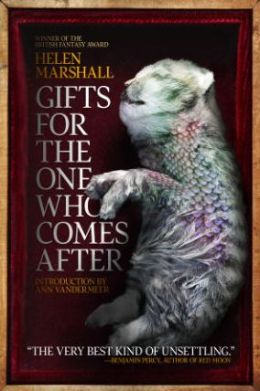

Ghost thumbs. Microscopic dogs. One very sad can of tomato soup. Helen Marshall’s second collection offers a series of twisted surrealities that explore the legacies we pass on to our children. A son seeks to reconnect with his father through a telescope that sees into the past. A young girl discovers what lies on the other side of her mother’s bellybutton. Death’s wife prepares for a very special funeral.

In Gifts for the One Who Comes After, Marshall delivers eighteen tales of love and loss that cement her as a powerful voice in dark fantasy and the New Weird. Dazzling, disturbing, and deeply moving, the collection is available now from Chi Zine.

Below, read an excerpt from “Ship House.”

“Ship House”

I am the law of your members,

the kindred of blackness and impulse.

See. Your hand shakes.

It is not palsy or booze.

It is your Doppelganger

trying to get out.

Beware… Beware…—Anne Sexton, “Rumpelstiltskin”

Her mother had become an old woman by the time Eileen came back to Ship House; she and the house in the shadow of Table Mountain had both sunk in on themselves, both had their backs broken by the winter rains and the too-hot summers of the South African Cape, their foundations crumbling to dust and gravel. Eileen’s mother wore old pearls and a red-and-white shift dress underneath a thin, woolen sweater. Her face was like Eileen’s face, almost. Her eyes had the white-blue of milk. Her hair was so thin she looked nearly bald.

“This is what happens,” Andrew had told Eileen before she left, “when you get to be her age. It’s no surprise that things aren’t quite working right.”

Andrew hadn’t come with her. Even though he knew she was the weaker of them, he had had not come. He had stayed to look after the Emma.

“Emma’s barely fifteen,” Andrew had said, “and, God, you know what she’s like, hon, but she’s not stupid. Let her see where she comes from.”

“No,” Eileen had said. “She couldn’t even play in the backyard there, not with, well, you know. It’s not safe. Not for my daughter. Not even at my mother’s house.”

So Andrew had not come. He had left her to do this alone.

Eileen had hired a special taxi to take her to Ship House upon the advice of one of her friends who still regularly travelled back to Cape Town. The regular taxis, she had been told, couldn’t be trusted. Her driver wasn’t white, but she supposed that was okay. She couldn’t tell for sure. He was polite. He took her bag and made sure she settled comfortably into the backseat of the car. Ten minutes later she was driving past the shanty towns with their little houses made of plywood, corrugated metal and sheets of plastic, the lines of laundry—bright blue, salmon, violet and indigo, God, the colours were bright! Unnatural!—fluttering in the sticky-hot breeze. The taxi made its way up the side of the mountain. All of a sudden, there it was: the hard ridge of the South African coastline laid out beneath her and Table Mountain looming above, thick and exposed as a varicose vein.

It was home.

It was home, it was home, but it didn’t feel like home any longer.

And when Eileen embraced her mother, her mother sank into her arms the way a cellar sinks into the muck: in three awful, slow stages.

“Oh, mother,” Eileen said.

“You’ve come back.”

“It’s time for us to be done with this place,” she said. “You can’t be trundling around with no one else here. You’ll slip and break something, and then what will we do?”

“Nothing, dear,” said Eileen’s mother. “I’ll just lie there until they find me.”

“No one will find you, mum.” Eileen disentangled herself carefully.

“Shush up, daughter mine,” her mother whispered. Her teeth clamped down. Snap. And then she smiled again. “There’s someone who will find me here.”

“There isn’t, mum.” (An old fight.) “That’s why I’m here.”

