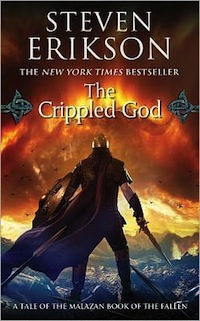

Welcome to the Malazan Reread of the Fallen! Every post will start off with a summary of events, followed by reaction and commentary by your hosts Bill and Amanda (with Amanda, new to the series, going first), and finally comments from Tor.com readers. In this article, we’ll cover chapter twelve of The Crippled God.

A fair warning before we get started: We’ll be discussing both novel and whole-series themes, narrative arcs that run across the entire series, and foreshadowing. Note: The summary of events will be free of major spoilers and we’re going to try keeping the reader comments the same. A spoiler thread has been set up for outright Malazan spoiler discussion.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

SCENE ONE

Pithy takes a moment’s rest from the horrors of the battle on the Shore. Skwish and Pully are dealing with the wounded—either helping with injuries or killing those past help. Pithy thinks she isn’t fit to be a captain. A messenger arrives to tell Pully Yedan Derryg has put her in command of the flank to replace a Corporal Nithe.

SCENE TWO

On her way to the command position, she tells a collapsed-in-terror soldier to get up and to the front line. Even as she mocks her own pretense at command, she can hear the soldiers around her respond. At the front, she sees Liosan for the first time and is shocked how much they look like the Andii save for white vs. black skin. Just as she notes how young and scared the Liosan looks, he’s killed by an axe blow to the head. There’s a sudden surge forward by the Letherii line. Pithy kills a Liosan, starts a chant of “This is ours,” then Nithe returns (minus his hand) to say he’ll take it from there. She pulls free for a moment and drops to the ground. When Skwish shows up with her knife, Pithy tells her to not even think about mercy killing her.

SCENE THREE

The Liosan retreat back through the breach. Bedac reports to Yedan that it was Pithy who led that last push.

SCENE FOUR

Yan Tovis watches as the post-battle scene. She knows this was a mere testing probe by the Letherii, that next time they’ll come with greater force and determination, and maybe the first dragons. She thinks again she will know kneel to this sacrifice, but she does plan to stand with her people: “It’s carved into the souls of the royal line. To stand here upon the First Shore. To stand here and die.” She wonders why people follow her and her brother when this is the result, she and Yedan “co-conspirators in the slaughter of all these people.” She sends a message to Sandalath that the first breach was stopped.

SCENE FIVE

Aparal Forge watches the wagons of wounded return, confirming that the Shake (or someone) has returned to Kharkanas and are fighting—“madness, all of it.” Dragons wheel above him, and he thinks how they have succumbed to chaos: “Son of Light [Iparth Erule], beware your chosen, not that the blood of the Eleint rises, to drown all that we once were.” Kadagar Fant joins him, saying they’d almost pushed through the breach. Forge tries to warn Fant about surrendering too long to chaos, saying Fant might lose control of his veered Liosan, but Fant dismisses the concern: “When I am veered they well comprehend my power—my domination.” Forge tells him Iparth Erule and the others don’t even semble anymore; they are wholly taken by the blood of the Eleint: “When they cease to be Tiste Liosan, how soon before our cause becomes meaningless… before they find their own ambitions.”

Forge wonders aloud if he needs to put a traitor on the White Wall again to remind his people. He notes how Forge seems to have lost his fear in giving Fant advice, and Forge says the days Fant stops listening to Forge is the day they will have lost, because he is the last one Fant listens to. He points out the dead on the way and when Fant says that’s because they opposed the Eleint idea, Forge says true, and now they’re dead for that opposition, and nearly a third of the Thirteen veered will not return. Fant says again how he can command them, Forge replies their “loyalty” will be mere appearance. Fant warns Forge he’s edging close to treason, but Forge shrugs it off. Changing the topic, Fant says he was surprised at how “weak” their opposition was, and he wonders if the true Shake are ended as a line and that they now face mere mercenaries hired by the Andii. Forge points out they fought well, but Fant scoffs, saying it’s just human stubbornness: You have to cut down every last one of them.” Aparal calls that the “surest way to win an argument,” and Fant is happy he’s back to normal. Heading off to take command, Forge warns Fant not to be the first of the Thirteen through the breach, telling him to let Erule or one of the others learn how the opposition has decided to deal with dragons. Fant agrees.

