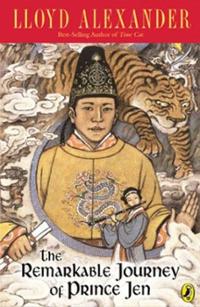

Writing about paragons can grow wearisome after awhile, even if you are Lloyd Alexander, gifted with the ability to come up with ever more implausible plot lines for your heroine. So, after a long period with Vesper Holly, Alexander turned his attention to something new: a novel about a young hero who is most definitely not a paragon.

Oh, Prince Jen means well, certainly, but as a young, pampered prince, he has been very sheltered from the realities of life, and he is in no way prepared mentally or otherwise for a journey, even a remarkable one. But when a wise man shows up at his doorstep with a tale of a fabulous kingdom of happiness, T’ien-kuo, he is determined to visit, starting The Remarkable Journey of Prince Jen.

On the advice of the wise man, Master Wu, Prince Jen takes six treasures from the imperial treasuries with him to give as gifts to the king of this fabulous kingdom. Not objects of gold, but an iron sword, a leather saddle, a wooden flute, a bronze bowl, a sandalwood box, and a kite. A few people object to the kite, but I have to say, if you are trying to cheer people up and convince them you are trustworthy, nothing better than a kite. That does not turn out to be the reason for including the kite, but I anticipate.

As Jen travels, he encounters various wise and not so wise elderly men, bandits, a thief who has some rather restricted rules on thievery, a flute girl, and constant reminders that he knows virtually nothing about real life, laws or his own kingdom. He also finds himself surrendering or giving away every one of the six items he meant to give to the king. As he does, it becomes clear just why Master Wu thought the seemingly ordinary items would make good gifts: all six are magical. But Jen has other things to worry about besides magical kites: a bandit is threatening to take over his father’s kingdom (thanks, in part, to that iron sword); his friends have vanished, and he himself is in frequent danger of losing his head. Plus he has the whole difficulty of finding this marvelous kingdom that he’s trying to reach, given that his guides are not always the most reliable sort.

Let’s just get my major complaint out of the way here immediately: somebody, either Alexander himself or an editor, decided to end every. single. chapter with a little summary in italic font of where the characters are and what will be happening in the next chapter, like this:

Our young hero is eager to start his journey, but Master Wu seems to be casting a dark shadow on a bright prospect. What can be the difficulty? To find out, read the next chapter.

Prince Jen’s praiseworthy attempt has only put him in danger of being drowned. The outcome is told in the next chapter.

Has our hero begun to develop some affection for a flute girl? A more urgent question: What has become of Li Kwang and his warriors? The answer is given in the next chapter.

AND SO ON AND SO ON through the book. Annoying doesn’t begin to cut it.

I don’t know who was responsible for this narrative irritation: the tone somewhat sounds like Lloyd Alexander at times, but whatever else can be said about Alexander, he always respected his young readers, trusting that they were capable of dealing with hard truths and figuring things out on their own. And one or two other errors—mistaken names and so on—suggest that Alexander’s editors weren’t taking their usual care with this book. Or maybe they were just spending too much time on these end of chapter things.

The only possible justifications I can think of is that a) Alexander wanted to experiment a bit, or b) some editor somewhere decided that parents reading the book out loud to small children would need some narrative help. If the second, I’m mildly insulted on behalf of all parents—my mother was perfectly capable of pretending that she didn’t know what would happen next and saying, “Oooh, what an exciting place to stop! You need to go to sleep NOW. No, we are not reading anymore. BED. NOW.” And I was perfectly capable of sneaking off and finding out what happened next all on my own when it was obvious that I couldn’t wait until our next Story Time.

….let’s pretend I didn’t just publicly admit to doing that and move on, shall we?

Let’s also mention the second issue, which is that pretty much every character in the book is a retread of characters from Alexander’s previous books: Voyaging Moon, the flute girl, is the standard brave and talented love interest; Mafoo the standard comical servant; Moxa, the standard good hearted thief, and so on. The dialogue, too, is strongly reminiscent of previous books, although if you love Alexander—and by now it should be clear that I do—you’ll find this a good thing.

And, of course, the novel uses what was by now an almost default setting for Alexander: a narrative continually interrupted by various short stories, often of other people. In the case of this book, some of these stories – especially the tale of the girl and the kite – are actually more enthralling than the main narrative, but that might be because the main narrative is constantly getting interrupted. This was a storytelling format that Alexander clearly loved, but although it mostly works here, that plus the freaking chapter endings makes it rather difficult to get involved with the storyline.

Which is not to say that the book has nothing new. The main thing, of course, is the setting, new for Alexander, one very loosely based on early medieval China. Alexander noted that the six items in the story were more or less based on his memories of some of the items his father collected in his import-export business. (He would also use these memories in a later book, The Gawgon and The Boy.) Alexander also draws from some Chinese fairy tales to tell his tale. But although the novel is sort of set in a mythical China, like Prydain, this is very much a country of Alexander’s own imagination, inspired by, not accurate about, the original, and does not feel particularly tied to or strongly close to the original.

And what does work, very well, are some of those interspersed tales. My favorite is undoubtedly the one with the little girl and the kite that allows her to fly (I desperately need a kite like that) but I also loved the story about the sandalwood box, which turns out to have some very magical ink indeed. (In related news, I also desperately need a box of brushes and inks that turn into whatever colors I can imagine and allow me to step into the paintings I create and talk to tigers.) I also liked the way Alexander worked with just how the gifts were obtained: the stolen ones caused grief, the ones given away brought joy, but neither the grief nor the joy comes quite as expected.

Despite that, I can’t list this as one of Alexander’s better books, largely because of those AUUUGH chapter endings that had me ready to throw the book across the room by the end. But I can recommend this to Alexander fans looking for a little bit more magic.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.