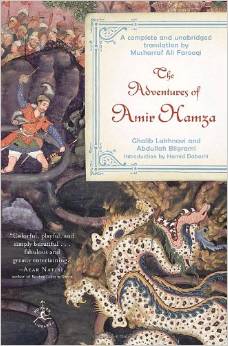

Here is a story to end all stories, a legendary tale of epic proportions, a fantastic riot of a narrative that even in its English translation retains the idiom and rhythm of its original oral form.

It follows the complicated adventures of one man, a hero to conquer all heroes, a man predestined to be ‘The Quake of Qaf, the Latter-day Sulaiman, the World Conqueror, the Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction, the Slayer of Sly Ifrit, and a believer in God Almighty—Amir Hamza.’

No one really knows where the Dastan e Amir Hamza came from, or when. One version of its origin story claims that the hero Amir Hamza was based on Hamza bin Abdul Muttalib, a man renowned for his bravery and valour, the uncle of the prophet Muhammad. The historical Hamza died in 625AD, and some say it was his courage that caused storytellers of the region to create this fantastic tale about him, adding familiar characters and folk tales to the story. Another source claimed the dastan—a heroic epic that was the heart of the ancient oral tradition, with Persian stories being popular in Arabia even during the advent of Islam—was created by seven wise men of the Abbasid dynasty in 750AD to cure the delirium of one of their caliphs. It seems that back then, the wise knew and respected how much power good stories can have.

Regardless of where the story first came from, it continued to be a popular dastan for centuries, existing in multiple languages across the Indian subcontinent and Arabia, travelling storytellers carrying it across borders in Urdu, Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Pashto and Hindi. The Persian version was finally committed to paper in a massive illustrated tome, probably in 1562, under the commission of the Mughal Emperor Akbar (about half of its remaining 100 pages are—of course—in the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum, the rest in Vienna). The Urdu version was printed in 1801, and translated much, much later by Musharraf Ali Farooqi in 2007.

It is a story many children in the sub continent are familiar with—the good bits are censored, of course, by concerned parents. And who can blame them? There is cannibalism (it’s not enough to kill a prisoner, some may want ‘kebabs of his heart and liver’ too), torture (threats of wives and children being pulverised in oil presses are no big deal), and of course, there are monsters galore. There is a two-headed lion, 60 cubits in length and a mighty beast (killed with one swing of Amir Hamza’s sword, never fear); a ferocious dragon that holds a castle between his jaws; violent, devious jinns; ghouls who bleed when they are cut, only for new creatures to emerge from the spilt blood; a creepy, multi-headed teenage boy who will not die until the end of time, whose heads fly right back and becomes reattached to his bodies when it is cut off; the deadly and powerful giant demon dev Ifrit, whose cut up body parts grow into full-sized Ifrits in a relentless cycle of death and re-birth. Many of the monsters found on screen courtesy of people like Ray Harryhausen, in movies including Hessler’s The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, seem to have come from this dastan. It’s practically a creature feature itself.

As many stories belonging to the dastan tradition are, The Adventures of Amir Hamza is deeply fatalistic. Much is predetermined for our hero, and we know this well before he even finds out about the prophecies that predict that he is the chosen one. As a baby, Amir Hamza is nursed for a week by a slew of supernatural and fearsome creatures—peris, jinns, devs, ghols, lions and panthers at the magical mountain of Qaf, a place he is destined to save as an adult. It’s interesting that many of these creatures are associated with evil and violence—lions and panthers in the most obvious, wild way, while ghol (ghul or ghouls) are demonic creatures, a sort of jinn living around burial grounds, and devs, too, are considered malicious. With such a fantastic mix of ‘other’ wet-nurses, there was no way Amir Hamza’s life was going to be anything other than a violent, magical adventure.

Amir Hamza is a strange hero. He isn’t always good, he very often doesn’t do the right thing and he’s really just very selfish. Still, he’s the hero we’ve got, and there is no doubt that he is the man the prophecies spoke of. We’re often told he’s immensely brave, outrageously strong and, of course, devastatingly handsome.

