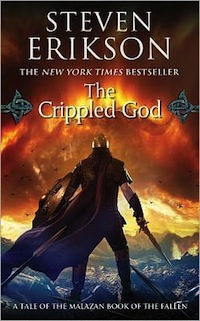

Welcome to the Malazan Reread of the Fallen! Every post will start off with a summary of events, followed by reaction and commentary by your hosts Bill and Amanda (with Amanda, new to the series, going first), and finally comments from Tor.com readers. In this article, we’ll cover chapter fourteen of The Crippled God.

A fair warning before we get started: We’ll be discussing both novel and whole-series themes, narrative arcs that run across the entire series, and foreshadowing. Note: The summary of events will be free of major spoilers and we’re going to try keeping the reader comments the same. A spoiler thread has been set up for outright Malazan spoiler discussion.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

SCENE ONE

The Snake continues on. Badalle feels the presence of other “ghostly things” hungry seemingly for “judgment” and desiring to ignore or flee from the Snake. Badalle thinks though “I am as true as anything you have ever seen. A dying child abandoned by the world… Flee from me if you can. I promise I will haunt you… Heed my warning. History has claws.” Saddic still carries his treasure trove and looks at it at every stop, something that frightens Badalle though she doesn’t know why. She comes to see even Saddic doesn’t know why he carries them, and she imagines his death, the butterflies coming down to feed on him, how she would try to make sense of that sack and fail, and then “I will know it is time for me to die too.” She thinks they have no more than one or two days left. Rutt tells her he’s gone blind, his eyes too swollen, and Badalle tells him the way is straight and clear; he can still lead. He stumbles, and Badalle, looking at them all and their state, grows angry and sings, her words carrying them away physically as she looks “for claws.”

SCENE TWO

Kilava stares at the Gate and the ruin of the Kettle Azath House—dead or dying. She had lied to everyone before so as to ensure their survival; she knows there was no chance of stopping the Gate from opening, of preventing the Eleint from coming in: “T’iam could not be denied, not with what was coming.” She believes she knows what most players will do—the Forkrul Assail, the Liosan, her brother (whom she gives her blessing to)—but the Crippled God is a wild card she thinks. She recalls his “fury and agony when first he was chained” and how “the gods returned again and again, crushing him down, destroying his every attempt to find a place for himself,” and ignoring his cries for justice, his “wretched suffering.” She thinks how in that way he was similar to so many mortals—”who were just as wounded, just as broken, just as forgotten… all that he had become—his very place in the pantheon—had been forged by the gods themselves.” She assumes the Crippled God knows the gods plan to kill him out of fear and because they “will not answer mortal suffering. It is too much work.” She assumes as well he is desperate to escape and will go down fighting. Looking at the growing Gate, she thinks it is nearly time to flee the coming “slaughter on a colossal scale.” None could fight what was coming, or, perhaps a few (too few), but she thinks “Let them loose. T’iam must be reborn to face her most ancient enemy. Chaos against order, as simple—as banal—as that.” She wonders “what of her children,” then thinks, “The hag’s heart is broken, and she will do whatever she can to see it healed. Despise her, Onos… she deserves nothing else—but do not dismiss her.” Rocks begin to crack and shatter as the House weakens further, and Kilava knows Kettle was “flawed… too weak, too young. What legacy could be found in a child left alone, abandoned to the fates. How many truths hid in the scatter of small bones?”

SCENE THREE

Gruntle feels Trake inside him, “filling him with an urgency he could not understand” to find a gate and he wonders what it is Trake fears so much. In this world not his own, he comes across nearly two dozen humans dead from disease, and he thinks “Someone summoned Poliel and set her upon these people. I am being shown true evil—is that what you wanted? Reminding me of just how horrifying we can be?… These people, someone used you to kill them.” If Trake was showing him this to awaken his anger, he tells him didn’t work—”All I see here is what we’re capable of doing.” He misses Paran and Itkovian and Harllo, Stonny and her son, parts of “a different life, a life long lost to him.” Out loud, he wonders what Paran would do—”We weren’t happy with our lots, were we? But we took hold of them anyway. By the throat. I expect you’ve yet to relinquish your grip… I’ve messed it up.” He knows from his dreams he has a “terrible fight” ahead, and senses it was time. He raises the dead to be his warriors, offering them something different than the misery they died in., offering a “better death.” They wake healed, and when he gives them the choice of returning to their people (if any are left) or seeking vengeance (he says they know they’ll lose), they join him and they veer together into “a rather big” tiger. They kill three pale men on the road (implied evil ones) and then exit the world.