The wind plucked at her mother’s hair like harp strings, setting them loose to float in the air. It was January—but even the wind blew hot here on the other side of the world. Eileen had forgotten the tang of the salt air; milkwood, gladiolas, and freesias; underneath it all, the bitter-sick smell of the Caltex Refinery. The way the heat hung in the air like a second kind of light. Suddenly she was five years old again—back when things had been safe, back when she had learned the stories of the grandfathers: fairy tales, the kind in which stepsisters were left mutilated and forced to dance in hot iron shoes, the stories of Hansie and his sister Grietjie lost in the woods, the story of Raponsie and her long ladder of hair, and Repelsteeltjie, Granny Tamsyn’s favourite. The stories had scared Eileen viciously until she begged her mother to sit next to her bed through the night. There were other stories too, how the elephant got its trunk and the sing-song of Old Man Kangaroo, but it was the old tales she remembered best, the ones she had heard at the feet of her uncles, her great-aunts and her grandmother.

“They’ve all gone now,” Eileen told her mother, “Jacob and Rees, the great-aunts Johanna and Eirlys—Granny Tamsyn was the last but that was three, four years ago.”

“That’s not right,” her mother said. “I just saw Tamsyn last week. She brought me koeksisters from Bree Street. There might’ve still been some for you if you’d come sooner, but as it is I’ve gobbled them all up.”

“No, mum.”

“Maybe I’m thinking of someone else.”

“Let’s go inside, mum,” she said. “Why don’t you take me inside?”

*

The house was called Ship House.

It had been named, Granny Tamsyn had told her when she was little, by one of the grandfathers who sometime during the war—“Which war?” she had asked; “Shush up, dearie,” she had been told—had been stranded on a massive boat in the middle of the ocean. This house—this rambling half-mansion of a thing with its twelve arches and three terracotta roofs, its silences and croaks, its rooms so lush in daylight and so deeply oppressive after sundown when the heat of the day sunk into its bones—this house, Granny Tamsyn said, had reminded him of his time adrift. Eileen had never questioned it as a child. The house sat so perfect and still in the shadow of the mountain. Like it could wait forever. Like it needed no one—the waiting was enough.

Now Ship Housefelt strange on the inside to Eileen: too small and too large at the same time. The boards her mother passed over silently creaked under Eileen’s feet. “Go home,” they groaned. “Leave us to our ways,” they whispered. “Traitor,” they hissed.

Eileen wrestled her suitcase into the vestibule, grunting and sweating in the flush midday heat. Dust motes skittered through the light, settling on the gleaming backside of a giant ebony elephant. Her feet tangled on a coarse pink-and-blue rug. What would she do with all these things when she packed them up? They wouldn’t fit in the apartment back home. She ought to call Andrew, she knew, but—

“Come along, my button,” her mother said, “don’t linger.”

—would there even be a working phone? Had anyone bothered to keep up the payments to the electrical company?

“I thought you arranged for a cleaning service. Dr. Jans said you had.”

“I did,” her mother said. She paused to straighten an old photograph of the cable car that ran up the side of the mountain. “But I cancelled it. I don’t like them touching my things. Not them. Fingerprints everywhere. Strangers running through the house!”

Eileen didn’t say anything to that, but she felt a pang sharp as a needle.

She abandoned her bag in the hall, and followed her mother over the step into the sitting room where the family used to gather in the old days. “Quiet,” whispered the boards. “Let her sleep, let her rest,” they muttered.

Let her rest. Yes, she thought. Let her rest in the ground. In a little grave behind the house.

She shook her head, tried to unthink the thought but it sat like a stone in her mind. She did not want to think that way about her mother. But it was hard, sometimes. Oh, but it was hard. Andrew should have come, he should have, he should have, he should have, he should have—

The sitting room was as Eileen remembered it. There was Granny Tamsyn’s seat, and the matching set for the great-aunts Eirlys and Johanna, and for the uncles Jacob and Rees. Three generations had gathered here. The years had accumulated in the house: they were a weight, a presence, substance, form, smell. They clung to her fingertips like dust when she touched the ancient upholstery. Eileen helped her mother into her proper place. Her brittle knees clicked together under the white and red patterned dress like marbles or fine-boned china.

