unflinching. “All that I need to.”

I’m a little unsure about this scene—did they take themselves away from the army in order that Tavore could earth the Otataral sword in a place of their choosing? Or does she bury the sword when they realise it has come to life? I’m curious because the former would mean that they are aware of the dragon able to sniff this out. Are they planning to use her somehow?

Ah, this wonderful tribute to Fiddler from Banaschar:

“The soldier might as well have said, ‘We’re laying siege to the moon,’ and been absolutely convinced that he would do just that, and then take the damned thing down in ruin and flames.”

Feels like a little call back to Gardens of the Moon as well.

I do like the idea of gardening as just another war, except a fight against the Earth to grow what you want to and not what it wants to.

And then what a beautiful thought: “We should all live a life of hobbies. Doing only what gives us pleasure, only what rewards us in secret, private ways.” I am blessed to be living that life right now, and it gives a different meaning to waking up every day.

It is odd seeing Tavore talking about events that we have already seen—here, the god Fener manifesting above the battlefield. Confirmation here of the Knight being Karsa, the Cripple being Banaschar and the Consort being Tavore (of the House of Chains).

And that touching moment where Tavore worries about looking like a mess. Somehow, that choked me up.

More anguish when we see Fiddler dealing with Hedge so harshly, and knowing that it comes from a fear of watching him die again and being without him again. And then that dry and bitter understatement from this hoary old hero: “Let’s just call it a bad day and be done with it.”

Oh, this salute, this witnessing of the regulars to the marines—it’s just wonderful. Glimpsing into the minds of these beloved characters, seeing their thoughts about the tribute being paid them, knowing that these guys are relying on the regulars to slow down the army that is coming for them so that they can achieve what they have to.

And then this:

“We marched across half a world. We chased a Whirlwind. We walked out of a burning city. We stood against our own in Malaz City. We took down the Letherii Empire, held off the Nah’ruk. We crossed a desert that couldn’t be crossed.”

You know how we all felt about the Bridgeburners? And how some of us almost resented this Bonehunter army, since they couldn’t possibly replace what had been stolen from us? (I did, anyway) And now, here we are, with the Bonehunters taking their place in legend, witnessed or no. It’s stunning. And it takes my breath away realising how this affection and respect and regard has grown up over books and books for these troops heading to their final battle.

I appear to have dust in my eye as I read this section with Fiddler and Hedge…

We’re being told or suggested from a few quarters now that the regulars aren’t likely to fight very hard, that they just don’t have the will. I wonder which way this will go—either Erikson will turn it on its head and give us a fist in the air moment as they discover their backbones, or those people will be proved right and the regulars will fold faster than a bad hand in poker.

There is a chasm of difference between that salute between the soldiers and Blistig’s view of them:

“One final sacrifice to defend an army that doesn’t even like you? That doesn’t want to be here? That doesn’t even know what’s it’s supposed to be fighting for?”

Seeing those words, and comparing them to the silent tribute between regulars and marines just seems a world apart.

Oh Tavore. From the way that Banaschar tells the others that she has humbled the gods, to the threadbare clothes she now wears, to the lonely journey she travels to the head of the column… she is an utter enigma, and yet I remain transfixed by her.

Bill’s Reaction

A lot of emotion in this chapter, as our characters, at the start, prepare themselves, many of them for what they assume will be their last day or two alive.

I think Tavore’s words to Lostara that Banaschar recalls speak to something that has driven Tavore—that what I’ve been referring to as the twin cores of this series, empathy and compassion, are not enough in and of themselves. They are instead mere starting points, and one comes from them then is the understanding of the need to sacrifice for others (especially the children) and the willingness to do so. Without that willingness, those emotional responses are nice enough, but what do they matter if one becomes part of the world’s horrors, but simply feels bad about them?

It’s interesting that Banaschar is so disturbed by these words, and wonders too what still lies beneath Tavore’s compassion, her drive, her willingness to sacrifice herself (and others), asking himself, “How many great compassions arose from a dark source? A private place of secret failings?” Is there something in Tavore’s childhood we don’t know about? Something we will ever learn of? Is this a reference to what she had to do to her sister—send her off (even though she tried to protect her)? Is that the “darkness”? The failure? Or could it even be a reference to one of the more horrible possibilities, that Tavore knows she killed her sister way back, which would certainly qualify as a “dark source.”

Tavore’s linking of the snake to D’rek is interesting, though to be honest, I can’t say I fully get it. I’m not quite sure who the “children” of D’rek were. Possibly a reference to her priests from way back, who had been “lost” and so were killed by her, leaving her without adherents (save Banaschar) and so lost herself. Or perhaps the children of the Snake were a manifestation of her children because they were dying in such numbers? That seems to be a bit of the implication with the line, “they’re just children now.” That maybe in their dire straits they became more than just children, they manifested D’rek (which would explain some of their travel through warrens, Badalle’s abilities, perhaps), and now D’rek is here and obviously going to be a big part of the ending.