SCENE FOUR

Mappo reaches the Glass Desert, finding it covered with bones. He thinks perhaps he is tiring of living, and he can be done with it all after he accomplishes his one thing to do. As he starts to cross, he feels “inimical” life and “intent”. Death, though, he now considers a release, and he wonders what it now holds, with Hood clearly absent: “What now waits beyond the gate? So much anguish comes in knowing that each of us must pass through it alone. To then discover that once through we remain alone—no, that is too much to bear.” He considers alternatives in his life—staying in his village, having a family, killing Icarium—but then believes he really had no choice. And had he a family, his eventual death would have pained them—”I could not bear to be the cause of their sorrow. How can one give so freely of love to another, when the final outcome is one of betrayal? When one must leave the other—to be the betrayer who dies, to be the betrayed left alive. How can this be an even exchange, with death waiting at the end?” A swarm of flies appear, than locusts, and butterflies, and he realizes “You’re all d’ivers… one thing, one creature—the flies, the locusts, the butterflies . .. This desert is what you made.” He tells it to semble so he may speak to it but the locusts swarm him, trying to break through his skin and failing, and he can feel the rage and wonders, “Who in this desert drove you way? Why are you fleeing?” He can sense it hasn’t sembled in ages, millennia perhaps, and it’s lost in the primitive parts of itself. He hears in his mind Badalle’s song of banishing and the locusts disappear. He wonders where this child of so much power is and thanks her, then thinks, “Child, be careful. This d’ivers was once a god. Someone tore it apart, into so many pieces it can never heal… All it knows now is hunger… [for] life itself, perhaps. Child, you song has power. Be careful. What you banish you can also summon.” He hears her, more faintly, “like the flies. Like the song of the flies.” Mappo heads off again.

SCENE FIVE

Silchas Ruin has rejoined Ryadd Eleis. He gives him the two Letherii swords, keeping the one Shadowthrone gave him, though he remains mystified as to its provenance, thinking he had known all the weapons forged by the Hust. He suspects Shadowthrone is “playing a game” by giving it to him. Ruin tells Ryadd the Eleint blood in him is a “poison,” one that he and his brother chose on their own out of necessity (what he calls the “fatal lure of power”). They believed with the blood/power of T’iam they could bring peace to Kurald Galain by “crushing every House opposing us… killing thousands.” When Ryadd says he is not Ruin, Silchas replies, “Nor will you ever be, if I can help it.” He tells Ryadd that Kilava has almost certainly convinced the Imass to leave their realm, that Udinaas, who understands the “pragmatism of survival” has probably led them away, getting help from Seren Pedac to hide from the humans. He thinks she will join them to hide her child away, protected by Onrack and the Imass. Ruin goes on to describe the coming of the Eleint through the Gate—”among them there will be the last of the Ancients. Leviathans of appalling power—but they are incomplete. They will arrive hunting their kin. Ryadd, if you and I had remained… we would in mindless desire join the Storm of the Eleint.” He explains dragons travel in threes to be safe, that when there are more it “demands the mastery of at least one Ancient… when too many of us gather in one place, the blood boils.” He informs Ryadd he’s going to leave, to “defend my freedom,” and when Ryadd wonders how he could do that, Ruin says because he himself is an Ancient. Too, he adds, when Ryadd asks if Ruin could dominate/compel him, that he has learned to resist Chaos’ seduction. Ryadd asks if his mother Menandore was an Ancient as well. Ruin says yes, all the first few generations of Soletaken are, but T’iam’s blood quickly became unpure. When asked about other surviving Soletaken, Ruin says there are a few and they will most likely fight the Storm as well. He explains he doesn’t want Ryadd there because if Ruin has to pay attention to defending both of the them, he’ll most likely fail at both; Ruin will end up enslaved by an Ancient. When Ryadd says “if you did the same to me, imagine how powerful you would then be,” Ruin answers that’s why dragons so often betray each other in battle—fear causes a first strike: “The Eleint revel in anarchy… in unmitigated slaughter.” His only answer to Ryadd’s “Who can stop them?” is, “We’ll see.” Ruin asks Ryadd to tell Udinaas he did what he promised (protected Udinaas’ son) and also to say that he [Ruin] regrets his haste in what happened with Kettle. Ryadd asks if Ruin is going to kill Olar Ethil for what she’d said earlier, but Ruin says she spoke the truth, and after all, they were “only words.” Ruin leaves.