Amir Hamza’s looks get him far with the ladies, and true love features heavily in the dastan—why wouldn’t it? No swashbuckling ancient epic heroic adventure is complete without the love of a good woman—or several. Sometimes even at the same time. Amir Hamza’s one true love is the ‘apogee of elegance,’ the human princess Mehr-Nigar, before whose beauty ‘even the sun confesses its inferiority.’ Hamza promises her ‘until I have taken you as wife with betrothal, I shall never have eyes for another woman!’ but he isn’t at all true to his word. He’s persuaded quite easily to marry the princess Aasman Peri in Qaf (you see, their marriage is destined, he can not say no!) and he also has multiple trysts along the way to Qaf, quite easily and with no thought of poor Mehr-Nigar, who awaits his return.

We must not forget that regardless of the scary monsters, rampant sex, and copious drinking of wine, this is also a tale of Islamic mythology. Amir Hamza relies on his faith a great deal to help him fight evil, even converting many people to Islam as he goes along his adventures, including Mehr-Nigar and even a few villains who repent their ways when they hear of ‘the True Faith.’ Often, when faced with supernatural adversaries or challenges, Amir Hamza recites the name of the ‘One God’ to help him and is afraid of nothing because the ‘True Saviour’ is his protector. He says his prayers regularly too, and bellows ‘God is Great’ before charging off into battle so ‘powerfully that the entire expanse of the desert reverberated with the sound and the jinns very nearly died from fright.’

No ancient epic could be complete without plenty of bawdiness too—and The Adventures of Amir Hamza is a complete ancient epic in every respect. All the characters are very comfortable with their sexuality, there are orgies both with and without magical beings, plenty of ribaldry in the dialogue, some cross-dressing, and quite a bit of drunkenness—everyone really does seem to chug flagons of wine quite frequently and with great gusto. There is even a very strange tale of bestiality between a woman and her husband, a ‘horse resembling a wild bull’—a coupling that results in the birth of a rabid, feral colt.

It is worth mentioning that this dastan is not particularly kind to its female characters, but then it’s not really kind to anyone but Amir Hamza himself. There is rape and violence towards women but just as much as there is towards men—there are even pokes and jibes at misogyny. Of the female characters—and there are plenty—the two most interesting are Amir Hamza’s wife in Qaf, the lovely Aasman Peri, ‘unsurpassed in charm and beauty,’ princess of the realm of magical beings who inherits her father’s throne, and the formidable Maloona Jadu, the evil sorceress, mother of the deadly Ifrit who can create a magical and powerful tilism (an alternate universe). Maloona Jadu is complicated (think of her as an eastern Grendel’s mother) and Aasman Peri develops from a smitten young fairy-bride to a powerful, vengeful warrior scorned, a woman who ‘raged like a flame from the fury of her anger’ at being separated from Amir Hamza, so much so that when he tries to leave Qaf for the earthly realm, she marches with an army to lay waste to an entire city in order to take back the man she loves. It’s besides the point that he no longer wants to be with her (told you he’s a bit of a cad), but hey, Aasman Peri is mighty fierce nonetheless.

Amir Hamza is every hero my part of the world has every known. He is Rustam and Sikander and Sulaiman and Sinbad and Ali Baba. Comprised of history, folk legends, icons and religion, his dastan has informed much of Urdu storytelling. It’s a dazzling, confusing, enormous classic that deserves to be savoured and more importantly, deserves to continue being told all over the world.

A note on the translation: Four versions of The Adventures of Amir Hamza exist in Urdu. The version I’ve referenced was written in 1871, and translated by writer Musharraf Ali Farooqi, in what he told me was a long, difficult process: ‘I remember it took me a few weeks to translate the first couple of pages of the archaic text. It was my first attempt at translating a classical text. Also at that time I did not have as many dictionaries as I do now. So it was slow, painful going. The Urdu classical prose is unpunctuated so the decision of isolating sentences from strings of phrases is a subjective one.’

Mahvesh loves dystopian fiction & appropriately lives in Karachi, Pakistan. She reviews books & interviews writers on her weekly radio show and wastes much too much time on Twitter.