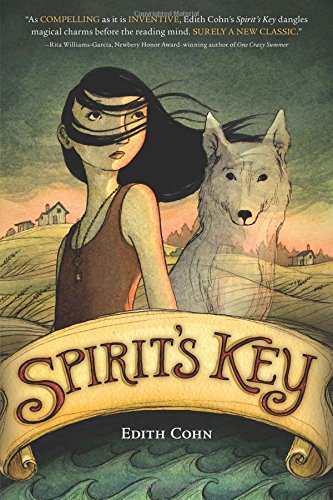

By now, twelve-year-old Spirit Holden should have inherited the family gift: the ability to see the future. But when she holds a house key in her hand like her dad does to read its owner’s destiny, she can’t see anything.

Maybe it’s because she can’t get over the loss of her beloved dog, Sky, who died mysteriously. Sky was Spirit’s loyal companion, one of the wild dogs that the local islanders believe possess dangerous spirits. As more dogs start dying and people become sick, too, almost everyone is convinced that these dogs and their spirits are to blame—except for Spirit.

Then Sky’s ghost appears, and Spirit is shaken. But his help may be the key to unlocking her new power and finding the cause of the mysterious illness before it’s too late.

Check out Edith Cohn’s debut novel, Spirit’s Key, available September 9th from Farrar, Strauss & Giroux.

1

Mr. Selnick’s Future

When I got home from school, every cabinet in the kitchen has been thrown open. There’s a mess in the living room, too.

“Looking for something?” I ask Dad.

He runs his hands through his normally neat hair, which at the moment sticks frantic in every direction. “Have you seen the candles?”

“I think they’re in my room. I’ll check. Is the power going to go out?”

Dad shakes his head. “Someone’s coming for a reading.”

My heart flip-flops with excitement. “Eder Mint?” Eder used to be Dad’s best client. But not even Eder has been in for a reading lately. It’s been two months, the longest stretch without business since we moved to this island. That was six years ago, before people came to trust that what Dad sees, happens.

“No, Mr. Selnick. He’s coming any minute,” Dad says, “and I need those candles.”

I dash to my room. Most everything we own is hidden in boxes. Dad likes to order supplies in large quantities. His stockpiling has created mountains of cardboard that rise up every wall.

Each room in our house is painted a different color, and mine is purple. These days, though, I have to lean my head waaay back to see the color, because Dad’s mountains go waaay up.

I dig fast, cutting the packing tape off box after box. “Found them!” I yell. Dad doesn’t mess around. There are enough candles here to light the whole island. I grab two, along with a burgundy bedsheet.

“What’s that?” Dad eyes the bedsheet with suspicion.

“I thought it might look nice draped on the table.” I shake out the sheet and cover the dinky card table with it. “See?” I stand back to admire it. “Now you have a little atmosphere.”

Dad frowns and mutters something about mumbo jumbo. Candles, atmosphere, and crystal balls are what Dad calls mumbo jumbo. Mumbo jumbo is for hacks, and Dad is not a hack. He asks to hold a person’s house key, the kind you use to open your front door, and as soon as the key is in his hand, bam! He knows.

It used to be that simple.

It used to be Dad didn’t need mumbo jumbo.

“You’re tapping into your power, is all,” I insist. “And it might help to dress things up a bit.” I grab two candlesticks from the bookcase and arrange the candles in the center of the table. “Nice, right?”

“I’m tired just looking at it,” Dad says.

I snap my fingers. “Coffee. You need coffee.” I rush to the kitchen to make him a pot.

Dad also didn’t use to need coffee in the afternoon. But lately nothing’s like usual. Dad is tired. He has trouble concentrating, and usually this soon after school I wouldn’t be home to help him. I’d be out with my dog, Sky, running up and down the sand dunes. Or swimming in the ocean. Or bicycling with Sky running alongside, or…

Well, the point is I’d be with Sky. And Dad would be breezing through his readings instead of scrunching up his face, worrying he won’t get it right.

When the coffee’s finished, I bring Dad a cup, but he doesn’t drink it. He catches a glimpse of himself in the hall mirror. He tucks in his shirt and presses down his hair. He restacks some boxes to make them tall and orderly.