“They steal things, you know.”

“They don’t, mum.”

“They do. They come up from the ravine. They come at night, while I’m sleeping. And they take things.”

“Oh, mother,” said Eileen. “Oh, mother. It’s okay. Please don’t fret. I’m here now.”

And then her mother’s hand was in her hand, and they were clinging to each other. Adrift. The only two passengers left on the ship.

“No,” her mother said. “Oh, no, no. They have such little feet. Such little feet pattering across the floor, coming to take my things away.”

“No,” Eileen whispered. “I’m here.”

“Oh, lovey,” she said. “They do not care. One is as good as two. One has always been as good as two when they come for you.”

The men came in the night. That’s what her mother had said.

Oh, mother, she thought.

Eileen was in her room now. Her very own room. She hadn’t called Andrew to let him know she’d got in as she’d promised, but, well, it would be late at home wouldn’t it? Or perhaps it would be early. Time flowed differently here, and she hadn’t caught the rhythm of the new hours yet. And what would Andrew say anyway? “She’s old, Eileen,” he would say. “Of course, she’s like that. It’s a shame, darling, but it happens.”

And Eileen was tired. She was very tired. And the room had beckoned to her. Her own little room. Her own sweet place, tucked away on the first floor. The same green walls, the same paisley curtains she remembered. The same pale orange shaft of light when the sun began its slow descent below the crest of Lion’s Peak. What a sad strange place it was, this room of hers. It looked nothing like Emma’s room back home, even though she had been much the same age, close anyway.

There were two twin beds, identical in size and shape and dressing, both with the same twisted iron headboards and the same loosely coiled springs. Beds for boys, really. Not for a little girl. Granny Tamsyn had said they belonged to her mother’s younger brothers—Jacob and Rees—when they had been little. The bed on the right was hers. She had never slept in the bed on the left.

There were old school notebooks on the shelves filled with her childhood books: an ornate collection of the tales of the Grimm Brothers done up with gold trim, alongside a dog-eared Afrikaans textbook, biology lessons and history notes: the dates of the first and second Boer Wars, the Krueger telegram, Mandela’s imprisonment.

Ja, she thought, and goeie naand. Good evening.

All of it such a long time ago.

The sheets she had claimed from the closet were stale and thin, but comforting nonetheless. By habit she had made both beds. She had always done that—kept the other bed made. For a sister, maybe. She had thought Emma might stay in the room if she ever came over to see the house. They could have shared it together. For a little while, anyway.

There were no sounds from outside. Silence. She could almost imagine the lonely expanse of the ocean all around her as the house bobbed up and down. Ship House.

Sleep grabbed at her. Twisted. She was caught in its net even though the sun still hung low in the sky, lighting up the black bulk of Table Mountain and, northward, the bare edges of Lion’s Head.

She was asleep, she was asleep.

And then she was not asleep anymore because the men had come.

This is what the men said to Eileen, ugly as fear, monstrous looming things that they were: “Do you remember my name?”

And this is what Eileen said to the men: “No, of course not, who are you?”

And the men grinned their horrible, split-faced grins, and their sharp, hooked nails twisted into her skin.

*

When Eileen woke it was to the sharp tang of vinegar in the air.

The smell made her think of the harbour. Getting thick bundles of fried fish wrapped in newspaper with Jacob and Rees. So hot, but then the way her teeth would break through the batter to find the cod so sweet on the inside. They used to sit on the docks together and watch jellyfish floating like little Coke bottles beneath their sandals. Rees had found them for her in Kramp’s Synopsis of the Medusae of the World—“Just a little sting,” he had warned her, “like a pinprick or a tack. Like your first kiss, over with quickly, ja? But then you are dead!”

Eileen felt dislocated. Lost in the memory. But then she heard her mother singing.