SCENE SIX

Forge wonders if this is indeed what Father Light wants: “What was in your mind when you walked… through the gate named for the day of your wedding, for your procession’s path into the realm of Dark? Did you ever imagine you would bring about the end of the world?” He refuses to veer into dragon form so as to not confirm to the legions they are led by dragons, by “the blood-tainted, by the devourers of Kessobahn.” He will hold to being Liosan. He plans on what to say to the troops, something about the inherent weakness of mercenaries and of humans—“pathetic,” even many of their great leaders. He wonders if one such is on the other side and thinks it unlikely. Looking at the gate, he thinks how that marriage had causes so much bloodshed, “shattered three civilizations. Destroyed an entire realm,” and wonders if Father Light had known, if he would have sacrificed his happiness for the sake of his people, and hers. He thinks Father Light would have, “because you were better than all of us,” and knows that no matter what the Liosan do to avenge Father Light’s failure, “nothing… will make it better. We’re not interested in healing old wounds.” He rallies the troops and when they roar, he thinks, “Their justness is unassailable. Kadagar is right. We will win through.” He tells one—Gaelar Throe—to find the human leader and kill him when they cross through. He looks ahead to their victory, to taking Kharkanas, killing Mother Dark (if she’s there), to a Liosan on the throne. Looking up, he thinks that Iparth Erule wants that throne. He gives the signal to attack.

SCENE SEVEN

Sandalath wanders the palace recalling an earlier time. Reaching one spot, she is truck by a memory of her running as a child in that area, and she wonders why she had run, thinking it hadn’t matter: “for that child, there was no refuge… Stop running child. It’s done… Even the memory hurts.” She reaches her former room: “Hostage room. Born into it, imprison within it, until the day you are sent away. The day someone comes and takes you. Hostage room, child. You didn’t even know what that mean. No, it was your home.” She pulls the door ring and hears something break and fall on the other side—“oh… no, no, no”—and opens it (locked from the inside) to reveal a room decayed with time. Inside she finds the bones of the last hostage:

“I know how it was for you… Mother Dark turned away. Anomander’s dreams of unification fell… I was long gone from here by then. Sent off to serve my purpose, but that purpose failed. I was among a mass of refugees on Gallan’s road. Blind Gallan shall lead us to freedom… We need only trust in his vision. Oh yes, child, the madness of that was, well, plain to see. But Darkness was never so cold as on that day. And on that day, we were all blind.”

She thinks how the child had trusted in the lock on the door: “We all believed it… It was our comfort. Or symbol of independence. It was a lock a grown Andii could break in one hand. But no one came to challenge your delusion of safety… It was in fact the strongest barrier of all.” She considers herself both queen and hostage—“No one can take me. Until they decide to. No one can break my neck. Until they need to.” She recalls dying, drowning—“Silchas Ruin came to us upon that road. Wounded, stricken, he said he’d forged an alliance. With an Edur prince… Emurlahn was destroyed, torn apart. He too was on the run. An alliance of the defeated…They would open a gate leading into another realm… find a place of peace… They would take us there.” She begs Mother Dark to give her rest, “blessed oblivion, a place without war.” Messengers report about the battle and she heads back to the throne room. As Withal gives her details she slips back into memory of Commander Kellaras telling Rake they’d pushed the Liosan attack back and Rake replying that the Liosan will keep coming through until there were all dead.

“Lord, is such the fury of Osseric against you that—”

“Commander Kelleras, this is not Osseric’s doing. It is not even Father Light’s. No, these are children who will have their way. Unless the wound is healed, there will be no end to their efforts.”

Rake notices Sandalath there and dismissed everyone else before speaking to her.

“He released you then—I did not think—“

“No Lord… he did not release me. He abandoned me.”

“Hostage Drukorlat—“

“I am a hostage no longer Lord. I am nothing.”

“What did he do to you?”

But she would not answer that. Could not. He had enough troubles… He reached out, settled a cool hand upon her brow. And took from her the knowledge he sought.

“No,” he whispered, “this cannot be.”

She pulled away… unable to meet his eyes… the fury now emanating from him.

“I will avenge you.”…

Shaking her head, she staggered away. Avenge? I will have my own vengeance. I swear it… she fled the throne room. And ran.