SCENE SIX

Ublala dreams of his mace’s owner, a dragon-killer, a Teblor who broke the neck of a Forkrul Assail, who walked the Roads of the Dead to gain his weapon, who fell into drunkenness at having seen on his return “where we all ended up,” and who was going to be killed by the Elders then buried in his armor and with his mace under the Resting Stone.

SCENE SEVEN

Ublala wakes with Ralata next to him. After some sex talk, Draconus tells him they’ll walk through a warren today so as to avoid the desert ahead. Ublala says Draconus should just go on himself—Ublala and his “wife” could go somewhere else and Ublala can also finally dump this annoying dream-causing armor and mace. Draconus answers that he will in fact leave them soon, but not yet, and warns that Ublala will need to weapon and armor soon as well. He asks if Ublala knows when something is unfair and if so, “do you do something about it? Or do you just turn away?” Ublala answers he doesn’t like bad thinks, something he tried telling the Toblakai god, but they ignored him so he and Iron Bars killed them. Draconus is struck silent a moment, then says, “I believe I have just done something similar.” He tells Ublala to keep his weapons.

SCENE EIGHT

Rudd moves through the camp, thinking how the thirst is killing them. On the outskirts of the camp, he is met by Kalt Urmanal and Nom Kala, who tell him they are deserters from an army led by First Sword T’oolan. When Nom Kala asks if Rudd is a Jaghut (she says he has the smell of ice about him), he asks if he looks like one and is surprised when she replies she’s never seen one. When he learns that the army of Imass led by Tool wasn’t summoned by the First Sword, but by Olar Ethil, Rudd says, “shit” and asks what she’s planning. Now Kala thinks Olar Ethil seeks “redemption.” She adds, though, that Tool remains “defiant.” Kalt, however, calls Tool a “Childslayer,” and says they don’t know his intent or the enemy he will choose. He suspects tool seeks “annihilation. Their or his own—he cares not how the bones fall.” Rudd wonders if maybe the enemy Tool chooses might be Olar Ethil herself, something the two T’lan Imass hadn’t considered. When they warn Rudd about the impossibility of crossing the desert, saying a god died there but remains, he tells them he knows all that, knows as well it’s a d’ivers gone mindless. Kalt tell Rudd “We have come to you because we are lost. Yet something sill holds us here… Perhaps, like you, we yearn to hope.” Rudd calls up the Unbound, and Urugal appears to announce they are seven again, “at last the House of Chains is complete.” Rudd thinks to himself: “All here now, Fallen One. I didn’t think you could get this far… How long have you been building this tale, this relentless book of yours?… Are you ready for your final, doomed attempt to win for yourself whatever it is you wish to win? See the gods assembling against you… See the ones who stepped up to clear this path ahead. So many have died… You took them all. Accepted their flaws… and blessed them. And you weren’t nice about it either, were you, But then, how could you be.” He wonders how long ago the Crippled God’s plans began and thinks, “Win or fail… he is as unwitnessed as we are. Adjunct, I am beginning to understand you, but that changed nothing…The book shall be a cipher. For all time.”

SCENE NINE

Pores, Kindly, and Sort discuss Blistig’s barrels of water, which he has yet to open. Kindly says he’ll put Fiddler’s marines and heavies on guard. Pores tells Sort the Bonehunters are about to announce their death sentence, give up, and she tells him to stop it. She asks if he can guard the water with just the marines and when he says yes she leaves. Sort leaves thinking, “Talk to the heavies Fiddler, Promise me we can do this.”