“Bobbejaan climbs the mountain,” she heard, “so quickly and so lightly—”

It was an old South African war song her mother had sung to her as a child. Like so many things from her childhood, its meaning had twisted over time and taken on darker shades: the Voortrekker, the endless feuds and fighting. At the heart of it was bobbejaan climbing the mountain, ceaseless and relentless.

Eileen swung her legs out over the side of the narrow bed. The bed on the left—Jacob’s, or had it been Rees’s?—was untouched.

“Mum?” she called out. She didn’t know what time it was, but there was hot, buttery-yellow sunlight streaming through the windows. The room was picking up heat like an oven. She’d lost half the day already.

“Eileen,” she heard through the walls. “Be a darling, will you? Give your mother a hand.”

She found her mother in the elegant powder-blue bathroom off the second hallway, bent like a willow over a porcelain sink. She had stripped off her shirt, and her hair hung wet and dripping into the basin. Her body was so thin, the skin translucent as onion paper. Eileen could count the fluted bones of her shoulder blades.

Her mother turned at Eileen’s shadow in the doorway, and it was like watching the gnawed gears of a clock attempting to spin.

“You remember bobbejaan, darling?”

Eileen said nothing for a moment, struck by the sight of her. And then: “Ja, nee,” she muttered. “The baboon climbs the mountain to torment the poor farmers. It’s not a very nice song, mum.”

“Most childhood songs aren’t,” she clucked. “But they do their job. Do you mind pouring for me? It’s such a chore with my arthritis.”

Eileen took the silver jug her mother had left out on the vanity counter, and breathed in the vinegar sweetness of it. She had washed her hair that way every morning that Eileen had lived in the house. It was a kind of ritual.

Eileen poured the water over the mother’s downturned scalp and smoothed the soap out gently. She fetched a towel, patted away the dampness. She flinched, for a moment, as her fingers pressed against the hard shape of her skull.

“Mum,” she said, her tongue slow in her mouth. “You know why I’m here, right? You know that Dr. Jans called me about the fall?”

“Of course, darling,” she said. “But it was such a little thing.”

“It wasn’t, mum. Dr. Jans said you could have died if no one found you. You can’t live here on your own.”

Her mother took up a silver-backed brush with fine white bristles and began to run it through her hair. It whispered like a scythe as it fell from crown to waist, over and over again.

“Ja,” she muttered. “Whatever you say, daughter mine.”

“Please, mum.”

“Stupid child,” she muttered.

“What?”

Her mother’s mouth twisted into an ugly scowl.

“You just want my things!” her mother shrieked. “You want my blessings! My gifts! Just take them, you ingrate! Take what you like. They don’t mean anything. Here, take this!” Her mother flung the hard-handled brush with bruising speed. It bounced off Eileen’s flinching shoulder with an audible crack, and spun into the jug of water, which crashed again the dark blue tiles.

“No, mum!” Eileen cried out, rubbing viciously at the spot the brush had struck her. She felt a wave of anger. She wanted to slap her mother. She wanted to…

Her mother was staring at her with wide eyes. She was trembling.

“You don’t want it? You must take it, Eileen. You must. It’s yours,” she said, and now her voice was quavering. She stared at the jug on the tile. “They’re yours, darling. You must take them with you. Please, darling, won’t you just—?”

“Please, mum,” Eileen begged. Her throat was raw. “I don’t want them.”

“You must,” she said, “You must take them.”

Dr. Jans had warned her it would be like this. When she was frightened. When she was unsure. Her mood could spin so quickly—but it still shocked Eileen to see that stranger where her mother had been.

“Oh, my darling. I should have protected you. I should have let you go more easily. We fought, didn’t we?”

Eileen turned away.

“Yeah, mum. We fought. But it’s okay. Children fight with their parents. That’s what they do.”

“I should have set the gas, shouldn’t I? Just let it leak out, ja? No one would have known. I should have done that for you.”

Eileen wrapped her arms around her mother. “Don’t say such things. Please, mum, don’t ever say such things.” Shivered.