She starts murmuring, lost in her memory, and Withal holds her, pulling her out. She tells him she found the ghosts she’d gone looking for and it’s all too much. She says they need to run, she’ll surrender Kharkanas to the Liosan and hopes they’ll burn it down. But Withal tells her Yedan is in command and he will not yield—he is a prince of the Shake and now wields a Hust sword forged to slay Eleint. He tells her the sword knows what’s coming and it’s too late. She says Twilight is right not to be a part of this: “Is this all the Shake are to be to us? Wretched fodder doomed to fail? How dare we ask them to fight?” She asks the same of Mother Dark. Withal says the Shake are not fighting for Sand or High House Dark or the city—“They will fight for their right to live… after generations of retreating, of kneeling to masters. Sand—this is their fight.” When she says they’ll die, he answer then they’ll choose where and how, “This is their freedom.” She sends him away to be witness to it, and thinks, “We’re all hostages.”

SCENE EIGHT

Yedan tells his people the Liosan are coming again and in strength; he can see the dragons behind the barrier. Brevity says holding will be tough; they aren’t much of an army. Yedan replies neither are the Liosan, who are also mostly conscripts. When Brevity asks if that means they don’t want to be their either, he tells her it doesn’t matter, “Like us they have no choice. We’re in a war that began long ago, and it has never ended.” She wonders if they can even win, and he says, “among mortals, every victory is temporary. In the end, we all lose.” She doesn’t find that cheering, and he continues, “You can win even when you lose. Because even in losing, you might still succeed in making your point. In saying that you refuse the way they want it.” She still isn’t particularly inspired, and he thinks that’s overrated; you don’t die for someone else, you die for yourself—“Each and everyone of you, what could be more honest?” She tells him she thought it was all “about fighting for the soldier beside you… Not wanting to let them down.” He says you’re trying not to let down your “sense of yourself.” The attack begins.

SCENE NINE

Sharl, one of the Shake, thinks of her horrible younger life, raising her two brothers after her drunk of a mothers disappeared. She prepares to fight, her brothers beside her, and she is scared, wondering if this will be it for her family. Her brother Casel is speared, then Yedan and the watch show up. She and her brother Oruth advance with them as Casel is dragged away.

SCENE TEN

Pithy tells Brevity to take two Letherii companies to relieve the line where Yedan and the Watch advanced.

Amanda’s Reaction

This desperate war in the Breach, this hungry mouth that just wants to eat all who come before it—none of this is a pretty picture of what is happening on the Shore. Still, Erikson’s words are excellent at helping to show such a grim scene: “She let go of her sword but the grip clung to her hand a moment longer, before sobbing loose.” Just that one word ‘sobbing’ really helps to change this sentence and makes you really take notice of what a dark situation this is.

We then look back in time as the battle begins to see Pithy’s real feelings towards her sword: “The weapon in her hand never felt right. It frightened her, in fact. She dreaded spitting herself as much as she did some snarling enemy’s spear thrust.”

I also like seeing the practicalities of war here as well, the way that Pithy puts the mercenaries at the front, so there their only path of retreat is through loyal soldiers who are more unlikely to break and run.

And it’s always good to be reminded that there are two sides to every war, and that mothers on both sides of the conflict will be losing their children.

I don’t know if it is cruelty or kindness that has Skwish walking the battlefield and killing those Letherii who have fallen with injuries. I guess she is giving a swift death to those who would linger otherwise, but then Pithy’s ‘you fucking murderers’ makes it sound awful.

Oh man, this is poignant—Pithy using the courage of an orphan to get her back into the breach, and then him leading her by the hand: “And like a boy eager for the beach, he took her hand and led her forward.” This battle is no place for a child like that.

Well, this is direct and to the point, isn’t it? “Errant! They look like the Andii! They look just like them! White-skinned instead of black-skinned. Is that it? Is that the only fucking difference?”

Erikson is so able to create a little microcosm of a story—it’s fantastic to see Pithy here, so scared herself, threatening the ‘coward’ and then seeing him lunging into the attack as she goes to take command. It presents tiny little human touches in a seething battle.

Oh, that poor orphan boy…

And then a practicality of war that really isn’t pleasant to see—the Letherii commanded to use the bodies of the dead Liosan to help block the breach. And to make sure they’re dead before stacking them up. And then Yan Tovis’ view of that action: “The contempt of that gesture was as calculated as everything else Yedan did. Rage is the enemy. Beware that, Liosan. He will make your rage your downfall, if he can.”

