I love Sleepy Hollow. You should too. We’ve provided ample reasons why already. I love basically everything it’s doing. That being said, I come today bearing warning, not praise! Sleepy Hollow is well-written, it has interesting things to say, but it will lead you astray if you let it. Like that great series of movies which I believe inspired this masterpiece of a show, National Treasure and National Treasure 2: Book of Secrets, Sleepy Hollow overflows with a burning love of history that is almost entirely lacking in factual accuracy. So, in the name of greater enlightenment, I have compiled a list of things you shouldn’t learn from Sleepy Hollow.

1) The fate of the world was at stake in the Revolutionary War

Sleepy Hollow’s stakes are huge. End of the world huge, the apocalypse is coming and we need to be ready for the Horsemen huge, we are being stalked by a powerful demon who can turn the very forces of huge. Abbie Mills and Ichabod Crane are fighting a battle that’s been raging for centuries, a conflict that has warped history by dictating the course of the Revolutionary War, an exciting and important geopolitical conflict. Ichabod Crane was constantly being sent on missions of utmost occult importance by his good friend General George Washington, a connection that is both adorable and critical to the construction of most of the episodes’ plots.

It makes perfect sense for an American show to care this much about the Revolutionary War. It’s our war! We won it and that’s how we got to be a nation, hurrah! In terms of its geopolitical impact, however, the Revolutionary War pales in comparison to the Seven Years War, which preceded it, and the Napoleonic Wars that came after. In fact, the largest military action in the Revolutionary War didn’t even happen in the New World. 1779’s Great Siege of Gibraltar, in which the Spanish and French tried to capture the heavily defended Gibraltar, involved a staggering 70,000 troops. Basically, Sleepy Hollow would have you believe that the important point of contention in the war was the specific, local resources afforded by the colonies, whether those resources are tobacco or fonts of demonic power, and that’s misleading at best.

2) The war was fought over a 2% tax on tea.

Ichabod Crane struggles with adapting to many things in the modern world. His first shower was a terrifying experience, his first light switch a mystifying one, and he’s yet to meet a motorized vehicle that he can enter or escape from without the help of Abbie (or, on one occasion, Yolanda.) Our era has given him some sweeter surprises as well! Much loving fanart has been dedicated to Ichabod’s instant delight upon eating a doughnut hole. Before he could achieve that bliss, though, Crane had to overcome his outrage at discovering New York State sales tax. A 10% tax on baked goods? Impossible! Tyrannical! He reaffirms his revolutionary spirit immediately, reminding Abbie that her nation was founded as a result of a tax of merely 2%. That tax rate is understandably shocking to Crane, given his background. Setting aside any pro- or anti-tax sentiments any humans may or may not feel, however, I have a question. Where is that number coming from, exactly?

Britain imposed a number of different taxes on its colonies leading up to the war. The first, and perhaps the most germane to our delicious doughy treat, was the Sugar Act of April 5, 1764. How much did it raise tax rates on sugar? Actually, it cut a previous tax of 6 pence per gallon of molasses in half, in exchange for greatly strengthening the ability of local forces to collect the previous uncollectable levy. This is a flat amount tax, rather than anything that could be construed as a percentage of the cost of a purchase. The Stamp Act of 1764, in contrast, did scale based on what was being bought, but it would be hard to describe it as a 2% tax either. It was more of a collection of different fees. Both of these acts were repealed in 1766.

The Townshend Acts were far more proximal to the revolution, being the first set of acts that levied a tax on goods that the colonies had to import. So, was it a 2% tax? I’m afraid my best answer is “maybe.” The writers of that bill got deep into the nitty-gritty of what they would charge on which items, and it’s frankly bewildering to behold.

What we can take away from all this: tax was a driving cause of the Revolutionary War, but it probably wasn’t a 2% tax. Also, tax codes have always been weird, and now I have a headache. Moving right along…

3) The Boston Tea Party was a cover-up!

Okay, so let me get this straight, Sleepy Hollow. Tax is super important and bad, and Crane will hate it forever. But also, the Boston Tea Party, as we so festively call it, was just a big cover-up so Crane could go steal a magic sextant projector doohickey. Apparently you can have it both ways!

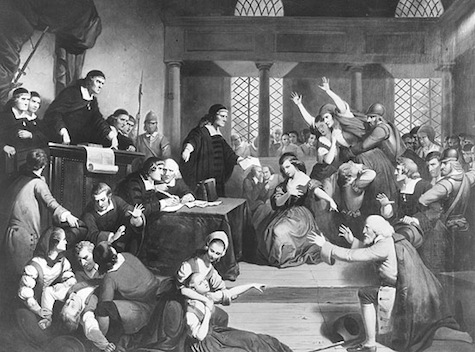

4) Everybody loved burning witches in New England

Katrina faked her death by burning. Saralda of Abaddon was actually burnt at the stake. Crane leads Abbie to catacombs filled with hundreds more skeletons of crispy-fried witchbones. Since the woman who is arguably Ichabod Crane’s most important emotional connection (but it sure is an ongoing argument, guys) is a self-professed witch, and since America has an uncomfortably problematic historical habit of executing “witches” wholesale, you can expect witch burning to be a recurring theme on Sleepy Hollow.