But the thought stayed in her mind: the house quiet and still, surrounded by the dark expanse of ocean. And not a passenger on board. Beautiful. Still as a tomb. The quiet hiss of the gas…

“It would have been better for you.”

Eileen took her mother in arms and held her, with the vinegar smell wrapped tight around the two of them, and her mother making little sobbing noises. Eileen felt the bones clicking against one another and she tried not to make a noise, to keep her lips perfectly sealed against her own tears.

Because her mother was right. It would have been easier. And she hated herself for thinking it, hated herself for knowing that it was true because, at the same time, it wasn’t. It wasn’t at all. It was awful to think of, her mother with her blue lips lying still on the bed.

She felt her mother stiffening in her arms.

“Brush my hair, would you, girl? Your father’s taking me out later. Jacob and Rees will mind you for the evening, so be sure you don’t give them any grief.”

“Okay,” Eileen pleaded in a soothing voice, “it’s okay.”

She began to run the brush in gentle strokes through her mother’s thinning hair. It seemed to calm her.

“Sing to me, would you?”

“Sure, mum. Of course.” The brush came down in slow, even strokes and the hair parted around it easily.

“Bobbejaan climbs the mountain,” Eileen sang, “so quickly and so lightly.”

The men were hairy: thick-bristled as boars. Their arms hung down around their knees, bald only at the pebbled skin of their elbows.

“Why did you forget our name?” the men said to Eileen.

Eileen didn’t want to answer.

They frightened her badly, made her skin pucker and crawl with fear as they touched her wrist, her hair, her neck. When they turned the wrong way, Eileen could see that they were not men at all, they were merely two halves of the same man—an ugly, dwarfish brute—a man split in half with his insides scooped out like a melon.

“I’ve never met you in my life,” she said.

“Oh, but you have,” said the first half, and smiled half a wide, white-toothed smile.

“And we have chucked your chin, and counted your fingers, and called you best beloved,” said the second half.

“If you did,” Eileen said, “it was a very long time ago.”

“We know,” said the men, “we know all this. It is you who have forgotten.”

“No,” said Eileen.

“Yes,” said the men. “You have been gone so long. But blood runs true, does it not?”

“Blood run true,” the other whispered.

“Two by two by two.”

“Such a pretty girl. Such a pretty, pretty girl come home to us.”

Emma had been such a pretty child.

Eileen loved her daughter the way she always imagined mothers were supposed to love their daughters. Cleanly. Effortlessly. Her love was transparent as a wineglass. Habitual as putting on a sweater.

When Emma was five she used to stand on the bed, a wobbly little girl, and run her hands through Eileen’s hair, her fingers never quite tangling in it but just gently touching her scalp, the back of her neck. Sometimes she would lay the sweetest little kiss on Eileen’s cheek and when Eileen turned, Emma would be smiling like an imp.

“I’ve got the apple in your cheek,” she would say. “I’ve stolen the apple of your eye.”

Emma didn’t know what the words meant, but she’d tear off, giggling, out of the bedroom until Andrew caught her up in his arms.

“Give them to papa?” he would say.

“Of course, papa. I stole the apples just for you!”

When Eileen had been pregnant with Emma, Andrew would sometimes run his fingers over the giant balloon of her stomach when they were lying in bed together, the house quiet as it would never be quiet again afterward.

“Look at you,” Andrew would say. “Grown so big. What have you got inside you?”

“An apple?”

“A cherry pip?”

“A girl?”

“A boy?”

“Could it be twins?”

“God, I hope not.”

But there had always been twins in the family, her mother told her. Jacob and Rees. Johanna and Eirlys. Always twins, except for the first generation, the first apple of the womb. Granny Tamsyn. Her mother. And her, of course. But there were two beds side by side in her room in Ship House. The one hers, and the other empty as an overturned basket.

Eileen and Andrew didn’t talk about the other baby.

They didn’t talk about the second set of kicks or the second heartbeat. And they didn’t talk about how when Eileen pushed and pushed, out had come two little bodies: one pink and thriving as a piglet and the other purple as a blood clot. They didn’t talk about that other little baby because Emma was such a good girl. A pretty girl.

