Welcome back to the British Genre Fiction Focus, Tor.com’s regular round-up of book news from the United Kingdom’s thriving speculative fiction industry.

This week, we lost Doris Lessing.

“That epicist of the female experience, who with scepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilisation to scrutiny,” passed away in her London home on Sunday, so there’s only the one way for us to start today: with a taking of the tributes that have been rolling in in honour of the Nobel Prize for Literature winner since.

Later on, in Cover Art Corner, Tor UK have been toying with two designs for Ben Peek’s debut, Immolation, and it’s up to us to decide which one makes the cut.

The Death of Doris Lessing

Born in 1919 to a pair of English parents, Doris Lessing spent the first few years of what was a wonderful and very varied life in Persia (now Iran) where her father was employed as a banker. In 1925 she and her family were uprooted to move to the British colony of Southern Rhodesia—Zimbabwe to you and I—the better for her father to make his fortune farming a thousand acres of maize.

This went just about as well as could be expected: the farm fell flat. Duly disillusioned, Lessing left school at age 14, and left home at age 15. That also so happened to be the year she sold her first short stories to a miscellany of magazines in South Africa—from which country the government later banned her because she dared to campaign against apartheid—beginning a career that occupied her for a period of nearly 80 years.

Her commitment to fiction was phenomenal, but her efforts to make the world a better and fairer place were truly tireless, too.

Her first novel, The Grass is Singing, was published in 1950, resulting in something of a sensation, but it was with The Golden Notebook in 1962 that people started paying attention. When in 2007 she was finally awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, the year before the publication of what we must now call her final novel—namely Alfred and Emily—Lessing used her legendary acceptance lecture to draw attention to the inequality of opportunity. A limited edition of the text of her lecture was later published to raise money for children living with HIV/AIDS.

Sadly, Doris Lessing died in the early hours of Sunday morning. She was 94 years old.

Without her, the world—never mind the British genre fiction industry for a moment—is not what it was. It’s less. It’s bereft.

In the words of Margaret Atwood:

As we age, we face a choice of caricatures; for women writers vis à vis younger ones, it’s Cruella de Vil versus Glinda the Good. I encountered my share of Cruellas along the way, but Doris Lessing was one of the Glindas. In that respect, she was an estimable model. And she was a model also for every writer coming from the back of beyond, demonstrating – as she so signally did – that you can be a nobody from nowhere, but, with talent, courage, perseverance through hard times, and a dollop of luck, you can scale the topmost story heights.

And Doris Lessing indubitably did. I’ve only read a few of her books—Martha Quest, The Fifth Child and of course, The Golden Notebook—but I was left stunned by every one.

Nicolas Person, Lessing’s editor at Fourth Estate—which is to say the HarperCollins imprint which has had the pleasure of publishing her work in recent years—called her career “a great gift” to the literary industry:

“She wrote across a variety of genres and made an enormous cultural impact. Probably she’ll be most remembered for The Golden Notebook which became a handbook to a whole generation, but her many books have spoken to us in so many various ways. […] Even in very old age she was always intellectually restless, reinventing herself, curious about the changing world around us, always completely inspirational. We’ll miss her hugely.”

What follows are the thoughts of fellow novelist Justin Cartwright:

She was truly unique in her views and in her take on life. In my youth I had been a devoted reader of her early books, perhaps the first five, or six, up until The Good Terrorist. But her experimental science fiction ended my devotion. I thought there was a degree of whimsy in her later work, a kind of unedited rush of words that I simply could not read. But I never underestimated the depth of her concerns, about women, about literature, about injustice, and about the fate of Zimbabwe. When she offered two books to publishers using the name Jane Somers, she was making a very valid point about the difficulties facing women writers.

And then some time later I read the wonderful Martha Quest, and soon after that her autobiography. There is a passage in the first volume of her memoir that is the most devastating account, coldly brilliant, I have ever read of parents as seen by a child: “I walk up out of the bush… and stop when I see my parents sitting side by side, in two chairs, in front of the house… I see them both very clearly, but from a child’s view, two old people, grey and tired. They are not yet fifty. Both of these people are anxious, tense, full of worry, almost certainly about money. They sit in clouds of cigarette smoke and they draw in smoke and let it out slowly as if every breath is narcotic. There they are, together, stuck together, held by their poverty and – much worse – secret and inadmissible needs that come from deep in their two so different histories. They seem to me intolerable, pathetic, unbearable, it is their helplessness that I can’t bear. I stand there a fierce unforgiving adamant child saying to myself… I will not be like that.”

The adamant child became the adamant adult. She truly had ice in her veins. She believed that her insight and her talent were unique, and she may well have been right.

I think she was, obviously.

I hate that it’s taken Lessing’s death for me to do this, but I’ve just bought copies of the five-volume Canopus in Argos: Archive, a celebrated sequence of science fiction novels published between 1979 and 1983, and I mean to start reading them this week.