Well, these two Liosan are worlds apart in attitude and levels of caution, aren’t they? Aparal becomes a character to respect as he watches the Eleint stay Veered, unable to return to Tiste form and regrets the path they have taken, while Kadagar is just an arrogant sod who, frankly, deserves to have all of his preconceptions crushed.

I like Aparal for this: “But was he not Tiste Liosan? I am. For now, for as long as I can hold on. And I’d rather show them that. I’d rather they see me, here, walking.”

The section with Sandalath Drukorlat is dark and has so many layers to it, so many whispers and so many secrets. I wonder if we will ever know more about her time as a hostage, trapped in the room as Kurald Galain was destroyed, sitting as a child while Mother Dark turns her face from her children.

That scene from the past with Anomander, especially, is a real glimpse as to part of what makes Sandalath the way that she is—and it also shows that history is often doomed to repeat itself, watching a situation where the Tiste Liosan tried to breach the wall against the Tiste Andii and faced the Shake.

Ahh! The Hust Sword was forged to slay Eleint—that is a bit of a coup for Yedan to be carrying around.

Wow, this conversation between Sandalath and Withal is so raw, and I can absolutely see both sides of view, where Sand says of the Shake: “Is this all the Shake are to be to us? Wretched fodder doomed to fail? How dare we ask them to fight?” And then where Withal replies: “The Shake will fight […] Not for you, Sand. Not for the Queen of High House Dark. Not even for Kharkanas. They will fight for their right to live. This once, after generations of retreating, of kneeling to masters.”

Bill’s Reaction

So much for the “glory” of war in this opening scene, with the “reek,” the screaming, the vomit, the blood pooling in the ears, the spitting, the coughing, the “spewed vomit,” the “fear and the shit and the piss.” The way so much that happens is accident or chance or chaos—Pithy “killing” a coward, her chant, where she ends up in the surge.

Craft-wise, I love (if one can use that word) that tiny, telling detail of Pithy opening the hand on her sword to drop it, but it remaining for a second before falling. I’m reading that as being due to the stickiness of the blood and gore on the hilt and in your hand—so much more effective to be alluded to rather than stated I think. And also a great metaphor for how it isn’t so easy to give up this violence, how you might want to “drop it,” to leave it behind, but you can’t. And also how it will stay with you even if you are no longer actively part of it. Another good metaphor as well a few lines later, with the “maw” of the blades, spears, etc. “chew[ing] people to bloody bits… no end to its appetite.” Then, we have another great simile that uses the technique of contrast to make the horror even worse, that image of the boy taking her by the hand and leading her through this reek and vomit and blood and killing, “like a boy eager for the beach.”

Note too the empathy of realizing there are/will be mourning mothers on both sides of this conflict, and of seeing the Lisoan “frighteningly young… his fear. His terrible, horrifying fear.”

And if this is the “probe,” what will it be like when the Liosan come through “in force”?

It is interesting in a fantasy with so many kings and queens and empresses that we get one wondering why people follow them if this is the result. We don’t get enough of that question in fantasies, I think.

Twilight’s thoughts make a nice transition as well to the other side (and I always like when we get the other side), where we see someone else (Forge) questioning what is going on. In this case, particularly the decision to drink the Eleint blood; already we’re told it has taken several of the Veered Liosan. If Forge, though, seems cautious, Kadagar is clearly just the opposite. His confidence is so supreme that it just about begs to be slapped down, doesn’t it? When you read someone talking about how his presence will “dominate” and turn the potentially disloyal loyal, and also starts talking about the enemy being “weak” and “no more” etc., we’ve often been trained as readers to expect a humbling about to happen. And of course, we know as readers that the Shake are not, in fact, “no more.” Which makes us expect that humbling even more.

This is a nice bit of parallel with Forge walking toward the troops and thinking of his speech, coming so close to Yedan talking about how he doesn’t believe in such things—the two commanders being set up one vs. the other here in more ways than the simple battlefield. And then again, just a few paragraphs on, when he wonders if there is a “great commander” amongst the opponents, and then thinks, “he doubted it.” Another humbling expected here?