Finally, he sits down and takes a deep breath, but his foot doesn’t stop tapping. There’s sweat inside the wrinkles on his forehead, and when Mr. Selnick bangs on the door, Dad knocks over a chair standing up to answer.

When Mr. Selnick comes inside, I set the chair back upright. The big man takes off his hat and plops down like he’s relieved to have the weight of the world off his feet. “Thanks, honey,” he says.

My name isn’t Honey. It’s Spirit. Spirit Holden. But Mr. Selnick calls everyone honey. Mr. Selnick is our neighbor three houses down and one across. I wonder what’s up. Dad has regulars, and then there are people who come only if something’s wrong.

Mr. Selnick hands Dad his house key, which is my cue to skedaddle. But my foot lands on one of Sky’s squeak toys. It makes the worst kind of noise in the silence and brings back the pain of Sky’s death like a crashing wave.

Dad doesn’t notice. He’s busy lighting the candles. The light reflects off the bedsheet and casts a strange red color on Mr. Selnick’s face.

I pick up the squeak toy, a stuffed pheasant. Sky’s things are still the way they were when he was alive. The pheasant seems to look at me sternly with its yellow-stitched eye, like it would disapprove if I threw it away. It was Sky’s favorite toy.

I set it on the bookcase. I’m about to leave, but I pause when I hear Dad say something about a baldie.

“I don’t think this dead baldie in your yard means a negative future for you personally.” Dad scratches his head. “But I’m not sure.”

I shouldn’t eavesdrop. Dad caught me once when I was little, and he said listening to his private readings was like peeking at someone’s diary. Holding a person’s key, he said, I see everything they lock up. People trust me with their most private secrets.

Even though I wouldn’t tell anyone, it isn’t fair for me to know Mr. Selnick’s inner secrets.

But another dead baldie? Baldies are what people call the wild island dogs. We have bald eagles, too, which is how Bald Island got its name. But people call eagles sacred creatures. The dogs are the baldies, because they’re unique to our island. No one else in the world has dogs like ours.

Sky was a baldie. And anything to do with Sky has to do with me, so I don’t leave. I press up against the wall next to the bookcase with Sky’s pheasant.

“Not sure?” Mr. Selnick asks. “Is there something wrong with my key? This one’s a copy. Victor made it for me. Did Hatterask mess up my key?”

“No, no, your key’s fine. Don’t worry.” But Dad pushes Mr. Selnick’s folded money back across the table. “This reading is on the house.”

Dad never does readings on the house. His readings pay for our house and every box in it. I get that same sweaty feeling I got the day Sky wasn’t waiting for me after school. Like something’s bad wrong and I need to stick my head in the freezer to cool off and think clear.

Mr. Selnick is about twice as big as Dad. His gut sticks out under his folded arms like a shelf, and his large shoulders square back like he means not to leave until Dad spits out something more specific. “Whatever it is, you best lay it to me straight.”

Dad takes a sip of coffee, then picks up Mr. Selnick’s key again. He closes his eyes and begins to rock. Back and forth. Back and forth. Then he shakes like he’s cold, shivering until he jumps up and drops the key on the table like it burned him. “There’s danger ahead.”

“Dag-nab-it! I knew that baldie paws up in my yard was an omen.” Mr. Selnick shakes his finger at the air. “I told my wife: The devil’s after us.”

“Get Jolie and the kids. Pack your bags.”

“What?” Mr. Selnick looks dumbfounded.

Dad walks to the door. “You have to leave the island.” He stares hard at Mr. Selnick. “Tonight.”

2

My Today

“Leave the island?” Mr. Selnick repeats, as if Dad can’t possibly be serious. He lifts his large body out of his chair like he’s got time to spare. “I’ve lived on this island since I set foot on this earth. I’m not a-goin’ anywhere. If the devil wants me, he knows which house is mine.”

But after a moment, Mr. Selnick doesn’t look so sure. He picks up his hat and twists it like it’s wet and needs wringing. “What did you see? Tell me what I’m up against so I can be ready.”