SCENE TEN

Blistig tells Shelemasa to kill the Khundryl horses, saying they can’t afford to give them water. But Shelemasa tells him the Khundryl are giving the horses their allotment and instead are drinking the horses’ blood. He asks what’s the point, saying there’s nothing left of the Khundryl anyway and that Tavore only brought them along out of pity. Hanavat arrives and tells him that’s enough, reminding him of the Wickans who won an “impossible” battle while Blistig hid in Aren. She says if he wants to complain, do so to Tavore, who has told the Khundryl to preserve their horses, then tells him to get out. He leaves and she and Shelemasa discuss how the will see things through. Gall appears with Jastara. He tells Shelemasa he will be with his sons soon. Jastara flees through the crowd due to Shelemasa’s scorn, and when a young Khundryl girl (one of Fiddler’s scouts) is about to throw a stone at her, Fiddler (here to look for his scouts) orders her not to. He joins Hanavat, Gall, and Shelemasa and tells them “No disrespect, but we don’t have time for all this shit. Your histories are just that—a heap of stories you keep dragging everywhere you go. Warleader Gall, all that doom you’re bleating on about is a waste of breath. We’re not blind . . The only questions you have to deal with now is how are you going to face that end? Like a warrior, or on your Hood-damned knees?” He leaves and Hanavat laughs at his “no disrespect, then says Fiddler was right.” She tells Gall they will not die on their knees, but Gall says he has killed his own, their own children, and he needs her to hate him. She answers she knows. He says the Burned Tears died at the Charge, but she denies that then leaves with Shelemasa, whom she orders to find Jastara and take back her words—”It is not for you to judge,” complaining “how often [it is] that those in no position to judge are the first to do so.”

SCENE ELEVEN

The army moves on under the light of the Jade Strangers. Lostara watches with Henar Vygul as Tavore puts on her hood and prepares to lead the vanguard. Henar tells Lostara of the festival of the Black-Winged Lord celebrated every decade in Bluerose to summon their god, when the High Priestess dons a shroud and leads a procession of thousands though silent streets to the water’s edge, where at dawn she throws a lantern into the water to quench its light, then cuts her own throat.

SCENE TWELVE

Hedge is impressed that Bavedict’s wagon, filled with munitions, (code name “kittens”) is being pulled by three dead oxen, thanks to Bavedict’s necromantic alchemy.

SCENE THIRTEEN

Widdershins recalls his drunk, abusive father and his mother killing him. Then remembers getting his army name from his Master-Sergeant (Braven Tooth I assume).

SCENE FOURTEEN

Balm, Widdershins, Throatslitter, Deadsmell take over guarding Blistig’s water wagon from the regulars Blistig had assigned (who look surprisingly hale). Badan Gruk’s squad is on the other side of the wagons. Throatslitter worries about how few they are, saying when the thirst fever is on it’s trouble. The heavies, meanwhile, have been assigned to the food hauler wagons.

SCENE FIFTEEN

Urb’s group—Burnt Rope, Lap Twirl, et. al. discuss the Bridgeburners being all dead, save for a few, and how they can’t expect help if there is trouble. Urb tells them there won’t be because they have Bridgeburners marching next to them and “they got kittens.”

SCENE SIXTEEN

Fiddler thinks how “letting go” is the easiest choice, the other choices are unpleasant and expectant and “he so wanted to turn away from them all. So wanted to let go.” He walks instead, knowing what the Adjunct wants from him and his marines and his heavies, the unfairness of it. He hears Whiskeyjack’s “chiding” voice inside of him: “‘You’ll do right soldier, because you don’t know how to do anything else. Doing right, soldier, is the only thing you’re good at.’ And if it hurts? ‘Too bad. Stop your bitching Fid. Besides, you ain’t as alone as you think you are.” He sees figures walking ahead of them.

Amanda’s Reaction

There are some writers who are known well for writing beautiful prose, but I rarely if ever see Erikson’s name on those lists. And yet he’s capable of writing like this:

“Since the Shards had left, only the butterflies and the flies remained, and there was something pure in these last two forces. One white, the other black. Only the extremes remained: from the unyielding ground below to the hollow sky above; from the push of life to the pull of death; from the breath hiding within to the last to leave a fallen child.”

There is something very dark here about these butterflies being eaters of the dead—we so often associate butterflies with being light creatures, and pretty, that reading here about them stripping the skins from the dead children feels rather horrific.

We have watched these children suffer for such a long time now—it just keeps on getting worse for them, and it is painful to see.

Gosh, there is quite a lot to take on board with that section featuring Kilava watching the Azath House created from Kettle. In particular, this thought about Olar Ethil: “…and she well understood the secret desires of Olar Ethil. Maybe the hag would succeed. The spirits knew, she was ripe for redemption.” It seems as though Kilava is quite clear about what Olar Ethil and Tool are up to—just a shame she isn’t planning to share that with us readers, hey?