But let’s conclude with a few words from The Telegraph’s boss of books, Gaby Wood, who wrote about what Lessing did for women:

Lessing wrote about women’s ambivalence about motherhood and sex and work in a way that was simultaneously shocking and influential. If she rejected the feminist label it was perhaps because she had no need for it. If others gave it to her it was perhaps because they needed her. It’s often said that what we think of as the Fifties and Sixties are more cultural concepts than chronological ones, and that the Sixties as we now think of them didn’t begin until well into that decade.

The Golden Notebook, which was published in 1962—in other words, the Fifties—was not only ahead of its time but a blueprint for women in times to come. As Lessing herself put it, it was written “as though the attitudes that have been created by the Women’s Liberation movements already existed”.

Lessing was able to do a great deal for women without subscribing to feminism; she did it with her life, and with (not just within) her writing.

Cover Art Corner: Choose Your Own Cover Art Adventure

Fact: we talk a lot of smack about cover art.

For good reason, too—or rather reasons. Originality is rare—the hooded dude, for instance, has become a sort of shorthand for fantasy fiction—and in technical terms the amateurish execution of altogether too many contemporary covers reminds me of my first fool-arounds in Photoshop. Not to touch on the topic of whitewashing…

It’s what inside that counts, of course. But let me underscore that cover art is important. If not for dedicated genre fiction fans who will read the next Alan Campbell (for example) without the slightest concern about what’s on the cover, then for window shoppers who’re looking for an interesting new book. Perhaps a dashing man with a bow and arrow will draw them in inasmuch as it puts us off, or vice versa.

One way or the other, the artists and designers behind the cover art we tend to either revere or revile are serving many masters, and it must be almost impossible to please every party. As Julie Crisp, Editorial Director of Tor UK, reminds us, “creating covers is hard.”

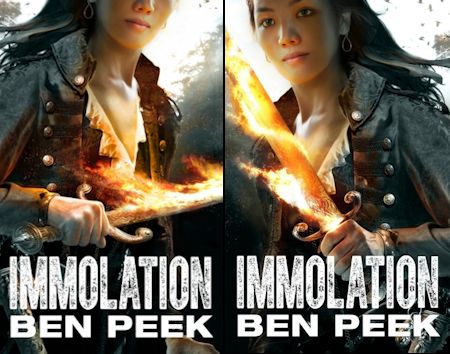

To her credit, however, she’s suggested a sort of compromise. By the point at which we see a cover, nine times out of ten it’s done and dusted. No changes can be made. But that’s not the case today. Not with Immolation:

I always quietly (or maybe not so quietly) seethe when I see comments on the internet claiming that publishers just ‘throw’ an image on the front of a book. Actually a lot of time is spent briefing, going over roughs and then discussing (read intense debate) what we think will work for everyone.

And sometimes it reaches a stage of discussion when I just think, why don’t we ask the readers? So I am. Here you go.

In August next year we are publishing the AWESOME Ben Peek’s debut novel, currently called Immolation (and yes, there are also even discussions about the title!). You can see the press release here. It’s an epic fantasy told through three perspectives – one of whom is a young woman.

So my brief was, there are three books and three characters. Let’s try and get one of the characters on each of the books starting with Ayae because – well – because she’s really cool!! And she sets her sword on fire. And she’s a woman. And I like her. That was pretty much my thinking. And we’ve come up with a direction that everyone likes but we can’t actually decide on which one works best! Now, before I show you, let me reiterate that these are what we call visual roughs. There’s still a fair amount of work to be done on them. But I want your opinion on the crop, pose and figure – and hell, the title while you’re at it! :-)

For my part, I like the title. And as to the two covers, the first is my favourite. Showcasing the model’s face in the second makes Immolation seem straight-forward. The first leaves a little to my imagination, which I really appreciate.

Here’s an early look at the book, if it helps your thought process at all.

Immolation is set fifteen thousand years after the War of the Gods. The bodies of the gods now lie across the world, slowly dying as men and women awake with strange powers that are derived from their bodies. Ayae, a young cartographer’s apprentice, is attacked and discovers she cannot be harmed by fire. Her new power makes her a target for an army that is marching on her home.

With the help of the immortal Zaifyr, she is taught the awful history of ‘cursed’ men and women, coming to grips with her new powers and the enemies they make. Meanwhile, the saboteur Bueralan infiltrates the army that is approaching her home to learn its terrible secret.

Split between the three points of view, Immolation’s narrative reaches its conclusion during an epic siege, where Ayae, Zaifyr and Bueralan are forced not just into conflict with those invading, but with those inside the city who wish to do them harm.

Sounds interesting, yes? So let’s band together and make sure Immolation launches with a good look. Remember that you can’t complain about the sorry state of affairs of cover art today if you’re not prepared to have your say.

Talk to you all again next time!

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.