“She just wasn’t ready,” Andrew had said to her, “She wasn’t even really there—not a little thing like that. She didn’t die, hon, she wasn’t even there yet. She was just a piece of a little girl. So hush up, my love.”

Eileen hadn’t cried for that other baby.

She hadn’t let herself cry.

She had clung to the little piglet child, and she had kept it close to her until it resolved itself into a small person, a scampering, singing toddler and then a coltish and wise youngster too old to suck her thumb, and, oh, time had marched on and brought her this strange teenager with a fringe of black hair cut below the eyes.

“Bring her to Ship House,” Andrew had told her. “Don’t deny her a grandmother. She has a right to see her.”

But Eileen had said, “No, she’s too little. Maybe when she’s older. She’ll go when she wants to go.”

She had said that every year.

And every year Emma had grown older and older until she could join in the chorus too: “I don’t want to,” she said. “I’ve got friends here. They promised they’d take me skiing during the break, before the snow melts. Have you seen the hills, mum? They’re beautiful. They’re just waiting for me. Can I go, please, skiing?” And who could deny her snow angels and skiing? Emma was a child of a different place, with her cheeks that went gloriously red when the frost kissed them.

And Eileen felt happy when Andrew relented. She felt giddy with relief. She didn’t push.

Perhaps Emma would go to Ship House one day. But not now. Not now. Not until she was older.

Some things just slip away from you.

*

The men slipped around her, moving the way that shadows move.

They stood, each on their own one leg, on either side of Eileen, their good sides toward her. But still she knew. Still she knew on the other side of each of those faces was no face at all. Their cheeks were cored apples with nothing inside them but white pulpy flesh.

“Come, my girl,” they said. “Let us show you the way.” Their voices were deep and high at the same time, forced through their strange half-bodies.

Eileen went with them. She couldn’t resist. Their strength was the strength of mountains. As they went they made the same strange dragging sound as wounded animals, each with their own single, bent knee.

“Bobbejaan climbs the mountain—” she giggled madly, unable to stop herself, but the first half shushed her with a dirty, stunted finger.

“We do not like that song—” he said through half of a mouth.

“—we do not like it at all,” the other one said.

Their bodies were warm. She could feel the air heating around them as if their skin was molten copper. There was a rank animal smell to them. They smelled of tunnels. They smelled of her mother’s hair as she brushed it.

And they were touching her. They were gripping her elbows, and she had to walk quickly and carefully between them. She was so afraid to touch any part of them. She hated the feeling of their oily, dirty fingers touching her skin. Their sharp, hooked nails.

“Where are you taking me?” Eileen asked them.

And then two men looked at each other, each with one good eye as blue as a robin’s egg.

“To see what is what—”

“—and which way the wind is blowing.”

“Are you going to hurt me?” She wanted to ask, but the question lodged at the back of her throat like a tongue depressor held too firm.

She did not like the way they moved, even with their good sides toward her.

She closed her eyes and pretended it was Rees and Jacob, one on either side of her. They were talking her to the harbour to watch the bottle-jellyfish bobbing beneath their sandals. She could smell the vinegar of the vendors. It smelled of the ocean. It smelled like the crisp and sweet taste of the fish. It made her mouth water.

“Oh, my lovely,” said the first one, “my little button. My dearie. You don’t know the story of this house, do you?”

“She’s let it drift out of her head—”

“—along with us.”

“She doesn’t remember the grandfathers.”

“Tell me,” Eileen cried out, for she was frightened of the little jig the men had to dance to stay with her. They capered, each with their one boot moving, their one ankle twisting down the hallway, and her dragged between them like a caught trout—down and down and down.

*

Eileen and her mother started in the downstairs: in Auntie Johanna’s room where the dust was thick and choking.