For all that Liosan arrogance, it is kind of hard to argue against Forge’s view of humanity here: “Incapable of planning ahead beyond a few years at most, and more commonly barely capable of thinking past a mere stretch of days.”

A few hints of that deep past—the “Wedding Gate,” Father Light, a marriage that “had spilled more blood than could be imagined. Shattered three civilizations. Destroyed an entire realm.” Might we see this in Forge of Darkness or its follow-ups?

It’s interesting that after characterizing Forge as a thinking Liosan, a questioning one, a Liosan who thinks Father Light would have sacrificed himself for peace, turns so suddenly upon the sight of the Liosan corpses stacked like firewood on the other side—is this a Liosan trait, is it the “taint” of the chaos/Eleint, or a combination? And recall how Twilight had seen Yedan order those corpses stacked thusly in order to provoke just this response—rage. A rage she says Yedan, cool and calculating, will use against the Liosan. So once again, Forge is linked pretty tightly to Yedan. And again when he calls out a Liosan and assigns him a specific task—to kill Yedan.

From a huge battle waged on the Shore to a much more singular, much more personal one being waged inside of Sandalath. What a tease this scene is—so many questions raised in it. Why was she a hostage? What was her purpose and why did it fail? Why was her safety as a hostage (in a room “locked from the inside”) a “delusion”? Who is the “he” who “released” her (in Rake’s words) or “abandoned” her (her correction of Rake). How did she become “nothing” rather than a hostage? In Rake’s words, “What did he do” to her? What was it that so infuriated Rake and cause him to immediately swear to avenge her? Did Sandalath get her own revenge? Or will she yet? We don’t have a lot of series left—will these questions get answered by the end?

I like this shift at the end from our main protagonists to Sharl—the background story (one that could easily be grounded in our own world), the brothers, her fierce promise to do all she can to keep her brothers alive, her fear that this day will see the end of her family, her agonizing, heart-breaking litany of things she would do so that this horrible thing would end, would never be, the empathy she has in seeing her Liosan victim—“so childlike, so helpless,” this coming after the terror at her brothers’ “vulnerability,” the horrid detail (again, nothing glorious here), the terrible image of Casel “like a pinned eel.” It’s a powerful, powerful scene.

So much so I might have preferred ending on it, but I do like the way after this horror of battle scene we get the complexity of war, with Pithy thinking: “It terrifies us. It makes us sick inside. But it’s like painting the world in gold and diamonds.” If I read this right (and I may not be), it’s that dichotomy of war that while it is death and pain and ugliness, soldiers will often talk about how the whole world also comes alive in it. It reminds me of Tim O’Brien’s brilliant book The Things They Carried, in the story “How to Tell a True War Story”:

War is hell, but that’s not the half of it, because war is mystery and terror and adventure and courage and discovery and holiness and pity and despair and longing and love. War is nasty; war is fun. War is thrilling; war is drudgery. War makes you a man; war makes you dead.

The truths are contradictory. It can be argued, for instance, that war is grotesque. But in truth war is also beauty. For all its horror, you can’t help but gape at the awful majesty of combat. You stare out at tracer rounds unwinding through the dark like brilliant red ribbons… You admire the fluid symmetries of troops on the move, the great sheets of metal-fire streaming down from a gunship, the illumination rounds, the white phosphorus, the purply orange glow of napalm, the rocket’s red glare. It’s not pretty, exactly. It’s astonishing… You hate it, yes, but your eyes do not. Like a killer forest fire, like cancer under a microscope, any battle or bombing raid or artillery barrage has the aesthetic purity of absolute moral indifference—a powerful, implacable beauty…

Though it’s odd, you’re never more alive than when you’re almost dead… Freshly, as if for the first time, you love what’s best in yourself and in the world, all that might be lost. At the hour of dusk you sit at your foxhole and look out on a wide river turning pinkish red, and at the mountains beyond, and although in the morning you must cross the river and go into the mountains and do terrible things and maybe die, even so, you find yourself studying the fine colors on the river, you feel wonder and awe at the setting of the sun, and you are filled with a hard, aching love for how the world could be and always should be, but now is not.

Amanda Rutter is the editor of Strange Chemistry books, sister imprint to Angry Robot.

Bill Capossere writes short stories and essays, plays ultimate frisbee, teaches as an adjunct English instructor at several local colleges, and writes SF/F reviews for fantasyliterature.com.