I wonder how differently this scene would read had we not already seen what happened back at the Spire. Still, nice to see Tavore’s faith, knowing it has been met.

We’ve had this reference to humanity walking in circles before, this concept of never having gained much wisdom despite our attempts to delude ourselves otherwise, and it’s certainly appropriate that this idea gets raised again here at the end. Will the circle be broken perhaps, a little at least, by what is intended here?

More echoes—this theme of extinction, and the idea that once the animals are gone, humanity will turn on itself, or as Fiddler says, was forced to invent warfare to take the place of all the killing we had done of the animals.

I like that little detail of the spear point breaking in half when Tavore drops it.

Well, we all know who’s coming for the sword, right?

That’s a lovely moment, Banaschar tending to Tavore, Fiddler burning his Deck (all but the House of Chains), talking about retirement and fishing. A lovely intimate human moment amongst all this fear and anguish. And I find its end, Tavore’s concern about her looks, and the two men’s response to that concern, to be quietly, softly moving.

From a quietly fraught scene to a loudly fraught one between Fiddler and Hedge. Did anyone have any other thought that Fiddler was acting the way he was beside the fear of losing Hedge again, the sense of impending loss all over? It’s a great short scene I think for knowing (if one thinks this) that, and luckily Erikson makes sure to make that reason clear immediately afterward rather than delay that revelation. This idea of the scars getting so thick you cannot feel, and the pain of allowing oneself to feel, of those scars being ripped off, echoes all the way back to GotM and Whiskeyjack’s “armor” that he tried to encase himself in (just as unsuccessfully) to save himself those feelings.

And then another great, moving moment—this parade and salute. And once again, one of my favorite techniques, as we move from mind to mind of the “grunts”—sometimes some comic relief, sometimes some painfully sharp moments of poignancy: Kisswhere’s vision of a normal future, Helian’s recollection of the young boy who died, Urb’s love for Helian and his silence, Widdershin’s pride, Deadsmell’s pride and also his desire to live, even if it means listening to Throatslitter laugh. And here at the end, just before this battle, it’s nearly impossible as a reader not to fear that we’re getting these moments so we hurt all the more when some of these characters die. Which makes going forward all that more painful.

Love this idea of the coin—the respect—the paying it back, the not knowing what to do with it, the sense that every soldier has, that will always haunt them, of those they left behind.

And then that embrace between Fiddler and Hedge. If Erikson had killed one of them off without a reconciliation, he’d have been dead to me. Dead, I say. Dead.

And another beautiful, understated moment—Saddic and Badalle, and especially Badalle’s last line about will they ever see them again: “just close your eyes.” Always and forever, as long as they will live, they will see them. Perfect.

Just as perfect as Kindly laying a hand on Pores and not giving him an order. And Pores’ shock. Again, I love the understatement.

Blistig. What a revelation that was from Tavore to him. First to remind him of how his life could have gone (which would only increase his bitterness). Then to tell him how it actually would have simply ended quickly via assassination thanks to Rel. Then to tell him it wasn’t for his soldiering or command style that he was saved, but to keep the memory of the Wickans and Coltaine alive and true. And who indeed could have foiled a Claw in his/her attempt to kill Blistig? Interesting question.

As is the one about just how Tavore plans on dealing with the Forkrul Assail sorcery without her sword. A question her officers have as well. I love that discussion too: “Hey, you gonna get possessed by a god again and kill everything in sight with your knives?” Nope. “OK, how about you—you gonna turn all icy cold again and kill everything in sight?” Nope. “Hmm, you with your worm god, what can you do?” “Got me.” All ending in Raband’s very pragmatic, down-to-earth, “well then, nothing to see here. Time to get ready…”

Note that reminder in this conversation of the jade stars—never too far from the narrative, those things

And yet another supremely painful moment with Tavore, such an enigma throughout this series, such a closed book, and yet how can you not feel for her, the depth of her loneliness as she reaches the head of the column.

As I said, lots of emotion in this beginning, coming after such a huge blow-up of a chapter, filled with its own emotional moments obviously—but big noisy ones. This is a nice move into the more quiet, the more intimate. Though of course, we still have another battle to get to.

Amanda Rutter is the editor of Strange Chemistry books, sister imprint to Angry Robot.

Bill Capossere writes short stories and essays, plays ultimate frisbee, teaches as an adjunct English instructor at several local colleges, and writes SF/F reviews for fantasyliterature.com.