Eileen’s mother seemed all right. Her eyes were clear. She chattered easily as they went through the closets, pulling out gorgeous old dresses with big boxy shoulder pads in colours that had gone out of fashion years ago. There were hat boxes and shoe boxes, silk gloves with beading, and a portrait of a handsome man with a dark, pencil moustache—a darker, sharper Errol Flynn—hidden at the bottom of the dresser.

“She was a looker, your great-auntie was! A real choty goty,” her mother remarked as they stared at the old albumen browns and beiges. “You’ve got something of her features, I think, sometimes I see her when I look at you. I think, oh, that’s Johanna. She’s come back!”

Eileen didn’t remember Johanna very well. Just the vague floating image of tight, golden pin curls and a strange, low-lidded despair in her eyes. But Eileen didn’t look a thing like that. Eileen had her mother’s sharp cheekbones, narrow hips, and tiny plum-shaped breasts.

“Did I tell you the story of how I met your father?” her mother asked. “It was Johanna who did it for me, ja? The wild one. We were travelling together by boat to England, a big old steamer and, the noise, my God, the noise! She was older than I, your great-auntie Johanna was, but you know that, don’t you? She was supposed to be minding me, although I’ll never know why Granny Tamsyn chose her for as chaperone! She was just a few years younger than your grandmother but she was always a dotty old thing.…”

“I know the story.”

“You know the story?”

Eileen sunk her hands deep into a closet filled with pretty silk and gauze dresses. Beaded fringes tickled like spider webs, and for a moment she closed her eyes and it was like being a child at a party, seeing the world through stockinged knees, hiding under tables and stealing sweets off silver platters.

“Tell it to me anyway, mum.”

Her mother drew in a breath, blinked. “He was handsome. Ja?” she ventured as she stared at the photograph of the handsome man. “This isn’t him, of course. This was Johanna’s husband. The one who left her. The one who divorced her.”

“What about Dad?”

“Handsome,” she said firmly, “but in a way I had never seen before, not like Rees and Jacob were handsome. They were golden things, like angels, ja? But your father, no, he was crosswise handsome. We met him on the steamer heading out from the Cape of Good Hope. He’d just finished his degree and wanted to see the world a bit before he settled down. Got a job working for one of the mining companies. We all did it back then. The European Tour, Granny Tamsyn called it.”

“But you ran away.”

“I did!” she laughed. “There was your father, this handsome, young engineer. And you know what Johanna said to me? She said, ‘Away with you, girl, and—’”

“‘—don’t come home until you’re pregnant!’”

“She was a wild one,” Eileen’s mother fingered the photograph delicately. Someone had loved her once, Eileen thought. She tried to imagine her mother young and gorgeous, pretty as a new dress. “I don’t know why Tamsyn chose her to watch over me. Barely five minutes, and she sent me flying.”

“But she told Granny Tamsyn.”

“Oh, she did. Eventually. And Tamsyn sent the boys after me, but by the time they caught up with us in Paris I was round as a pumpkin with a ring on my finger, living in a little apartment on Rue Puget in Montmartre. But Jacob and Rees, well, when they came they talked straight to your father. They insisted that you be born in Ship House. Like all the others come before you.”

“Well.”

“I was such a happy old thing there, in that little apartment. Your father used to bring me pain au chocolat every morning! Ha! Imagine that. But my mother was a difficult woman to deny, and I wanted you, my dearie, to come into the world in your own proper place.”

Eileen looked down at the photograph tucked away in the cardboard boxes they had filled. The room was almost finished. But there would be other rooms. There were so many rooms. A whole hidden warren of them. She imagined if she went into the cellars there would be a tunnel—a long tunnel, a twisting tunnel—and if she followed it far enough she would find her way back home. Back to the other side of the globe.

“You’ll do the same,” her mother said. “When it’s your turn. You shall bring them back to Ship House just as you should, won’t you, darling? Won’t you, lovey? The twins? My little granddaughters?”