This is another interesting perspective about the Crippled God as well:

“In this way, all that he had become—his very place in the pantheon—had been forged by the gods themselves. And now they feared him. Now, they meant to kill him.”

It certainly shows the gods as having a lack of foresight or understanding, a real sense of fallibility—and that isn’t something we’re really used to seeing when it comes to gods.

How ominous does this sound about the arrival of the dragons?

“The destruction they would bring to this world would beggar the dreams of even the Forkrul Assail. And once upon the mortal realm, so crowded with pathetic humans, there would be slaughter on a colossal scale.”

Hmm, is Trake trying to get Gruntle to the gate where the dragons are going to come through to the mortal realm? It strikes me that Gruntle may be one of the few able to go toe to toe with a dragon.

Certainly Trake is willing to use his power to provide Gruntle with companions in the battle he faces ahead… That flexing of power feels as though it could only happen now that we’re heading towards the final convergence.

“Chains” is definitely another word in this series that had heavier connotations that just being a word—it seems carefully chosen. Here, especially, with Mappo, and the idea that every thought rattling in his head is like a chain. Mappo is certainly one of those so broken that he should be a follower of the Crippled God.

Wow! All those insects in the desert are d’ivers! And this is another example of how there are so many stories within the Book of the Fallen, and we can never know them all. This d’ivers is ancient, and has not sembled in thousands of years. It was once a god and someone tore it apart, into so many pieces it is unable to heal and find itself. There is one hell of a story there, and we are unlikely to ever know it.

And yet another hint of a story—but this one we might see in the Kharkanas trilogy. Where Silchas Ruin and his brother decided to take on T’iam’s blood in order to bring peace to Kurald Galain. Here is the disturbing part:

“Of course, that meant crushing every House opposing us. Regrettable […] The thousands who died could not make us hesitate, could not stop us from continuing.”

It seems to be one of those situations where killing millions might protect billions, but you still can’t see the humanity in the decision.

I somehow don’t think that Silchas Ruin’s plan to sideline Ryadd is going to come to fruition—something is going to bring this powerful Eleint onto the battlefield, I’m sure.

Hmm, is it coincidence that we hear all this stuff about the dragons coming, and then learn that the mace Ublala Pung has inherited is called ‘dragon-killer’?

These are some powerful words, and something that we have seen in our own world and time: “Simple need had the power to crush entire civilizations, to bring down all order in human affairs. To reduce us to mindless beasts.”

Another little addition to the mystery of Ruthan Gudd, where Nom Kala says that there is the smell of ice about him, and asks if he is Jaghut. It also sounds as though he was a contemporary of Gallan—before he became Blind Gallan.

It is chilling here, where Ruthan Gudd comprehends the scope of the Crippled God’s preparations—as he watches these two T’lan Imass join with the other five and become seven again: “the House of Chains is complete.” And a dark reminder that it is the Crippled God who poisoned the gates, and so is the cause of the Eleint being able to break through to the mortal realm. Is he relying on them to kill the gods who have trapped him and bled him? Scary stuff:

“He knew then, with abject despair, that he would never comprehend the full extent of the Crippled God’s preparations. How long ago had it all begun? On what distant land? By whose unwitting mortal hand?”

Especially scary because of how long-lived and Elder we are now understanding that Ruthan Gudd is.

Ugh, Blistig is a right bastard. It’s so hard to read his sections—seeing his despair and the pain he is causing other people, especially the Khundryl.

The scene with Hanavat and the other Khundryl, after Fiddler has come down on them, is so quiet and dignified. And where Hanavat tells Shelemasa not to wait too long—well, that makes me feel so sad about what seems the inevitable death they all walk towards.

And then a tiny spark of humour in the scene with Hedge, especially when Bavedict tells him the oxen pulling the munitions have been dead for three days now.

Aww, a carriage full of kittens!

You know the incredible thing? These Bonehunters and Bridgeburners are suffering so much, and yet they still find the will to bicker and talk and be part of each other.

Bill’s Reaction

That’s a great mixed image to open with—the butterflies “white as bone.” We usually think of butterflies as creatures of beauty and life so the contrast is particularly effective here, and appropriate considering how they feed, and then later to find out they are a d’ivers.

