Summer of Sleaze is 2014’s turbo-charged trash safari where Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction and Grady Hendrix of The Great Stephen King Reread plunge into the bowels of vintage paperback horror fiction, unearthing treasures and trauma in equal measure.

Just about every horror paperback that came out in the mid-’70s had to have blurbs on its cover comparing it favorably to bestselling horror novels like The Exorcist, Rosemary’s Baby, The Other, ’Salem’s Lot, and/or The Omen—that was simply a fact of publishing then.

But every now and again there’s a book like The Manitou, the 1976 debut from Scottish author Graham Masterton (b. 1946, Edinburgh), which is entirely its own kind of horror novel. With little use for good sense or good taste, Masterton uses only a few elements of those contemporaneous famous and popular works but then one-ups—nay, a dozen-ups!—them (for another example of his over-the-top style, check out his 1988 novel Feast) and gives readers a damn-near perfect example of vintage ’70s horror fiction.

Going in I knew a manitou was some kind of ancient Native American spirit, perhaps like the Wendigo. I knew it’d been a silly, sleazy ’70s flick with Tony Curtis. I expected little when I sat down to read, and then I actually finished the book in less than a day—it’s 216 pages in its 1976 Pinnacle Books paperback edition. Masterton does a brisk, credible job weaving the dated occult aspect of Tarot cards and reincarnation (yawn…) together with a Lovecraftian twist on Native mythology (yay!). The Manitou is a wonderfully trashy, outrageous read, fast-moving and heart-stopping. It took me by total surprise!

A prelude chapter introduces young Karen Tandy, who’s in the hospital baffling doctors with the strange moving tumor on the back of her neck that X-rays reveal—ready?—to be a developing fetus. A fetus. I know, right? Next chapter Masterton switches to first-person narration by wry skeptic Harry Erskine, a 30-something guy earning his living providing sham psychic readings (are there any other kind?) to little old rich ladies in a wintry, well-described New York City. Just before she enters the hospital, Karen comes to see Erskine about a disturbing dream she’s been having. The sense of doom and foreboding it brings her gets Harry to start thinking there might be something to this occult business after all: “I don’t mind messing around with the occult when it behaves itself, but when it starts acting up, then I start getting a little bit of the creeps.”

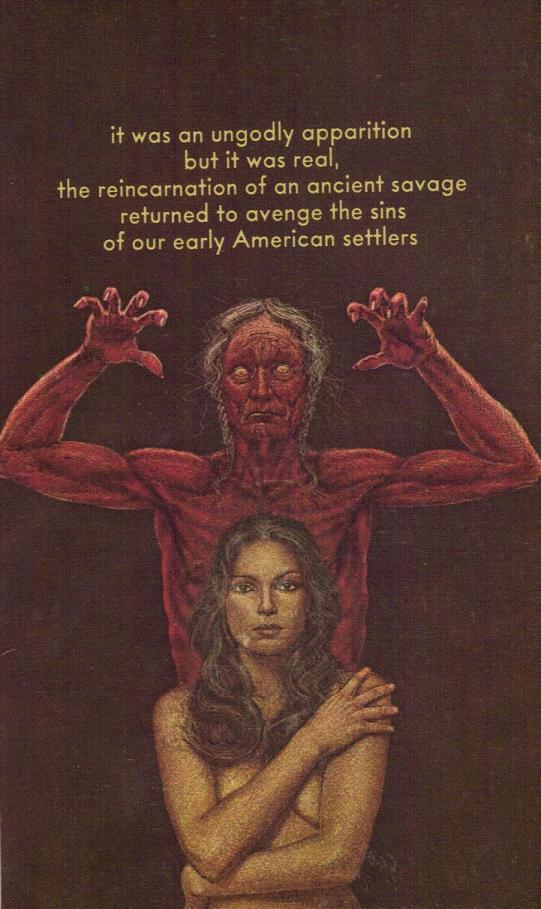

Cue more strange happenings that Masterton makes believably unsettling (particularly an old woman who simply floats across a room). Harry soon discovers the shocking truth: the fetus developing in Karen’s neck is the reborn spirit of the great and powerful Native American medicine man Misquamacus. Of course it is! And this being the 1970s and all, that phrase “Native American” is never uttered; instead, we get “redskin” or “Indian” or “red man.” And the ’70s thought that was being sensitive! Honestly it’s this kind of unfortunate datedness that I find endlessly amusing in vintage pulp fiction of the era.