Eileen turned, touched a finger to her mother’s wrist. Her skin was powdery and loose, Eileen could feel the thick worm of a vein. The wrist. Her fingers touching against it, and the soft pulse of the flesh, almost dead, soft and clinging. Her mother was slipping away. Her mother was bleeding out one day at a time, like a cloth running out its dye in a damp, sticky puddle.

She suddenly had the urge to run. Ship House was a crypt. A grave. A coffin.

Her mother was speaking. “Lovey,” she said. “Johanna loved you, do you remember? You would watch her in the mirror some evenings. Just there, on the bed, as she brushed out her hair. How we all wanted to have hair like hers, how it curled in her hand like a little flower. She was so beautiful but then something happened to her… I don’t know what happened to her.…”

One part of Eileen was in the tunnels.

“. . . it was bad though, wasn’t it? The thing that happened?”

One part of her was walking away from all this. Stumbling through the darkness. Smelling the whisper of sulphur and dirt and copper and vinegar.

“Eileen?” her mother asked, and she twisted her arm, twisted it out of Eileen’s grasp. “What happened to Johanna? You’re hurting me, Eileen. Please let go.”

One part of her was almost free of this place.

But that was only one part of her.

She felt her fingers go slack and nerveless, and her mother touched dizzily at the place.

“Ellie?”

She would never be free of this place. Eileen could feel it taking hold of her. The old country. The dark country. With its blood spilled in the streets, its wars and its corruption, its buried bodies and its hidden resentments turned from whispers to violence. She remembered what it had been like to live here. What it had been like to go to school.

Every time Andrew asked her, she said it had been normal. She had gone to school the way that anyone had gone to school. She had read magazines made sticky by the heat of her fingers—could still find one or two of them if she looked on the shelves in the bedroom—had listened to Radio 5, not Pink Floyd, not The Police as Andrew had, because they weren’t allowed then, they were banned by the government, but there had been other bands, other music.…

Her life had been normal, she told herself. Her life had been the life of any young girl.

But it hadn’t been normal, had it?

When she was old enough she had left. She had run. There had been no chaperone. There had been no listless, beautiful Johanna with her low-lidded eyes telling her to make a baby and then bringing her home again when it was done. No. She had found her own crosswise husband, her own handsome man. And she had followed him to a place where the sun didn’t breathe down on the back of your neck, and all the while your mother insisting you wear a woolen vest—“Wear a vest to school, Eileen, you mustn’t catch cold! Please wear it. Wear it for me?”—even though it scratched in the heat, it made you feel sick inside, like you were wrapped up in all that wool, all that thick, clotted, scratching hair.…

She had gone away to a place that was cold and distant and shockingly free. She had been weak for leaving, she knew that. But she was weak.

“I’m tired,” Eileen’s mother said. Her hands twitched.

Eileen rested the photo of the rake with his pencil-thin moustache on top of one of Johanna’s old romance volumes where it skittered a bare half-inch across the fraying boards, caught in one of the unpredictable drafts that breathed through the hallways and set the windows rattling.

“I’m tired,” Eileen’s mother said. Her body had begun to shake like a leaf. “Oh, daughter mine, I’m so tired. It scares me sometimes, how tired I am. I’m always afraid here. Why did you leave, Ellie? Was it because of me? Did I make you leave?”

“No, mum,” Eileen said. Thought she said.

And then her mother was speaking again: “They come sometimes. In the night.”

“I know, mother,” Eileen said, one part of her cold and present. “This was too much, too fast. Come with me, mum. I’ll make us a cup of tea.”

And one part of Eileen watched her take her mother by the hand, a cold hand, a hand that quivered like a fine-boned pigeon. One part of her stroking, calming, soothing to rest that frightened thing she held, and all the while the other part she left, the other part, she did not touch, the other part she let free to roam in the darkness like a thread winding its way home.

*

“Come with us,” the men said, winding their fingers through her hair. Pulling her along.

“Where?” Eileen cried. “Where are you taking me?”

“To the room,” the men said, “in the centre of Ship House.”

Excerpted from Gifts for the One Who Comes After © Helen Marshall, 2014