As it turns out, keeping the existence of a tiny, secret planet inhabited by squishy Mushroom People is not all that easy, especially if the person who discovered the planet was in correspondence with certain scholars, and in particular one Prewytt Brumblydge, who seems to be well on his way to creating a machine that can unravel the planet. (Spend a moment thinking about what you did this morning, and feel either smug or deeply unproductive in comparison.)

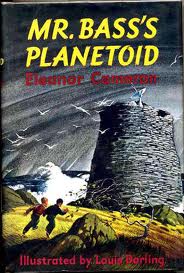

And, as it also turns out, David and Chuck, the protagonists of Eleanor Cameron’s two previous books, don’t have just one tiny, secret planet to protect. They have two: the Mushroom Planet, and Mr. Bass’s Planetoid.

But first, they have to deal with Mr. Brumblydge, a distinguished, if occasionally over-excitable scientist and friend of that great inventor and explorer Mr. Tyco Bass. Encouraged both by Mr. Bass and by a genuine desire to help the world, Mr. Brumblydge (total aside: this is just an awful name to type) has created a machine that in theory can easily and cheaply convert salt water into fresh water, allowing, as Mr. Brumblydge grandiloquently explains, the desert places of the world to bloom with food supplies. He fails to note that this will also ensure the extinction of various desert critters, but, you know, humans first, as this book likes to emphasize.

Unfortunately, not only does the machine have the potential ability to unravel Earth and destroy oceans, which sounds kinda awful, but also, it can only be fueled by a heavy metal that Mr. Brumblydge calls—let’s all applaud the egotism here—Brumblium. At the moment, only two grains of Brumblium can be found on Earth—one in Mr. Brumblydge’s possession, and the other in the home of Mr. Bass—which is one reason why Mr. Brumblydge has arrived at the house, now used by David and Chuck to study science and, from time to time, work on building a spaceship. Alas, shortly after this visit, Mr. Brumblydge (AUUGH, this is just an awful name to type) vanishes, for the second time in this book, to the distress of the boys and a couple of detectives wanting to hunt him down. Because David and Chuck know the source of Brumblium—the Mushroom Planet they have chosen to protect. And they can’t let it be mined.

Total aside: From a sheer writing perspective, you have to admire the rather neat trick Eleanor Cameron pulls off in this book: turning a scientific criticism of her earlier books (how does the air stay on the Mushroom Planet?) into a plot point for this book. Granted, the solution raises about as many questions as it answers, but it’s still clever.

Anyway. The boys realize that they have to find Mr. Brumblydge, and really, the only way they can accomplish this is by taking their satellite up to Lepton, the other planetoid discovered by Mr. Tyco Bass, and look for Mr. Brumbly….Look, I give up. I’m calling him Mr. Brum for the rest of the post. This of course involves repairing the space ship with the help of Chuck’s grandfather. But without the genius of Mr. Tyco Bass, the spaceship isn’t quite perfect.

Also, if I may note, the entire plan seems unnecessarily complicated. After all, the kids have a high-speed spaceship. Why not use that to speed round and round the world, looking for Mr. Brum, instead of having to get detailed instructions of how to land their tiny spaceship on to a planetoid the size of a city block?

Anyway, after several frantic signals and calculations that will make many readers today feel renewed thankfulness for their GPS devices, the boys find Mr. Brum at last—in a small island in the Scottish Hebrides. Which isn’t quite the end of the story.

Like its predecessors, this is a fast paced, action filled adventure. But unlike its predecessors, the plot just seems unnecessarily complicated—not just the plan to head to a tiny planetoid to search for someone on Earth instead of, I don’t know, staying on Earth and searching, but also the multiple communications back and forth between Earth and the Mushroom Planet to let the boys do all this; the way Mr. Brum starts out disappearing, then appears, then disappears, then appears, then…I think you can guess. It makes it very hard for me to worry about the disappearance of a character when said character has already reappeared three times in what is a very short book.

The ethics here are also—how can I put this—not completely thought through. Both boys decide that it would be wrong to sacrifice the Mushroom Planet and turn it into a mining operation to service the human need for water, but as I noted, not only have a grand total of zero people thought about the impact on desert life, once again, two boys are making decisions on behalf of the Mushroom Planet without consulting any of its residents. Given that in the last book we learned that many of the inhabitants of the Mushroom Planet are quite capable of caring for themselves and have access to divine wisdom and secret potions that can act as memory wipes, this seems particularly wrong. But what’s really wrong: despite agreeing that mining the Mushroom Planet is wrong, the end of the book celebrates the fact that this machine actually works, even though it can only work by mining the Mushroom Planet.

It’s a mixed message, and rather odd for the Mushroom Planet books, which until now have had the fairly clear message of “Do the right thing,” not “Celebrate the invention of something that will force you to do the wrong thing.” I haven’t always agreed with what Cameron thinks the right thing is, but the books have been consistent on this, and it’s an odd change—especially since her characters seem disinclined to consider the issues they were just considering chapters earlier.

And I also remain mildly surprised that the only real objection made by David’s parents to the idea that he should fly a spaceship up to a tiny planetoid to spy on people is that he shouldn’t do it for very long. Like, twelve hours, tops, and he should be sure to take naps.

And two parts of the work have really not dated well. First, Eleanor Cameron’s attempt to visualize what the planet would look like from orbit. She wasn’t completely wrong, but she was wrong enough for a woman writing right after the Sputnik launch, who must have been aware that color photographs were about to come next. Reading this after having seen pictures taken from the International Space Station and the Moon is slightly jarring. Also, Mrs. Topman, one of the so far two females (one girl, one woman) with a speaking part in any of the books, but otherwise mostly a non-entity, is continually ignored and overruled in this book: apart from making a few meals, most of which go uneaten, her other role is to say that she knows where women hide things, but has no idea where Mr. Bass would hide things. Well, that’s helpful.

If you’ve already read along in the Mushroom Planet books, I’d say continue, but this is probably not the best book of the series to start with—even with the last few paragraphs teasing a sequel.

Said sequel, however, A Mystery for Mr. Bass, is nowhere to be found in the local county library, was not found (yet) on interlibrary loan, and only to be found on the internet for the low, low price of $150 (for a book cheerfully and frankly listed as “in poor condition”) and up. At that, it’s cheaper than what Barnes and Noble currently lists as the price for this book—$160. After about fifteen seconds of contemplation I realized that I didn’t want to read the book that much, much less try to convince the powers that be at this site that they should reimburse me for this, so we’ll be jumping on to the next book, Time and Mr. Bass.

Mari Ness now wants a little planetoid of her own to orbit the Earth with. Meanwhile, she lives in central Florida.