As the tumor grows and the arrival of Misquamacus becomes ever more imminent, Karen’s life hangs by a thread and incredulous experts surround her. Harry consults the anthropologist Dr. Snow, who tells him about “Red Indian” spirits and how this Misquamacus was able to magically implant himself in Karen’s body, to be reborn 300 years after his tribe was exploited, exposed to disease and then run off by Dutch settlers. The “manitou” is his spirit, and we learn everything that exists has its own manitou…

Misquamacus now wants vengeance, oh you bet he does, and his occult powers are virtually unstoppable by modern scientific man. Only another medicine man fully in control of these powers can stop him—and perhaps even that is impossible. Can our inadvertent heroes even find a modern-day medicine man to fight back? Better find one fast, because here comes Misquamacus: his birthing scene is a gory delight, a masterful setpiece of body horror.

Karen Tandy’s body was thrown this way and that across the bed. She was dead already, I thought, or almost dead. Her mouth opened every now and then and she gave a little gasp, but that was only because the wriggling medicine man on her back was pressing against her lungs… The white skin at the upper part of the bulge was being pressed from inside, as if by a finger, trying to claw its way through… A long nail pierced through the skin, and watery yellow fluid suddenly gushed from the hole, streaked with blood. There was a rich, fetid smell, like decaying fish. The sac on Karen Tandy’s back sank and emptied as the birth fluid of Misquamacus poured out of it on to the sheets…

And he hasn’t even shown up yet! If all this is making you think “What the living fuck?” you’d be right. But Masterton makes all this sorcery work. What makes the engine run is that he’s entirely committed to his bit. We go right along with him. Despite its implausibility, I actually loved how everyone readily accepted the reality of what was going on: Karen’s doctors and parents, Dr. Snow, Harry himself. The media hears of bizarre goings-on at the hospital Karen is in, and cops show up as Misquamacus begins his mayhem. The only people who don’t believe what’s really happening are the police, and they come to a very bad and very gruesome end in a graphic scene; a really great shock moment that’s one of the best in the book.

A long-time editor (and one-time co-author with counterculture icon William S. Burroughs) Masterton’s style is effective, sometimes crude, sometimes patchy, lightened at moments with notes of black humor. And he really keeps the action going while also touching on broader, more thoughtful concerns. Harry’s skepticism about the reality of occult powers is treated with some ambivalence, and at one point Karen’s doctor, Jack Hughes, wonders aloud about the inherent guilt the white race must feel about their historically cruel and deadly treatment of Native Americans, and shouldn’t they feel at least a little sympathy for Misquamacus?

Which, as it turns out, is a terrible idea: as the story races to its climax, Masterton introduces a wonderful Lovecraftian tone as Misquamacus attempts to open the gateway for the Great Old One, aka The Great Devourer or He-Who-Feeds-in-the-Pit. You know that’s never good.

But it was not Misquamacus himself that struck the greatest terror in us—it was what we could dimly perceive through the densest clouds of smoke-a boiling turmoil of sinister shadow that seemed to grow and grow through the gloom like a squid or some raw and massive confusion of snakes and beasts and monsters.

opens in a new window![]() Graham Masterton offers horror fans a gory, pulpy, funny and even ridiculous read that strikes just the right balance between each of those aspects. Rife with eyebrow-raising absurdity, a sense of good fun and dread menace, The Manitou dispenses with rational believability in the service of a ripping horror yarn (Masterton would turn this conceit into an entire series). And I can’t really ask much more of a paperback horror novel than that!

Graham Masterton offers horror fans a gory, pulpy, funny and even ridiculous read that strikes just the right balance between each of those aspects. Rife with eyebrow-raising absurdity, a sense of good fun and dread menace, The Manitou dispenses with rational believability in the service of a ripping horror yarn (Masterton would turn this conceit into an entire series). And I can’t really ask much more of a paperback horror novel than that!

Will Errickson covers horror from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s on his blog Too Much Horror Fiction.