In a world where witchcraft is a real thing, rather than a superstition or ongoing collective psychosis, I can see persecution of witches being expanded and prolonged. However, the real world has two points of divergence from Sleepy Hollow re: witches. First, witches were never burnt in the British Colonies. All victims of the Salem witch trials were either executed by hanging or pressing. Second, and perhaps more importantly, there were zero recorded convictions of witchcraft in the colonies after Salem, a full 80 years before the days of Ichatrina. But that’s not the last outmoded practice Sleepy Hollow employed.

5) This child from Roanoke is speaking Middle English

The fact that Ichabod Crane speaks fluent Middle English is entirely seductive, and I will never throw shade at anyone who conspires to reveal that speech to us. It’s also completely justifiable for him to speak the language of Chaucer, as a polyglot polymath professor of Merton College. The people of Roanoke have no such justification.

The Lost Colony of Roanoke was established in 1585, and Lost some time after that. Hundreds of years later, a popular but confusing documentary about it surfaced, but that’s beside the point. What matters is that in 1585 no one spoke Middle English. No one had spoken anything that could be classified as Middle English in decades. England was solidly ensconced in the Early Modern period, the period of Shakespeare, the bard who began writing plays in somewhat antiquated but still recognizably modern English just a few years later. I invite you to compare a few lines from Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida (c. 1602) and from Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde (c. mid 1380s). There’s kind of a difference:

In Troy, there lies the scene. From isles of Greece

The princes orgulous, their high blood chafed,

Have to the port of Athens sent their ships,

Fraught with the ministers and instruments

Of cruel war: sixty and nine, that wore

Their crownets regal, from the Athenian bay

Put forth toward Phrygia; and their vow is made

To ransack Troy, within whose strong immures

The ravish’d Helen, Menelaus’ queen,

With wanton Paris sleeps; and that’s the quarrel.Troilus and Cressida, Act I, Prologue, Lines 1-10

The double sorwe of Troilus to tellen,

That was the king Priamus sone of Troye,

In lovinge, how his aventures fellen

Fro wo to wele, and after out of Ioye,

My purpos is, er that I parte fro ye.

Thesiphone, thou help me for tendyte

Thise woful vers, that wepen as I wryte!Troilus and Cirseyde, Book I, Lines 1-7

6) No one knows what happened to Roanoke…

I mean, we don’t know for sure, but there are a lot of pretty good theories on that subject these days. Plague is, actually, one of the culprits. And it’s cool how they ended up getting magically transported up to upstate New York in order to teach Abbie a lesson in faith and all that. But, uh… Why would Ichabod believe that they actually hiked up there? It’s 600 miles from Roanoke Island to Sleepy Hollow, along a route that required access to a bunch of bridges that totally didn’t exist back then, and those guys were perilously unwell.

Anyway, the “mystery” of Roanoke has a leading explanation right now. There’s some evidence that the colonists interbred with local indigenous peoples and abandoned their terrible little colony. I can’t fault Crane for not knowing that, since his intel is hundreds of years out of date, but I can urge you not to repeat his mistakes.

7) Almost anything about the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) people

My tagline for this was going to be that there’s no way scorpions could possibly be a traditional component of any rituals performed by this group of people originally native to New York, but then I started researching scorpions and realized that they can live almost anywhere. They probably still aren’t very common along the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers, but my ability to determine that fact for certain has taken a backseat to gibbering terror.

Episode Three, “For the Triumph of Evil,” made what I think was a valiant attempt to expand the series’ diversity-minded efforts to Native Americans, and Michael Teh’s performance as Seamus Duncan was very good and self-aware, but in almost every application of fact the episode falls short. The depiction of the ritual is extremely unlikely, even if you put aside the evil death scorpions, because jasmine and cherry root, two of the three ingredients in the dream-inducing tea, are old world imports. Ro’kenhronteyes is totally made up—unlike Moloch or the Headless Horseman. The most glaring misinformation, though, is that Crane had an extensive acquaintance with Mohawk trackers and spies who assisted him in his Revolutionary Warrior capacity. Sorry, show, the Mohawks fought alongside the British in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.

From these various unfacts and misinformations, I think it’s safe to say that Sleepy Hollow is a delightful but completely unreliable source of historical information. It is perhaps a better guide to the fact that history exists than to any particular piece of knowledge. There is great value to be had in guiding people towards the knowledge that there is history out there, somewhere, and I trust Sleepy Hollow to do so.

Carl Engle-Laird is covered in scorpions. He wishes he were not covered in scorpions. He is also an editorial assistant, Way of Kings re-reader, and Stormlight Archive correspondent for Tor.com. You can follow him on Twitter here.