The imagery that follows, however, is simply horrific, though it is, as Badalle thinks, the horror of a truth that cannot be denied, or fled from. That idea of her haunting those whose bellies are full is starkly powerful, as is her line, “History has claws.”

There’s a wonderful (and again horrific) symmetry to this chapter, to these scenes. We have the Snake marching through this desert, dying of thirst, dropping right and left. And we have the Bonehunters, marching through this desert, dying of thirst, dropping right and left. Neither group is fully sure what it is they march toward, though many/most think they march toward their end. Badalle imagines Saddic dead and Fiddler’s group think of themselves as the “Walking Dead.” Both groups serve as an indictment—of neglect, of lack of compassion, of turning away. Both groups have leaders—Rutt and Tavore—who carry burdens (Tavore’s more metaphorical). Does the parallel extend to blindness as well? Finally, note how this first scene ends with the word “walk” and the last scene ends with the word “walking.”

Several references to Olar Ethil seeking redemption in this chapter. What sort of redemption? By what method? For what crime or sin? She’s an elusive figure, for all the talk we get of her, and all the times we hear her own words from her mouth.

Also lots of references to the Eleint coming through no matter what. It’s getting harder to imagine there will be any sort of intervention to prevent that at the Gate. Which isn’t much of a surprise I’d say—we’ve been set up for this dragon storm for some time now.

Interesting that Kilava, along with thinking she knows what Olar Ethil plans, also seem pretty sure about what her brother Tool plans as well.

The road to the revamping the reader’s view of the Crippled God continues in this scene, with Kilava’s imagery creating a sense of sympathy and pity and, of course, compassion for the god. The idea of his “agony,” of his “chaining,” how the gods did so “again and again,” is “wretched suffering,” the cruelty of the gods’ “turning away” from that suffering. And note there the parallel language to what we’ve seen Tavore use in her discussion of compassion: “Look into his eyes, Kindly, before you choose to turn away.” The way she blames the gods for what he became, and the way she thinks the gods will try and kill him out of fear.

The Crippled God comes in as well for some reshaping in our minds from earlier books when Gruntle in the next scene thinks of the horrors of the Pannion War (which had the CG behind it), but then thinks:

“But if he understood the truths behind that war, there had been a wounded thing at the very core of the Domin, a thing that could only lash out, claws bared, so vast, so consuming was its pain. And though he was not yet ready for it, a part of him understood that forgiveness was possible… and the knowledge gave him something close to peace. Enough to live with.”

Gruntle is thinking here of the Pannion Seer rather than the CG, but the analogy is pretty clear I’d say (not to mention there was arguably two wounded things—one behind the other behind the war)

I find the passage where Gruntle thinks back on those he misses and the ways his life might have gone to be quite moving. And also a bit ominous.

Speaking of ominous, opening up Mappo’s chapter with a dry sea of bones and then a few paragraphs later having him considering how tired he has grown of living, and thinking to himself he has but one thing to do, is just a bit gloomy as well.

And from there to the aching existentialism of the idea of why enter into love, into family (and one would assume friendship of a higher level) when it must by nature end in betrayal, i.e. death. Now that’s a prescription for a miserable life. This is one depressed Mappo here. I like too how Erikson in this philosophical discussion (and you know how I love these deeper digressions) continues to use the language of “walking.” Yes, it is “meaningless,” and yet the Snake continues to walk, and the Bonehunters continue to walk, and yes, they are the “Walking Dead,” because aren’t we all every moment of every day? And yet we “walk.” It’s hard not to fear, really fear, for Mappo in this scene. Not from the d’ivers (and it’s nice to have that cleared up a bit, though mystery still exists), but from his own thoughts.

Speaking of some “clearing up,” Ruin’s conversation with Ryadd is surprisingly informative and straightforward. Sure, there’s the whole where’s this sword from and why did Shadowthrone give it to me mystery that opens up the dialogue, but all that speech about the dragons and what happens in groups of them etc. is pretty easy to follow. And a “storm” of dragons would be a thing to see. Wonder if we will… So we’ve got the Eleint seemingly unable to be stopped from coming through, we have the Otataral Dragon being freed by our triumvirate of Elder gods, we’ve got Ruin saying he’s up for a fight as a dragon, we’ve got sly references to others as well (certainly we know several characters who veer), we’ve got a pair of characters who are sometimes dragons (hanging out with Olar Ethil if you recall), we’ve got some dragons Cotillion spoke to. Lots of dragons have been mentioned—will they all “boil” when the time comes? Talk about a convergence (a conflagration of convergences? Like a murder of crows?)