“The best advice I can give you is your own,” Dad says. “Leave this island.”

I suck in a breath and hope this means what I think it means.

“I told you I’m not a-goin’ anywhere.” Mr. Selnick shakes his head. “I never said I was.”

“I saw your face covered in dirt so black I almost didn’t know it was you,” Dad says. “You were wearing the same blue plaid shirt you’re wearing right now, and you turned to Jolie and said, We should’ve left the island.”

I’m so relieved I almost let out a whooping wowzer right there and turn myself in for eavesdropping. A real vision! This is the kind of reading islanders have come to expect from Dad.

“I intend to die here just as I was born.” Mr. Selnick puts on his hat like it’s some kind of statement to permanence.

Dad nods. “I understand. Our keys are an important reminder of who we are and where we live. But I’m required to tell you the truth as the key told it to me.”

That’s the problem with the gift. People don’t always get the future they want. One time when Dad gave someone bad news, he and I had to leave town. That’s how we came to live on Bald Island. This little boy got hit by a car. Dad saw it while holding the mother’s key. The boy’s father decided Dad made it happen, or had the power to unmake it happen and didn’t. Dad does his best to prevent disaster, but he can’t control everything.

I was only six years old at the time, so most of what I remember is that when we moved we couldn’t bring Mom with us.

Mr. Selnick curses loud and slams the door on his way out, which makes the pheasant fall off the bookshelf, which makes Dad catch me eavesdropping.

Oops. I wave hello-there fingers at Dad.

“Come on over here next to your old man.”

I join Dad at the card table.

He picks up his cup and takes a long sip like he’s trying to clear his mind of the ominous vision he just had. “Mmmm. This coffee has spirit!”

I beam because Dad only uses my name as an adjective if he’s pleased. “Is Mr. Selnick going to be all right?”

“I’ll check on him after he’s had time to calm down,” Dad says. “He didn’t believe me when I told him about Poppi either, but he always comes around.”

Dad had predicted the birth of Mr. Selnick’s daughter, Poppi, even though Mrs. Selnick swore she was long done having kids since her two other children were already grown.

“The future can be frightening. It’s our responsibility to help Mr. Selnick face what lies ahead.”

“He forgot his key.” I pick up Mr. Selnick’s house key. It’s ornate and old-fashioned like a lot of things on this island. I hold it in my hand like Dad does. I rub its jagged edges with my thumb. I close my eyes tight.

Dad says the keys in our life can unlock our tomorrows. He uses people’s keys to see their future selves.

Future. I flip the key in my hand over and over. Concentrate. Breathe. Imagine.

Nothing.

“I wish I’d inherited the gift.” I’ve been holding keys every day since I turned twelve. Dad got his gift at twelve, and so did Grandmother. But I’ve been twelve years old for six solid months. Dad says when the gift happens, I’ll feel different. I’ll know. I’d give anything to know like Dad, but it seems our ancestors decided to leave me in the dark.

“Now, don’t you worry,” Dad says. “Keep trying. It might happen yet.”

Dad is optimistic. He thinks one day I might get the gift, but he doesn’t know for sure. Dad doesn’t know everything. Each key decides what he should know. And our key won’t show him anything about us—our keys have never worked for him.

Dad catches me looking at the pheasant on the floor. “You can’t help others face their tomorrow if you can’t face your today.”

I’m not exactly sure what Dad means, but I think it has something to do with the fact that I haven’t gotten rid of Sky’s things.

After a few minutes of us sitting there, Dad enjoying his coffee, me having a stare-down with the pheasant, Dad blows out the candles. “Shouldn’t you get started on your homework?”

“Yeah, I have some catching up to do.” I haven’t exactly told Dad this, but I think he knows I haven’t done homework in fourteen days. That’s how long Sky’s been gone.

On my way out, I pick up the pheasant and then gather Sky’s other toys, his bed, and his bone. I kiss the pheasant’s plush beak and put it with everything else in the trash. I tie the bag and haul it outside to the can. Garbage pickup is tomorrow. Maybe if Sky’s things are gone along with him, they can’t hurt me anymore.

Spirit’s Key © Edith Cohn, 2014