And how likely is it that Ryadd will stay on the sidelines, “safe”?

Like Ublala’s visions (how often have we seen this idea of a “fall”—appropriately so for this series title), not a fan of Ublala sex talk or of Ralata “relent[ing].”

What does Draconus know that makes him so sure Ublala will need his weapon and armor. And soon? (perhaps Draconus, like my Kindle, knows we’re almost halfway done). And what might it have to do with “fairness”? Note again that repetition of language: “Do you do something about it? Or do you just turn away?”

Boy I love the mystery of Rudd. “How the fuck do you know that?” indeed. Not to mention the “smell of ice” about him. And what does he know so well about “punishment. Retribution”? This certainly sounds like painful personal experience. Did he have the satisfaction once of vengeance? Of getting rid of some bastard(s)? And did that sense of satisfaction turn to “dust” in his mouth? Like he says, the T’lan Imass are indeed a walking metaphor for so much.

I do, however, like how his thoughts, so spot on about the T’lan Imass in general, are followed immediately by two T’lan Imass who have deserted an army, who do not seek vengeance, one of whom has never even seen a Jaghut—their alleged vengeance-soaked obsession. The universe always surprises…

Note how immediate Rudd’s response is to news of Olar Ethil meddling: “Shit.” Seems he knows her pretty well. The mystery grows. As it does a bit later when he knows so much about the god who died here, the d’ivers aspect, the way it’s lost itself.

Speaking of surprise, I like how he surprises the two T’lan Imass with his idea that maybe the enemy Tool chooses is Olar Ethil herself (something we as readers have a bit more insight into thanks to Tool’s POV)

Like the reader, Rudd wonders just how long this preparation for the Crippled God has been in place. Will we learn by the end of the series how far back this all goes? And who all was involved? We’ve certainly had a sense of the obvious convergence coming, with everyone now marching into or near the desert, everyone heading the same way. But with the “Now we are seven,” you get a larger sense of the pieces being set up, the game nearly afoot.

And once more, from the reader’s perspective, this line has to echo: “The book shall be a cipher.”

It’s one thing to have Blistig carp about what the army is doing, and another to think he doesn’t want to see the soldiers killed for nothing, but the sheer meanness and pettiness of his outburst at Shelemasa about Tavore taking them along for pity etc. is far worse in my mind.

And another parallel story of forgiveness and empathy and judgment with the whole Gall—Hanavat—Jastara—Shelemas quartet.

And Fiddler. Is there a scene this character doesn’t steal. Just those three words “Belay that scout!” is enough to get me. And I love, as did Hanavat, the “no disrespect” line he opens with before laying into the Khundryl, shaking them awake.

Of all the foreboding in this chapter, is there anything more grimly menacing, more creepily ominous, than that memory Henar has of the procession and the High Priestess cutting her own throat? That was an uber-powerful scene I thought.

One of the things I love about this series is you can have lines like, “I can’t believe I died for this.” That’s a classic.

Anyone think a wagon full of kittens might be important down the road? (even outside of the many Youtube videos Bavedict could make with them…)

I like the little background we get to Widdershins. The more we know these grunts the better I think.

Hard to believe something isn’t going to happen with these water wagons, with all the set up we’ve had about them.

Fiddler. Oh Fiddler. If you put Fiddler, Cotillion, and Quick Ben in the same scene at the end here, I might just explode. He just does what is right. How many times have we seen this? And while it seems a bit of a cliffhanger, I think the reader can make a pretty good guess at who those figures are he sees coming toward them. And knowing Fiddler, and thinking about what his interior monologue was saying here, it isn’t a stretch to predict what will happen. And it will stab you in the heart anyway, predicted or not. Right. In. The. Heart.

Amanda Rutter is the editor of Strange Chemistry books, sister imprint to Angry Robot.

Bill Capossere writes short stories and essays, plays ultimate frisbee, teaches as an adjunct English instructor at several local colleges, and writes SF/F reviews for fantasyliterature.com.